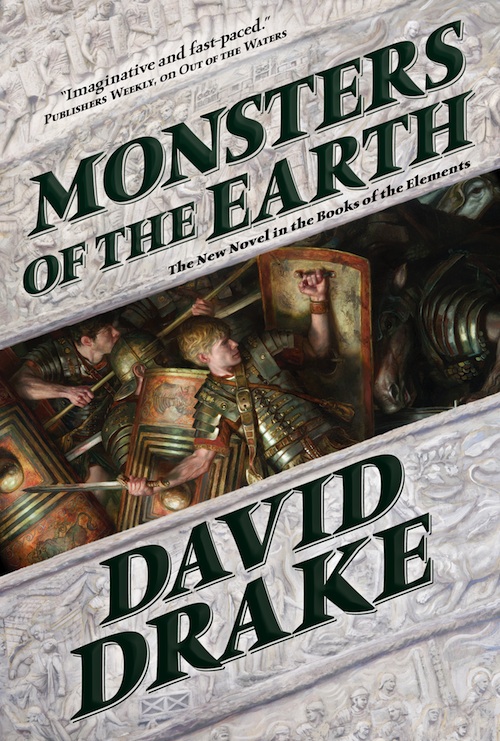

Check out Monsters of the Earth, the new novel in David Drake’s ongoing chronicles of Carce, The Books of the Elements, available September 3rd!

Governor Saxa, of the great city of Carce, a fantasy analog of ancient Rome, is rusticating at his villa. When Saxa’s son Varus accompanies Corylus on a visit to the household of his father, Crispus, a retired military commander, Saxa graciously joins the party with his young wife Hedia, daughter Alphena, and a large entourage of his servants, making it a major social triumph for Crispus. But on the way to the event, something goes amiss. Varus, who has been the conduit for supernatural visions before, experiences another: giant crystalline worms devouring the entire world.

Soon the major characters are each involved in supernatural events caused by a struggle between two powerful magicians, both mentored by the deceased poet and mage Vergil, one of whom wants to destroy the world and the other who wishes to stop him. But which is which? There is a complex web of human and supernatural deceit to be unraveled.

CHAPTER I

Gaius Alphenus Varus looked back over his shoulder. There were only a dozen servants ahead of him and his friend Corylus as they wound through the streets of Puteoli to the wharfs on the Bay itself. Behind, however, there must be a hundred people. More!

“We look like a religious procession,” Varus muttered. He tugged the shoulder of his toga, a square of heavy wool with the broad purple stripe of a senatorial family, to settle it a little more comfortably.

Varus had no taste for pomp, but he was polite, so he couldn’t treat this occasion as though he were merely a scholar who needed only a tunic and at most one servant to carry his satchel of writing and reference materials. That would be insulting to the friend of Corylus’ father whom they were visiting—and to Varus’ own father, Gaius Alphenus Saxa: senator and recent consul of the Republic of Carce.

Corylus chuckled. He said, “We look like a train of high officials going to consult the Sibyl, you mean? That’s a good five miles from here, though, farther than I want to hike, wearing a toga on a day this warm.”

He and Varus were the same age, seventeen, but Publius Cispius Corylus was taller by a hand’s breadth and had a bright expression that made him look five years younger than his companion. Corylus had gotten his hair, reddish with touches of gold, from his mother.

He had been born on the Rhine frontier where his father had commanded a cohort. His mother, Coryla, was a local girl who had died giving birth. Soldiers couldn’t marry while on active duty, but Cispius had acknowledged his son as legitimate.

“Saxa wouldn’t be in the best shape after a five-mile hike,” Varus said mildly, pitching his voice so that only his friend was likely to hear the words. “Let alone Hedia.”

Hedia was Saxa’s third wife and therefore by law the mother of Varus and his sixteen-year-old sister, Alphena. Hedia was twenty-three, beautiful, and sophisticated to the point of being, well, fast.

In most senses, one could scarcely imagine a less motherly woman than Hedia. In others—in all the ways that really mattered—well, she had faced demons for her stepchildren. What was even more remarkable was that the demons had been the losers.

Varus was a bookish youth who had almost no interests in common with his stepmother. He had nevertheless become glad of the relationship, and he was very glad that his father had a champion as ruthlessly determined as lovely Hedia.

“It’s not something I need, either,” Corylus said. “Especially not in a toga. I told Pulto—”

He nodded to his servant, who had been the elder Cispius’ servant throughout his army career.

“—that he needn’t bother wearing one unless he wanted to impress somebody.”

Though Corylus kept a straight face, Varus knew the servant well enough to chuckle. He said, “How did Pulto respond to that?”

“He said that if he needed to impress somebody, he’d do it with a bloody sword,” Corylus said, grinning again. “Like he’d done a couple hundred times before, he figured. I told him I hoped that wouldn’t be necessary on a visit to an old friend like Marcus Veturius.”

Pulto was a freeborn citizen of Carce, unlike the other servants and attendants accompanying the nobles and dignitaries present. That said, Pulto had spent his army career keeping Publius Cispius as comfortable and well fed as was possible in camp, and alive when they were in action.

Since Corylus’ father believed in leading from the front, “a couple hundred” Germans and Sarmatians probably had met the point of Pulto’s sword. Pulto had accumulated medals over the years, but his real honors were the scars puckering and crisscrossing his body.

An animal screamed in the near distance, meaning they were nearing the compound where Veturius stored the beasts he imported. From here he shipped them to amphitheaters—largely in Carce, but all over Italy.

Varus felt his lips tighten. His first thought had been that the cry had come from a human in pain, but it was too loud.

“An elephant, perhaps?” said Corylus, who must have been thinking the same thing.

“Loud even for that,” Varus said. “Well, we’ll know soon enough.”

The spectators lining both sides of the street shouted, “Hail, Lord Saxa!” and similar things. Balbinus, the steward who ran Saxa’s home here on the Bay of Puteoli, must have planned extremely well.

This district housed sellers of used clothing and cookware whose booths would normally fill the street. A detachment of husky servants had cleared them back before Saxa and his entourage had tried to pass through, but the squad leading the procession itself was flinging little baskets to the crowd.

The gifts—sweet rolls, candied fruit, or a few copper coins—changed the residents’ mood from riotous to a party and led them to cheer instead of finding things of their own to hurl. Buildings in Puteoli didn’t reach four or five stories as they did in Carce, but even so bricks thrown from a rooftop would be dangerous.

“Varus… ,” Corylus said, his voice suddenly husky. “I, ah… That is, my father feels greatly honored that former consul Saxa has accepted his invitation to visit the compound. I don’t think Father cares greatly for himself, but it raises him in the eyes of his old friend Veturius. I, ah… I thank you on behalf of my father, and on my own behalf, because you’ve so pleased a man whom I love.”

“I accept your thanks,” Varus said mildly. “I believe that’s your father waiting in the gateway, isn’t it? And I suppose that’s Veturius in the toga beside him.”

Corylus already knew that Varus hadn’t encouraged Saxa to come with him to the animal compound, so there was no need to repeat the statement. Indeed, the whole expedition had grown of itself, the way a rolling pebble might trigger a landslide.

The importer Marcus Veturius had told his friend Publius Cispius that he had brought back a group of unfamiliar animals from deep into Africa. Cispius had suggested he send for his son, Corylus, a student in Carce, who was learned and might be able to identify the creatures.

Corylus had asked to bring along his friend and fellow student Gaius Varus, whom he said was even more learned. After a grimace of modesty, Varus could have agreed. Corylus was himself a real scholar as well as being a great deal more; but dispassionately, Varus knew that his own knowledge was exceptional.

All that would have been a matter of academic interest, literally: a pair of students visiting an importer’s compound to view exotic animals. Everything changed because Saxa, Hedia, and Alphena were spending the month nearby at the family house on the Bay.

Saxa was not only a former consul—which was merely a post of honor since all real power was in the hands of the Emperor and of the bureaucrats who had the Emperor’s ear—but also one of the richest men in the Senate. Anything Saxa did was done—had to be done—on a grand scale.

Saxa had no political ambition, which was the only reason he had survived under a notably suspicious emperor, but he did desperately want to be seen as wise. Unfortunately, although he loved knowledge and knew many things, Saxa’s mind was as disorderly as a jackdaw’s nest.

Varus, however, was a scholar. Despite his youth, he had gained the respect of some of the most learned men in Carce—including Pandareus of Athens, who taught him and Corylus. Instead of being envious, Saxa basked in his son’s successes.

Saxa hadn’t been a harsh father, but he had scarcely seemed to notice his children until recently. Now he was making an effort to be part of his son’s life and so had asked to accompany Varus to view the strange animals.

Varus hadn’t even considered asking his father to stay out of the way, but his presence had turned a scholarly visit into a major social undertaking. A younger senator named Quintus Macsturnas had bought the whole shipment of animals to be killed at a public spectacle in Carce to celebrate his election as aedile. When Macsturnas heard that Saxa planned to visit the compound, he had asked to accompany his senior and even wealthier colleague.

Varus smiled, though his lips scarcely moved. Courtesy aside, how could he—or his father—have denied Macsturnas permission to view the animals he himself had purchased?

Besides which, the even greater pomp was certain to please Cispius and his old friend. The aedile’s attendants were added to those of Saxa and the separate establishments of Hedia, Alphena, and—because this was now a formal occasion—the ten servants accompanying Varus himself.

“I wonder… ,” said Corylus, looking at the following procession and returning Varus’ attention there also. “If there’ll be sufficient room in the compound, what with Veturius just getting in a big shipment?”

He shrugged, then added, “I don’t suppose it matters if the servants wait in the street, though.”

Varus consciously smoothed away his slight frown, but he continued to look back. Corylus will stop me if I’m about to run into something.

A dozen servants walked directly behind the two youths. They were sturdy fellows who carried batons that would instantly become cudgels if there was a problem with local residents. Next were the two senators and their immediate family—in Saxa’s case—and aides.

Varus faced front again. “The old man behind Macsturnas?” he said. “The barefoot old fellow. Do you recognize him, Publius?”

Corylus looked back and shrugged. “Can’t say that I do,” he said. “Is there something wrong with him?” He coughed and glanced sidelong at Varus. “That is, he seems pretty harmless to me.”

“There’s nothing wrong that I can see,” Varus said, feeling embarrassed. Because he was speaking to Corylus, however, a friend with whom Varus had gone through things that neither of them could explain, he added, “I caught his eyes for a moment when I looked back. He either hates me, or he’s a very angry man generally. And I don’t recall ever having seen him before in my life.”

“He may be the aedile’s pet philosopher,” Corylus said equably. “Though Macsturnas strikes me as too plump to worry much about ascetic philosophy. And the fellow doesn’t have a beard.”

“If he were the usual charlatan who blathers a Stoic mishmash to a wealthy meal ticket,” Varus said, “he would have a beard as part of the costume. Which implies that whatever he is, he’s real. And I agree that Macsturnas doesn’t appear to be philosophically inclined, though we may be doing him an injustice.”

Varus found comfort in his friend’s comfortable acceptance of present reality. Corylus didn’t worry about every danger that could occur, but he was clearly willing to deal with anything that did happen.

Corylus’ father, Publius Cispius, had started as a common legionary and been promoted to the rank of knight when he retired after twentyfive years in service. Corylus also intended an army career, but his would begin as an officer: a tribune, an aide to the legate who commanded a legion as the Emperor’s representative.

That was the formal situation. Informally, Corylus had been born and raised on the frontiers and he’d spent more time on the eastern bank of the Danube—with the scout section of his father’s Batavian squadron—than most line soldiers did. Corylus didn’t talk about that to Varus or to other students, but sometimes Varus listened while Pulto talked to Saxa’s trainer, Lenatus, another old soldier.

There was a great deal Varus didn’t understand about his friend’s background, but he understood this: Corylus might be frightened, but fear would never stop him from doing his duty to the best of his ability.

He was, after all, a citizen of Carce. As am I.

“Eh?” said Corylus.

I must have spoken aloud. “I was thinking that we have duties as citizens of Carce,” Varus said. “As well as our rights.”

Corylus said, “That had occurred to me, yes.”

Part of Varus’ mind considered that a mild response for a soldier to make to a civilian who was talking about duty. His consciousness was slipping into another state, however, in which the Waking World flattened to shadow pictures like those on the walls of Plato’s Cave of Ideal Forms.

Corylus had joked about them being a royal procession visiting the seeress whose temple was nearby at Cumae. Varus in his mind was climbing a rocky path to an old woman who stood on an outcrop above all things and all times.

She was the Sibyl, and during the past year she had spoken to him in these waking dreams.

Hedia saw Varus glance in her direction from beyond the squad of attendants. She smiled back, but almost in the instant she saw him stiffen as his eyes glazed.

Varus faced front again. He was walking on, his legs moving with the regularity of drops falling from a water clock. Hedia had seen the boy in this state before. Seeing him now drove a blade of ice through her heart.

Smiling with gracious interest, Hedia looked past Saxa and said to the aedile, “If I may ask, Lord Macsturnas—why did you decide to give a beast show in thanks for your election instead of a chariot race?”

In a matter touching her family, Hedia would do whatever was proper. Not that poor, dear Saxa was capable of thinking in such terms, but it was possible that one day he would need a favor from Macsturnas. If on that day the aedile remembered how charming Saxa’s lovely wife had been—well, courtesy cost Hedia nothing.

Aedile was the lowest elective office, open to men of twenty-five; Macsturnas was no older than that and seemed younger. An aedile’s main duties—even before the Emperor began to guide the deliberations of the Senate and therefore the lives of every man, woman, and child in the Republic—were to give entertainments to the populace.

“I thought it was more in keeping with my family’s literary interests to offer the populace a mime when I was chosen consul,” Saxa volunteered. “My son is quite a poet, did you know?”

Hedia had no more feeling for poetry than she did about the defense of the eastern frontier: both subjects bored her to tears. Varus had assured her, however, that his one public reading had proved to him that he had no poetic talent and that he should never attempt verse again.

Saxa, in trying to become part of the life of the son whom he had ignored for so long, was resurrecting an embarrassment. Well, that was easy to cover.

“Though of course we’re great fans of chariot racing also,” Hedia lied with bubbly innocence. “After all, some of the most illustrious men in the Republic are. We follow the White Stables in particular.”

Hundreds of thousands of spectators filled the Great Circus for even an average card of chariot racing; it was by far the most popular sport in the Republic. Hedia didn’t care about that, though charioteers tended to be more lithely muscular than most gladiators and thus of some interest.

The Emperor was a racing enthusiast. Hedia cared about that. And because the Emperor backed the Whites, Hedia would swear on any altar in Carce that her husband did also. She didn’t have any particular belief in gods, but she felt that any deity worth worshiping would understand that the survival of the Alphenus family was more important than any number of false oaths.

“Well, you see… ,” said Macsturnas, his tone becoming more oily and inflated with every syllable. “My family were nobles of Velitrum. Our house was ancient before the very founding of Carce.”

He gestured with both hands, as though flicking rose water off his fingers as he washed between courses of a meal. A more prideful man than Saxa might have taken offense at the implied slight; and though Saxa’s wife, also a noble of Carce, didn’t let her smile slip, this bumptious fellow might one day regret his arrogance.

“To Etruscans of our rank,” Macsturnas continued, “gladiatorial games are not a sport but a religious rite. I therefore expected to hire pairs of gladiators for my gift to the people. But then the agent I sent to Puteoli learned that Master Veturius was back from Africa with a number of unique animals. I ordered him to purchase the whole shipment and came down to look at them myself. My gift will be unprecedented!”

Varus’ sister, Alphena, was out of sight. She and Hedia had been getting along well since recent events had forced them to see each other’s merits, but the relationship of a sixteen-year-old with her stepmother was bound to have tense moments.

Today Alphena had planned to walk with her brother and Corylus at the head of the procession; Hedia had forbidden her to do so. Instead of joining Hedia and the two senators, Alphena had flounced back to the very end.

Hedia hadn’t objected; the girl wouldn’t get into any trouble surrounded by her personal suite of servants and the roughs of the senators’ households who formed the rear guard. Alphena probably wouldn’t have gotten into trouble in the company of Varus and Corylus, either, but Hedia knew too much about taking risks to allow her daughter to take a completely unnecessary one.

Varus, of course, wasn’t a problem; nor was even Corylus, not really. Varus’ friend was a very sensible young man. The attitude of a sixteenyear-old girl toward a youth as brave and handsome as Corylus might become a problem, though, if they spent too much time together.

For all his virtues, Corylus was a knight and therefore an unsuitable husband for a senator’s daughter. After Alphena was safely married, of course, her behavior was a concern for her husband, not her mother.

Hedia smiled faintly. She had been sixteen herself not so very long ago. Alphena didn’t have the personality required to make a success of her stepmother’s lifestyle.

Macsturnas laid his hand on Saxa’s shoulder and leaned across the former consul to bring himself nearer to Hedia. In a conspiratorial tone—though a rather loud one in order to be heard over the cheerful banter of spectators—he said, “The man accompanying me, Master Paris—he’s a priest of great learning. He honors you by asking to join us, Lord Saxa. Paris is the recipient of the wisdom passed down from the great founders of the Etruscan race.”

If Etruscan wisdom is so remarkable, Hedia thought, smiling softly toward the pudgy little man, then why is Velitrum a dusty village in the hills and Carce the ruler of all the known world?

“Is this soothsayer helping you plan your gift, Quintus Macsturnas?” Saxa asked, glancing for the first time at the Etruscan who walked behind them. “Choosing the day for you to give it, that is?”

Paris glared at Saxa, and at Hedia, who turned with her husband. She hadn’t paid any attention to the scraggly old man until now. He was barefoot, wearing a simple tunic and a countryman’s broad-brimmed hat. His appearance made him unusual in a nobleman’s entourage— but not interesting, at least not to Hedia.

And what an odd name. Surely he can’t be a freedman whose former owner gave his slaves names out of Homer?

“Oh, no, nothing like that,” Macsturnas said, lowering his voice to where Hedia was as much reading his lips as hearing the words. “He, ah… I knew of Paris, of course, but I haven’t had actual dealings with him. As some of my fellow Etruscans have. He asked to come along today to see the scaly monkeys. I, ah… I really don’t know why.”

There was a look of nervousness on Macsturnas’ pudgy features, as though he actually cared about what the old man thought. Even if Paris was freeborn, the opinion of a poor commoner was no proper concern for a noble of Carce.

“Well,” said Saxa expansively. “I’m more than happy to have your little priest get the benefit of my son’s wisdom. Varus is an exceptional scholar, you know. Marcus Atilius Priscus assured me of that when we were last chatting. Do you know Priscus? He’s the most learned of our senatorial colleagues, in my opinion. He’s head of the Commission for Sacred Rites and a great friend of my son’s teacher, Pandareus of Athens.”

Hedia almost giggled. That sort of patronizing boast would be alien to her husband under most circumstances. Apparently Saxa hadn’t been quite as unmoved by Macsturnas’ tone as she had believed.

On the other hand, everything Saxa had said was quite true. Varus was quite a remarkable youth… as in different fashions was his friend Corylus. Corylus was a respectable scholar himself—that was how a noble like Varus had become friends with a youth of only knightly rank—but he was also an accomplished athlete and a very handsome young man.

Unfortunately—Hedia smiled ruefully at herself—Master Corylus also had better sense than to chance an affair with a senator’s lovely young wife. Well, that was probably for the best.

She was glad that Saxa was taking an interest in Varus. Though Saxa was anything but a social manipulator, his wealth allowed him to give dinners at which his son would be introduced to the sort of people whose help he would need while steering his future course through society. Hedia had recently begun to craft guest lists that suited that purpose, and her husband acquiesced to them happily.

She wished she could find some more worldly fellow to give Varus a grounding in the more earthy aspects of life, though. All the men Hedia knew were rather too worldly, unfortunately. The last thing she wanted was to turn her son into a hard-drinking wastrel like those with whom she had whiled away her time during her previous marriage, to Gaius Calpurnius Latus.

She still met them, though more discreetly since she married Saxa. Saxa was a very sweet man, but Hedia had needs that her husband couldn’t satisfy. Saxa had known he wasn’t marrying a Vestal. She suspected that he was secretly proud of her and her reputation, but it wasn’t a subject they discussed.

The procession was about to reach the entrance to Veturius’ animal compound. The walls were masonry—coarse volcanic tuff from the beds layering all the land overlooked by Mount Vesuvius—and over ten feet high.

Hedia had never visited a beast yard before, but she often toured gladiatorial schools when she was summering here on the Bay. The schools were fenced off—the gladiators were slaves, after all, and under a stiff training regimen—but she hadn’t seen any barriers so impressive as this.

“I wonder why Veturius has such walls?” Hedia said aloud. “Do you know, Lord Husband?”

“Why, no,” said Saxa, frowning. “You’ll build a wooden enclosure in back of the Temple of Venus for your gift to the people, won’t you, Quintus Macsturnas? Or have you engaged the Great Circus? You’d need several thousand animals to justify that, I would think.”

“My gift won’t be that extensive, no,” Macsturnas said with a flash of good humor. “Not for the aedileship, at least. If I gain the honor of the consulate like you, Gaius Saxa, perhaps I can manage something on a greater scale.”

Hedia pursed her lips in silent approval. Macsturnas had asked to accompany Saxa to curry favor with his senior colleague, after all. He must have belatedly realized that boasting about his lineage wasn’t the way to accomplish that.

“Well, when we’re inside, we can ask my son,” Saxa said. “I’m sure Varus will know why it’s built this way.”

“Better that we ask Veturius himself, my dear heart,” said Hedia, patting her husband’s hand to take away any suggestion of sting in her rebuke. “See, there he is in the gateway to receive you.”

The servants leading the procession had fallen away to either side. Varus and Corylus waited with two older men. The elder Cispius would be the one wearing the toga whose border was dyed with the two narrow stripes of a knight.

The other man must be Veturius. The beastmaster’s toga was plain, and he looked as though he’d been used very hard.

Hedia consciously avoided a frown: been used and used himself. The broken veins in Veturius’ nose were surely the result of wine.

“Welcome, noble Senators Gaius Alphenus Saxa and Quintus Macsturnas!” Veturius said. His voice was strong, though it reminded Hedia of rusted metal. “You are most welcome to my establishment, Your Lordships!”

Corylus had a hand on Varus’ shoulder, a silent direction to his mentally distant friend. Hedia relaxed slightly. Corylus would prevent her son from injuring himself in his present state. If Varus suddenly shouted an incomprehensible prophecy, as he had done before, that would be easy enough to brush from the consciousness of social inferiors, Macsturnas included.

But it didn’t remove Hedia’s deeper fear. When Varus had fallen into waking dreams in the past, it had always been a warning of some event that was about to occur.

Some terrible event.

Corylus touched the frame of the gateway, feeling the dryad still present though the wood came from the ancient keel of a broken-up trading vessel. She stirred faintly. Though the sycomore sprite was aged, she managed to smile at him; her eyelids were shadowed with kohl.

Corylus was worried by Varus’ state and still more worried at what his waking dream might mean this time, but there was nothing to be done about those things at the moment. His present duty was to act as intermediary between his father and the pair of senators facing him.

“My lord Gaius Saxa… ,” Corylus said in a clear voice. He and the two veterans were all braced to attention. “Allow me to present my father, Publius Cispius, and his friend Marcus Veturius.”

Instead of bowing—they were freeborn citizens of Carce—Cispius and his friend each saluted by striking his clenched right fist on his chest. If they had been equipped for battle, that gesture would have banged their spear shafts against their shield bosses.

Saxa had stepped down from the consulship after the usual month in office, but he remained Governor of Lusitania and nominal commander of the troops there. Saxa had the right to the salute, though it probably startled him to receive it.

Lusitania was on the rocky Atlantic coast of Europe, closer to Britain than to Carce or to civilization generally. Saxa would never visit it: a younger, fitter, hungrier Knight of Carce was acting as the governor’s representative. Saxa had an antiquarian’s knowledge of Carce’s history, though, and enough patriotism to feel the honor of a salute from two of the men who had held the Republic’s borders against barbarism.

To Corylus’ surprise, Saxa returned the salute. The new aedile, Macsturnas, blinked at the scene.

Of course. Saxa probably couldn’t draft a dinner invitation in an organized fashion, but he would have read lengthy monographs on the forms of military protocol. Varus’ father wasn’t a stupid man, though he was a profoundly silly one.

“Marcus and I had the honor of serving under your cousin Sempronius Mela,” Cispius said. “When he was Legate of the Alaudae, that is. It’s a real pleasure to meet a kinsman of Mela.”

Corylus didn’t let his mouth drop open in amazement the way Macsturnas was doing, but he was certainly surprised. Instead of creating an awkward situation, Cispius—the third son of a farmer in Liguria—was handling the wealthy senator perfectly.

Corylus suddenly realized that his father wouldn’t have risen through the ranks as he had without meeting many noble officers. Some would have been as foolish as Saxa and a great deal less pleasant personally.

“Master Cispius, I’m pleased to meet you,” Saxa said. “And to meet your friend, of course. You’ve a fine son in Master Corylus, a very fine son.”

“We are here to view the scaled monkeys from Africa, are we not?” said the old farmer who had come with Macsturnas. His tone was querulous.

“And who would that be, lad?” Cispius asked, quietly but in a voice that sounded like the growl of a big cat. Corylus might not have understood the words if he didn’t know his father well enough to expect them.

Cispius didn’t have the vinewood swagger stick he had carried as a centurion, but as a child Corylus had met his father’s calloused hand enough times to remember its weight. Cispius had grown plump and softer in retirement, but he could still deal with the likes of Macsturnas’ hanger-on without help or a weapon.

“I’m sure we all wish to see the strange animals, Master Paris,” Macsturnas said nervously, glancing between Saxa—who wasn’t the sort to take offense—and the farmer. “As soon as Lord Saxa is ready to, of course.”

“The aedile’s pet philosopher, I guess,” Corylus said quietly to his father. “And the aedile’s not a particular friend of Saxa’s, but he’s footing the bill for this load of animals.”

“Right,” said Veturius, relaxing. “Not the business of a poor working soldier like me.”

“Till they tell us it is,” Cispius added, but he had relaxed also.

“Well, if you’re ready, Macsturnas,” Saxa said. He nodded to Veturius. “Take us through, my good man. I’m quite interested in what my son thinks of the creatures.”

“Why do you need such walls, Master Veturius?” Hedia asked. “Are your animals so dangerous as that?”

Corylus flinched minusculely. He’d been so focused on Varus that he hadn’t noticed Hedia was at his elbow until she spoke.

The servants had stepped aside as they neared the gate, allowing the principals to come together for the first time since they stepped out the front door of Saxa’s house in Puteoli. Alphena, who must have been at the end of the procession, had joined her parents also. She wore a stony expression.

“Well, they’re dangerous enough, Your Ladyship,” Veturius mumbled, refusing to meet Hedia’s eyes. “But the cages that held the bloody creatures all the way to here ought to hold them now. The problem’s the boys here in the port—aye, and some of the girls too. They’d creep in at night for a lark, don’t you see, if we didn’t have walls like these—”

He slapped the coarse tuff with his right hand. It sounded as though he’d laid into it with a harness strap.

“—to keep them out.”

Macsturnas had leaned close to Paris and was whispering urgently, presumably to forestall another impatient outburst. The aedile had no intention of letting a boorish associate turn Saxa into an enemy.

“Does it matter if a few kids look at the animals before they’re shipped to Carce?” Alphena asked. Varus’ sister was a fairly good-natured girl underneath, though half the time she seemed determined to prove something. She drove herself and everybody around her to distraction when she got frustrated. For now, at least, curiosity seemed to have drawn her out of her earlier bad temper.

“Well, it’s not that, mistress,” Veturius said. “You see, we just keep the rare stuff and the carnivores in here. I’ve got pasture outside the city for the bulk animals, the deer and wild asses and bulls, that sort of thing. Even the ordinary elephants. But when there’s a big load like now, the aisles between the cages here are pretty tight.”

Corylus had seen his father wince, but there was no harm done. Cispius sold perfumes and unguents to upper-class households and thus knew not to call a senator’s daughter “mistress,” instead of “Your Ladyship.” An importer whose clientele was brokers—slaves and freedmen— who handled beast hunts and gladiatorial bouts didn’t normally need to worry about forms of address.

“I don’t see… ,” Alphena said, letting her voice trail off as she apparently realized that interrupting a man like Veturius wasn’t going to get information out of him more quickly. “No, no, just go on.”

Cispius had been the Alaudae’s First Centurion, the legion’s highest permanent officer—directly under the legate whom the Emperor appointed. At that time Veturius had commanded the tenth company of his tenth cohort. In the Alaudae the Tenth of the Tenth was the Special Service company rather than being a posting for the legion’s most junior centurion. It handled raids and patrolling, the sort of jobs that the Scouts did when Cispius became prefect of the 3d Batavians on his final posting.

Scouting and the things that scouting requires take a toll on a soldier even when he retires with all his limbs and not too many physical scars. Corylus was only ten when he moved with his father to the Batavians on the Danube, but even then Veturius drank enough to be noticed in a community of professional soldiers.

“Well, some kid would be poking a stick at the baboons, but he’d jump back when they banged into the bars and a lion would reach out a paw and grab him from behind,” Veturius said earnestly. “Or it might be the other way around, you see? And when there’s a fresh kill like that and blood all over, hell, why, the whole compound screams and carries on all night.”

Veturius surveyed the crowd, noticing the number of attendants for the first time. “Say, Your Lordships,” he said in concern. “You might want to leave most of this lot outside. I don’t mind the trouble, I don’t mean that, but I guess some of these slaves are pretty expensive, right? Believe me, they won’t be pretty anymore if they lean close to look at a leopard and he claws their faces off.”

“I think that’s a fine idea,” Hedia said briskly. “Leaving the servants outside, that is. My daughter and I—”

Hedia nodded regally toward Alphena.

“—are both wearing new garments—”

Hedia extended half of her short cape like a blue silk wing. Alphena wore a similar garment in white, appliquéd with symbols of the zodiac.

“—which we don’t want splashed with blood. Syra”—Hedia’s maid, listening at her mistress’ side—“you’ll stay here with Balbinus and the others.”

“Yes, ladyship,” the girl said. Her face relaxed from its previous look of blank horror. Corylus wasn’t sure that Hedia was really that callous, but her maid obviously found it possible.

Hedia made a gracious gesture with her left hand. The men in the gateway turned together like drilling soldiers and led the way into the compound.

Veturius was that callous: he couldn’t have done his job with the Alaudae if he hadn’t been. After Cispius retired, he had dried his friend out and set him up in this importing business, which had become very successful. But that hadn’t made Veturius the man he might have been without twenty years on the Rhine.

Corylus kept his right hand on Varus’ elbow, using light pressure to direct him. With his left hand he motioned Hedia and Alphena to follow the two senators. The man Paris stepped in front of them.

Paris flew aside just as quickly. The servants of both senatorial households were waiting in the street, but Pulto didn’t take the direction as applying to him. He’d grabbed the old man’s wrist, bent his arm behind his back, and pushed him away sharply enough to spill him in the dust with a squawk.

“Thank you, Master Pulto,” Hedia said, nodding pleasantly. She swept into the compound behind her husband.

What an empress she would make! Corylus thought, then felt a chill in case he might have spoken aloud. That sentiment would mean a number of executions if it reached the Emperor’s ears—and the youth who voiced it would be on the first cross.

The roadway from the gate to the harbor was wide enough for loaded wagons, though the paths between rows of cages were much narrower. Cages of birds and smaller monkeys were stacked two and three high.

Pulto walked beside his master and Varus, whistling something cheery between his teeth. He had obviously reacted badly to hearing some scraggly farmer be disrespectful to his betters. Veterans like Cis pius and Veturius, let alone the senators, were Paris’ betters in Pulto’s opinion.

Well, in the opinion of Pulto’s master, also.

The animal Corylus had heard as they approached now screamed again, louder by far without walls of the compound to muffle it. Corylus looked toward the sound. To his amazement the head and trunk of an elephant were fully visible beyond wheeled lion cages that were eight feet high.

“What’s that?” Corylus said—directing his question toward Veturius but speaking to anybody who might have an answer. “It looks like an ordinary elephant, but it’s bigger than even the ones they bring from India sometimes.”

Everyone in the group looked at him. Saxa’s face went blank, then melted into concern: he must have noticed that Varus wasn’t in a normal state. At least he didn’t blurt something out.

“Your son’s got a good eye, Top!” Veturius said, referring in army slang to his former superior. “Come on over here and I’ll show you. We leave plenty of room around him, though he hasn’t been a problem since we got him off the boat.”

The visitors dutifully followed Veturius past hyenas held four to a cage. There wasn’t room for the beasts to pace, but they watched the humans with hatred that was almost palpable.

Paris didn’t make another attempt to hurry the process, but the look he fixed on Pulto was as angry as that of the hyenas. Pulto was used to civilians hating him; one more wouldn’t be a concern.

Corylus suppressed a smile: like Veturius, he’d formed his sense of humor on the frontier. Paris might feel ill-used, but he’d actually been lucky. Pulto wore hobnailed army sandals, which he would have used if the farmer had actually touched Master Corylus in stepping past.

The elephant’s hind legs were chained to bollards sturdy enough to tie up a giant grain ship; the area in front of him had been left clear. He was huge, more like a building than a creature of flesh and blood.

Though the elephant had the build and large ears of his African kin, Corylus had never seen one of those that was much more than seven feet tall at the shoulder. This monster was well over eleven feet tall, bigger even than the Indian elephants like Syrus, which Hannibal had ridden over the Alps.

“You see… ,” Veturius said. His voice was strong and animated now that he was discussing his importing business instead of wondering how to deal with noblemen. “The ones you’re used to, the elephants we mostly get, they come from near the African coast. South of that’s desert, so of course you don’t get elephants there, there’s nothing for them to eat, right?”

The elephant curled its trunk, raised its massive head, and screamed louder than any living thing Corylus had heard in the past.

“But south of the desert, then there’s more grass and more forest and Hercules knows what kinds of animals,” Veturius resumed as his visitors lowered their hands from their ears. “They’ve got elephants like this as was floated down the Nile from way beyond the First Cataract. And if you come here with me, I’ll show you what else we got, the things I asked my friend Cispius to bring his son to see.”

Veturius, limping as he walked more quickly than he had done earlier in the afternoon, stepped around the elephant’s plaza to a cage on a cross street wide enough for a wagon rather than an aisle. Corylus followed with the others, guiding Varus as he had been doing since his friend went into his dream state.

“Stand well clear, if you will,” Veturius said. “They’ve got a reach that’ll surprise you. They came down the Nile on a barge same as brought the elephant there, straight out of the dark heart of Africa!”

Corylus moved to his father’s side, directly in front of the cage where he got the best view through the close-set bars. They were welded iron, not the usual wood pinned or lashed.

“Here they are, Your Lordships,” Veturius said. “Scaly apes like nothing seen before in the Republic!”

Corylus looked at the four creatures; they met his gaze calmly.

Those aren’t apes, and they sure aren’t men, he thought.

But they might very well be demons.

Monsters of the Earth © David Drake