I recently spent time in the New Mexico desert, which felt very fragile indeed. From threats of wildfires outside Albuquerque to annually decreasing water levels in Elephant Butte Lake to the incredible emptiness of the hills rippling away from Route 25, it seemed a landscape poised on the brink of disaster. It was not just the fragility of the land; maybe it was the stars wheeling overhead or the moon’s startling luminescence when it finally peeked over Turtleback Mountain, but the very air felt thin, as though one merely had to press against it to part the curtain between worlds.

Despite all this, the desert is very much alive, its inhabitants remarkably tenacious. Yucca and aloe plants poke through the soil, lizards scurry over rocks in search of insects, and coyote and cattle companionably share the dusty roads. Humans, too, have made a home here and will likely continue to do so for many years to come. It is this balance between fragility and tenacity that makes not just the desert so fascinating to me, but our entire planet in the 21st century, poised as it also seems on the edge of the abyss.

Here are five books that feature fragile worlds. Though they come from different genres, each one explores this tension between apparent weakness and actual strength, between our known world and others that may exist, if only we can discover how to part the curtain between them.

Girl in Landscape by Jonathan Lethem

Part sci-fi, part Western, and part post-apocalyptic dystopian dream, Girl in Landscape begins with disaster. Not only has Earth’s climate crumbled, but Pella Marsh’s mother has died from a brain tumor. Grieving and abruptly ousted from political office, Pella’s father Clement whisks her and her siblings off to the Planet of the Archbuilders to attempt a fresh start. Here, they find a hot dry land populated by the structures of a failed civilization, semi-transparent “household deer” that skitter around the corners of their home, and the remaining Archbuilders themselves: furry, scaled creatures with twenty thousand languages at their command. It is 13-year-old Pella’s fierce will to survive and intense curiosity about her new environment that captured me most. Everything seems to be collapsing around her, but she resists all attempts to keep her fragile, whether it is the stupefying acclimatization pills being pushed on her or the dismissive attitude adults so often adopt towards the young.

How High We Go in the Dark by Sequoia Nagamatsu

This collection of linked short stories is another long hard stare into our possible future. In the year 2030, an archaeologist travels to the Arctic Circle, where he unwittingly unleashes a deadly virus while examining the remains of a girl his scientist daughter discovered in the melting permafrost. The succeeding stories illustrate the Arctic Plague’s path of destruction across the globe and the imaginative, often heartbreaking ways in which humans strive to combat the despair it brings. From euthanasia theme parks for children to a talking cloned pig who realizes his organs will be harvested to death hotels and a spaceship to another, hopefully better, planet, How High We Go in the Dark takes tremendous leaps without asking permission and yet always seems to land beautifully on its feet.

Feed by M.T. Anderson

This is hands-down my favorite YA dystopian novel. Originally published in 2002, its concept of the “feed” brilliantly predicted our current relationship with the internet, social media, and consumerism. In this book, every person (at least those who can afford it) has a chip implanted in their brain. This chip functions largely as our internet does, allowing its owners access to everything from designer clothes to trendy music to all the information known to humans. They must merely think and their desired product will arrive, its cost automatically deducted from their “credit.” When popular teenager Titus travels with his vapid friends to the Moon on an afternoon jaunt, however, a hacker jams their feeds, sending their brains into a tailspin. Titus and his buddies manage to recover, but the real tragedy lies in the fate of non-conformist Violet, a less wealthy teen whose inferior-quality feed was also hacked. Trapped in a dying world where the rich hunt whales in polluted seas and lesions are beginning to take over human bodies, Violet devises a daring plan to resist the feed, but how can you fight something that is hard-wired into your brain?

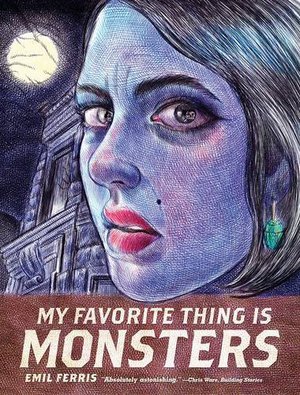

My Favorite Thing Is Monsters by Emil Ferris

This is a big, fat, wonderful graphic novel that has everything I love in a book: tangled family relationships, horror movies, political turmoil, traumatic personal history, grief, tender coming-of-age, questions of race and identity, queer love, and yes, monsters. Karen Reyes is a ten-year-old social outcast who loves Creature Features and pictures herself as the Wolfman. She is also a detective investigating the mysterious murder of her beautiful neighbor Anka Silverberg, a Holocaust survivor who has recorded her awful past on cassette tapes. Clad in her artist brother’s raincoat and fedora, Karen wanders the seedy streets and art museums of 1960s Chicago in search of clues, ultimately discovering more about herself—and her family—than she bargained for. Everything around her seems fragile. Some, like Anka, have already vanished, while others, including Karen’s terminally ill mother and morally conflicted brother, are rapidly falling apart. Even her society is in flux, on the cusp of great changes that will shake it to its core. Karen, too, appears fragile; she must pretend she is a monster simply to navigate each treacherous day. We have a sense, however, that Karen will not disintegrate so easily. Like Pella Marsh from Girl in Landscape, she learns to stand up to what seeks to destroy her. Hopefully the much-anticipated sequel will show us how tenacious Karen can actually be.

Nightbitch by Rachel Yoder

The world in this debut novel is not fragile at all. It is solid, substantial, grindingly and exhaustingly real, cluttered with playgrounds and plastic toys, library reading circles and perfectly groomed moms with perfectly groomed kids. It is the protagonist’s grasp of this world that is tenuous. To her, reality seems a mirage, set in place to distract her from her true self, a formerly autonomous woman now swamped by motherhood and its demands. Initially called only “the mother,” the main character is an artist who has paused her career to care for her son while her husband travels for work. She knows she should value this privilege – it’s a dream life, is it not? – but she is worn out, physically, emotionally, and spiritually depleted. Then, one day, while listening to her son cry, she discovers something new: rage. As Yoder tells us, “That single, white-hot light at the center of the darkness of herself – that was the point of origin from which she birthed something new, from which all women do.” Soon she discovers other things: an odd patch of hair at her neck’s nape, sharper canines, a ravenous appetite for raw steak. A delightfully feral look at what it means to be a mother, a wife, and a woman in contemporary American society, Nightbitch gives us a character unafraid to crawl into the night on all fours, ready to snap the thin line between one world and the next with her teeth. I would love to see Nightbitch and Karen Reyes from My Favorite Thing Is Monsters meet. I imagine they would have a great deal to say, or perhaps howl, to each other.

Buy the Book

Walk the Vanished Earth

Erin Swan is a writer of fiction and nonfiction whose work has been published in such literary journals as Portland Review, The South Carolina Review, and Inkwell Journal. A graduate of the MFA program at the New School, she lives in Brooklyn and teaches English at a public high school in lower Manhattan. Walk the Vanished Earth is her first novel.

Garth, the planet in David Brin’s “Uplift War” came to mind the instant I saw the title…an ecological disaster world devastated by (the devolution of) its former occupants.

I am immediately inspired to think of Mary Gentle’s The Golden Witchbreed and its sequel, Ancient Light. Then, of course, Leigh Brackett’s trilogy of Eric John Stark, The Book of Skaith, is a series of books about a world that is more than just fragile, it is plain dying, and its inhabitants have tried a range of attempted solutions.

James P. Hogan’s Echoes of an Alien Sky is another example, in which the fragile world was our own.

Carol Kendall’s Minnipins series (The Gammage Cup and The Whisper of Glocken) follows two widely separated groups of the eponymous intelligent species, which both live in worlds that are much more fragile than most Minnipins suspect.

EARTH by David Brin is definitely about a world on the edge–hello, black hole devouring it!