Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches.

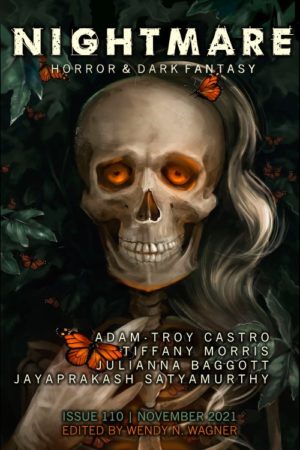

This week, we cover Nelly Geraldine García-Rosas’ “Still Life With Vial of Blood,” first published in the September 2021 issue of Nightmare Magazine. Spoilers ahead. Lots of spoilers, as the story is itself barely longer than the summary—we recommend going and reading it for yourself. CW for suicide and acid attacks.

“I love gloomy days, but not gloomy fire days. The sky is made of smoke.”

The story is subtitled “Brief Notes on the Art of Juan Cavendra.” The unnamed note-writer seems to be a professor of art, perhaps a curator (let’s call them that)–in any case, they’ve been studying Cavendra’s work for years. Despite this familiarity, they can’t name the “something” in Cavendra that makes them simultaneously want to close their eyes and to keep them wide open to “grasp the vastness” that is his signature. To their remarks, the curator appends curious footnotes that I’ll describe in square brackets next to the footnoted word or paragraph.

The one thing the curator feels “comfortable” in asserting [Footnote 1: The curator does not feel comfortable] is that Cavendra’s art is of an “utmost beauty” that paralyzes the viewer [Footnote 2: The curator is literally paralyzed. They can’t move, or don’t want to] and confronts them with thoughts of personal extinction. It’s a beauty at once joyful and agonizing and not to be grasped by the rational mind.

The first work the curator addresses is “The Sky is Made of Smoke” from the Fire series (1984). It’s a very large oil on canvas painting (16 by 23.5 feet), one of six the artist executed after refusing to evacuate his wildfire-threatened home. Sepia smoke and ruby flames erupt out of the canvas, dancing; from the heart of the conflagration crawls a single figure so “black it almost shines like a dark, victorious sun.” [Footnote 3: No, in fact the figure doesn’t so much emit light as it makes the curator feel they’re going blind, and yet to look away is entering a sudden winter of cold gray light.]

[Footnote 4: This painting’s only two owners died in fires, one deemed accidental, the other arson. The “arsonist” owner left a suicide note stating “This is the diary of my scorched life. From flames I come. In flames I go. Look at them dance.”]

The second work addressed is “They Sound Like Rain” (1999), comprised of seven unnumbered lithographs, the artist’s proofs. The prints almost look like seven copies of the same lithograph, showing a bony human face [Footnote 5: That’s not human.]. The more acute viewer will see in the figure’s eyes “the small figures, the shimmering eyes inside the eyes, the legion that lies in there.” [Footnote 6: “They’re coming. They won’t stop.”]

The prints of “They Sound Like Rain” are indeed like raindrops, the curator opines, similar yet unique, “a treat for the imagination.”

[Footnote 7: The seven prints have been separated since their making. Each owner has succumbed to the same “whim” of throwing acid into the face of a family member, and each victim has lost one eye.]

Buy the Book

And Then I Woke Up

The third work (2020) is untitled and unsigned. It is “Sanguine on human skin,” of “Variable size.” The curator explains that the “difficulty of conservation for the peculiar technique used in this piece of art” prevents accurate measurement. Sometimes the piece looks about five inches wide, sometimes as much as a meter. Curator calls it “Still Life with Vial of Blood,” though it contains no such vial. Instead it depicts a pile of human remains similar in proportion to Cavendra’s body as shown in the self-portrait photo series called “Diary of My Scorched Life.”

[Footnote 8: “Diary” is a series of hundreds of photos showing Cavendra naked, bound and bloody in a dim-lit room. Tiny dark figures advance from the background toward the camera. Cavendra looks uncomfortable. He doesn’t dare move.]

Cavendra disappeared after producing this amazing piece of art, his best but not his last, the curator hopes.

[Footnote 9: Curator writes: “He didn’t go away forever. He’s there. He’s that thing. He’s coming, too, from the flames. Look at him dance.”

What’s Cyclopean: The figure in The Sky is Made of Smoke “is so black, it almost shines like a dark, victorious sun.” Unless it isn’t, unless it’s “like going blind, like falling into an infinite well I will never stop falling into.”

The Degenerate Dutch: No degeneracy this week.

Weirdbuilding: Another contribution to the Weird Art gallery along with Pickman’s portfolio, Black Stars on Canvas, and Crispin’s portraits.

Libronomicon: What kind of document is this, even?

Madness Takes Its Toll: Cavendra’s pieces leave suicide and acid attacks in their wake.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

After reading this marvelously disturbing piece, I have a disturbing question: Who the hell is the narrator? Lot 3 has had two non-Cavendra owners, both dead. Lot 4 has been owned by several people, and consists of seven prints that have never been brought together since their creation. Lot 13 appears to be generally available for viewing if a challenge to conserve. So who (other than Cavendra, referred to in the third person and currently undergoing a fate worse than death) is in a position to see and comment on them all?

Narrator describes “years of close study,” which they’ve somehow survived. Are they an art critic with enough cache to get into private collections? A grad student with a really unfortunate choice of thesis topic? A collector or agent for collectors, like the seekers of hazardous books in A Fractured Atlas? A curator, as Anne suggests in the summary? Whoever they are, their attraction/repulsion is growing, and some sort of trap seems about to close around them.

The footnotes here remind me of Sarah Gailey’s “Stet” and Sarah Pinsker’s “Where Oaken Hearts Do Gather,” both of which use scholarly footnotes to tell a not-so-scholarly story. With García-Rosas, though, I’m less certain that the footnotes are showing up anywhere other than in the narrator’s head. They seem to argue with the main text, with the placating descriptions of Cavendra’s work as ordinary art. No, I’m not comfortable. Yes, I can’t move, or maybe I could move if only I wanted to, but I don’t. That’s not human.

Maybe something is making them write the main text—perhaps the same thing that destroyed other patrons of Cavendra’s art, and is transforming or working through Cavendra himself. Those small figures filling the eyes of that bony face, and surrounding Cavendra in Diary of My Scorched Life. Maybe something came to him in the wildfire. In their natural role, such fires burn away overgrowth to allow new types of plants to thrive—amid modern building patterns and magnified by climate change, the transformation is catastrophic. Maybe something less natural came through the flames that does the same thing to human minds.

I’m considering, uncomfortably, cordyceps mushrooms as a model for the effect of eldritch art. The King in Yellow comes close, warping the minds of readers to create a world of its choosing. So does Margaret Irwin’s unnamed Book. García-Rosas’ form is extraordinarily succinct in depicting someone in the moment of conflict between what the art would make of them, and their horror at what’s being made.

“Still Life With Vial of Blood” is a quick sketch that leaves the reader with at least as many questions as answers—questions that we might not want to have addressed. A treat for the imagination!

Anne’s Commentary

Many have argued that all works of art resist summary–what the work is and means can only be expressed by the work itself, in its entirety, word by word, musical note by musical note, brushstroke or chisel chip by brushstroke or chisel chip. In the case of “Still Life With Vial of Blood,” you could read the story about as quickly as my attempt to describe it. The story is 1000 words long, the summary 617.

In this series, I’ve occasionally tackled summarizing poetry. It’s a disheartening task because, of all literary forms, the poem is most emphatically what it is, word by word. The nearer a prose piece approaches this state of stubborn being, the more akin it is to poetry. For me, “Still Life” falls in the middle of the prose-to-poetry spectrum. In their notes on Cavendra, García-Rosas’ “curator” strives to maintain an academic distance from the subject, down to the inclusion of footnotes. Ironically, it’s in the footnotes that the curator slips away from self-protective professionalism to raw reaction–in effect, from sanity toward madness.

If by madness, that is, we mean a mind-blasting recognition of the truth lurking beneath the reality.

Art can be a dangerous pursuit for the creator, its appreciation a dangerous pursuit for the student or connoisseur. Look at Connolly’s Fractured Atlas (um, no, you look at it.) Occult tomes in general exude a perilous allure. The King in Yellow and a certain yellow wallpaper could mess up even the casual reader or resident. Pickman’s paintings instilled lasting phobia in at least one viewer. Erich Zann’s music carried him off in the end, or rather Erich’s biggest fan did. If you’re going to dive into art either as maker or consumer, maybe you better stick to its shallower waters, the ones lapping the shoreline of consciousness and introspection. Actually, skip introspection altogether. The deeper you plunge, the more monsters you’ll encounter, and down in the abyssopelagic zone of “utmost beauty” are some eager to devour you.

So paint kittens with balls of yarn. Sculpt simpering nymphs and polite satyrs. Compose or write in a safely formulaic vein. Though… where’s the glory in that? You want glory, don’t you? Even if it couples joy with agony? Even if it paralyzes and confronts you with thoughts of your own extinction? Even if utmost beauty can only be processed by an irrational mind?

García-Rosas ingeniously structures “Still Life” as a set of critical notes followed by footnotes. The superscript footnote numbers instantly jump you to the corresponding footnote texts, but you needn’t click those links. You can instead read straight through the main text, then straight through the footnotes. The second option’s the one I took, because skipping immediate referral to footnotes is my usual modus operandi. Your experience of this story will be significantly different depending on how you read it.

Their footnotes ignored, the curator comes across as an academic sound in mind and critical judgment. Cavendra comes across as eccentric, but in an acceptably “artistic” way rather than a malevolent one. Things slope into weirdness when the curator considers that unnamed third work, blood on skin, of variable proportions. Yet their tone remains matter-of-fact.

Reading the footnotes last will radically change your perceptions. You’ll realize that the curator’s calm professionalism has been a false front all along. They are comfortable discussing Cavendra? No, they’re not comfortable at all. They’re merely waxing metaphorical in writing that the beauty of Cavendra’s work paralyzes them? No, either they’re physically unable to move or their immobility is psychosomatic, neurotic. The figure in Cavendra’s “Sky is Made of Smoke” “shines like a dark, victorious sun,” a simile that suggests exaltation in both figure and viewer, yes? No, the curator’s response is far more complex. The figure blackens their vision like a plunge into an infinitely deep well, surely a terrifying sensation, but one packing such a visceral charge that to look away numbs and depresses the curator like a “sudden winter.” Regarding “They Sound Like Rain,” Calm Curator writes that the lithograph features a “bony human face.” Footnote Curator blurts, “That’s not human. That’s not human. That’s not human.” Calm Curator writes there’s a “legion” in the bony face’s eyes. For me this recalls the demon’s response to Jesus that “My name is Legion, because there are many of us.” Footnote Curator may recall the same scripture, fearfully adding “They’re coming. They won’t stop.”

Footnotes 4 and 7 depart from near-hagiography to throw a sinister light on Cavendra’s work. The only two owners of “The Sky is Made of Smoke” died in fires. One victim set the fire himself, leaving a suicide note proclaiming “This is the diary of my scorched life.” Could it be mere coincidence that Cavendra’s series of photographic self-portraits is titled Diary of My Scorched Life? Owners of the lithograph proofs in the “They Sound Like Rain” series each committed the bizarre act of disfiguring a family member with acid–and each family member lost an eye in the attack. Coincidence? Smacks more of a curse.

Footnote 8 throws the sinister light on Cavendra himself. It describes the hundreds of photos collected as that “scorched life” Diary, in which he’s bound naked and bloody against a background of tiny dark figures advancing on the camera. Lurid, to say the least. Beyond eccentric. It’s interesting that the curator thinks Cavendra looks uncomfortable and unable to move–in earlier footnotes, it’s the curator who’s uncomfortable and paralyzed.

If you read the footnotes in conjunction with the main text, you’ll know all along that beneath the scholarly equilibrium of the curator’s “brief notes” is the mix of terror and exhilaration accounted for by Footnote 9. Its four lines deal in reverse order with the three works described. “He’s coming, too, from the flames/Look at him dance” equates the black figure of “The Sky Was Made of Smoke” with life-scorched Cavendra himself. “He’s there. He’s that thing” equates Cavendra with the inhuman face of “They Sound Like Rain.” Finally there’s the untitled anomaly the curator calls “Still Life With Vial of Blood.” It’s a leap of faith for the curator to write “He didn’t go away forever” when it’s probable those anatomically correct body parts look like Cavendra’s because somehow they are Cavendra’s, depicted on his own human skin with his own blood.

Such a death, coupled with hundreds of lesser bloodlettings photographically captured and a few art buyers sacrificed via the malign influence of their purchases, might be the price the artist had to pay for the immortality that is utmost beauty.

We’ll be away next week due to family obligations. After that, we’ll continue P. Djèlí Clark’s Ring Shout with Chapters 3-4.

Ruthanna Emrys’ A Half-Built Garden comes out in July 2022. She is also the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her short story collection, Imperfect Commentaries, is available from Lethe Press. You can find some of her fiction, weird and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.