I keep thinking about Dan Torrance’s room.

I was surprised by Doctor Sleep, the sequel to The Shining, when it came out in 2019. As a fan of Mike Flanagan, I expected a solid work of horror, maybe with a little more emphasis on grief than one might expect. But I was still startled and extremely pleased by how willing he was to make a movie that was somehow both an epic, decade-spanning work of horror, and an intimate story of addiction. (Also I owe everyone an apology—I reread my original review of the movie and said, and this is verbatim: “despite the ghosts and mystical trappings, Doctor Sleep is not a horror movie.” What, Past Leah? What the hell were you talking about, yes it is so a horror movie! Anyway, sorry, the rest of the review is pretty good.)

Since I try to watch even more than my usual amount of horror in October, I decided to watch The Shining and Doctor Sleep back-to-back, and came away liking the sequel even more than I did three years ago.

I usually watch The Shining at least once a year. I love it. I can’t even remember the first time I saw it—definitely before I was 10—and it’s kind of a comfort watch for me. I love the ambiguity of the ghosts, the way nothing’s ever nailed down, the conspiracy theories, the way it’s an incredibly accurate depiction of domestic violence. (And yes, it’s gotten harder to watch knowing that Shelley Duvall’s life on set was hell, but also I appreciate her titanic performance more each time I see it.) But most of all what I love about it is that, when I was a little older than Danny Torrance, I also lived in a hotel. My dad managed the place, my mom bartended, I did my homework at the bar drinking Tom Collins mix and slamming shots of Pepsi in imitation of the guys who came in for Happy Hour. Once they were a little, uhhh, relaxed, I’d hit ‘em with my stand-up routines until my mom made me leave. It’s weirdly (very weirdly) homesickness/joy-inducing to watch Danny run rampant through The Overlook on his trike, playing in a different hallway each day, watching TV in one corner of a giant, echoing event space. (A TV that isn’t plugged in and can’t possibly be broadcasting, but whatever.)

Rewatching the movie this time brought a cascade of Pandemic Emotion, as I related possibly a little too hard to Wendy trapped inside during a winter that seemingly has no end—or at least, not an end you want to think about. And I related definitely too hard to Jack, staring at a manuscript that refuses to finish itself. (All these ghosts but there are no ghostwriters? All these bartenders and caretakers, but not a single revenant with a plot idea they’d like to share?) Each year I notice different things, and this time, knowing I was going to hit play on the sequel later that night, I tried to focus especially on Danny’s experience of the Overlook, and to put myself in the mind of a five-year old living through that.

We hear about Jack Torrance’s alcoholism, and that he stopped and told Wendy she could leave him if he started drinking again. And we see that even at the opening of the film Jack is wound tighter than an Omega as he drives the family to the Overlook, and we can hear, in all of Wendy’s ooh-ing and aah-ing over the hotel, the desperate hope for a fresh start. We don’t see his alcoholism. We see Wendy’s haunted eyes and false cheer, and how even early in their stay at the Overlook Wendy and Danny tiptoe around him. And then, we see him go completely off the rails on ghost alcohol after he quite literally sells his soul for a drink. But is that alcoholism or possession? Is it him chasing Danny and waving an axe around, or the spirit of the hotel itself?

Going straight from The Shining’s closing scenes into Doctor Sleep is a fascinating experience.

Immediately after the tragic events at the Overlook, Dan Torrance is a boy so traumatized he can only talk to ghosts. And when we skip ahead to his life as a barely functioning alcoholic, it makes sense really. Where his dad seemingly drank too much to dull his frustrations with his homelife, his teaching job, and his lack of success as a writer, Dan drinks to keep the ghosts at bay. He doesn’t fall into the Raymond Carver territory of his dad’s domestic savagery, oh no—Dan gets titanically drunk, fights a dude at a bar, adds a frisson of coke to the booze, and then abandons his date passed out (and possibly OD’ing) in her own puke, but not until after he plants her crying toddler on the bed next to her.

What’s great about this is that it shows us Dan’s trauma and its aftermath, without over-explaining it. It shows us that Dan, who would never consciously terrorize anyone the way his father terrorized him and his mother, has become capable of terrible acts of his own. These scenes are especially potent if you’ve just come from The Shining. Seeing little moppet Danny Torrance all grown up and rifling through his hook-up’s wallet for cash while a new moppet cries from the other room is an elegant example of “real life horror”.

But there’s more! This is a ghost story, after all. Dick Halloran materializes and does his best to shame Dan into leaving the money for the woman’s kid, if nothing else. Dan explains that technically, this is his money anyway, because she stole his to buy the coke. Rationalizing your terrible choices to the ghost of the man your dad murdered? As rock bottoms go, this one’s fucking impressive. Dan splits with the cash, Dick mournfully says “Doc…” and it—well, I’ll just say it: it hit me like an axe to the chest.

I think about this scene a lot. Especially on this watch, as I hit play a few minutes after finishing The Shining. Flanagan opens his film with a scene of Rose the Hat capturing a little girl named Violet. Showing us an innocent girl stumbling off the path, wide-eyed as a fawn, creates a dark fairy tale vibe that is worlds away from Kubrick’s icy directorial stare. (And giving us a fun Frankenstein homage is a nice update to Kubrick’s own riffs on The Omen.) Having established that this is a real horror film, in which kids die horribly, Flanagan drops us into the slight uncanny valley of Alex Essoe, Roger Dale Floyd, and Carl Lumbly playing Wendy Torrance, Danny Torrance, and Dick Halloran—an uncanny valley that’s made a little deeper if you’ve just seen the other film. When Flanagan bounces us through those two very different tones, only to cut to a scene that feels like a Trainspotting outtake, it makes the realism of Dan’s lowest point even harsher.

Which makes it all the better when, in the midst of this really good, really brutal horror movie (seriously, Past Me), Danny’s story becomes an equally realistic story of clawing your way out of addiction.

Dan gets lucky: he makes it to New Hampshire; he runs into Billy; a landlady’s willing to take a chance on him; a doctor offers him a steady gig.

Dan works his ass off: when he has a vision of his one-night-stand and her dead child, he instinctively looks toward the bottle he brought with him, and no one could possibly fault him for drinking that horror away—but instead he runs to Billy for help; he shows up to meetings; when his Shine gives him a way to help people he uses it immediately and selflessly. When he earns his 8-year chip he dedicates it to his dad.

Jack Torrance was a caretaker. He was a teacher who wanted to write novels as well. He ended up being a caretaker for a hotel he never could’ve afforded to stay in. Wendy’s aforementioned ooh-ing and aah-ing may be her attempt to clinch the job for her struggling husband, but it’s also the reaction of a rube, staggering gawp-mouthed through rooms she wouldn’t be allowed inside in any capacity beyond “the help.” In the book Jack’s role as a caretaker is much more pronounced, as the tension of the book comes from him trying to keep madness at bay out of love for Danny, and in the end he’s able to let the boy escape. But in the film, it’s all Wendy.

Jack aligns himself with Ullmann, the manager. He keeps up an act that he wants the job not because he’s desperate for money, but because it’ll be ideal for his writing project. He emphasizes his real career as a writer, not a mere teacher or caretaker. When Wendy and Danny come back with him, He holds himself casually, doesn’t respond to Wendy’s enthusiasm, and seems as much as he can to be acting as though he’s above the job, in a subtle alliance with Ullman, the boss, against his wife, kid, and eventually Dick Halloran.

Dick, meanwhile, immediately allies with Wendy and Danny. He takes Wendy on the kitchen tour, shows her the food like a dragon showing off a hoard of treasure, and repeatedly reassures her that, while the industrial kitchen is big, it’s still just a kitchen—she’ll get the hang of it. Then he offers Danny ice cream so he can gauge the boy’s powers and warn him about the hotel. The Black man, who’s a cook, not management, spots the vulnerable people right away, and moves to be supportive and nurturing to them. And indeed, later we see that it’s Wendy who’s not only doing all the cooking and making time for Danny, she’s the one tending the boilers, not Jack. She’s the one acting as caretaker both to her family, and to the hotel itself. It’s Dick who comes back and saves them, both directly in the novel, and by providing a posthumous Sno-cat in the movie.

And in Doctor Sleep we see that Wendy will do literally anything to protect her son—even move to Florida.

And this becomes one of the strongest aspects of Doctor Sleep. Dan’s not a writer, like so many King heroes before him, or a lawyer, or, in fact, a doctor. He doesn’t use his powerful psychic gift to con people. The one time we see it benefit him is an accident—he tells a fellow AA member where to find his misplaced watch, and the man, Dr. John Dalton, offers him a job: a good turn rewarded. But not until a fascinating conversation cum job interview that is, I think, the crux of the whole film.

Dalton’s office is an exact replica of Stuart Ullman’s office in The Shining. So if you’ve seen the earlier film (or maybe more so, if you’ve seen Room 237 which makes a convincing case that that room cannot fucking exist) it’s possible that the hairs on your neck are already standing up when the scene begins. But it veers in a much more interesting direction than just mirroring Jack’s job interview. Doctor John asks Dan of he’s a churchgoer, and Dan ask if that matters. When the man walks it back a bit, to try to ask Dan if he believes “in something bigger” Dan shorts that out, too: “Our beliefs don’t make us better people. Our actions make us better people.”

And what’s the job? Working at a hospice. After telling Dr. Dalton “We’re all dying. The world’s just one big hospice with fresh air” Dan becomes an orderly—he cleans the place, minds the front desk, and most likely helps tend and store people’s bodies before they’re given over to a funeral home.

So Dan is: a janitor; a receptionist; a nurse. Specifically a hospice nurse. These are jobs that are overwhelmingly done by women in this society. Overwhelmingly underpaid, under-appreciated, and devalued. His life reflects both the pay and the tenuous grasp on a lower rung of society. Even after eight years at the job he lives in a single, sparsely furnished attic room that his friend Billy helped him get. He has few possessions, just the furniture the room came with and a serviceable car. He seems to change between scrubs and plain outfits of sweaters and jeans. There is no partner, no kids, no mention of a nest egg or a plan to go back to school or any sign of “upward mobility” under capitalism. He’s living his life in his room, he helps out at Teeny Town on his days off, and he reads.

Because then his true job becomes sitting with people as they die. What his “actions” consist of, for the most part, is taking on a role that would send most people away screaming down the hospice hallway.

Later, when a kid asks him for help (shattering his small room with word REDRUM) he upends this simple, astonishing life he’s built to help her. He goes back to his worst nightmares to make sure she doesn’t end up like him.

I fear that I’ve done that thing I do, where I talk and talk and talk about a movie I like and suck the fun all out of it. Doctor Sleep is fun! Rebecca Ferguson’s performance is extraordinary. The scene where the True Knot captures and tortures Jacob Tremblay is legitimately one of the most chilling scenes in a horror movie in this century. Abra is such a compelling young hero, and her battles with Rose the Hat are worth the price of admission. The car crash scene, holy shit! The connections to the Dark Tower, aaahhh!!! And I seem to be one of the few critics who didn’t mind the return to the Overlook. I can see how it became a bit fan service-y, but honestly I think the only problem with it is that, in this very long film, it was a bit rushed. I wanted to spend more time with Dan wrestling with his past before the big showdown, I think? (If I went back to my old hotel it would take me a lot longer to come to terms with it, and it was nowhere near as haunted as the Overlook.)

But the reason I’ve keep thinking about Doctor Sleep for the three years since I reviewed it the first time is really tangled up in how I feel about Dan Torrance and his room.

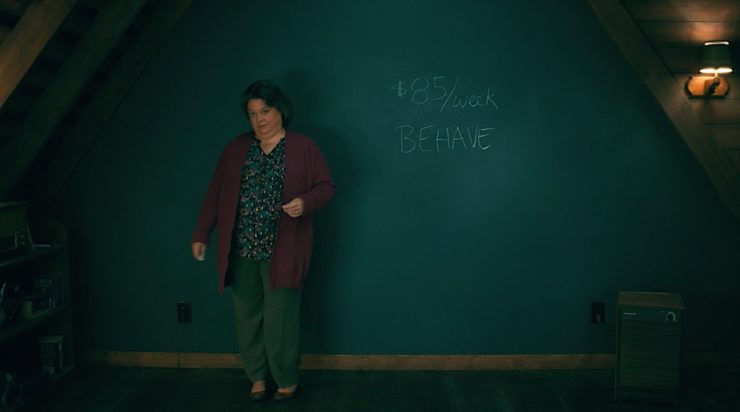

Thinking about the path of his life in that room. When he moves in, his landlady was hostile and caustic. She speaks witheringly of the math student who used to live there, and then uses his chalkboard wall to write the rent along with the word “BEHAVE” like a bitchy substitute teacher glaring at an unruly class.

On his first night in his new apartment he has a horrifying nightmare. Or, let’s be real, his Shine wakes up as the alcohol leaves his blood, and gives him a vision. He feels an arm around him in bed, and when he looks back there’s his date from the other night, whispering “They haven’t found us yet. They were used to hearing him cry because I left him alone so much. So they haven’t found us yet.” And when he looks down—of course he looks down—there’s the blank dead face of the baby he abandoned.

But he doesn’t run this time.

I keep thinking about the apartment in The Shining, the place in Boulder where Danny lived with his parents Before. It was small but bright and full of books. Books stacked on every shelf. And in their apartment in The Overlook, again, books spill from every corner. (This is the weirdness of life in a hotel: they have this whole opulent hotel to care for, but only one corner of it is really theirs. But at the same time, in another way, they get to run amok in a castle. When we lived in our hotel we knew it was only for short time. Like all the other guests, we would, eventually, check out. But then when we moved back into a house that, too, felt like a temporary situation, and it took months to shake that feeling off.) When we check back in with Dan, right before the films threads start to knot together, we see that he hasn’t even bothered to buy new furniture. This monk’s cell existence—no TV, even, but books piled up on every flat surface.

And now he wakes up to smiley-faced messages from a kid who shares his gift.

As often happens, I’m circling the thing I want to say without finding a way to say it. I’m not sure this is a thing that can be put into words. It’s something about the gap between the story’s title, Doctor Sleep, in which the doctor is actually a janitor who can provide a service that the official doctors can’t. It’s something about living in the opulence of The Overlook and finding evil there, and then living in a single room, helping people die, choosing not to drink each day Something about how the life he’s built in this room is shattered—ended—by the same desperate message he sent as a child. Something about the mirroring in how Dan treats Abra as an equal rather than a little kid, the same way Dick Halloran treated him. How rare it is to get a male character like Dan, and what a beautiful reply he makes to Jack Torrance. The way the movie makes time for Dan to stand up at an AA meeting and dedicate his chip to his father, and the way he refuses to take a drink in the Gold Room’s bar. All the tiny actions that turn him into a real hero without ever undercutting the fact that he is, truly, a caretaker.