CJ Cherryh’s long-running Foreigner series has a lot of interesting linguistics in it. One of her specialties is writing non-human species (or post-human, in the case of Cyteen) with an almost anthropological bent. Whenever people ask for “social-science fiction,” she’s the second person I recommend (Le Guin being first). These stories usually involve intercultural communication and its perils and pitfalls, which is one aspect of sociolinguistics. It covers a variety of areas and interactions, from things like international business relationships to domestic relations among families. Feminist linguistics is often part of this branch: studying the sociology around speech used by and about women and marginalized people.

In Foreigner, the breakdown of intercultural communication manifests itself in a war between the native atevi and the humans, who just don’t understand why the humanoid atevi don’t have the same feelings.

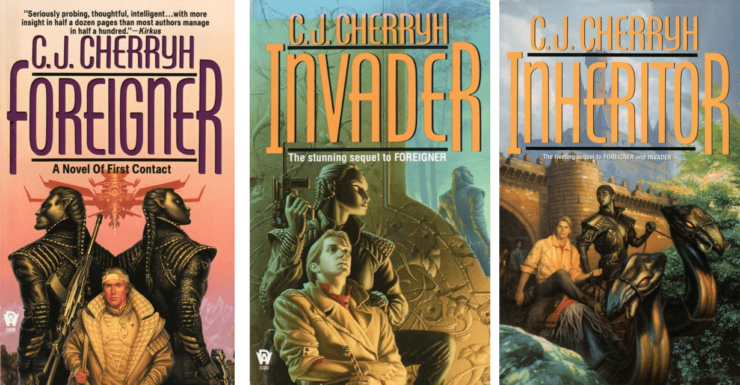

The first trilogy of (currently) seven comprises Foreigner, Invader, and Inheritor, originally published from 1994-96. It opens with a human FTL ship missing its target and coming out of folded space at a white star that isn’t on any of their charts. The pilots and navigators find a more hospitable destination and after some time spent refueling, they head there. Once they reach this star, they find a planet that bears intelligent life—a species that has developed steam-powered engines and rail. Some of the humans want to drop to the planet and live there instead of in the space station, while others want to stay on the station and support the ship as it goes searching for the lost human stars.

A determined group of scientists build parachute capsules and launch themselves at an island that looks less densely occupied than the mainland, where they build a science station and start studying the planet’s flora and fauna. At one point, an ateva encounters a human and essentially kidnaps him to find out why they are on his planet and what they’re doing. This initiates a relationship between two species who each assume the other is biologically and psychologically like they are. Humans anthropomorphize everything from pets to Mars rovers, so why wouldn’t we project ourselves onto humanoid species from another planet?

Atevi are psychologically a herd species. They have a feeling of man’chi (which is not friendship or love) toward atevi higher than themselves in the hierarchy, and they associate themselves (again, not friendship) with other atevi based on their man’chi. Humans, not understanding this basic fact of atevi society, create associations across lines of man’chi because they like and trust (neither of which atevi are wired for) these atevi who have man’chi toward different (often rival) houses. This destabilizes atevi society and results in the War of the Landing, which the atevi win resoundingly. Humans are confined to the island of Mospheira, and they are allowed one representative to the atevi, the paidhi, who serves both as intercultural translator and as intermediary of technology. The humans want to build a space shuttle to get back up to the station, you see, and they need an industrial base to do so. Which means getting the tech to the atevi—who, in addition, have a highly numerological philosophy of the universe, and thus need to incorporate the human designs and their numbers into their worldview and make them felicitous.

With this background, the real story opens about two hundred years later with a focus on Bren Cameron, paidhi to the current leader of the Western Association of atevi, Tabini-aiji. Unbeknownst to Bren, the ship has returned to the station, which threatens to upset the delicate human-atevi balance—and forces the space program to accelerate quickly, abandoning the heavy lift rockets already being designed and shifting to the design and production of shuttlecraft. This exacerbates existing problems within atevi politics, which are, in human eyes, very complicated because they don’t understand man’chi.

Throughout, I will refer to “the atevi language,” but Bren refers to dialects and other atevi languages than the one he knows and which the atevi in the Western Association speak, which is called Ragi. Atevi are numerologists; the numbers of a group, of a design, of a set of grammatical plurals, must be felicitous. This necessitates an excellent mathematical ability, which atevi have. Humans don’t, but with enough practice, they can learn.

Bren’s attempts to communicate with the atevi using terms he understands only imperfectly, because they don’t relate perfectly to human psychology, are an excellent example of how intercultural communication can succeed and break down, and how much work one has to do to succeed. Bren frequently says that he “likes” Tabini and other atevi, like Tabini’s grandmother Ilisidi and Bren’s security guards Banichi and Jago. But in the atevi language, “like” is not something you can do with people, only things. This leads to a running joke that Banichi is a salad, and his beleaguered atevi associates put up with the silly human’s strange emotions.

When the ship drops two more people, at Tabini’s request, one heads to the island of Mospheira to act as representative to the human government, and the other stays on the mainland to represent the ship’s interests to the atevi and vice versa. Jason Graham, the ship-paidhi, gets a crash course in the atevi language and culture while adapting to life on a planet, which is itself a challenge. He has no concept of a culture outside of the ship, or that a culture could be different from his own, and he struggles with atevi propriety and with Bren, who is himself struggling to teach Jase these things.

Buy the Book

A Psalm for the Wild-Built

One of the things Bren tries to pound into Jase’s head is that the atevi have a vastly different hierarchy than humans, and the felicitous and infelicitous modes are critically important. Bren thinks, “Damn some influential person to hell in Mosphei’ and it was, situationally at least, polite conversation. Speak to an atevi of like degree in an infelicitous mode and you’d ill-wished him in far stronger, far more offensive terms”—and may find yourself assassinated.

Even the cultures of the ship and Mospheira are different, because life on a ship is much more regimented than life on a planet. Jase likes to wake at the exact same time each day and eat breakfast at the exact same time each day, because it’s what he’s used to. Bren thinks it’s weird, but since it’s not harming anyone, he shrugs it off. Their languages are similar, because they’re both working primarily from the same written and audio records, which “slow linguistic drift, but the vastly different experience of our populations is going to accelerate it. [Bren] can’t be sure [he’ll] understand all the nuances. Meanings change far more than syntax.” This is, broadly speaking, true. Take the word awesome, which historically means “inspiring awe,” but for the last forty years or so has meant “very good, very cool1 .”

The ship has been gone for around 200 years, which is equivalent to the period from today in 2020 to the early 1800s. We can still largely read texts from that time, and even earlier—Shakespeare wrote 400 years ago, and we can still understand it, albeit with annotations for the dirty jokes. On the other hand, the shift from Old to Middle English took a hundred years or so, and syntax, morphology, and vocabulary changed extensively in that period. But because we can assume that the ship wasn’t invaded by the Norman French while they were out exploring, it’s safe to assume that Bren and Jase are looking at a difference more like that between Jane Austen and today than between Beowulf and Chaucer.

When Jase hits a point where words don’t come in any language because his brain is basically rewiring itself, I felt that in my bones. I don’t know if there’s scientific evidence or explanation for it, but I’ve been there, and I’d wager most anyone who’s been in an immersive situation (especially at a point where you’re about to make a breakthrough in your fluency) has, too. It’s a scary feeling, this complete mental white-out, where suddenly nothing makes sense and you can’t communicate because the words are stuck. Fortunately for Jase, Bren understands what’s happening, because he went through it himself, and he doesn’t push Jase at that moment.2

When Jase has some trouble with irregular verbs, Bren explains that this is because “common verbs wear out. They lose pieces over the centuries. People patch them. […] If only professors use a verb, it remains unchanged forever.” I had to stop on that one and work out why I had an immediate “weeeelllllll” reaction, because I wrote my thesis on irregular verbs in German, and data in the Germanic languages suggests the opposite: the least-frequently-used strong3 verbs are the most likely to become weak, because we just don’t have the data in our memories. On top of that, a lot of the strong and the most irregular verbs stay that way because they’re in frequent (constant) use: to be, to have, to see, to eat, to drink. We do have some fossilized phrases, which Joan Bybee calls “prefabs,” that reflect older stages of English: “Here lies Billy the Kid” keeps the verb-second structure that was in flux in the late Old English period, for example. The one verb that does hew to this is to have. I/you/we/they have, she has; then past tense is had. This is a weak verb, and, strictly following that rule, it would be she haves and we haved. But clearly it isn’t. This verb is so frequently used that sound change happened to it. It’s more easily seen in German (habe, hast, hat, haben, habt, haben; hatte-), and Damaris Nübling wrote extensively about this process of “irregularization” in 2000.

Atevi culture, not being the (assumed Anglophone) human culture, has different idioms. Here are some of my favorites:

- “the beast under dispute will already be stewed”: a decision that will take too long to make

- “she will see herself eaten without salt” because of naïvete: one’s enemies will get one very quickly

- “offer the man dessert” (the next dish after the fatal revelation at dinner): to put the shoe on the other foot

So! What do you all think about the plausibility of a language that relies on complex numerology? Do you think the sociological aspects of the setting make sense? Are you also a little tired, by the time we get to Book 3, of the constant beat of “atevi aren’t human, Bren; Banichi can’t like you, deal with it”? Let us know in the comments!

And tune in next time for a look at Cherryh’s second Foreigner trilogy: Bren goes to space and has to do first contact with another species and mediate between them and the atevi, too! How many cultures can one overwhelmed human interpret between?

CD Covington has masters degrees in German and Linguistics, likes science fiction and roller derby, and misses having a cat. She is a graduate of Viable Paradise 17 and has published short stories in anthologies, most recently the story “Debridement” in Survivor, edited by Mary Anne Mohanraj and J.J. Pionke. You can find her current project, a book on practical linguistics for writers, on Patreon.

[1]Which, of course, has its own history of semantic change.

[2]This is different from the somewhat embarrassing situation where you think of the non-native word first and have to circumlocute the native word and get your students to tell you what it is.

[3]Germanic linguists use this term, coined by Jacob Grimm (yes, that one), to indicate the set of verbs that shows regular stem vowel changes in their tenses, like sing-sang-sung or eat-ate-eaten. Weak verbs take -ed in the past tense forms, like walk-walked. We use it to distinguish between verbs with regular patterns and truly irregular verbs, like to have or to be.

This was the most requested book/series when I started this, so I hope you all enjoy it!

what a wonderful article. I really enjoyed the linguistic context.

I adore these books. As a former anthro major it felt like they were made for me, because it dug into alien’s alienness in such a satisfying way. While the series has its fault it’s definitely an all-time favorite.

While the “atevi aren’t humans” is very repetitive, now that I’m on book 20 I mentally put it in the ‘this is here in case some rando picks up in the middle of the series’ box like the brief previous book plot summaries. Not really needed but I get why it’s there.

It’s been awhile since I’ve read the early books, but I took a lot of the numeralogical grammer stuff to be really complex word agreement that happens to necessitate fast mental math–not necessarily doing huge equations in your head so much as keeping track of a lot of numbers and how they break down or relate to others while speaking. IIRC a lot of the on-page mentions are if something is odd, even, or prime, which is fairly straightforward but definitely a lot to juggle if you suck at numbers. I feel like that’s not too ridiculously complex to be completely unrealistic for speaking. I assumed it was other cultural emphasis on numbers that demanded actual math skills.

Regarding the second footnote, I’m not sure if this is the same situation but one of my favorite things is when there’s a language learning brain fart and people use awkward phrases because they can’t quite remember the actual word–like calling pears “apple’s friend.” What people come up with can be fascinating!

Love the Foreigner series, and happy you are making a go of this as an ongoing series.

Those new to it should realize that the first half of the first book (Foreigner) is highly disorienting on purpose, causing some to give it up. If you stick with it, the plot and cultural issues start making sense by later in the first book and then it goes on from there to become both more understandable and increasingly complex – but you gain the tools to understand the complexity as you move forward. It is a deep dive into alien cultures (I consider the atevi, the Mospherians and the ship folk all to be alien by our standards) that is entertaining and compelling.

Thanks for the excellent write up on one of my all time favorite series. The one thing I’d add, especially for those just starting the first books, is pay attention to the plays. The atevi have a form of theatre called machimi, and references to machimi plays are made regularly throughout the books. It’s in those references that you can find out how events are being perceived and interpreted by the atevi.

I’ve always loved the “salad” joke and I also love reading the occasional unexplained references to it in later books… Banichi just wryly saying like, “Salads” and long-time readers get it, because they’ve immersed fully into the setting to know what it means. I always have this sense, in reading these books, of ‘understanding’ the conlang itself, and trying to almost want to use phrases like “baji-naji” ha. The language and culture building is really so good, and the sense of the atevi as really alien and just almost understandable if both sides are trying, like we see happening later on with the space station crews.

I love this series as well! Most of what I read leans toward “hard” science fiction but this series is just so well written that I scoop up the latest book in the series as soon as they come out. When language plays such a big role in a story, I develop my own idea of what it sounds like. I agree with an earlier commenter that the three groups-stationers, Mospheirians and Atevi are essentially separate cultures, with perceived similarities being deceiving and words not always having a one-to-one correspondence. Looking forward to more articles!

I loved all the little bits of business like…

* An important atevi makes an important speech, but instead of playing on the emotions of his audience with words, he uses their number-sense by incorporating a count that must be completed in order to avoid causing visceral discomfort and then…not completing it

* Atevi, ship-humans, and planet-humans developing a common catchphrase to cover all the counterintuitive things they have to do in order to get along in space: “Gravity doesn’t care!”

* The absolute importance of a particular way of handling food items, such that a fish farm must incorporate a randomized automatic fish-scooper in order for the animal husbandry to be “right”

* The sect that practices a kind of universal benevolence, but in atevi terms it’s the extension of man’chi to all–and, as said before, not actually love

Going back to the first item, I got the impression that atevi numerology was developed on a foundation of a deep emotional reaction to certain symmetries. In our species, we usually see this in neurodivergent people, but it seems to be baseline for them.

Thanks for a great article; I hope it’s the first of many.

I love this series, partly because the hero is a translator. Cherryh is great at making aliens really feel alien, and the mechanics of atevi language are fascinating to watch.

plus I love the jokes. Like when Deana Hanks is identified in the firefight on the beach by her linguistics errors. “Are you sure it’s Hanks?” “She appealed to us to disintegrate and abase our weapons.”

On the serious side, however, one could argue that Hanks’ linguistic inflexibility, arising from her ideology, led to her death, because she literally failed to understand what atevi were saying.

I’ll buy a book just because it has Cherryh’s name on the cover. She is a master world builder, and she is at the peak of her game in the Foreigner series. She also tells a rouser of a tale. She’s been writing quite a while, and if you like the Foreigner books, take a browse through her extensive (80+ books) back catalog.

I’ve reread the Foreigner books several times. They stand the test of rereading — so richly detailed is the Foreigner-verse that, as many times as I’ve reread them, I still keep finding details I missed. My hands down favorite character is the Dowager Ilisidi.

Man’chi sounds awfully like loyalty. What are the differences?

@Jenny & msb – I have so many notes written in my notebook about things like this, and I love it. I love the speech Tabini gives where he leaves his audience hanging, waiting for felicitous 3. I love Hanks’ terrible Ragi because she dgaf about it, just power. I love Jase’s terrible Ragi but at least he’s trying and how Bren recognizes a note he left because of the “pretty good but not quite there yet” grammar. I’m pretty sure it was Jase who mis-pronounced assassins as “noble thieves,” which I also loved.

I’m about to re-read the 3rd trilogy, and I have the next post drafted & waiting in the wings. At this point, there have been so many books that I can’t remember which bits happen in which ones, so the one after that might be about Cajeiri and his human friends, or it might be 2 after.

@11 – man’chi is innate. You are born with man’chi in a particular direction, and you feel it toward atevi above you. Man’chi does not flow downwards: the aiji has no man’chi to anyone. This is what makes them aiji-in. One of the tragic turns in the machimi plays someone mentioned above is that a character has man’chi in a direction they didn’t know about and now their closest associates are their enemies.

Loyalty is a human emotion, and it’s somewhat mutable, is it not? Loyalties can shift and change over time. Man’chi does not.

As far as a language based on numerology, we have Hebrew.

I’ve only read the first trilogy, time to revisit it prior to continuing the series!

What happens if two atevi are born that don’t feel man’chi toward anyone? Do they fight to determine who is aiji?

@13 Hebrew can be interpreted numerically, but there’s no need to know any of the equivalences or do any mental math just to speak a sentence.

@15 Pretty much, yeah, though there are lower-level regional aiji-in, kind of like there’s a king/queen of England and a bunch of dukes and barons and whatnot. One of the institutions created after the human problem started is the Western Association, which elects the head aiji through its equivalent of the House of Lords, if an aiji dies without a named heir.* How the lords decide who they vote for isn’t really explained, though it seems, through Bren’s interpretation, to be based on common political or economic interests, but also how their family feels about the family of the candidate in question.

*This happens pretty regularly, because assassination is a fine and legal way of taking care of your problems. It can also cause problems, because it can leave a power vacuum in an area and you don’t know which way the survivors will jump. This is a pretty major plot point in … book 3, I’m pretty sure, but as I said above, they’ve all run together in my head, then it comes back with a vengeance in book 7.