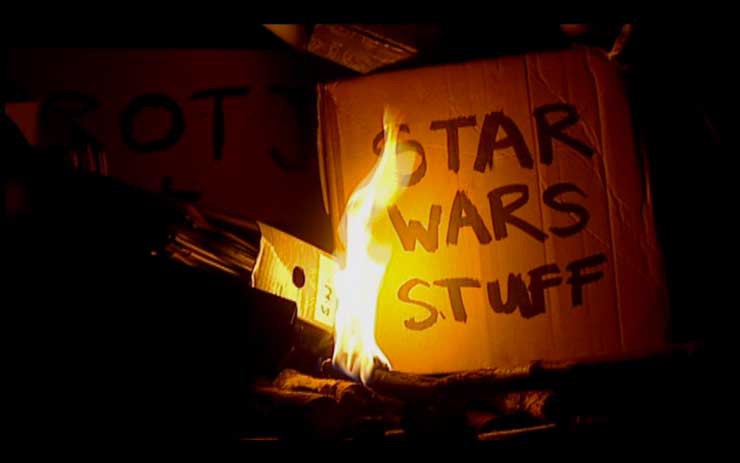

In the second season of Simon Pegg’s excellent sitcom Spaced, we see his character Tim burning all of his Star Wars memorabilia just like Luke burns Vader’s body in Return of the Jedi. Pegg’s character Tim does this in response to his hatred of The Phantom Menace, but is Simon Pegg now doing the same thing with Spaced? Quoted recently in an interview for Radio Times, Pegg insinuated that our cultural obsession with sci-fi might be a bit “childish.”

From Radio Times:

Now, I don’t know if that is a good thing. Obviously I’m very much a self-confessed fan of science-fiction and genre cinema. But part of me looks at society as it is now and just thinks we’ve been infantilised by our own taste.

Now we’re essentially all consuming very childish things—comic books, superheroes… Adults are watching this stuff, and taking it seriously!

I’ll never stop loving Simon Pegg no matter what, but here are a few reasons why science fiction doesn’t have to be seen as childish.

Science Fiction Requires Both Imagination and Intelligence

Pegg references Avengers 2 specifically later on in the article, and I can buy an argument that this specific movie is a little childish. Even so, there’s still an amount of imagination and intelligence that an audience member needs in order to make it through the movie and “understand” the basics of what have occurred. I’m not crazy about the way artificial intelligence was discussed in the Avengers: Age of Ultron, but I’ll actually take it over The Godfather any day of the week. This isn’t to say that Avengers: Age of Ultron is a better piece of art than The Godfather, just that I think it stimulates the imagination more. What would you do if your worst impulses manifested into an army of robots that want to kill all your friends? Robert Downey, Jr. has just as much angst as Al Pacino, if not a little bit more. The difference is that Tony Stark is a scientist and an engineer and is allowing his imagination to lead him down avenues that can change the world for the better, even if that goes wrong, and Michael Corleone is, in the end, only a killer.

Superheroes are the New Mythology Because They Are the Old Mythology

Speaking directly to the critique of Avengers and superhero movies, I feel like the knee-jerk criticism of these films is informed by too narrow a view of narrative history. Gods and god-like beings have always been an obsession in narrative art. A literal Nordic legend—Thor—exists inside of the Marvel comics universe and has for decades. The reason why there seems to be more focus on superheroes now than ever before is only because the technology to make good-looking comic book movies has finally arrived. Superhero movies were less commercially viable before the 21st century because of the limitations of visual effects, but superheroes were still around in comic books and in cartoons. If we view cinema as the end-all-be-all of what “counts” in the culture, then yes, superhero narratives are currently enjoying a boom. But they’ve been there the whole time, just as influential and just as ready for us to pour all of our allegorical and personal feelings into them.

Also, no one gets mad about Hamlet remakes, so why get mad about superhero remakes?

Science Fiction Can Inspire Real Change

While I think Pegg is on to something when he worries that there’s a tendency in geek culture to obsess over small moments or focus so intently on minutiae that the larger context vanishes, that doesn’t mean those actions prevent sci-fi and its related genres from impacting the world in a real way. The easiest example to cite is Star Trek, for which Pegg currently acts and writes. Dr. Martin Luther King was a fan of the original series and saw it as an affirmation of what humanity could be, others were inspired to become real astronauts, and for writers like me, a certain reverence for and love of literature was has always been a part of Star Trek, and I believe it’s helped to inspired generations and generations of readers. Not all science fiction is socially progressive, but the best kind is, and that fiction in turn can inspire great social works.

Allegory is More Powerful than Realism

Though Simon Pegg is certainly speaking about more mainstream pop science fiction, it’s important to remember that the nature of allegory, of unreality, can be way more powerful than literary realism. Unsurprisingly, one of science fiction’s greatest writers has something to say about this. From Ursula K. Le Guin, writing in her essay collection Dancing at the Edge of the World:

We cannot ask reason to take us across the gulfs of the absurd. Only imagination can get us out of the bind of the eternal present, inventing hypothesizing, or pretending or discovering a way that reason can then follow into the infinity of options, a clue through the labyrinths of choice, a golden string, the story, leading us to freedom that is properly human, the freedom open to those whose minds can accept unreality.

For me, this means that while we “need” reality to survive, we might not have the most profound revelations if we stay there exclusively. Of course, Pegg might be arguing that there is too much of an obsession with unreality, but I’d like to believe that’s not true of the present moment…

Immersion in an Artistic and/or Pop Culture Pursuit is Not Inherently Socially Irresponsible

There’s an idea (a bias?) that pop culture or any artistic endeavor that relies more an aesthetics than “important content” is somehow frivolous. The world of fashion is a good example here: because it’s just the industry of “pretty people,” then fashion is nonsense and destroys society, right? Well, not really. Famed fashion photographer (and humble, humble man) Bill Cunningham once defended fashion thusly:

Fashion is the armor to survive the reality of everyday life. I don’t think you could do away with it. It would be like doing away with civilization.

If you substitute “science fiction” or “geek culture” for “fashion,” here I think it’s pretty much the same thing—even when these facets of popular cultural are at their lightest and fluffiest, they still serve an important function, all the same.

To sum up, I think I know what Simon Pegg means by his sentiment: that his viewpoint is coming from somewhere personal and is informed by the present day, and possibly not meant to encompass everyone who enjoys science fiction. And I imagine if I was him, working on the high profile projects that he does, I might be a little burnt out on all things geek, too. But it doesn’t mean that the genre (and genres) of imagination are destroying us, or making us into terrible children.

When J.J. Abrams has an open temper tantrum and cries, or the cast of Orphan Black all starts sucking their thumbs in public, I’ll worry. Until then, the kids, whether they be sci-fi geeks or not, are certainly, and geekily, all right.

This article was originally published May 19, 2015.

Ryan Britt is the author of Luke Skywalker Can’t Read and Other Geeky Truths. His writing has appeared with The New York Times, The Awl, Electric Literature, VICE and elsewhere. He is a longtime contributor to Tor.com and lives in New York City.