The Black Phone was pretty much made in a lab for me. Between the retro setting, the violent, foul-mouthed kids, the objectively real presence of the supernatural, the fraught family dynamics, Ethan Hawke—it’d be weird if I didn’t like it. That’s why it makes me extra happy to say that The Black Phone genuinely creeped me out.

I seem to be un-scare-able. Hereditary didn’t phase me, I love The Evil Dead, I’ve written already about my fondness for Poltergeist, I’ve seen The Exorcist 167 times, and it keeps getting funnier every single time I see it.

Which is why I was surprised at myself when I needed to pause The Black Phone. More than once.

Is it me? Am I getting… soft?

I had to mull over this one a little bit while I wrote this essay, but I think what got me was that the horror in The Black Phone is human. It’s real people doing horrible things to other real people who can’t really protect themselves, not ghosts climbing out of TV sets or hapless teens reading from clearly cursed books. There was no point where I could yell, “Don’t go in there, you idiot!” because I would have been yelling at helpless children who were the victims of circumstance and bad parenting.

In order to talk about this movie in any depth I’m going to have to delve into spoiler territory, so I’ll cover some basics and then warn anyone who hasn’t seen the movie yet to dip out.

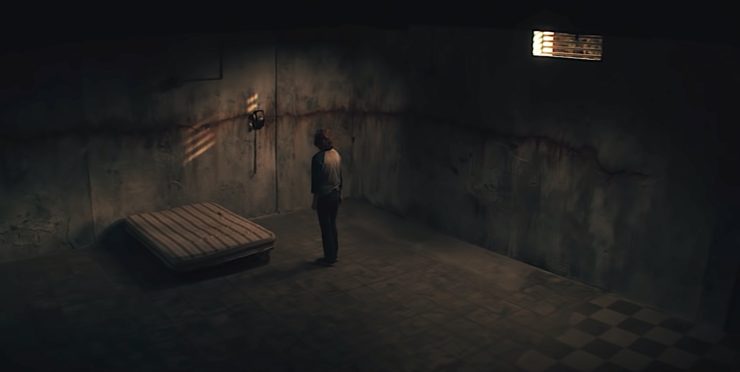

First of all, this movie worked on me, as I’ve said. The Black Phone is an adaptation of a very creepy story by Joe Hill, part of his masterful collection 20th Century Ghosts. I think it’s a solid work of slightly grimy, ’70s-esque horror—easier to watch than and of the true exploitation of that decade, but a little rougher than Sinister, Scott Derrickson’s previous collaboration with Ethan Hawke. The plot is spare to the point of seeming almost comic: kids are getting snatched off the streets of Denver by a man called The Grabber. We follow one such kid, Finn, as he tries to stay alive in The Grabber’s soundproofed basement.

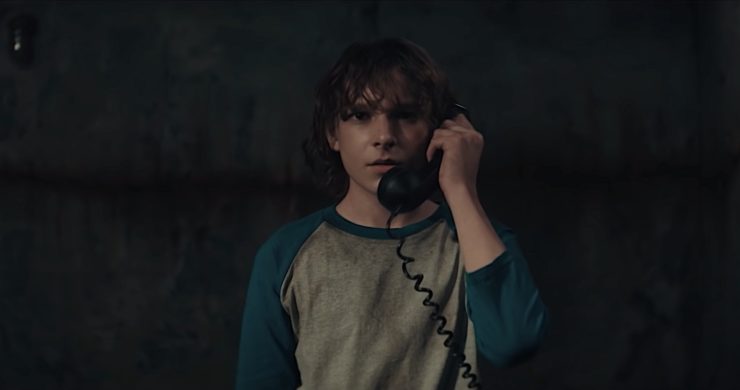

The performances are uniformly excellent. Most important, the kids are all amazing. Mason Thames has to carry a lot of the movie as Finn Blake—he spends a lot of the runtime alone in the basement either processing what’s happening to him or listening to ghosts, and he’s heartbreakingly believable as a kid who thinks his life is over. Likewise Madeleine McGraw has to create a fine balance as his sister Gwen—her pugnacious, I-take-no-bullshit reactions to bullies and cops are hilarious, but then she has to inhabit the fear and vulnerability she feels around her powderkeg of a father. It’s fascinating to watch her tiptoe around the house trying not to set him off and then transform into the kind of girl who brings a rock to a fistfight once she’s safely outside. Jeremy Davies (my beloved) does an excellent job as the brooding, melancholic father, Terrence Blake, who occasionally explodes into violence. So good, in fact, that I hesitated before typing the customary “my beloved” suffix after his name, because he is son of a bitch in this movie. But once Peter Bernardone, always Peter Bernardone.

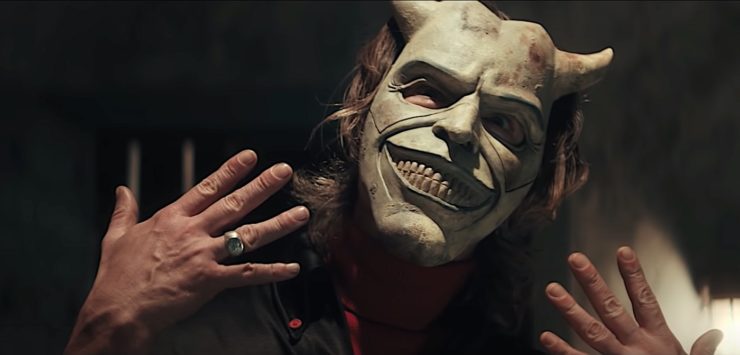

I’ve seen some critics say that Ethan Hawke doesn’t do enough as the Grabber, but I don’t think he needs to. This isn’t some complicated psychopath with a backstory. He’s not Hannibal, he’s not The Candyman, he’s not a symbol of some larger societal problem—he’s a fucking child murderer. Sometimes a child murderer is just a child murderer, and sometimes we can have a villain to simply root against, as a treat. And for this, Hawke is perfect. He speaks in a lilting voice, he sounds delighted when he tells Finn he’s never leaving the basement again. When he brings Finn eggs, and the boy demands to know what’s in them, The Grabber sounds baffled when he says “salt and pepper”, and then answers Finn’s real question with terrifying finality: Why would he want to poison the boy when he already has him?

The Black Phone opens with a baseball game that establishes Finn as a kid with a strong arm, who seems kind of isolated—it’s the batter he almost strikes out who compliments his pitches, not his own teammates—before cutting to the batter, Bruce Yamada, riding his bike through town to the sweet sound of Edgar Winter Group’s “Free Ride”. I could only read this as a nod to the ’70s teen epic Dazed and Confused—but then everything veers into a terrifying direction. Bruce is kidnapped by The Grabber, and Finn spends the next 20 minutes not dodging comically violent seniors in a hazing ritual, but rather bullies his own age who attack without warning and want to draw real blood.

This version of the ’70s seems maybe a bit more accurate than Richard Linklater’s warmer, fuzzier one: the adult world and the kid world are absolutely set apart. Teachers are never around when the bullies attack; parents are alien, violent, their rule absolute—if they beat the shit out of you there’s no recourse. Racial slurs are thrown around without a first thought, let alone a second (I have to assume that Bruce took that name as a path of least resistance in the face of late-70s white America), and boys and girls exist in separate spheres.

The tone is perfect. “Missing” posters hang on every fence, but the adults are clearly trying to ignore the evil in their midst. Kids still have to come to school, there’s no sense that there’s been any sort of buddy system or neighborhood watch instituted, no curfew. The Grabber’s black van stalks through the streets like Jaws at a particularly crowded summer beach. The kids, of course, have developed a mythology around all of this: if you talk about The Grabber, say his name aloud, you’ll be the next to disappear. Which also serves the purpose of keeping people from talking about him openly and protecting themselves.

Now here’s where this story gets interesting, at least to me, and this is where I’ll have to talk about potentially spoiler-y stuff, so if you want to go in cold, here’s where you should click away.

This could have been a purely psychological horror—kidnapper takes kid, kid tries to escape, we check in with the families and friends occasionally. The Grabber, for all that he’s mythologized by the kids, is human. He’s able to overpower even strong kids because he’s a large-ish adult man, he’s scary because he wears a scary mask. But there is a supernatural element, and it’s entirely benevolent. Or really, there are two supernatural elements.

First, Gwen, like her mother, is subject to dreams that turn out to be real. Sometimes they’re extremely literal, sometimes oblique, she has no control of them. She can’t will herself to have them. The dreams seem to show her dark things. And yet, while the family does not seem religious—there are hints that her father is actively against religion, just as he’s against the idea that his late wife was psychic—Gwen believes that Jesus is the one sending the dreams. She even tries to conjure the dreams via a patched together ritual with rosaries and pocket New Testaments she has stashed in her room. So even though the dreams themselves are sometimes horrific, she thinks they’re coming from a well-meaning source.

Then there’s the titular phone. Is there anything more innately terrifying than a piece of technology that works when it shouldn’t? We see that the phone’s cord is cut. It’s not connected to anything. So how the fuck is it ringing? And the first time we’re as freaked out by it as Finn. But once he picks up the phone, the voice on the end isn’t some ghost tormenting him, it’s the friendly, somewhat baffled voice of Bruce Yamada, complimenting his pitching arm and trying to help him escape. From then on the phone is a source of comfort, even when the voice on the other end is angry or violent, as two of the ghosts are. Only one of the ghosts was ever really friends with Finn in life, but in death they’re all united in trying to save him—and, if at all possible, get revenge on The Grabber.

The supernatural, frightening though it may be, is here to help. The horror in this horror movie is wholly human. Because the other interesting element, I thought, was how much The Grabber acts as a mirror to Finn and Gwen’s father.

The Grabber’s violence is almost entirely implied. We know he killed other kids, and in the end we see more violence, but he really doesn’t do much during the movie, Two separate time he leaves the door to his dungeon unlocked, and then lies in wait to see if Finn will try to escape. Finn’s only saved the first time by a well-timed phone call warning him that if he ventures up the stairs The Grabber will beat him mercilessly—he’s trying to trick Finn into a game he calls “Naughty Boy”. Taking the bait of the unlocked door will mean that Finn is being “bad”, and The Grabber will punish him before throwing him back in the dungeon. According to one of the ghosts, “Naughty Boy” is the first step in The Grabber’s pattern, which ends in murder, and Finn’s refusal to take the bait will keep him alive longer as The Grabber won’t want to break his routine. Obviously, this is incredibly disturbing.

But, what is this sick game other than an amplified version of the life Finn and his sister already live? Their father drinks constantly when he’s home. When he inevitably passes out in his recliner it’s on one of the kids to silently take his beer bottles away, turn the lights off, pull the needle from the record spinning in the record player. Clearly there’s hell to pay if they wake him. In the mornings they have to tiptoe silently through the house lest they run afoul of his hangover—a practice that, horrifyingly, serves Finn well in his initial escape attempt. And the one act of true, abject violence we actually see onscreen isn’t The Grabber at all, but their dad beating the crap out of poor Gwen because she had one of her dreams. The idea that she might be turning out like her mother throws him into a merciless rage, and he doesn’t care about her cries of pain, Finn begging him to stop, nothing. The two kids are trapped in a labyrinth of inscrutable rules. Their father has created a situation where they can’t help but fail as he holds the threat of terrible pain over their heads.

So when we see The Grabber sitting in his chair, waiting for Finn with a belt across his knees, who else can we possibly think of?

Terrence offers no comfort to Gwen in her brother’s absence—the only relief she gets is in the terrifying dreams that might lead her to him. And one of the most intense scenes in the film is her attempt to tell her father what she’s seeing, when we all know her father might snap and brutalize her again.

This to me was the most interesting thread in the film. The Black Phone is a horror film where the voices of the dead and terrifying dreams are signs of hope and mercy, while real, flesh-and-blood humans are the authors of dread and terror.

Leah Schnelbach can’t really express how happy they are to be living through this era of thoughtful horror. Come bring them messages of doom on the haunted communication system that is Twitter!