Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches.

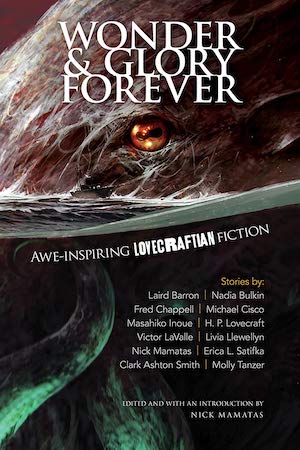

This week, we cover Livia Llewellyn’s “Bright Crown of Joy,” first published in Ellen Datlow’s Children of Lovecraft anthology in 2016, and reprinted last year in Nick Mamatas’s Wonder and Glory Forever anthology. Spoilers ahead, but this one is very much worth tracking down and reading yourself.

“After the After, there were waves of tsunamis that circled the surface of the world again and again, remaking it entirely new, there were epochs of monstrous and amazing creatures that thrived and died off in mass extinctions as the planet recalibrated again and again, as we who survived realized that we too had recalibrated, and were part of the chain of change.”

AFTER: In the time that her PrionTech Interdiary implant labels “[::AFTER::],” narrator thinks about birds. Millenia have passed since her girlhood, and birds are extinct, like most animals that her fellow half-humans remember; gone, too, are dry lands and cold seasons. Over narrator’s roofless chamber, gelatinous creatures swim through hot damp air. They’re the birds now.

The companion she thinks of as “the boy” is “hardly a boy anymore but something caught between boy and alien wonder.” Frequently they press together while “flickering images of past lives [wash] through [their] conjoining flesh and minds.” But this morning they have business on the last mountaintop, where their children await.

MEMORY (July 17-18, 24—, high on Mt. Baker): In narrator’s (incomplete) Interdiary entry, she wakes to the dream-echo of “He is coming.” From her window she sees slopes dotted with “pockets of light,” homes of others rich enough to afford 24-hour electricity. The forests already sport gold-red swathes—Autumn comes earlier every year. People say this will be the final die-off. It’s been seven years since the Pan-Pacific tsunami waters receded.

Tonight she’s going with a banker date to the stronghold of the mega-rich Ballad family. Dressing, she remembers her dream of “a constant thunderous ringing as all the oceans of the world pour up into the sky, and everything sinks below.”

AFTER: Narrator and the boy traverse the marshy jungle covering the last ancient peaks. Instinct guides them; in the “wondrous order of [their present],” they forget the “limit of finite days.” Yet the prospect of becoming part of Time, vast and endless, sometimes makes them weep.

They sail a skiff over drowned cities to the summit crowning Earth’s last land mass. A man greets them, an elder with fingerless hands and facial features subsumed—he breathes now through his skin. Faded purple light sputters at his temple, but his Interdiary has long ceased functioning. Like all semi-humans except narrator, he lives “a memory-free, streamlined evolution into the future.”

MEMORY: At Ballad House, less mansion than nuclear bunker, party guests are escorted to view a rare wonder. From a courtyard, narrator waits beneath an unseasonable aurora. She stumbles to a bench, telling her date she’s not drunk, it’s “just the stars. It’s just the bells.”

AFTER: Narrator, boy, and man enter a school. Algae bursts from linoleum floors and sea-grass protrudes from rusted lockers. They descend to the “underground rivers, bioluminescent rooms, and glittering nocturnal pools” where children and elders “reside as a single entity” whose song narrator hears only as “a faint impulse.”

Below, the bodies of children and elders meld into one living mass. United, they flow down into a being that will someday consume Earth and travel “the dark river of stars” to another world, there to dream until “the time is right once again for the cycle of life to repeat.” Narrator feels the melders’ thoughts as “declarations of familial love, equations and astral projections and all the cosmic revelations that come with pending godhood.” She breathes easier, feels her aches fade. She gives the children what she alone preserves: “the glimpse of our future-self.”

MEMORY: Narrator’s group follows their host down a tunnel to a heavily fortified door. In an antechamber, they don Arctic gear. A boy around fifteen, the host’s son or the son’s donor-clone, joins her and her date. He makes them an amazing offer for later, which they accept. Then the inner door opens to cold and—snow.

AFTER: Narrator and the boy leave the melding space for a classroom occupied by the narrator’s still nearly human children. For ages she and other once-female elders lay under the sky while eggs poured out of them. Countless times she’s come to the school to cocoon with the resulting children, opening her mind so they can see what she saw rise, millennia before. Their bodies drape over her, over each other. All must connect, for so they communicate and learn. Delicate fingers touch narrator’s temple-port, and—

MEMORY: Narrator, her date and the boy are on the Ballad House roof. The boy shows them how to use a powerful telescope. Most people look for the remnants of their former homes. Narrator asks the boy to show her the ocean. She wants to face her enemy, her future.

Buy the Book

Star Eater

The ocean, moon-silvered, looks benign. Then a wave rises, a tsunami. He is coming…

Sirens wail. Everyone rushes inside except narrator and the boy. Through the earth’s convulsions, she clings to the telescope and tells him what she sees. A wall of water, deep green and blue, the colors of a crown. Light wells from it, liquid fire. It engulfs land, mountains, so fast, but—it’s not water! It’s—He’s—Everywhere eyes, and she sees—

AFTER: She and the boy leave the children to begin tranforming into the thing they saw in her mind. There are few eggs left; the birthing part of the cycle is ending. Does she feel melancholy, or anticipation? Curiosity, wonder and joy, all things the universes cannot feel? This time will they all unite into a being that rejects nothing, accepts all? Will there be no more dreaming?

MEMORY: …in the snow-room stands the last bit of glacier on Earth. It’s dirty-gray, not the pearly river of old pictures, but there’s one spot of brilliant white worn into the ice by years of supplicating hands. Narrator’s presses it in her turn. The pain is delicious, for she touches the heart of the world. She is this world, connected to all life. She’s not insignificant anymore.

[::LOCK::]

What’s Cyclopean: A broken Buddha statue, worn down into the featureless aerolith from which it was born, is in fact “cyclopean.”

The Degenerate Dutch: In memory, Narrator is one of the elite, “rich and jaded and cruel,” interested primarily in courting the protection of those richer and crueler and more jaded. They do have limits: they “could never eat that.” Whatever “that” grotesque party snack is.

Weirdbuilding: We never do find out who He is, but given His association with rising seas and cataclysmic change, we can probably guess.

Libronomicon: Does Narrator’s diary implant count as a book?

Madness Takes Its Toll: Humanity is becoming something without consciousness or individuality. Familiar modern mental states don’t enter into it.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Have I mentioned lately how grateful I am to Anne for writing our summaries? She regularly comes up with succinct run-throughs of poetry, post-post-modern literary analysis, and stream-of-altered-consciousness monologues, providing context for our commentary and occasionally giving me a pre-publication heads-up that I’ve wildly misinterpreted a story’s conclusion. I mention my gratitude this week for reasons.

The stories that are the most difficult to summarize are also, often, among the most rewarding to read, and “Bright Crown of Joy” is a case in point. A semi-linear run through the plot points necessarily glosses over the gorgeous descriptions of far-future ecology, the somber-yet-joyful moodiness of the ancient narrator, and the way the whole story dances around memories missing or withheld.

I picked up Mamatas’s Wonder and Glory Forever reprint anthology following a shared Balticon panel, due both to the title (quoting one of my favorite Lovecraft lines) and the theme of cosmic horror with the emphasis on cosmic, on awe rather than fear. On that panel, discussing Mythos stories set in different eras, I talked about how easily Lovecraft’s work maps to every imminent apocalypse since World War I. Llewellyn manages both apocalypse and awe, shifting between the throes of all-too-near-future climate change and, strange aeons later, a world as changed from our own as ours is from the Jurassic—and planning an eldritch gray goo apotheosis even further from comprehension.

Though I think I comprehend a hint or two. That mass of undifferentiated, ecstatic flesh that will eventually eat the world and travel the stars to seed life elsewhere? Pretty sure that fits the bill for a proto-shoggoth. And explains, as Lovecraft never did, exactly what’s so terrifying (and wondrous) about it. [ETA: Anne thinks it’s New-Cthulhu, also a possibility. Or they could be the same thing.]

Everything I’ve been reading lately seems to involve neural implants or memory or both. (Arkady Martine’s A Desolation Called Peace has implants that preserve memory to be passed from the dead to the living, and explores the possibilities raised by connections between minds. Sarah Pinsker’s We Are Satellites offers implants to make us better, smarter, more efficient with our attention. Karen Tidbeck’s The Memory Theater has memories magically lost, stolen, and sought.) “Bright Crown” does both, walking the line between straightforward science fiction—the journal implants—and fantasy where magic is merely the universe pointing out how little science we know.

Narrator’s journal implant starts as a much-leaned-on prosthetic memory, propping up her sense of individual identity. Aeons later, the only such device remaining, it feeds humanity’s remaining sense of collective identity, and the proto-shoggoth’s sense of purpose. Individuality is obsolete, but Narrator hasn’t quite let go. After all, “when you’re the last, it means you can find out little things the ones who went before you didn’t know, secrets and cheats. Sometimes you learn how to stay as long as you want.” Narrator can afford to linger, still recording memory through deep-time eras of geology and biology and psychology.

And eventually, what memories will drive the proto-shoggoth’s journey? There’s the coming of him, rising along with the ocean. And then there’s that last, lost memory, from earlier in the night: that final piece of glacier. It’s a horrific image, both because of the loss of the icecaps themselves, and because the orphaned ice is holed up in some trillionaire’s vault to be shown off at parties. And yet combined with the Rise of something that makes that trillionaire insignificant, it retains something sublime. It offers meaning even in the face of the cosmic.

I hope the proto-shoggoth, driven by that inaccessible memory, finds a nice cold planetary pole to settle in. And that—unlike the one who initially came to Earth—it finds people who appreciate its significance.

Anne’s Commentary

Have you ever eaten chocolate of so high a cocoa intensity that sugars can only have given it a sidelong glance? Llewellyn’s “Bright Crown of Joy” is like that chocolate: dark and dense, with an excruciatingly slow melt and a complex bitterness that lingers long after the confection is swallowed. If I may extend the simile, “Bright Crown” is like a high-intensity chocolate with cacao nibs, those gritty shards of the ground bean loaded with nutrition (“Bright Crown” is good for you!) and the capacity to wound (“Bright Crown” might get stuck in the dental-mental work of your psyche, and yes, I’ll stop now, but damn, I have figuratively nailed this story.)

There’s a traditional gospel song called “Down in the River to Pray.” When Llewellyn’s story wasn’t making me reach for the Ghirardelli, it made me think of these lyrics:

As I went down in the river to pray

Studying about that good ol’ way

And who shall wear the starry crown

Good Lord, show me the way

Our unnamed narrator doesn’t have to go down to any river, however, because the whole ocean is coming for her. The year of the Just-Before-The-After times is somewhere in the 2400s, and climate change has lived up to its advance billing. Waves of super-tsunamis have made mountain real estate the new oceanfront property, the higher up the slopes (and further from the beach) the pricier. And it’s hot—the last bit of glacier is no bigger than a truck and has to be kept under deep refrigeration, so precious an artifact even its mega-rich caretakers don’t dare chip bits to cool their cocktails.

Narrator studies about the good ol’ ways because somebody has to do it. Before-Times people apparently became dependent on a cloud system accessed by brain implants, PrionTech being one implant manufacturer and the purveyor of apps like InterDiary and DreamCatcher. Narrator was a big user of InterDiary, which is why she retains potent and poignant memories, some file corruptions notwithstanding. As all other previously human survivors have dead or malfunctioning implants, she’s become the race’s archives.

Archives? Isn’t that too grand a term for what narrator retains? It might be, except for her ultimate Before-memory of the “starry crown” and Who/What was wearing it as He rose, vast as the sea, the jewel blues and greens of the waters His glorious topper. It’s a starry crown, too, for stars or comets move behind it, “little sparkles of white light.”

Narrator’s the sole surviving eye-witness to the moment when a new Lord cleft the Before from the After. She doesn’t name Him, but we know this Dreamer must be our old friend Cthulhu. In “Bright Crown,” His ruling purpose doesn’t seem to be indiscriminate joyful ravening. He’s a cosmic Change Agent, a Remodeler of Worlds into His Own Image. To see His Face is to enter a transformation into—Himself.

Narcissistic much, Big C?

Because she’s the only previous-human retaining access to her memories, narrator’s the only one truly retaining an individual self—even the boy is slipping away into the collective. Thus narrator is torn in her view of humanity’s destiny. Is Cthulhu the ultimate egotist, a deliberate destroyer of worlds, or is He one more creature simply obeying its biological imperative? Of this narrator is sure: There’s a cycle of life which even He must follow. From a relatively minuscule spark, a dormant dreaming spore, He awakens to transform the life-forms of His host planet into a single living mass that then consumes the planet and returns to starry peregrinations in search of another planetary rest stop and incubator.

Narrator’s quandary is whether His Coming is a Good or a Bad Thing. It’s stupendous, all right, but stupendous-beautiful or stupendous-terrible? Can it be both? Unlike oceans and mountains, nature, the insentient universe, narrator is a being of complex emotions. Contemplating the end of the After-Times, she feels melancholy, anticipation, curiosity, wonder and joy. Her memory of touching the last glacial ice was one of connection to “the heart of the world,” to “life, ancient and incomprehensible.” She became this world, she was no longer insignificant, but she was still herself.

When she finally slips through the oculus, melding into the collective, will that experience be similarly transcendent? Will she and those gone before her share His starry crown? She doubts that’s been the case in other cycles of His life, yet she hopes this time will be different. Perhaps her stubborn bit of PrionTech circuitry will make a monolithic One into Many-in-One, an entity for whom “no one will be forgotten, and everyone remembered.” A death in which she will not die, in which no one has ever died, but she will “join everyone [she] has ever loved and birthed and known.”

In that case, Good Lord, show her the way. Otherwise, never mind. Not that You’re offering the choice.

Next week, we continue T. Kingfisher’s The Hollow Places with Chapters 15-16, in which Kara has some very bad dreams.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her short story collection, Imperfect Commentaries, is available from Lethe Press. You can find some of her fiction, weird and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.