In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

Today, we’re going to look at a collection featuring three strikingly different tales by some of the best authors in science fiction: “Lorelei of the Red Mist” by Leigh Brackett and Ray Bradbury, “The Golden Helix” by Theodore Sturgeon, and “Destination Moon” by Robert A. Heinlein. The first story I had long heard about but never encountered. The second is a tale I read when I was too young to appreciate it, which chilled me to the bone. And the third is a story written in conjunction with the movie Destination Moon, which Heinlein worked on; I’d seen the movie, but don’t remember ever having read the story.

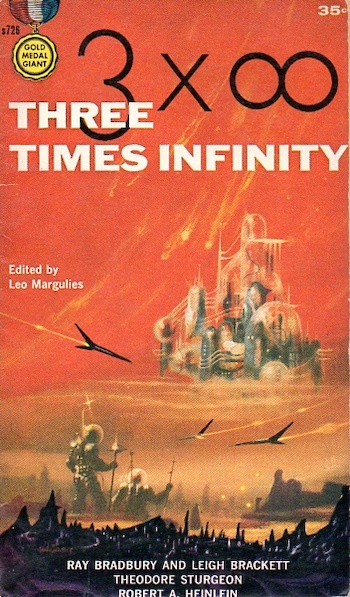

When the paperback book format surged in popularity, science fiction publishers were faced with a conundrum. They had plenty of material from the old magazines that could be reprinted to meet the demand, but those works were generally too short to fill an entire book. One solution was the anthology, where the book could be devoted to an individual author, a common theme, or perhaps stories that fit the description of “best of the year.” Another solution was the Ace Double, a book containing two shorter works, with one cover on the front, and when you flipped book around, another cover on the back. The book we’re looking at today, Three Times Infinity, represents yet another format. It contains three works that, other than their high quality, have nothing at all in common with each other—and there is no preface or afterword explaining how the works were chosen by the editor, Leo Margulies. Margulies (1900-1975) was an editor and publisher of magazines and books in science fiction and other genres. He put this anthology together in 1958 for Fawcett Publications’ Gold Medal imprint.

I found this book among my dad’s collection when my brothers and I were dividing things up after his death and brought it home over a decade ago, but only recently got around to opening the box it was in. I put it near the top of my To Read pile because I had long been interested in reading “Lorelei of the Red Mist,” and you rarely go wrong with stories by Theodore Sturgeon and Robert A. Heinlein.

If I were a more literary-minded reviewer, I might come up some clever thematic way to tie the stories together…perhaps I could show how one story represents the id, another the ego, and the third the superego. But I am not that kind of reviewer, so I will simply say that these tales show the wide diversity of what can be labeled as science fiction, and get on with discussing each of them in turn.

About the Authors

Leigh Brackett (1915-1978) was a noted science fiction writer and screenwriter who today is best known for her work on the script for Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back. I’ve reviewed Brackett’s work before—the omnibus edition Eric John Stark: Outlaw of Mars, and the novel The Sword of Rhiannon—and you can find more biographical information in those reviews.

Ray Bradbury (1920-2012) was a prominent American science fiction and fantasy writer as well as a playwright and screenwriter, who started his career as an avid science fiction fan. I previously reviewed his book Dandelion Wine, and you can see more biographical information in that review.

Theodore Sturgeon (1918-1985) was a much-beloved science fiction and fantasy writer. I have not covered his work yet in this column, so this review is a start at correcting that deficiency. That cause of that oversight is simple—my copies of his best books were buried in a box in the basement, and only recently rediscovered. Sturgeon’s career spanned the years from 1938 to 1983, and he was prolific and widely anthologized. His work had a warmth that of his more science-oriented counterparts often lacked. He also famously coined the saying now widely known as Sturgeon’s Law: “Ninety percent of [science fiction] is crud, but then, ninety percent of everything is crud.” The Theodore Sturgeon Memorial Award is given each year in his honor to recognize the best in short fiction. He was inducted into the Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame in 2000.

Robert A. Heinlein (1907-1988), an iconic and seminal science fiction author, is no stranger to this column. I have previously reviewed Starship Troopers, Have Spacesuit—Will Travel, The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, Citizen of the Galaxy, and Number of the Beast/Pursuit of the Pankera. You will find more biographical information in those reviews.

Three Times Infinity

The story “Lorelei of the Red Mist” has an interesting history. Leigh Brackett was writing it for Planet Stories magazine when she got a call of the sort authors dream of. Noted Hollywood director Howard Hawks had seen her novel No Good from a Corpse, and decided that this “guy” Brackett was just the person he needed to write the script for The Big Sleep, along with famous writer William Faulkner. Science fiction’s loss was Hollywood’s gain, and Brackett turned to her friend Ray Bradbury to finish the tale, which she reportedly had been writing without a clear ending in mind. There is a noticeable change in both prose and tone as the story goes on, although I can’t really say exactly where one writer’s work left off, and the other’s started. The prose is a bit less evocative (or if you are being less charitable, less purple) toward the end than it is in the beginning, but there is a common sensibility and energy to the tale from beginning to the end, so for me at least, the collaboration was a success.

The tale begins with a criminal, Hugh Starke, fleeing the police on Venus after stealing a payroll. His only chance of escape is to try to fly over the mysterious Mountains of the White Cloud. He crashes, and awakens in bed to find himself watched over by a mysterious woman with pure white skin (this woman is the “Lorelei” of the title, but her name is Rann—“Lorelei” appears only in the title as a general term for siren or temptress). Rann tells him that his mind will awaken in a new body, and to his surprise, he does; a body that is bronzed, well-muscled, and black-haired.

Starke is chained and imprisoned by a powerful blind man, Faolan, whose troops are led by a woman, Beudag (this is not the only tale in which Brackett uses lots of Gaelic names, and I sometimes wonder if, in her universe, it was ancient Celts who populated the solar system). Starke discovers that the man who previously occupied his new body was Conan (Brackett reportedly used the name as an homage to Robert E. Howard’s work, but came to regret the decision). Conan betrayed Faolan and his people. Starke attacks Faolan with his chains, and realizes he is doing so at the direction of Rann.

When Beudag arrives, Starke is instantly smitten by this magnificent woman. He tells them his story, and Beudag kisses him, and confirms that the body is no longer inhabited by Conan. Starke learns of the mysterious red sea of mist ringed by the Mountains of the White Cloud, a sea inhabited by a race of people with fins and scales. Some of them emerged from the sea and left the water, and among them is the sorceress Rann. She had captured Conan and turned him against his people, and while being tortured for his crimes, he lost his mind. Beudag, who had once been betrothed to Conan, rekindles her relationship with Conan/Starke, but under the influence of Rann, he tries to kill her.

Conan/Starke is soon drawn into the three-cornered war that wracks this tiny, self-contained society. Rann wants him to lead an army of the undead, made up of the reanimated soldiers lost in recent wars. They will be welcomed back to their home cities, but then turn on those who loved them. While he fights to thwart Rann’s plans, Starke must also prevent her from returning him into his old, dying body. The action is fast-paced, and there are plenty of twists and turns leading to an exciting conclusion.

The story is compact and compelling, and a satisfying tale of redemption. Like many stories of its era, it packs into 56 fast-paced pages enough action to fill a trilogy in today’s market. The hero and the people around him are in danger throughout the entire tale, but while you know he can be knocked down, you suspect he can never truly be defeated.

***

I can’t remember exactly where I initially encountered “The Golden Helix,” but it was at a young age. And it was a scary and confusing experience. The story starts with the awakening of the viewpoint character, Tod. He is part of a team traveling to a far-off Earth colony. The first thing he hears upon regaining consciousness is the screaming of another team member, April. The team is emerging from their suspended animation in “coffins,” ominously named suspended animation cocoons. The other team members are Teague (the leader), Alma, Carl and Moira. But something is wrong with Alma. She is pregnant, and dying, but they can save her six children (humans in this era are prone to multiple births). When they venture out, they discover their quarters have been removed from their ship, and they are on another world, far from both Earth and their destination.

They slowly explore the world, and are working to catalog its often-dangerous flora and fauna, when there is a visitation from some sort of ship and a host of luminous beings. Everyone sees the event a bit differently. The beings form the shape of a double helix (while it is not stated, this is obviously a symbol for DNA), and then disappear, still a mystery. The five survivors do their best to make a life for themselves in this harsh world, but as they have children, it becomes clear that something strange is happening; each child is less evolved than the previous generation.

There is a sense of dread and helplessness permeating the tale that grows more oppressive throughout the story. The original characters spend much of their time suffering from despair. And in the end, while the readers get a glimpse of what the luminous beings were doing, their ultimate purpose remains inscrutable. Sturgeon is a master of his craft, and like all his tales, this one is immersive and compelling, which makes the horror and helplessness of the tale even more effective.

***

While I had seen bits and pieces of the movie Destination Moon over the years, I recently got to view the film in its entirety. Produced by George Pal and released in 1950, the movie was hailed at the time for its realism, and for presenting actual scientific principles instead of fanciful imaginings. By today’s standards, however, the movie plods along at a very deliberate pace, and what seemed new and exciting when it was released is now obvious and clichéd to those who have watched actual moon landings.

The novella “Destination Moon” was adapted from the screenplay, which Heinlein had co-written. I was interested to see what additional details he brought to the story, and how it might differ from what appeared on the screen. The tale follows three leaders of a private effort to send a rocket to the moon: aviation company executive Jim Barnes, retired Rear Admiral “Red” Bowles, and Doctor Robert Corley. They are quite despondent, because they built their nuclear-powered rocket in the Mohave Desert, and now the government is concerned about them launching this experimental nuclear power plant over the middle of the United States (the characters, as well as the author, seem quite dismissive of this bureaucratic meddling in their plans). Why this issue hadn’t been dealt with before the rocket was even built is not clear—the only reason I could think of is to heighten the tension of the narrative. The men decide to take matters into their own hands: with a launch window available in just a few hours, and under the pretense of a dry run, they have the ship prepared for launch. In a decision that feels like wish fulfillment, they decide to crew the ship themselves. After all, what engineer, after designing a vessel, wants to turn it over to some hot-shot youngster to pilot it? (In the movie version, there is a clever little training film that explains some scientific details featuring Woody the Woodpecker, which was echoed decades later in the film Jurassic Park.)

They need an electronics engineer for the trip, and are dismayed to find that their electronics section head has been hospitalized. But one of his assistants, Emmanuel “Mannie” Traub, is willing to replace him. They are suspicious of Traub because he is an immigrant, and are occasionally condescending to him. Along the way, however, we learn that, while he is ignorant about space travel, Mannie is quite competent and brave (and a Purple Heart recipient). Heinlein frequently subverted assumptions about race and national origin in his stories, and I could imagine the twinkle in his eye as I read the passages featuring Mannie. (I should note that the movie whitewashes the character, replacing him with a character named Joe Sweeney).

A government agent arrives with a court order, but the team are already aboard the ship. A truck full of people wanting to stop them is warded off when they turn on the power, and release a bit of superheated steam. The trip to the moon is fairly uneventful; the biggest challenge involves plotting their course properly, and there is much discussion of navigation in space (the movie livens things up with a sticky rotating antenna, requiring a spacewalk that almost goes awry).

Before they reach the moon, Bowles receives orders from the Navy Department recalling him to active duty and ordering him to claim the moon for the United States. When the ship lands, it is just over the horizon, on the “dark side” that does not present itself to Earth. But because of the libration of the moon, they get a glimpse of the Earth and are able to get a message through. They also see some unusual formations in the distance that might be constructed, and not natural, but are unable to explore them. Unfortunately, the blast of steam upon their launch has left them with a questionable amount of fuel left, and while they lighten ship as much as possible, their safe return home is not guaranteed… While Heinlein states that their trip started a new age in outer space, he never definitively says whether they made it home or not.

There is no sorcery in this tale, only cold, hard facts. Even though the protagonists are under threat just as much as in the previous two stories in the anthology, I found this story much less menacing in tone. The challenges of nature and science can be formidable, but they are threats we know.

Final Thoughts

While the anthology Three Times Infinity does not have a single theme, it is an excellent illustration of the breadth of the science fiction field, which runs the gamut from action-oriented planetary adventures, to mystical encounters with powerful forces beyond our ken, to hard-edged examinations of what we might be able to do in the real world. Like a literary buffet, it offers readers a chance to sample a wide range of science-fictional “cuisines.” And as I said at the start, these stories are of high quality, from top-notch authors.

And now I turn the floor over to you: This particular anthology is pretty obscure, but you may have encountered these tales in other anthologies, or seen the movie Destination Moon. If so, I would love to hear your own thoughts. And there are a lot of other anthologies out there, and I am sure you have a favorite anthology of your own to recommend in the comments…

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.

I remember getting this from a library as a young teen. It must have made an impression on me, although I can barely remember any of the stories. “Lorelei” sort of, the Sturgeon story not at all, and “Destination Moon” because of Heinlein and the panic at the end about having to lighten the rocket.

I bought this book in San Jose, I believe, in 1976 at a store where Harlan Ellison read “Emissary from Hamelin” and “Mama”. I was so excited to turn up a Heinlein story I’d never read that I’ve forgotten what I thought of the other two. It’s around here…

I’m almost surprised that there are folks out there who are familiar with the anthology. Until I found it in my dad’s belongings, I had never heard of it. But it did contain some excellent stories, and it was interesting to compare Destination Moon the story with the movie version.

One of the most amazing things about The Golden Helix is that it was written BEFORE the discovery of the DNA helix!

I might be the only gen z-er who’s read this anthology. I picked it up randomly at a used bookstore. The policy was that a book was half-off if there was no price affixed, but alas, they charged me $3 instead of the promised 17.5 cents (I didn’t complain).

I remember Brackett’s story the best out of all these, and I enjoyed it a fair amount. Not the best thing I’ve ever read, but there is something fun about that old-fashioned sword and planet stuff. I remember the Heinlein decently well, but I was a bit bored by it. I felt like a lot of the value of the story was in the audacity of actually getting to the moon, but since I know that’s not how it played out, I wasn’t so entertained. (Though I’ve also realized that I’m not that big a Heinlein fan in general from reading a couple other books by him.) The Sturgeon story I only have the vaguest of memories about.

Bizzare coincidence, i have just been trying to collect katherine maclean stories and the only copy of orbit one i could get on ebay came as a pair with this book. So it is on its way to me now.

I have lots of these 3 novella collections, as a young girl sf anthologies were the way i got my intro to most of the classic writers.

@@.-@ If I am reading things right after a quick Google search, Crick and Watson identified the structure of the DNA molecule in 1953, while the story was first published in 1954. So it appears Sturgeon was right on top of cutting edge science, not ahead of it.

@6 That is a coincidence. You should enjoy the collection.

I read this anthology just last year, acquired it because I’m a Heinlein fan. The Heinlein story was fine but familiar, a lot of its plot is taken from Rocket Ship Gaileo. The climax is exciting. The Lorelei I found insufferable: outdated old fashioned fantasy. The Sturgeon story is great: the travails of the spaceship survivors on a strange planet are already interesting, and the unfolding of the broader scheme causing the backwards evolution is majestic. 4 out of 10 for Brackett, 7 for Heinlein and 9 for Sturgeon.

I actually just read Lorelei (in the Haffner Press collection of the same name) recently and enjoyed the heck out of it, but didn’t know how or why it had turned into a Brackett/Bradbury collaboration, so I’m glad to know the story.

@7 Sturgeon wrote notes on the creation of The Golden Helix for a collection of his stories*. In it he said that he had written the story before Crick & Watson published their findings on the structure of DNA. Sturgeon didn’t claim that he had predicted that outcome (he may even have said that explicitly), and in the story it’s pretty clear that the helix formed by the aliens is a symbol for the process of evolution (& devolution). I don’t know if the copyright date would be any help in confirming Sturgeon’s claim, but I’m inclined to believe him in any case.

* It’s possible that the collection was _The Golden Helix_ but the story has appeared in multiple collections so no guarantee.

@10 Thanks for that background. If that’s what Sturgeon said, I’m willing to accept his word on the subject, as it is entirely possible he wrote the story before hearing news about the discovery.

“By today’s standards, however, the movie plods along at a very deliberate pace, and what seemed new and exciting when it was released is now obvious and clichéd to those who have watched actual moon landings.”

What an awesome sentence to be able to write. I actually enjoyed the movie, but more for a glimpse into the minds of the past about the future (basically the way I enjoy old imagined ads for flying cars).

Coming in late, but I’m surprised nobody mentioned the famous story about Heinlein helping Sturgeon with writer’s block.

@13 Carl. Didn’t share it because I didn’t remember it. Please fill us in!

@AlanBrown, Sturgeon used to tell the story of being completely blocked, of having no ideas, of thinking in the worst moments that his career was over.

He told Heinlein about it in a letter. By return mail, Heinlein sent him 26 story ideas, and according to Sturgeon this broke his writer’s block, which seemingly never returned. He remained grateful to the end of his life. Apparently when heard of Ted’s distress, RAH just sat down and wrote this multipage masterpiece and mailed it back two days later.

https://lettersofnote.com/2012/10/01/the-heinlein-maneuver/

EDIT: he also included $100 in 1955 money, just because he figured Sturgeon was probably short at that moment because of the dry spell.