The aliens landed in a New Jersey discount store when I was five years old—materializing on the shelves without even a flashing blue light. They had eerie, iridescent armor, and were a sort of United Nations of the rest of the solar system—one being each for seven of our planetary neighbors. In their clone-like multitudes they waited in form-fitting plastic pods, glued to cardboard covered with pictures of their home planets and narratives of their lives before arriving on our world. And there was no way I wasn’t going to help them fan out through all of suburbia. Child turned against parent, and one by one The Outer Space Men colonized my playroom.

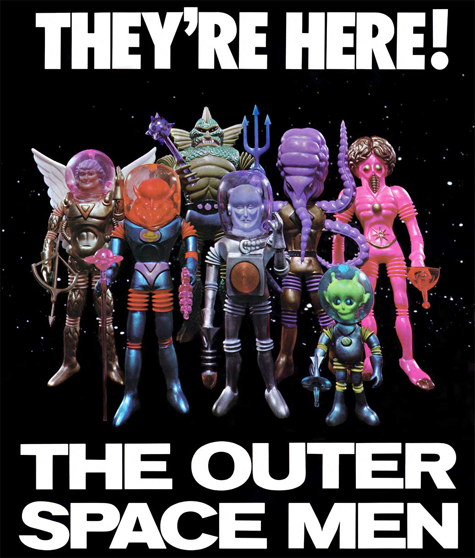

The Outer Space Men were bendable rubber action figures conceived by toy-designer Mel Birnkrant, a departure for the company Colorforms, then primarily known for adventures in two dimensions—sets of self-adhesive flat-vinyl shapes (like a superhero in different poses) that could be stuck and restuck on some designed plastic background (say, the city the superhero was swinging through) in multiple combinations.

The Outer Space Men capitalized on the highest tech of the times, feeding the frenzy for space travel when the Apollo program was still new. The toys were marketed from 1968 to the very early 1970s, then disappeared. In those days of a single pop-culture pipeline (and no all-seeing eye of eBay as backup), things could appear and disappear from stores so quickly that you’d later think you must have dreamed them. The Outer Space Men would occasionally phase back in as I grew up, as tiny prizes in gumball machines, as keychains in hipster novelty stores, like the fleeting resurfaced memory of an alien abduction.

But in the era of niche ephemera we now occupy, everything pops back out of the wormhole eventually. Wall Street whiz Gary Schaeffer found his way to Birnkrant, still imaginative and irreverent and undefeated decades later, and the two have been licensing new versions of the Outer Space Men toys to the 21st century compulsive-collector market. There’s also a fascinating graphic novel by Eric C. Hayes and Rudolf Montemayor, which is garnering serious Hollywood interest in what could be the next Transformers or G.I. Joe.

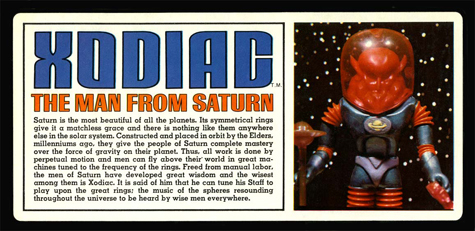

Or more accurately, a Transformers or G.I. Joe for a less mainstream audience. When The Outer Space Men came out, they were like the counterculture companion to Mattel’s more high-profile “Major Matt” line of astronaut figures and moon-roving vehicles based on the reality of the U.S. space program. But reality is not where kids want to play. And while Major Matt took a few years to even get an African-American crew-mate, The Outer Space Men were fantastically diverse from the beginning. Electron+, the blue-skinned Mr. Freeze-esque man from Pluto; Astro-Nautilus, the squid-tentacled (and tentacle-nosed) man from Neptune, who looked like some kind of aquatic Ganesh; Orbitron, the hot-pink, external-brained man from Uranus; Xodiac, the benign satanic-looking man from Saturn; the reptilian hulk Colossus Rex from Jupiter; Alpha 7, the little green man from Mars; and Commander Comet, a purple-haired angel from Venus. There was no man-from-Mercury, which kept planet-mapping dweebs like me up at night. And of course no women-from-anywhere, though my sister adopted Orbitron as “a girl” because of his color-scheme, making these toys mean more, to more people, than their own creator could foresee.

And it turns out Mel Birnkrant was one of the earliest pop meme-merchants. Electron+ not only reminds you of Mister Freeze but is a close cousin of 1950s B-movie monster The Man From Planet X; Orbitron takes off from the Metaluna Mutant in This Island Earth; Alpha 7 could be deserting from the Invasion of the Saucer Men, and so on. My teenage self delighted in the kind of copyright heresy that would become central to the creative-recombination and cultural-property wars of the hip-hop/mashup era, and Birnkrant just as freely celebrated the sources of his re-inspiration when I spoke with him at New York Comic Con this year.

Schaeffer sets up a mobile museum of Outer Space Men memorabilia at such gatherings for superfans and new followers to gape at, and seeing Birnkrant among his treasures was like meeting the Geppetto of my own lifetime transformation from regular boy into professional geek. Birnrant was classically trained, and thought he was going to be a painter; he brought more of those refined techniques to his toy-making than he gives himself credit for.

“I flipped through a bunch of Famous Monsters magazines,” he said of his process in designing the original toys. “In those days you’d pay to sit through an hour and a half of this crappy movie for the one minute at the end where you get to see a blurry shot of this monster you’ve been waiting for. Fan magazines would find the one existing still shot of it.” Birnkrant filled his head with these shots and then went to his drawing-board, reinventing the characters like some cosmic police composite-sketch artist.

He came out with scores of them, and both he and the co-founder of Colorforms—as if by subconscious celestial suggestion—picked the same seven. By the time of the figures’ legendary second set of characters, prototyped but never mass-produced (and miraculously visible behind Schaeffer’s glass cases), Birnkrant had the confidence to create straight from his head, and we might be living on a very different planet if these surreal creatures had found their way into millions of impressionable kids’ rooms. The first set were widely popular, and Birnkrant insists his output just followed where the market was directing, but he’s really describing how the demands of commerce can pressurize gems of creative resourcefulness.

My storytelling future-self was drawn to the fledgling transmedia of the short texts that appeared on the backs of the Space Men’s packages, strangely poetic thumbnails about the figures’ uncanny origins and wondrous environments and lonely missions in the stars. “Took me about as long to write them as it does to read them,” Birnkrant told me. “I filled my head with a lifetime of clichés and references and these came out.” As to the turns of phrase in some of them, like the never-released Cyclops’ single, Hindu-deity-like optical organ “seeking more than meets the eye,” Birnkrant said, “A lot of it was a joke but some of it still gives me chills.” Me too, because clever wordplay is the kernel of both humor and prophecy, and his toys made the scary frontier of off-world exploration seem more fun than foreboding.

The Outer Space Men also made contact with major institutions of influence and principal representatives of Earth in my stranger-than-science-fiction childhood. My second-grade teacher agreed to get us interested in astronomy by holding an art contest to design the (then-unmarketed) Man From Mercury, with prizes including space-science books donated by my dad. When I had a chance to meet Mercury/Gemini astronaut Gordon Cooper I thought it a good idea to bring my Outer Space Men toys, which he critiqued thoughtfully, suggesting that the real-life atmospheric pressure of Venus should make the svelte Commander Comet look more like the beefy Colossus Rex, etc.

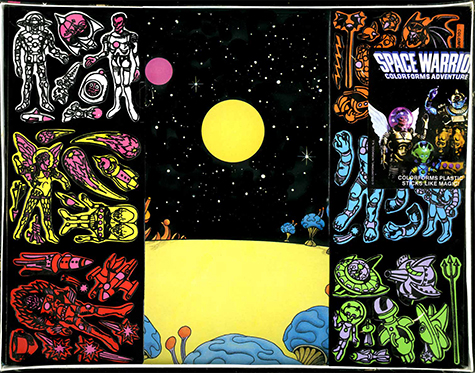

But in the end, The Outer Space Men were subject to some lower powers controlling their fate. A perceived fall-off in the fad for space toys (no actual aliens were out there waiting for Cooper and his comrades) caused the proposed second series to be renamed “The World of the Future,” then a dock strike near Christmastime made distributors back away. The debut of the first Star Wars flick sparked a partial revival: a new edition of Colorforms’ vinyl-collage kits featuring images of miscellaneous Series One and Two characters were released under the new name “Space Warriors.” Birnkrant also hand-Photoshopped hybrids of the dioramas he had staged for the original action-figures’ packages, cutting and pasting them together for a few kids’ puzzles that showed up in department stores’ toy sections and which, for over-excitable preteens, enhanced the legend of the first series’ sequel somehow having existed while we weren’t looking.

Decades later Schaeffer met up with Birnkrant to bring back the The Outer Space Men, contracting with specialty toy companies to finally bring out the “lost” series of figures, in addition to reissues of the original designs and updated versions of the classic set. The figures, plus a set of geek-chic tee-shirts, the graphic novel (with maybe another to come), and, hopefully soon, a big-budget movie will reintroduce audiences to the most dynamic sci-fi franchise no one remembers—the original “guardians of the galaxy.”

“I was not an inspired individual expressing his inner being,” Birnkrant emphasizes. “I was doing what it took to make a living.” Even if I believed that, what matters to pop history is that he seemed to express the inner beings of his figures’ misfit admirers. And in the process, helped us find our purpose. “You’re as grown up as you’re going to get,” he told me, “when you realize you’re never gonna grow up.”

Adam McGovern’s dad taught comics to college classes and served as a project manager in the U.S. government’s UFO-investigating operation in the 1950s; the rest is made up. There is material proof, however, that Adam has written comicbooks for Image (The Next issue Project), Trip City.com, the acclaimed indie broadsheets POOD and Magic Bullet, and GG Studios, blogs regularly for HiLoBrow.com and ComicCritique and posts at his own risk on the personal site Fanchild. He lectures on pop culture in forums like The NY Comics & Picture-story Symposium and interviewed time-traveling author Glen Gold at the back of his novel Sunnyside (and at this link). Adam proofreads graphic novels for First Second and Holt, has official dabblings in produced plays, recorded songs and published poetry, and is available for commitment ceremonies and intergalactic resistance movements. His future self will be back to correct egregious typos and word substitutions in this bio any minute now. And then he’ll kill Hitler, he promises.

I had these when I was a kid. Loved them, but the internal wires tended to break too easily. Still a great toy. I believe I had the whole set at one time.

Adam

Fantastic article! If I knew you were interviewing The Man, I wouldn’t have tried to monopolize so much of his time at NYCC!

Thanks for sharing the OSM history and yours!

@Tad Ghostal, I’m not sure The Man knew it either so no worries :-) — no, he knew I was a newshound but I was keeping it informal since he’s a genius of conversation and all participants helped me paint the picture; great meeting you and thanks for the kind words and *shared* history!

@Kmyatsuhashi: Yes, those internal wires only lasted a few bends, it seemed, before they broke… I remember that well.

I also remember that the other toys you mentioned had the full name of Major Matt Mason. I had those too, one of the books that sold around them, and the space station and glider… it was a bit more than “reality,” and it always surprised me that MMM didn’t do better before it folded.

Fantastic Article Adam. Thanks so much for covering the OSM. Best regards, Gary.

Thanks to you and Mel for helping the dream land back in our world, @Gary B Schaeffer. @Futurisk, those wires were what made me go through generations of Alpha 7s and Colossus Rexes like serially-named pet dogs or cats :-) — an additional bonding exercise. (In fairness, my Lakeside brand Captain Americas wore out faster, and that was the old flat-construction model, whereas Mel’s stuff was revolutionary in being fully formed but still movable.) And of course you’re right about Matt Mason’s full name; I’ve just had more years of listening to “Space Oddity” than I ever did playing with those toys so “Major Matt” is how I remember him :-). You’re also right that Matt set a course farther from reality as he went along, though not usually into imagination as good as Mel’s for my tastes. The only Mason toy I ever felt was fully fit to polish the Outer Spacer Men’s boots was Scorpio, and that was practically when the whole line was marooned for good anyway. I’m glad Scorpio went on to have a good rap career after that, though. :-)