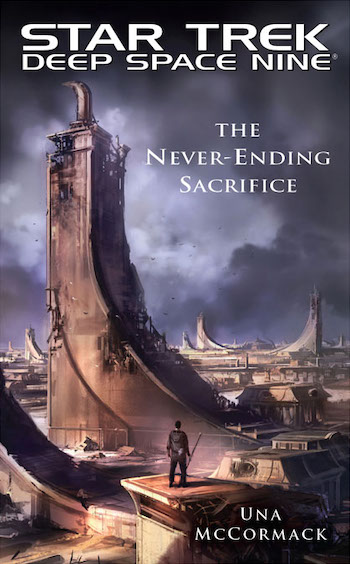

The Never-Ending Sacrifice

Una McCormack

Publication Date: September 2009

Timeline: 2370 through 2378, following the events of Cardassia: The Lotus Flower & Unity

Progress: This is a novel primarily of character rather than plot, so I’m going to keep this summary succinct. Also, the book includes a cross-listing of all the referenced episodes and other stories at the end for your convenience, so I won’t barrage you with links here.

In “Part One: End of a Journey (2370–2371),” we get a brief recap of the events of the episode “Cardassians,” but this time from the point of view of our protagonist, Rugal, and pick up immediately from there with Rugal’s trip to Cardassia Prime and all his subsequent experiences thereon. He struggles with homesickness and with integration into Cardassian society, longing for the Bajor on which he grew up, and wanting to stay as connected as possible to the Bajorans who adopted him, Proka Migdal and Proka Etra. During this time Rugal is often at odds with his biological father, Kotan Pa’Dar, as well as his feisty and prejudiced grandmother, Geleth Pa’Dar. He learns, however, that Kotan’s progressive ideas as part of the Detapa council point to a kinder future for Cardassia, at least theoretically, and he eventually gets to know others—like Tekeny Ghemor (who acts as a nice nexus with the Iliana story of the last several volumes) and his nephew Alon—who, if not quite as outspoken as Rugal, nevertheless appear to share certain reform values.

The most important relationship Rugal forges is with Penelya Khevet, a fifteen-year-old girl who, like Rugal, is a foreigner to Cardassia Prime, having lived on Ithic II until her parents were killed by a Maquis attack. As time passes, Rugal studies to become a medic, his feelings of friendliness toward Penelya deepen into something more, and he becomes an active participant in radical activities, and helps the poor. He also suffers deep losses: Migdal and Etra both die, and after a long and complicated life, so does Geleth.

During “Part Two: A Long Way from Home (2372–2375),” we see Skrain Dukat’s rise to power (the threat of a Klingon invasion serves him well), an ensuing reign of terror, and the eventual alliance between the Cardassian empire and the Dominion. Rugal and Penelya meet Dukat’s half-Bajoran daughter, Tora Ziyal. Penelya realizes that she wishes to return to Ithic, and Rugal, clinging to the hope that he will one day be able to return to Bajor, declines her invitation to join her and continues to live and work at the Torr hospital. Dukat forces him into military service, and so he ends up becoming a glinn on Ogyas III. “Death, food, and the weather. That pretty much covered everything,” is an appropriate summary of his experiences there. The Dominion inflict heavy damage on Cardassia Prime in retaliation for its revolt, and though they lose the war, they still manage to cause massive destruction on the planet, as we’ve seen in some detail in other relaunch books.

In the novel’s concluding section, “Part Three: Return to Grace (2376–2378),” Rugal makes his way to Ithic in search of Penelya. He discovers her abandoned farm and belongings and assumes that she died either at the hands of the Jem’Hadar or in later human-led raids against the Cardassians. During his time at the farm, he meets a war-traumatized human girl named Hulya Kiliç whom he befriends and cares for. When Rugal learns that Bajor has joined the Federation, he decides to pursue the application process for Federation citizenship, and enlists the help of Miles O’Brien, now living on Cardassia, who gets Garak to assist Rugal. After some tense legal proceedings, his wish is granted, and Rugal becomes the first person of Cardassian descent to join the Federation as a citizen. He then formally adopts Hulya, and after paying tribute to the graves of his adoptive Bajoran parents, returns to Cardassia Prime. Against all odds, he is then reunited with a still-very-much-alive Penelya.

Behind the lines: “Surplus to requirements.” This phrase appears three times throughout the course of Una McCormack’s epic yet intimate novel, as various Cardassian characters realize that they may be treated as disposable when circumstances are no longer favorable to them. Besides conveying how Cardassians are treated by the Dominion when the war doesn’t go as planned and the Cardassian resistance rises up, it’s also an ironic reflection of how the Cardassian government treats its own citizens. The relationship between a political regime, and a culture at large, with the individuals that make up that system, is one of the novel’s key themes. The phrase “surplus to requirements” is also apt because of its coldness and detachment, the reduction of lives to a dispassionate balancing of forces that serves to remind us of the speakers’ own attitudes.

After having reviewed McCormack’s first Trek outing, as well as her most recent, it’s impressive indeed to see that with her second novel she not only attained this splendid level of storytelling, but that she approached her subject matter through an unusual form for Star Trek novels, namely the structure of a bildungsroman, to such great effect. For anyone interested in the DS9 universe, or who enjoys historical novels (this one just happens to be set in the future), The Never-Ending Sacrifice is, contrary to the phrase quoted above, very much required reading.

Buy the Book

To Sleep in a Sea of Stars

One realizes the novel’s distinctive approach right away, as we follow Rugal’s journey on Cardassia through successive time jumps—sometimes days, sometimes weeks or months. After the recent spate of DS9 novels, McCormack’s work is particularly noteworthy for the absence of an overt villain. Sure, Dukat is to blame, on a macro-scale, for many of the story’s events, but he is absent for large swaths of the story, and is not positioned, in the narrative, as an imminent threat, but rather a distant, if admittedly insidious, manipulator. The novel’s conflict arises from the characters’ emotional responses to their everyday situations, rather than to some larger-than-life external threat. This focus on internal drama, on a group of largely decent characters simply trying to do the best they can to overcome past injustices in their daily lives, is refreshing, and wonderfully handled.

I invited McCormack to write a guest post for the Locus Roundtable back in 2015, and her thoughts on writing tie-in novels, including some specific comments on The Never-Ending Sacrifice, remain of interest. She mentions A Stich in Time in relation to another one of her books in that piece, and I’d argue that this novel also pays tribute to, and builds on, Robinson’s approach. In a way, The Never-Ending Sacrifice has a flavor reminiscent of the decline of the Roman Empire. McCormack is able to simultaneously evoke the complexity, grandeur and decadence of Cardassian society while unraveling the various political machinations of its leaders.

From a technical perspective, I’d like to point out that this novel contains successful examples, despite what a lot of writing advice claims, of telling the reader how a character is feeling rather than showing it through dramatized action. There are numerous times where McCormack states that a character is angry or whatnot, and this is useful information for us to understand their responses to events, but which it would have been distracting (and repetitive) to show through incident upon incident. To foreground some events, others must be attenuated. Emotions sometimes simmer and linger, and granting us access to these temporally-displaced reactions, when handled with a sure hand, can increase our dramatic investment by adding a sense of psychological realism in a narrative. Rugal, Penelya, even Kotan, undergo experiences that force them to re-evaluate their opinions and ideas—we see this growth, but it accretes continuously rather than crystalizing in a few neat epiphanies.

One such experience that I want to highlight is the power of art—consider Tora Ziyal’s groundbreaking creations—and specifically literature itself. Rugal finds Natima Lang’s The Ending of “The Never-Ending Sacrifice,” a deconstruction and refutation of Ulan Corac’s The Never-Ending Sacrifice, lively, engaging, transformative: “It was very late when Rugal finished reading, by which time his whole world had changed.”

Another sign of Rugal’s maturation and capacity for growth is his ability to accept the sometimes contradictory qualities of those around him, as is eloquently shown in the summation of his relationship with Geleth: “He loved her courage and her indestructibility; he loathed all she had done and all she stood for.” The subtlety of Rugal’s evolution is illustrated in other ways, such as the fact that even when he becomes invested in a cause, he does not lose himself to it. For example, he is cautious not to allow himself to become patriotic, even when his moral compass directs his behavior to align with Cardassian policies. Notice how Rugal makes the distinction when he reacts to Damar’s powerful speech inciting resistance against the Dominion: “He [Damar] did not have Dukat’s charisma, and his words were rough and blunt, but when the transmission got to the end, Rugal realized he was trembling. Not from patriotism, not that…” And later again: “He should get away as soon as he could. But there was still some residual sense of duty left—not patriotism, but responsibility to those poor bewildered survivors he had left up in the mess hall.”

Rugal’s search for his identity and place in the cosmos is an ongoing, open-ended one. The novel decenters us from our standard Federation cast-and-crew perspective in the very first chapter, setting the tone with this line: “Once the accusation had been made, a group of terrifyingly earnest Starfleet personnel appeared out of nowhere and took Rugal away from his father.” That’s how Rugal remembers Sisko and others (not Miles O’Brien, for whom he reserves affection): not as heroes or saviors or paragons of virtues, but instead “terrifyingly earnest.”

Another early poignant moment occurs when Rugal deliberately keeps himself connected to his Bajoran past: “…whenever he caught himself enjoying his surroundings too much, he would press his earring against his palm and let its sharp edges remind him of what and who he really was.” The notions of exile and homelessness come up time and again. Rugal, we are told, was “caught between two worlds, neither one thing nor the other, never at home.” This

inability to be at home is related back to Rugal’s displacement at the hands of Starfleet:

People who had been happy in their homes often lacked imagination; they lacked the understanding that what had been a source of joy for them might be a prison for others. This was the only reason he could find to explain Sisko’s actions—other than cruelty, which did not seem likely in a man that Miles O’Brien respected.

This insight, that much of Rugal’s suffering in a sense stems from the fact that Starfleet personnel who grew up in safer, more privileged circumstances than him failed to empathetically examine the consequences of their decision to have him sent to Cardassia, is powerful and moving. And though it helps Rugal understand, it does not eliminate the need for accountability, and Sisko’s actions aren’t condoned: “Earth explained a great deal—although perhaps it did not excuse it.”

As a being of two worlds, Rugal’s voyage beautifully renders for us various contrasts between Bajor and Cardassia:

For everything Penelya showed him, Rugal told her in return something about Bajor: the fountains and gardens, the pale stone, the silver sound of temple bells on a fresh spring morning. He described the spirited guttering made by trams that miraculously still worked after years of neglect, and the heated political arguments that took place in every street-corner tavern. Everyone was poor, but it was out in the open, not tucked out of sight below bridges.

Later, he comes to realize that in order for both worlds to heal from decades of interconnected violence, Bajorans must also change: “Bajorans have defined themselves as not-Cardassian for far too long. It’s not good for them.”

Returning to the question of craft, another clever technique used by McCormack is to announce future events, or at least signal them, ahead of time. This happens, for instance, when certain characters vow to meet again in the future, but McCormack directly lets us know that they will in fact not see each other again. While this choice would normally defuse suspense, here it imbues the novel’s events with an air of inevitability and tragedy. Again, McCormack’s means perfectly suit her ends. Complementing the time-skipping and the divulging of future turns of fate, McCormack employs parallelisms (as did Olivia Woods) and echoes. One worth singling out is the amazing moment in which a scared, distrustful Hulya first meets Rugal and ends up biting him on the hand—just as he did during his own panicked moment with Garak aboard DS9. In addition to this expansion of temporal vistas, Part Two of the novel opens up on POVs besides Rugal’s. This doesn’t displace the focus away from his story so much as contextualize it in the larger chronicle of the political and social changes sweeping Cardassian society.

McCormack’s descriptive passages remain as evocative as ever, and I especially appreciate her choice to make her descriptions sparse during moments of heightened emotional impact. Penelya’s parting, for example, and Geleth’s passing, both become more affecting because of it. Here’s the death of Rugal’s fellow combatant Tret Khevet:

On the seventh day, when they stopped to rest, Rugal scrabbled around in their packs for some ration bars. He held one out to Tret. Tret didn’t take it. He remained lying on the ground, very still. Rugal knelt down beside him and touched his cheek.

The finest example of all occurs in the novel’s final paragraph, in which Rugal is reunited with Penelya. It’s a beautiful study in understatement.

In a way, the fate of Cardassia may be seen as a parable of our times, a depiction of where the most aggressively capitalist societies of our own age may be headed. As he explores the Cardassian way of life, Rugal reflects that “many Cardassians had strange ideas about the poor. They thought it was a fault of the character, rather than bad luck or circumstance, and they wouldn’t give as a result.” This can certainly be construed as a critique of some of our systems of so-called meritocracy in their lack of compassion towards their poor. Consider the following point, which mirrors Rugal’s comment, made by philosopher Alain de Botton in his thought-provoking book Status Anxiety:

In the harsher climate of opinion that gestated in the fertile corners of meritocratic societies, it became possible to argue that the social hierarchy rigorously reflected the qualities of the members on every rung of the ladder and so thus conditions were already in place for good people to succeed and the drones to flounder—attenuating the need for charity, welfare, redistributive measures or simple compassion.

The reality, of course, is that wealth does not distribute along meritocratic lines, but rather that “a multitude of outer events and inner characteristics will go into making one man wealthy and another destitute. There are luck and circumstance, illness and fear, accident and late development, good timing and misfortune.” Strange indeed, to use Rugal’s word, for us to sometimes think that it would not be so.

Science fiction has the ability to point out the consequences of current trends, and if we think of Cardassia as a stand-in for our worst tendencies, the warning is clear: “If Cardassia could not control its appetites, but could now no longer so casually take from others, then it would eventually start to consume itself. That was the inevitable end of the never-ending sacrifice.” This is reinforced towards the novel’s end: “They had been in the grip of a great delusion—and this was the price.”

Despite being published in 2009, then, this tale continues to provide timely social commentary, beseeching us readers, in turn, to question whether we are living in the spell of our own consumerist delusion. Alberto Manguel, in the final lecture of his book The City of Words, which I happen to have just read, provides a similar end-point warning: our relentless multinational “machineries,” he says, “protected by a screen of countless anonymous shareholders, […] invade every area of human activity and look everywhere for monetary gain, even at the cost of human life: of everyone’s life, since, in the end, even the richest and the most powerful will not survive the depletion of our planet.”

Let’s conclude with a brief comparison of this book to its book within. Rugal finds the prose of Ulan Corac’s (what a fun meta-fictive name) The Never-Ending Sacrifice leaden, and its messaging so heavy as to completely weigh down the text. Despite trying several times, he never finishes the book. Una McCormack’s The Never-Ending Sacrifice is the exact opposite; a masterfully told story, easily absorbed in a span of hours, whose truths emerge naturally from its telling.

Memorable beats: Kotan Pa’Dar: “Mother, the reason I’ve never been much of a politician is that I am a scientist. If you’d wanted me to excel, you’d have left me in my laboratory.”

Tekeny Ghemor: “Kotan said you were distressingly frank. Not a quality much valued on Cardassia, I’m afraid. Obfuscation is more the order of the day.”

Rugal: “Cardassia, where only the military metaphors work.”

Kotan: “Dukat always believes what he says. At least for the moment that he’s saying it.”

Arric Maret: “Some people will always rather be fed and enslaved than hungry and free.”

Garak: “One of my best friends shot me once, and that was a gesture of affection.”

Rugal, visiting the grave of his adopted Bajoran parents: “We are the sum of all that has gone before. We are the source of all to come.”

Orb factor: A magnificent accomplishment; 10 orbs.

In our next installment: We’ll be back in this space on Wednesday June 24th with David Mack’s Typhon Pact: Zero Sum Game!

Alvaro is a Hugo- and Locus-award finalist who has published some forty stories in professional magazines and anthologies, as well as over a hundred essays, reviews, and interviews. Nag him @AZinosAmaro.