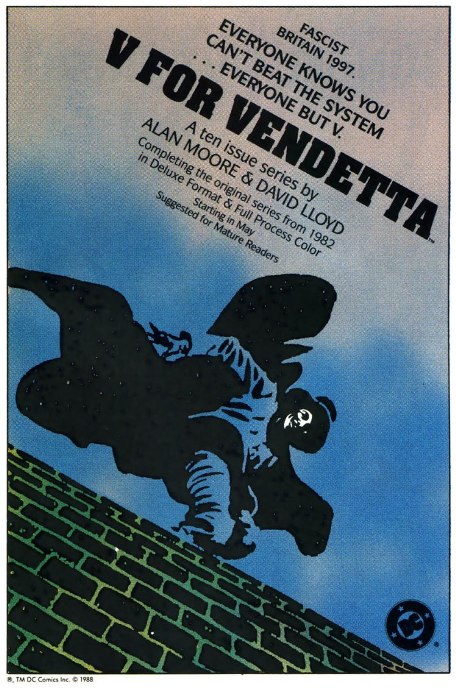

It was 1988. I was 12 years old, squeezing through the crowded and cluttered aisles at Little Rock’s only comic store, when I saw a poster of a cloaked, chalk-faced figure running across the top of a wall. The copy on the poster read:

FASCIST

BRITAIN 1997.

EVERYONE KNOWS YOU

CAN’T BEAT THE SYSTEM

…EVERYONE BUT V.

V FOR VENDETTA

A ten issue series by

ALAN MOORE & DAVID LLOYD

I’d never seen such a thing. My comic book buying in those days was exclusively of the Batman, Captain America, and Green Lantern variety. I didn’t know what “fascist” meant, had no idea who Moore and Lloyd were, and had no good reason to want to collect a ten issue series of English comic books.

But something in the stark imagery of the poster appealed to me. (It was around this same time that I discovered the 1950 Edmond O’Brien flick D.O.A, which kicked off my love of film noir, so maybe I was just ready to take a plunge into a certain kind of dark crime story. Or maybe it was something in the Arkansas water.) I went back a week later and bought issue one.

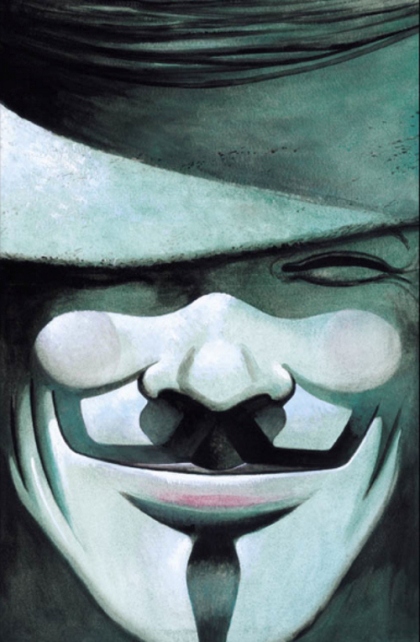

V For Vendetta was over my head. It told the story of a young Englishwoman named Evey Hammond, living in a dystopian London ruled by the fascist government of Adam Susan, aka The Leader. A rightwing despot who came to power after a nuclear war destroyed most of earth’s other major powers, Susan rules his subjects under strict codes of racial, religious, and moral purity. Seemingly all-seeing and all-knowing, the government is corrupt, vicious, and inescapable. Into this hellscape comes a caped stranger wearing a Guy Fawkes mask, wig and hat. He kills some government goons (known as Fingermen) who are trying to sexually assault Evey, and then he whisks the girl away to a secret domain he calls The Shadow Gallery. An underground compound, The Shadow Gallery is filled with forbidden art and books and music and movies. It seems, in fact, to be the final collection of an eradicated culture. It’s like the Batcave if Batman were a gay theater major turned domestic terrorist.

I don’t make the gay reference casually, or to get a cheap laugh. One of the things that flew over my head back in 1988 was the extent to which V For Vendetta was an angry screed from a side of British politics and culture that had seldom been heard from, and I had no idea the extent to which that message was bound up in a furious reaction to the rise of rightwing politics, anti-gay policies, and indifference to the AIDS epidemic. Evey’s caped savior calls himself V, and he’s out to dismantle the government:

Evey: That’s very important to you, isn’t it? All that theatrical stuff.

V: It’s everything, Evey. The perfect entrance, the grand illusion. It’s everything. And I’m going to bring the house down.

V For Vendetta was an immediate hit with serious comic book fans. The late eighties was some kind of second golden age of comic books. Crisis On Infinite Earths, Watchmen, The Killing Joke, The Dark Knight Returns, Batman: Year One, Man Of Steel, Todd McFarlane’s run on Spider-Man—every few months seemed to bring some landmark classic that helped redefine comics as most people knew them. Even among these titles, though, V For Vendetta stood out as something different.

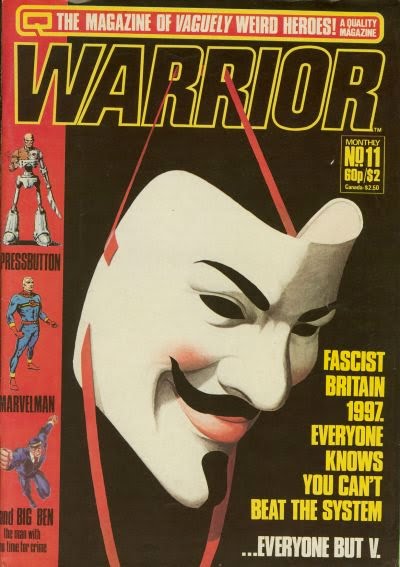

The book had its origins a few years prior, in Warrior, an anthology comic in England. Appearing in stark black and white, V For Vendetta was serialized and soon became the comic’s most popular reoccurring feature. When Warrior was canceled before V could complete his mission to blow up Parliament, DC Comics brought the series to America, let writer Alan Moore and artist David Lloyd complete their run, and added new material including new pencils by Lloyd and Tony Weare, and muted colors by Steve Whitaker and Siobhan Dobbs.

The resulting book is, in every sense, a graphic novel. Broad in scope, with a large cast of characters, it is really Evey’s story—the story of a lost and lonely young girl who embarks, unknowingly, on the hero’s journey. Left an orphan when her activist parents are hauled off by government thugs, she finds herself in the company of a kind but scary stranger, a superhuman man in mask who talks in riddles and kills other human beings with disturbing ease. The person Evey becomes by the end of the book in not simply a carbon copy of V. She’s a woman and a revolutionary.

V himself begins and ends as a mystery, a man behind a mask, a performance. We never fully learn his story, only that he was taken by the new government to a concentration camp where he was used—along with other undesirables—as lab rats in a series of experiments. The government didn’t get what it expected.

The 2005 film adaptation of the book helped popularize V as a symbol of resistance—leading to the establishment of the Guy Fawkes mask (really the V mask at this point) as an instant icon of anti-government feeling (or rather, a certain flavor of ant-government distinct from the Tea Party flavor)—but while the film has its virtues, it also rewrites much of the book. Many of these changes are for understandable reasons. A condensed plot point here, a deleted subplot there. But other changes, like a late-in-the-film ham-handed attempt to build a love story between V and Evey, actually work against the emotional core of the story. V can’t be both mentor and would-be lover—he ends up as a rather awkward combination of Obi-Wan Kenobi and the Phantom of the Opera. Interestingly, though, the film retains most of the book’s radical politics. The film is still a pretty subversive work—it still ends with an act of terrorism celebrated as a heroic call to arms.

Alan Moore is one of the great grumpy geniuses of our modern culture, and V For Vendetta is the result of his deeply held political convictions. Asked if he considered himself an anarchist in an interview in 2007, he responded:

[A]narchy is in fact the only political position that is actually possible. I believe that all other political states are in fact variations or outgrowths of a basic state of anarchy; after all, when you mention the idea of anarchy to most people they will tell you what a bad idea it is because the biggest gang would just take over. Which is pretty much how I see contemporary society. We live in a badly developed anarchist situation in which the biggest gang has taken over and have declared that it is not an anarchist situation—that it is a capitalist or a communist situation. But I tend to think that anarchy is the most natural form of politics for a human being to actually practice. All it means, the word, is no leaders. An-archon. No leaders.

V For Vendetta remains as fresh and fascinating as the day it appeared at my local comic book store. It’s one of the truly indispensible graphic novels and one of the best books, period, of the last 25 years.

Jake Hinkson is the author of the novels Hell On Church Street and The Posthumous Man. He blogs at The Night Editor.