Welcome to Close Reads! In this series, Leah Schnelbach and guest authors dig into the tiny, weird moments of pop culture—from books to theme songs to viral internet hits—that have burrowed into our minds. This time out, Sarah McCarry teases out similarities in the mythmaking of noted racism enthusiast H.P. Lovecraft, and noted purveyor of ’90s teen chillers, Christopher Pike.

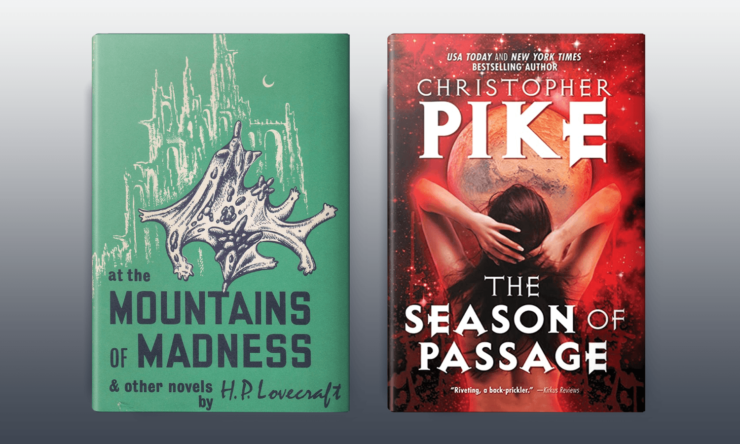

You probably haven’t spent a lot of time considering the striking similarities between HP Lovecraft’s classic 1931 Antarctic travel warning At the Mountains of Madness and Christopher Pike’s extraordinary 1992 Martian-mission-from-hell bonanza The Season of Passage, if for no other reason than the fact that you probably haven’t read The Season of Passage. In thinking about this essay, I did consider the possibility that the Venn overlap between “people who are enthusiastic about At the Mountains of Madness” and “people who cannot shut up about The Season of Passage” consists entirely of, well, me. And yet! dear and patient reader, I ask you to join me, on a journey that will carry us from the frigid, lizard-vampire riddled plains of Mars to the frigid, lizard-ish-vampire-ish-infested mountains of Antarctica, from wet monsters to dry monsters to comely young ladies frolicking about spaceships in their undershorts; in short, a very specific window into the more dubious corners of the American psyche.

Are you ready? Let’s go.

The Christopher Pike Leading Lady is a curious figure: whether she is a ghost solving her own murder (Remember Me), attending a festive ski weekend with homicidal siblings in disguise (Slumber Party), or trying to prove her innocence after her best friend has framed her for murder at the behest of a sociopathic gardener (Fall Into Darkness), she is almost uniformly hot but insecure, sensible but not too smart, unaware of the (powerful, obviously) effect she has on the opposite sex, unambitious, unthreatening, and disinclined toward supportive undergarments.

In Pike’s 1992 horror novel for adults, The Season of Passage, she is Dr. Lauren Wagner, a physician-astronaut who we meet breasting boobily on a treadmill in the novel’s early pages to the delight of Terry Hayes, a reporter sent to interview her. What exactly she is a doctor of is never entirely clear. At one point in the novel, she gives a lethally dehydrated fellow astronaut wine to revive him, so we can presume she is not a nutritionist. (To be clear, I love this book.)

The plot of The Season of Passage is difficult to summarize with any brevity. In 2002, two years before the novel opens, a manned Russian expedition landed on Mars, sending back scenic footage and chipper communiqués until abruptly ceasing all contact a month later. Lauren is entrusted with the health of the NASA mission sent to Mars to investigate their disappearance, although even her now-fiancé Terry, a humble freelance journalist and writer of lurid thrillers in his spare time who even the most generous reader will have trouble separating from the author of Season of Passage himself, reports to the reader that he suspects she was selected more for her comeliness than her intellect. (Lauren’s behavior throughout the novel does rather seem to confirm this hypothesis, although the rest of the crew does not come off as much smarter.)

Once the crew gets to Mars, they find on a sinister mountaintop—spoiler!—many bad things, including but not limited to a terrifying passage clearly excavated by intelligent lifeforms leading to a Chamber of Horrors. Unfortunately for the expedition, the intelligent lifeforms are three-thousand-year-old rapist Martian lizard-vampires. Hijinx ensue. Eventually, (not) everyone goes home.

The HP Lovecraft leading lady does not exist, but his protagonists are also routinely men of science (in fairness to HPL, for all his many faults, his characters are slightly more convincing in their academic credentials than Pike’s). Often they are recounting for us the story of a sinister and obsessive old pal who went mysteriously missing or insane in the course of attempting to reanimate the dead (“Herbert West, Reanimator”), see into infernal planes (“From Beyond”), or revitalize the worship of ancient demonic beings (“The Case of Charles Dexter Ward”); their tales, they explain, are to warn other researchers off similarly luckless forays into academia. In this vein, At the Mountains of Madness is narrated by William Dyer, a geologist who participated in an ill-fated research expedition to Antarctica and who is now describing the horrors his team experienced there in order to deter further exploration.

On a sinister mountaintop, they found—spoiler!—many bad things, including but not limited to a terrifying passage clearly excavated by intelligent lifeforms leading to a splendid variety of Chambers of Horrors. Unfortunately for the expedition, the intelligent lifeforms are millennia-old evil tentacle beings from outer space whose own scientific activities resulted in a second, even more evil and much stickier race of formless sentient matter blobs with a passion for homicide. Hijinx ensue. Eventually, (not) everyone goes home. (To be clear, I also love this book.)

Lovecraft has received considerable serious critical attention, and despite—or, more likely, because of—his generalized misanthropy and notoriously specific racism, misogyny, and antisemitism, he has remained an enduring figurehead of American horror. Christopher Pike, though his books have sold millions upon millions of copies over the span of the last thirty years, is not somebody whose name you find prominently featured in the critical literature, unless by critical literature you mean “incredulous blog posts by middle-aged women revisiting the beloved thrillers of their early adolescence.” According to a biography of the author on a fan website, the Los Angeles Review of Books once compared Pike to none other than old Howard P., “a well-known New England writer of the early twentieth century,” describing Pike as “a master of creeping dread relentless [sic] disturbing the reader.”

Though At the Mountains of Madness and The Season of Passage share a lot of ground, this is not on the whole remotely accurate. Creeping dread is not a central element of Christopher Pike’s plot lines, which, whether focused on the nefarious activities of human or supernatural villains, are unanimously sensational, unsubtle, smutty, and gory.

In his heyday he was beloved by preteens in no small part because his characters were absolutely fucking in between their sojourns with monstrous entities of various kinds, but his wild melodramas also meet the elevated stakes of young adult life head-on. An adult reader might find faking one’s own death to be a somewhat extravagant response to run-of-the-mill humiliation, but when I encountered Pike’s novels as a teenager, framing one’s various enemies for murder read like a perfectly reasonable response to the slings and arrows of high-school fortune. Who among us can forget poor Jane of Gimme A Kiss, who decides to elaborately stage her own accidental death to punish her boyfriend and a trampy (natch) cheerleader who she believes are responsible for distributing her personal diary to the whole school, but is subsequently betrayed and set on fire (yes, really) by her backstabby bestie Alice, herself upset because she’s contracted oral herpes from the aforementioned boyfriend, who used to be her boyfriend? (I should note here that Gimme A Kiss is pretty tame, as far as Pike novels go.) Pike’s plots might be improbable in their execution, but they are deadly serious in their willingness to honor the extremes of misery and euphoria that characterize many adolescents’ experiences.

I think it’s safe to assume that Lovecraft didn’t have much fun in high school either, but his stories and novellas, as juvenile as they are, are almost plotless in comparison: A man goes somewhere he should not have gone and uncovers something that should not have been uncovered, yielding an abyss of monsters too frightening to be explicated fully. That’s pretty much it, across the board. Sometimes the monsters are ancient tentacle-beings and sometimes they are Black people. Creeping dread is really all Lovecraft has going for him. His characters are flat, and his stories often read like a laundry list of coy allusions to reeking horrors the narrator is simply unable to properly describe.

At the Mountains of Madness itself is so full of references to “certain horrors,” “certain manuscripts,” “certain stories,” and “certain elder gods” that one is on occasion tempted to hunt down Lovecraft’s petulant ghost and shake him. “The touch of evil mystery in these barrier mountains, and in the beckoning sea of opalescent sky glimpsed betwixt their summits, was a highly subtle and attenuated matter not to be explained in literal words,” asserts Dyer as he flies toward a doom he is equally incapable of describing, though he later suggests this inaptitude is out of service to his fictional academic audience and not a failure of his creator’s descriptive imagination: “In hinting at what the whole revealed, I can only hope that my account will not arouse a curiosity greater than sane caution on the part of those who believe me at all. It would be tragic if any were to be allured to that realm of death and horror by the very warning meant to discourage them.” (Fear not, gentle reader: Pike is nowhere near so shy when it comes to, say, graphic renditions of rapist Martian lizard-vampire sex.)

A charitable critic would argue that Lovecraft is a conjuror of atmosphere, a master of genuinely chilling moments; a mildly astute one would point out that what Lovecraft feared tells us a lot more about Lovecraft and his tenacious fandom than it does anything about terror. “The oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is fear of the unknown,” writes Lovecraft in Supernatural Horror in Literature, his long and influential essay on what he terms “weird” fiction.

Well, maybe. In Lovecraft’s case, his terrors are so transparent as to be almost comical, if they were not rooted in the foundational mythologies of American culture. For Lovecraft, the unholy and terrifying unknown notoriously comprises Black people, women, Jews, and elderly tentacled beings from another planet, not necessarily in that order. It requires little effort to work backward from contemporary neofascist mythologies—the predatory homosexual, the depraved criminal of color, the wanton woman—to Lovecraft’s febrile soup of racist, xenophobic paranoia.

But while I would not identify Christopher Pike’s work as cutting-edge intersectional feminism, and it’s worth pointing out that it deploys problematic tropes on the (few) occasions it features characters of color (in The Season of Passage, a young Native man has special connections to the natural world and, it’s implied, psychic powers; or in, say, Spellbound, where Kenyan trainee shaman Bala poses as an exchange student at a Wyoming high school whilst in pursuit of a homicidal “African” vulture spirit possessing one of his new classmates, I shit you not), he is much less likely than Lovecraft to fix the Other as the sum of all fear.

And Pike’s work, unseriously as it is regarded, is arguably as enduring. (To say that I am awaiting the forthcoming Mike Flanagan feature film of The Season of Passage with glee would be an understatement.) Though there are a few genuinely beautiful passages in At the Mountains of Madness, Lovecraft is on the whole no better a stylist, and he’s certainly no better a storyteller. “Lovecraft was an exceptionally, almost impeccably, bad writer,” noted Ursula K. Le Guin in a 1976 review of a Lovecraft biography; but even she goes on to observe that “though dissatisfied, one may be fascinated, as by any extreme psychological oddity.” (As far as I know, Le Guin never had anything at all to say about Christopher Pike.)

I would never force anyone to read either of these novels, but I would argue there’s something more to them both than mere psychological oddity. Loving these books unironically—which I do—requires a willful suspension of disbelief and the kind of dissociative work that will be familiar to non-white, non-straight, non-cis, and non-male readers who grew up projecting themselves into stories where their own bodies rarely constituted persons, let alone protagonists. In Lovecraft’s universe, Howard himself would point out that I have a lot more common ground with Cthulhu than I do William Dyer; for that matter, I have a lot more in common with a three-thousand-year-old rapist Martian lizard-vampire than I do Lauren Wagner. But both writers are so committed to the prodigious outputs of their singular cosmologies—for Pike, a wild mishmash of Hindu theology, teen scream queens, and lizard people; for HP, a nihilistic void of tentacle monsters puppeteering the actions of their unwitting human dupes–that, for a certain kind of reader (me), the wildness of the ride brings its own peculiar and irreplaceable joys.

Buy the Book

The Darling Killers

Whether Pike himself ever read Lovecraft is unclear. One of Season’s astronauts brings along his personal science-fiction library, allowing Pike to provide a loving bibliography of his own influences (as well as a truly incredible scene in which Lauren’s colleague Gary flips through Dracula for lizard-vampire research purposes: “‘Dracula was a count who lived in Transylvania. Bram Stoker was a writer who lived in Ireland. We’re on Mars, Gary!’” Lauren responds); there’s no mention of Lovecraft, and the notoriously reclusive Pike has never referred to Lovecraft in any of the interviews with him I’ve found. It’s likely that the parallels between their work are as organic as the parallels between their experiences: white American men writing in similar decades, for whom monsters are unsubtle, female characters are the ultimate aliens, and the unknown is a location of terror rather than possibility.

Both The Season of Passage and At the Mountains of Madness rely on the classic horror frame of We Were Dumb Enough to Look Into the Abyss, Please Don’t Make the Same Mistake: “Certain lingering influences in that unknown antarctic world of disordered time and alien natural law make it imperative that further exploration be discouraged,” Dyer tells us; Season’s hapless vampire-battling cosmonaut captain Dmitri sadly writes at the end of his own journal, discovered by Lauren long after his grisly demise, that “Now there can be no warning for those who should follow us here. I feel sorry for those people.”

Despite these pleas, there is no question of whether we will follow these poor fools into the landscape of the monstrous; one of the many pleasures of horror is that it allows us to experience the terrors of the darkened basement without having to descend the creaking staircase ourselves. “Of course,” Lauren observes toward the final third of The Season of Passage, “you had to invite them in—all the stories said that. You had to make a decision.” Lauren’s talking, obviously, about lizard-vampire people, not horror novels. Nevertheless, the invitation is up to you.

If you’re willing to open the door, you never know who’ll you’ll get to have for dinner.

Sarah McCarry’s most recent novel is The Darling Killers. She writes occasional letters about sailing, ice, and books; you can sign up for them here.