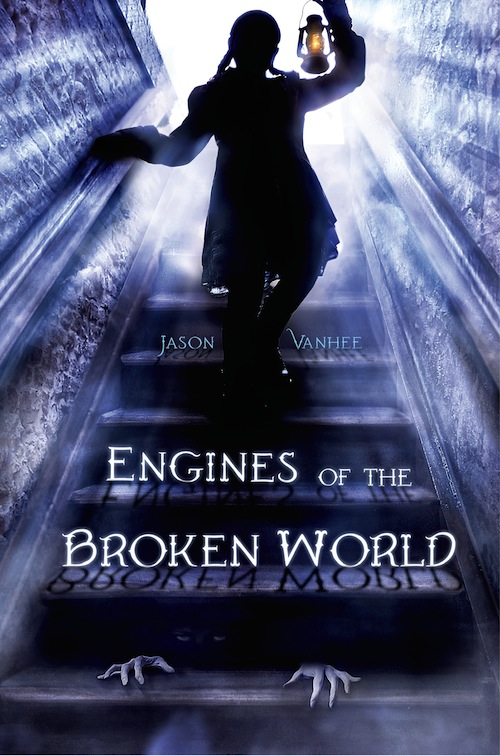

Check out Engines of the Broken World by Jason Vanhee, available November 5th from Henry Holt and Co.

Merciful Truth and her brother, Gospel, have just pulled their dead mother into the kitchen and stowed her under the table. It was a long illness, and they wanted to bury her—they did—but it’s far too cold outside, and they know they won’t be able to dig into the frozen ground. The Minister who lives with them, who preaches through his animal form, doesn’t make them feel any better about what they’ve done.

Merciful calms her guilty feelings but only until, from the other room, she hears a voice she thought she’d never hear again. It’s her mother’s voice, and it’s singing a lullaby…

ONE

It snowed the day our mother died, snow so hard and so soft at the same time that we could neither bury her nor take her out to the barn. So we set her, my brother and me, under the table in the kitchen, and we left her there because we didn’t know what else to do. There wasn’t anyone else to ask, our father dead for years and the village nearly empty and no one to help out two kids left alone in the winter.

Except it wasn’t winter, not really. It was October. Storm like that, with snow like that, we shouldn’t have had till much later, till Christmastime, or even past that more like. But we didn’t spend much time thinking about how the weather had gotten all strange. We just dealt with it.

The Minister wasn’t happy, but then, it wasn’t happy with much of anything these days. There wasn’t much holy going on, and we didn’t pray like we used to, or give it milk to lap up like in golden summertime. The cow had run dry before it died, and the goats were as skinny as fence posts and dried up just like the cow. We didn’t have treats for the little thing the way we would’ve in happier times. But still it yowled and protested when we decided to move Mama away from her bed and put her in the kitchen, which was almost as cold as outdoors, because that wasn’t the way.

“She that bred and birthed you both, and you set her in the cold like that,” the Minister said. It was an old model, a worn-down thing that couldn’t do much more than cavil and complain at us and hadn’t done much more than that, to be truthful, since we were born. My brother just ignored the beast, like he always did, but he was halfway to the Devil, even our mama had said so, and there was nothing more to be done. For me, I felt bad when the little thing hissed its words at us, and didn’t know what all to do about it. Ministers were the word of rightness, and it hurt to not do what it said, but my brother, he had the way of it when he made his suggestion, and I couldn’t disagree with him.

“We got to move her, Merciful,” he said, and I just looked up from crying, because it was a daughter’s job to weep even if you didn’t feel it at all.

“Move her where? It’s cold as sin. We can’t go out.”

He allowed that, and nodded his head even, as if he felt we couldn’t, which I didn’t believe one bit. My brother would’ve mumbled half of a prayer and dragged Mama out himself, if he thought there was a point. With the Minister right there on the coverlet letting itself be seen, though, he knew that he had to do something a little more right than wrong, and that was let himself be led just a bit by his sister.

“Not outside, I guess you’re right. But she’ll go sour here.”

I didn’t say yes, but then, I didn’t say no, and when he took her body under the arms and gestured me to her feet, I took them up and helped him. The Minister paced around our legs with its tail whipping back and forth and said it wasn’t right at all. The kitchen was chill like it never should be, but we hadn’t had a cooked meal in days, since Mama took sick, and most all our wood had gone to the hearth in her room, instead of for stew or bread or what have you. So we laid her out there, under the table, and the Minister padded around her and shook its head at us, and we left her in the dark.

We went back into the bedroom, which was as far from the kitchen as we could get and the warmest place besides. The big bed and our little kids’ beds that slid out of a cupboard were all tidied up, and on the shelf the books that my mother had read to me when I was young were in just the right place, and so were all the clothes and everything else. Except for the bed, where the dent of her body was still warm and the pillow still showed where she had been. The Minister had come with us— always came with us now because there wasn’t hardly anyone else for it to attend to—and settled into the room’s one chair, the rocker that rested in the corner near the hearth. It stared at us with its yellow eyes. The Minister didn’t say anything, but you could almost feel what it was thinking and tell that it didn’t think the best of us, two ungrateful children. And I turned away from its stare, because I was ungrateful, and didn’t regret it, and didn’t want to do anything to make it better.

What Gospel felt I didn’t know. He and I hadn’t ever been close since I was still small enough to suck my thumb and make dolls from sticks. He’d been a wild thing even then, barely wanting to talk to us, barely heeding the Minister, barely sleeping inside the house save when, as now, the weather turned hard and brutal outside or there were things wilder than him around. But I remembered that, when I was very small, he used to talk to me sometimes and tell me things about trees or birds, or about the beasts that slunk by in the darkness and made a meal of anyone so uncautious as to be seen, which Gospel never was. We lost neighbors that way, their houses gaping empty without a body inside, but sometimes there’d be blood spilled on porches or a window broke right out and curtains torn. Gospel knew all the secrets of the beasts and knew how to keep from them. When I was young he tried to teach me, lessons taught in a tongue I couldn’t quite grasp, until about the time Papa died he gave up in frustration and we never much talked after.

Now Gospel was sitting on his little truckle bed, the one his legs barely fit on any longer. His big feet hung over, with his shoulders leaning against my bed halfpulled out from the wall where he sat. His hair was dark and wild, filthy with grease and held back, as much as it was, with a tie of leather from a big cat, one of the things almost safe to hunt, though not to eat. His hands were scarred and dirty, the nails torn where he held them before his mouth, staring blindly out, maybe at the Minister, who stared right back, but maybe not, maybe at the fire instead. Gospel was almost fifteen, near three years older than me, a man or close enough, though there was no one left to say if he was or wasn’t. He was, in fact, The Man, the only one we knew of, though there were still two other women, so I wasn’t The anything. At his belt he had a big knife, with a ragged leather-wrapped hilt, and a gun that didn’t have any bullets but that he wouldn’t let away from himself for any dear thing at all. That gun had been Papa’s, and I remembered the sound it made the last time it was ever fired, when Papa got himself killed by a stranger in a fight six years ago. Gospel’s held it close ever since, for what earthly reason I could never imagine.

He noticed me scrutinizing him, and he shot me a look fierce as the cold wind outside, and then he turned away all at once because the Minister gave a little hiss. Gospel was my brother. He wasn’t supposed to hate me, but I thought sometimes he did, and I think the Minister thought it too.

“You’re each all the other has left,” the Minister said, soft as snow falling against a paper window, barely in hearing above the crackle and pop of the burning wood.

“Don’t think I don’t know that,” Gospel said with fire in his voice, almost settled but not quite yet, still a boy mixed with a man.

“There’s knowing, and then there is knowing,” the Minister replied, and curled its tail up and around to wiggle in the air, with that attitude that it got sometimes to make me want to pull out all its whiskers.

“I know it too well, Minister.”

The Minister only hummed a considering hum and turned to look at me, where I was trying to barely see it out of the corner of my eye, and none too successful at being sneaky like that. “Merciful, do you know as well as your brother?”

“I know. I know he’s all I got, and all I’ll ever have, like as not, the way the world’s going.”

“The world goes as it’s meant,” the Minister said, like it always did if you asked it a question about such things. Furious it could make me, and was coming close now, though it could be kind as well, and it would be, I was sure, once we asked it nicely to do so. It was made to look after us, body and soul, and it would if it could, though what exactly a thing in the shape of a fat gray cat could do to protect our bodies I’d never been sure.

“So it was meant for Mama to die tonight?”

The Minister tilted its head to the side and stared at me. “I suppose you could say it must have been, or else she couldn’t have done so.”

“Don’t even talk to it, Merciful. It didn’t help with Mama all these years; it’s not going to help us now.”

“You don’t know, Gospel. Maybe it knows things.”

“Like what? What do you think it knows?”

“Secret things,” I said, and the Minister hummed and repeated me.

“Secret things,” it said in a sort of hissing whisper.

“I know many secrets, yes.”

“Tell me one thing you know that I don’t!” Gospel demanded, springing to his feet. He stepped around the tail end of the big bed, toward the chair. I stood in the doorway still and didn’t dare to move.

“I know the beginning and end of all things,” the Minister said.

“So you knew our mother was going to die?”

“Everything dies, Gospel.”

My brother shook his shaggy head and turned to me. “Soon as the snow stops, soon as the weather turns again, I’m gone, Merciful. I stayed for her,” he said, gesturing past me to the darkness behind, “but she don’t need me anymore. You can come or not, I don’t mind either way, but if you come, I won’t slow down for you.”

“You can’t leave me,” I said.

“You’ll be leaving yourself, if you want to stay. Anyway, the darned Minister here will help you through it all, just like it helped Mama.” His voice was all sarcasm and bitterness, but then he shook his head again and sighed. “Don’t matter yet, anyhow. The weather’s going to be like this for a spell, I suppose.”

“A long spell, indeed,” the Minister said. Gospel gave it a hard look; but then, he had a supply of those laid up to give to the thing. It paid him no mind and then curled up on the chair and seemed to fall asleep—not that I believed it, and neither did Gospel, I’m sure.

We didn’t say anything for a time, Gospel still standing at the foot of the bed, almost so close that I could’ve reached out and touched him, but so far away that I couldn’t even connect. Then he growled a little and pushed past me into the dark, and a minute later light flared up as I turned slowly around, and there he was, plopped down on the bigger of the two chairs in the sitting room, with the empty doorway to the kitchen framing him from behind and an oil lamp on the table beside him. He didn’t say anything, but he pointed with his first two right-hand fingers at the other chair, our mother’s chair, which was just next to the table. I nodded and went to sit in the little pool of light.

It was silent in that room, with the two chairs in the middle of the chamber; a loom up against the back wall; a chest with spare clothes; and a box that held old wooden toys, most of them carved by Gospel for himself and then given to me when he got too old to bother with them. Not by Gospel; Mama gave them to me in the narrow space when she still cared a bit about the world after he had already quit. There was the big old bearskin rug in front of the chairs where I would sit and do my lessons or knit or whatever it was that I did in all those days that had gone by. Papa got that rug by shooting a bear back when there were still bullets for the rifle, grown rusty and pointless, that hung beside the door. There wasn’t a sound except for a faint pop now and again, and the fainter hiss of snow on the roof, and once, perilous quiet, the sound of a cat yawning.

“So are you coming with me?”

“I don’t know any woodcraft,” I said.

“You’ll learn. Or you won’t, I guess. But there’s nothing here anymore, Merce. Nothing to stay for, no one at all. There’s other places, there’s got to be,” he said, sounding maybe a little desperate, maybe a little defiant. “Places where there are people still. I can find you one and leave you there, and then I can head out on my own and not fret.”

“You wouldn’t fret about me, Gospel,” I said, with more venom than I thought I had in me.

He lowered his face so that the tangles of his dark hair fell over it. “Maybe I wouldn’t. But maybe today I feel like I should, and I’m going to for a bit. How’s that? Go through the motions for you, if you like that better. The point is, I’ll take you away if you come as soon as we can go, and I’ll get you someplace with more people, someplace you can make a life in, not this dead little pit of a village.”

I leaned forward and brushed away his hair, so that he looked up through his thick eyelashes at me. “I don’t know anyplace else, Gospel. How can I live anywhere but here?”

“How can you live here? There’s nothing left. Two goats and four chickens, Widow Cally through the orchard that hardly produces, and Jenny Gone way up the other side of Stony Mountain. The Minister? That’s it, Merciful, that’s all you have here. The Widow’s past seventy, and Jenny’s half as crazy as Mama was, and that’s still saying a lot. You got to come away with me, or you’ll die.”

“I’ll die out there anyways. There’s nobody left out there, either, Gospel. When was the last time a tinker came by? When I was six. I remember because Mama bought me two ribbons for my hair for my seventh birthday. Six years, Gospel, since we’ve seen anyone, unless you’ve seen somebody and never told.”

He lifted his head and swallowed. There was dark fuzz on his upper lip, the mustache he had tried to grow in for months but it never yet came, and it made him look like what he was, a boy trying too hard to be The Man. “I see signs sometimes. Footprints, an old coat in good shape hanging on a stump like somebody just took it off a day before, and once I saw a snare. But no people, no. Nothing like that.”

“So what do you think we can find, Gospel?”

“Something. Anything. There’s got to be someone left. We can’t be all there is.”

And I knew then that for all he played the part of the outsider, he was the one who needed this place, who needed Mama and me, more than I had ever needed him.

“How far have you gone, Gospel?”

“Oh, Lord. Days down the river, and two days up it till it’s just a trickle in the rocks, and over Windblown Ridge, and down past the Hollows. I’ve gone everyplace I could think to go, Merciful, and I’ve seen places where people were once, empty houses and broken roads and graves dug deep back in the forest where nothing could disturb them. Never a soul, though. But they got to be out there, right?” He smiled, a little hopefully, at me, his sister who he hated maybe but needed for certain, and I didn’t have it in me to hate him right then, so I reached out and took hold of his hand.

“I bet the Widow Cally has a map up at her place, and we can look and see where you’ve been, and see where you could go to maybe find somebody. And if you did, we could all go, the four of us, and we could live with them.” Or they could come live with us, but I didn’t say that, even though I didn’t ever want to go from home.

“Do you think she does? I never had the courage toask.”

“Well, you’re the head of the house now, Gospel. Neighbor to neighbor, you can ask her anything.”

He nodded slightly. “Yeah, I suppose I can, can’t I? I suppose I can walk right on up there and ask if she’s got a map, and by the way, our mother’s dead.”

It got real quiet again after he said that, both of us thinking of the thin, sad woman who was growing cold in the kitchen, and all the snow falling so we couldn’t bury her, and how terrible it was to be orphans in the end of the world.

TWO

The dark was well settled outside, and the night far along, when I finally thought to get to sleep. There were things that needed doing, and Gospel, for Heaven’s sake, wasn’t going to do them, nor the Minister obviously, so it was just me.

I had to look through Mama’s things to see what was of value and what of use and what of sentiment, and keep them and then dispose of the rest. A few things might suit for the Widow, or for Jenny Gone on her mountain, and those I set aside. And then there were things that would never do for anyone, old clothes that I had never really seen that were too big for me and probably always would be: for Mama was tall, and I didn’t seem likely to sprout like a vine. Them I had to start to take apart, and set in the chests by the loom, for scraps and for material. And since I was doing that, and since he was here, I set to mending Gospel’s cloak, which was rather tattered, and his jacket, which was worn out at the elbows, and his spare pants, which had raggedy hems and patches of furry skin sewn over the knees. He sat and watched at first, my stitches more clever than his ever were (though he thought himself skilled with a needle), and then after a time he left me in Mama’s chair in the sitting room and went into the bedroom, where the light was grown dim because the fire was almost gone, and I supposed he went to bed.

I was just finishing up on his trousers, which could have used a washing and were thin as onion skin on the seat—about which I wasn’t sure what to do—when the Minister came padding out of the bedroom and settled on the rug, staring up at me. The creature came and went as it pleased, most often here, but sometimes, we gathered, up to the Widow Cally’s. If it ever went so far as Jenny Gone’s, we didn’t hear of it, but then, we didn’t hear much of Jenny at all, her being three hours’ walk away, and Gospel having already learned all he could from her so he didn’t tramp up that way anymore. I tried to ignore the Minister as the little thing stared up at me, but in time it gave up on getting a response without work and just spoke right up.

A Minister’s voice is a strange thing, coming from an animal that you know can’t ever speak on its own. There used to be other cats around, when there were more people, and we used to wonder if the Minister could speak cat talk to them, though that didn’t seem likely. The Minister was a made thing, not born, and so it didn’t meow and croon to the others. They didn’t seem to like it at all, I remember from when I was little; nothing could get the cats to move on like the Minister. For humans it was different, since we liked the Minister just fine, and it was nice as nice could be most often, but it made us feel the guilt of all the things we did that we shouldn’t have, and there’s a lot of that in every life, I guess.

“Your mother is still cold under the table, isn’t she?” the Minister said, soft as almost always, a gentle sweet voice like a tiny bird or a girl child small enough to hold in your arms.

I pulled my thread tight and snipped it off, making a neat little knot of it with my neat little fingers. “What do you want us to do? Go out and catch our deaths?”

“The body shouldn’t be lying there under the table like that. Not at a time like this.”

I looked right at it, into the yellow eyes that stared like nothing else could: not a real cat, not Gospel, and not even one of my old twig dolls that couldn’t move or blink at all. I couldn’t outstare the Minister, but for a minute, maybe, I could make it see I understood. “Minister, it’s cold as death outside, and the snow’s near a foot already and still falling steady, and you want my brother and me, as is just now orphans, to go out and dig a grave? You that’re supposed to help us, that’s what you want?”

The Minister stared right back, though I think it didn’t so much stare as just look, if I’m being honest. It doesn’t manage to blink, or make anything like living responses, most of the time. Made things never could, my mama used to say, but I didn’t ever know quite what she had meant. “The snow will only get deeper, Merciful, and the task only harder.”

“Do you know how long it’s going to snow?”

“A day, and a day, and more than a day more,” the silly thing said, which was Ministerspeak for a long time. But the Minister did have a touch for the weather, and knew it well enough: better than me for sure, and better than Gospel, who thought he was clever (and probably was clever enough, truth be told). So if it said it would snow for a long time, I figured that it was right, and I thought of the body in the kitchen and that maybe we should do something after all. Something, but I didn’t know what. I really didn’t think we could bury it, just the two of us, a not-quite-man and a girl half-grown, in the snow in the dark.

“Can we wait till morning?” I asked. Of course I didn’t want to wait. It was wrong not to bury her, and anyway, it gave me the shivers just thinking about there being a dead body about the place, even if it was Mama. “Probably there won’t be too much snow under the Big Tree, and we can bury her there.”

“Leave her that birthed you to sit and harden till dawn? Ungrateful child, crueler than poison.”

And I felt guilty, yes I did. But there really wasn’t anything at all I could do on my own, and I knew Gospel wouldn’t stir from his bed for anything less than a bear or a catamount or something worse, so it had to be the morning, if I could even convince him then. Morning or not at all, and I couldn’t think of that because, after all, it was Mama lying there, with her toe sticking out of a hole in her left sock and her long painted fingernails crossed on her chest and her face under our best tea towel.

The Minister waited a silent moment until I turned away from its yellow gaze. I used to be a good girl and do exactly what it said and what it told me, and it liked me better then, I gathered. But since Mama got so sick and I had to be in charge more often than not, I started to feel like it was just bothering me. Only I hated how its eyes staring out at me still could make me feel guilty. More than that, I desperately wished to have someone to tell me what to do—even a preachy little cat what I’d been growing more used to ignoring with every passing year— but it wasn’t as easy as all that anymore. The Minister stood up and stretched, for a moment almost what it seemed, and paced purposefully past the chairs and into the darkness of the kitchen. I couldn’t hear it, so quiet was its tread, or see it in the dim and flickery light of the lamp, so I just waited with Gospel’s pants in my chilled fingers and a needle thrust into the arm of the chair and a spool of Mama’s perfect thread on the table beside me, along with a teacup filled with melting snow that Gospel had fetched me when I was working.

It came back and settled down again. “She’s growing hard and almost as cold as outside, Merciful. And tomorrow she’ll be harder yet, and a load to maneuver. But if it can’t be helped, it can’t be helped, and dawn is better than dusk, tomorrow better than never.” That last was another Minister phrase, one that didn’t get much use, but I knew it still. The Minister hopped up to Papa’s old chair and breathed two long breaths onto my teacup, and the snow melted and grew to steaming just a little. I drank it down and said thank you kindly both because it was the polite thing for me to do and because I really was grateful to get a little warm into me. The Minister didn’t do things like that often.

“You should sleep now, Merciful,” the little thing said, and went back over to the kitchen doorway, where it settled down facing into the dark room. Its gray tail swept back and forth, almost like that of a normal cat. I finished the hot water and set down the cup. The pants were just about the best I could do, so I folded them up and put them aside and tucked the needle and thread carefully into Mama’s sewing kit. I supposed it was mine now, though that didn’t seem right. And still the Minister just sat, staring into the dark, the tail always moving, so that for a moment I thought maybe it was nervous; only that was silly, because a made thing couldn’t get nervous.

The light was poor and ruddy in the bedroom, but bright enough to see that Gospel had taken over Mama’s bed as someone should have, but it might ought to have been me, since I’d been here all the time taking care of her and he hadn’t. But he was older, and anyway, he got to the bed first. Probably he wouldn’t stay to use it long, but then, I supposed neither would I, and the bed, the entire house, would go to rot and ruination like so many other places around here.

I tugged out my bunk, the upper one, and then flipped down the supports that my father had built so long ago that I couldn’t remember it. The lower bed in the cupboard was bigger, and I was only just still able to sleep in my own. I should probably have moved to Gospel’s like he moved to Mama’s, but it smelled like my brother, all farts and sweat and greasy hair and wild things, and I hadn’t had any time to air it out, so I just hopped on up into my own bed.

“Did you shut the door?” Gospel whispered.

I hadn’t, because we almost never did, not since Papa died and the big bed just became a bed, not anything else ever. “No. Why would I?”

“The Minister’s out there, not in here, right?”

“Yeah,” I said. I wiggled into the quilts and worn sheets that made up my bedding, not caring to climb back down for Gospel’s silly idea, whatever it was. Turned out I didn’t have to, because he rolled out of bed suddenly and bounded to the door, throwing it shut in a flash. Beyond, I heard the scrabble of claws on the floor, then scratching at the door.

“The Minister wants in,” I said softly. In the dim light, I could barely see Gospel, could barely tell he was pacing over to my bedside. His shoulders and head were above the level of my body, and he rested one hand on the frame that held my mattress.

“I know it does. That’s why I kept it out. It wants to hear everything we say, Merce. And maybe I don’t want it to hear every word I’ve got to say to you.”

“You already said you want to run away while it was there, right in front of us. What’s worse?”

He breathed out slowly, completely. “There is worse, Merciful. And I got to tell you, because I can’t tell anybody else. And I don’t want that made thing to hear, because who knows why it was made?”

“It was made to keep us on the righteous path, the path of goodness, and to tend to us, body and soul.” It was what we were taught, and it was what I was supposed to say, and I even think I believed it, most often.

The scratching was almost frantic now, but the door was sturdy wood, and there was no way the Minister was going to get in.

“Come and sit on the bed, away from the door, and we’ll talk. I got a lot to tell you. You’re clever, Merciful, and I want to hear what you think.” He stepped back and flopped onto the big bed, crawling over and away toward the headboard, and then settled down where the light was a tiny bit better, sitting cross-legged, with his hair falling into his face like it always did.

I didn’t want to move, finally getting a little warm, and not wanting to hear whatever cockamamie nonsense Gospel was about to spew out. But he was my brother, and my mother had just died. I had no one else, so I went to listen to him speak, quilts wrapped around my shoulders, on the bed that was almost still warm from the dead woman.

Engines of the Broken World © Jason Vanhee, 2013