A (usually) biweekly series, The Ursula K. Le Guin Reread explores anew the transformative writing, exciting worlds, and radical stories that changed countless lives. This week we’ll be covering Rocannon’s World, first published by Ace Books in 1966. My edition is part of a three-book collection Nelson Doubleday, 1978, and this installment of the reread covers the entire novel.

We’ve visited anarchist utopias and lush worlds of excrement and excess, traveled together across ice and political turmoil, gone to the ends of the earth in search of ourselves, into the dark depths beneath the world and even into the afterlife itself. And we came back. We might not be the same as when we started, but here we are. What’s more, we did it all as a new coronavirus emerged and shut us away to work from home. I commend you all for making it this far, yet we’ve only just begun! Now we pass out of the shadow of Ursula K. Le Guin’s most beloved and influential works; now we head into stranger, older lands and start at the beginning.

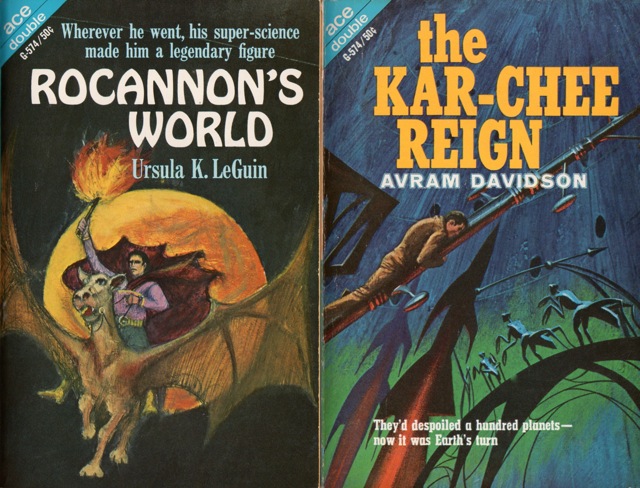

Today we come to Rocannon’s World, Le Guin’s first novel. It appeared in the Ace double tête-bêche format in 1966 alongside Avram Davidson’s The Kar-Chee Reign, an environmentalist allegory set in a distant future at the twilight of humanity’s time on earth. This wasn’t an especially auspicious beginning to Le Guin’s career, as Ace doubles were published with considerable regularity throughout the 1950s and 1960s and featured just about any SF author capable of stringing together somewhere between 20,000 and 40,000 words in the shape of a vaguely interesting plot. Of course, this included authors like Andre Norton, Philip K. Dick, Brian Aldiss, John Brunner, and others whose work would significantly influence the 1960s New Wave, but the Ace double roster also included many whose names are virtually unknown today. Like the pulps before them, Ace doubles were exciting, lurid, and published with occasional regularity, often fix-ups of successful short stories.

This is important context for Rocannon’s World, because although today the novel has been shinily repackaged (either in the poetically titled Worlds of Exile and Illusion or in a Library of America collection) and compared to the literary masterworks of The Left Hand of Darkness and The Dispossessed, it is a strikingly different sort of book, utterly at home with the mainstream of science fiction in the 1960s and quite unlike the Le Guin we’ve read so far.

Rocannon’s World begins with a prologue—actually a short story, or part of one, published as “The Dowry of Angyar” in the September 1964 issues of Amazing Stories. It was Le Guin’s eighth story. It tells of Semley, the most beautiful blonde-haired, dark-skinned royal lady of a planet called Fomalhaut II by the League of All Worlds, and how she ventures from her castle to her childhood home in the valley of short, happy folks, to the caves of technologically advanced short folk, and onto a great metal ship across the void between the stars, to a city at the end of night, where she at last recovers her family heirloom. In tragic fashion, she returns to her castle to find her husband dead and her daughter grown, and she goes mad.

The prologue might very well be the best part of Rocannon’s World, not only for the stylistic flair that is characteristic of Le Guin’s writing in the Earthsea Saga, but also because it deftly blends elements that seem to belong to fantasy into a world that we, as readers, come quickly to recognize as science fiction. Generic play between fantasy and SF was common in the 1960s and 1970s, of course, as a new generation of authors experimented with old attitudes and wondered how the perceptions of genre could be shifted by a few careful placed (or purposely left out) descriptors (think Lord of Light or Dragonflight). The prologue is a science fiction journey to another planet rendered in the language of medievalist fantasy (with coy nods to Wagner and Tolkien), and it excels incredibly at what it does.

The prologue, however, sets a high bar for Rocannon’s World. The novel that ensues takes place some years after Semley’s venture off Fomalhaut II, though that journey shaped the world’s fate without Semley, her progeny, or the Clayfolk who took her on the metal ship ever learning why. The reason? Rocannon, an ethnologist (i.e. anthropologist) of the High Intelligence Life Forms of the League of All Worlds, the predecessor to the Ekumen that will later dominate Le Guin’s Hainish cycle. After meeting Semley on her journey to New South Georgia where her necklace, Eye of the Sea, is kept in a League museum, Rocannon becomes curious about the League’s dealings with the intelligent species of Fomalhaut II (of which there are five). He learns that the League selected the Clayfolk/Gdemiar (akin to the dwarves of Tolkienian fantasy) for technological advancement in the hopes that they will be able to aid in the League in the ominously named War to Come. Rocannon puts a halt to League interaction with the planet and leads an ethnographic team to Fomalhaut II. Because of the time differentials involved in space travel, Rocannon’s expedition takes place nearly 5 decades after Semley’s return to her planet, though for Rocannon only a handful of years have passed.

The novel formally begins with the end of Rocannon’s expedition—a disastrous end! Rocannon and Mogien, lord of Hallan and grandson of Semley, discover the former’s ship destroyed in a nuclear blast, his shipmates dead, their survey data gone. Believing himself alone on a planet barely out of the Bronze Age and hardly known to the rest of space-faring humankind, Rocannon must discover who has attacked and get word to the League. One problem: he has no means of contacting the League; no spaceship to travel the eight-year distance to the nearest League planet, no ansible to communicate instantaneously with League representatives. A conundrum perfect for any good science fiction adventure.

And that’s just what Rocannon’s World is: a good, if relatively mediocre, science fiction adventure and very little else. I like to think of Rocannon’s World, this first novel of an author who only started publishing professionally 5 years earlier, as something of a prologue to the Hainish cycle. It is short, plot-driven, uninterested in character, and not particularly concerned with many of the things that Hainish tales will later take up, for example how the circumstances of life on different planets change the social, cultural, and even physiological meanings of humankind. If the Hainish novels and stories can be said broadly to be a sandbox for thinking about science-fictional extrapolations through the lens of anthropology, Rocannon’s World has only just begun down that path.

Buy the Book

The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue

What’s more, because Fomalhaut II is a planet of swordsmen, gryphons, castles, and many morphologically variant races of humans, the fantasy aesthetic gestures quite a bit to Earthsea, especially in Le Guin’s emphasis on myth as history. The world of Rocannon’s World is simple and it just so happens that the stories of old, the legends and myths, lead exactly where they say they will: to cities of monstrous bird people, to a race of gorgeous fair-haired progenitors of the anthropomorphic people, to a species of intelligent rodents, and to mythical dwellers-in-mountains who give Rocannon the gift of telepathy. Things are as they seem; all one needs to achieve the end of a great quest is courage and a willingness to sacrifice.

But I don’t want to completely dismiss Rocannon’s World, even if in the end it can be summarized easily enough as “good vivid fun . . . short, briskly told, inventive and literate” (perhaps the only thing I agree with Robert Silverberg about). It is a novel that demonstrates an author struggling to come to terms both with the market she writes for—a market that, by and large, ate up the sort of “good vivid fun” Rocannon’s World exemplified, and that was characterized by many of the novel’s traits, especially its focus on a plot that drives through a scenic tour of a strange SFF world with little interest in the how and why, or the development of the who—and cutting a trail for wider, more sophisticated craft to emerge. Though only a few years apart, Rocannon’s World and The Left Hand of Darkness seem to have been written by completely different people.

Here, I think the concept of Rocannon’s World as a prologue to the Hainish cycle, an unfinished chapter, an old legend of a not-yet-fully-imagined storyworld, is an effective way to think of the novel. Certainly, it deals with grand ideas of loss and sacrifice, with Rocannon losing both his friend Mogien and his attachment to his people, his ability to return home, in exchange for the telepathic powers that allow him to defeat the rebels who threaten the League. Moreover, we glimpse the fascinating history of the Hainish cycle, see the Cold War that the League of All Nations is preparing for against an unknown Enemy, and glimpse the imperial uses of anthropological knowledge (ethnological surveys) and minority populations (the Clayfolk) in the effort to bolster the League’s position in a future war that hardly concerns the people of Fomalhaut II. Rocannon’s World is almost a science fiction novel of ideas, but it would seem that it was not the time or place for it to become one—whether that’s because Le Guin wasn’t there yet, or because the publishers weren’t, is moot since all of this was rapidly changing in the 1960s as the New Wave crashed in from Britain, took over the U.S. genre market, and pushed Le Guin, Joanna Russ, Samuel Delany, and so many others to dazzlingly heights of artistic accomplishment.

Rocannon’s World is a fun, short, easy read, but nonetheless an adventurous and worthwhile part of the legacy Le Guin left to us. So, too, is our next novel, Le Guin’s second and also one set in the Hainish cycle: Planet of Exile. There, we’ll see the Hainish themes of exile, exploration, and the ethics of League/Ekumen governance develop further. Join me, then, next week on Wednesday, June 17 as we venture to planet Werel. Stay safe and keep the power. Be seeing you!

Sean Guynes is a critic, writer, and editor currently working on a book about how the Korean War changed American science fiction. For politics, publishing, and SFF content, follow him on Twitter @saguynes.

I remember finding Roccanon’s world enjoyable enough but strictly ok, but the short story of the prologue (which I had read before, separately, under the name “Semley’s necklace”) is one of my favourites, for no single reason I can pinpoint.

This and City of Illusions are probably the two Le Guin novels I like least.

I find the concept of the Hainish cycle interesting, in that there is FTL communication but not FTL travel, and there’s actually a coherent reason why everybody is human (or like enough as makes no mind).

LeGuin deals with the problem of resistance to evil here in a way that presages her treatment of the problem in books to come, I believe. While it’s been decades since I read the book, I recall one scene in which Rocannon is tied to a stake and a fire built around his feet, from which his magi-tech environment suit saves him. To the primitives torturing him, it looks as though he is impervious to the flames, especially as his native clothing burns off and leaves him apparently untouched. When his bindings burn through, even though he could have done what he liked with his torturers, as I recall he simply walks off. Another instance of resisting evil without yielding to it – or am I remembering this correctly? Admittedly they didn’t really do him any harm.

I think comparing this first novel with the rest of Le Guin’s mature work rather misses the point — it stands out when compared with the usual run of novels when it was published. But I agree that the fairy-tale prologue is much better than the novel itself.

I also can’t agree with the statement that, “Though only a few years apart, Rocannon’s World and The Left Hand of Darkness seem to have been written by completely different people.” Rocannon and Genley are cut from the same cloth, clearly colleagues in a shared endeavor, and in similar circumstances on their planets. And what makes The Left Hand of Darkness a tragedy is that Genley, for all his good intentions, is so stuck in his own culture that he is oblivious to the basic facts of the culture(s) he is living in. I think Rocannon might have been a better Envoy to Gethen, but then perhaps The Left Hand of Darkness would not have been so good a book.

Agree with userdavid @@.-@: I also can’t agree with the statement that, “Though only a few years apart, Rocannon’s World and The Left Hand of Darkness seem to have been written by completely different people.” The concern for the “less developed” people in both books was a real revelation after decades of sf stories about “advanced” Earth technology users conquering planets right and left. Written by the same person at different stages of development, sure.

I do agree with the rest of you that “Semley’s Necklace” is a great story, but not because it’s “rendered in the language of medievalist fantasy.” It takes an ancient folklore trope, the visit to Faerie that seems to last only a night but is actually many years, and turns it into science fiction without scanting the sense of loss and tragedy the ancient trope conveys.

I thought for a long time I didn’t like le Guin because of this story.