In 1934, the East Wind blew Mary Poppins, a thin woman with an upturned nose, small blue eyes and shining black hair right into the house of the not that well to do Banks family. Initially, everyone is delighted: Mr. Banks because he has just saved some money; Mrs. Banks because Mary Poppins is so fashionable; the servants because it means less work, and the children, because Mary Poppins not only slides up banisters (apparently having no interest in the cardiac benefits of climbing the stairs) but also administers medicine that tastes utterly delightful.

The rest of the world, particularly an enthusiastic movie producer named Walt Disney, would soon be delighted as well.

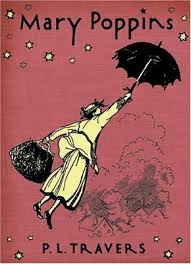

Mary Poppins was the brainchild of Pamela Travers, an Australian-born actress/writer by then living in London. (She was born Helen Lyndon Goff in 1899, but later changed her name to Pamela Travers, the one I will be using for this reread.) As with so many other successful children’s writers, she started telling stories at a very young age to enthralled siblings. Mary Poppins was her first major success.

The book is set in a decidedly middle class household in some vague pre World War I period. I say pre World War I, since although the illustrations, especially of the clothes, suggest a later date, the world of Mary Poppins is remarkably free of cars and telephones. Maybe technology just vanished in Mary Poppins’ commanding presence.

If the timeline is a bit vague, the family’s finances are not: we are told that although the family has enough money to employ four servants (a cook, a housemaid, a boy, and a nanny), they do not have much beyond this, and that number of servants places them firmly into the middle-class money bracket: many middle class families in Victorian England through the 1930s tried to keep at least one servant to help with the then overwhelming amount of housework necessary in the pre-appliances age, to the point where servants were considered a mark of respectability.

And, as the text makes clear, the Banks have not exactly hired superior servants, either: Mrs. Brill is described as not much of a cook, although she has a kindly heart; Robertson Ay spends most of his time asleep or messing up the household shoes. Only Ellen the housemaid seems vaguely competent, although given the amount of time both Mary Poppins and Mrs. Banks end up spending on household chores such as dusting, laundry, and shopping, her competence, too, might be questioned. In later books she develops allergies and starts moping after a policeman, becoming steadily more useless; perhaps it’s just that Mary Poppins, for all her sternness, is better at bringing out the worst than the best in people-or at least adults. Their nannies have not been much better, which is why Mary Poppins gets blown in.

Sidenote: ok, having the nanny arrive by wind is kinda cool, but otherwise, bad form, Ms Travers, to start the book with a description of how to reach Mary Poppins’ house. Bad form. First, you just sent millions of kids off searching, and second, did you ever think that maybe, just maybe, the other inhabitants of Cherry Tree Lane are dealing with quite enough, thank you already, what with various mysterious Happenings and Arrivals, without you sending gangs of children up and down their street loudly searching for Mary Poppins? Even imaginary neighbors on imaginary streets deserve better than that. Manners, Ms Travers, Manners.

Interestingly, the first thing Mary Poppins does after her arrival is immediately desert the children and go out on a day off, this right after intimidating Mrs. Banks into giving her extra time off. Interestingly, because the main thing I associate Mary Poppins with is, well, being a nanny and thus spending time with children. In later books, in fact, Jane and Michael do manage to follow along on Mary Poppins’ not so little excursions, following her on every Day Off, but here, Pamela Travers firmly establishes Mary Poppins as an independent adult person perfectly capable of having magical adventures of her own.

Also interestingly, it’s not at all clear if this adventure—walking directly into a sidewalk painting—happens because of Mary Poppins, or because of the man she is sorta dating, Bert. (Travers would later attempt to deny that the two had a romantic relationship, but come on: they are meeting each other for tea and stepping through chalk painting to have magical teas together. This is more than the usual result from your average OKCupid connection.) I say “not at all clear,” because by the very next chapter, and in the subsequent chapters, it is quite clear that Mary Poppins is not just magical in her own right, but can actually do magic, however fiercely she might deny it. She can talk to animals, make tea tables float to the ceiling, send people on whirlwind visits around the world, and clean things with a touch of her hand. In this chapter, however, this all seems muffled. She also seems like a very sweet, kindly, person.

But by the next chapter, the classic image of Mary Poppins emerges—classic from the books, that is, not the movie. (We’ll get to the movie. For now, the book.) This is a Mary Poppins who is not just superior, but sometimes actively rude about it; haughty; often acerbic; not just easily insulted, but quick to insult her charges, and who can be, frankly, rather terrifying. It’s not that I have any real fear that anything terrible will really happen to Jane and Michael and John and Barbara, but the children definitely think that possibility exists, and given Mary Poppins’ extensive magical powers, they may have a point. And Mary Poppins can be cruel, and, despite all of her claims to respectability and polite behavior, even, on occasion, rude. This is also a Mary Poppins who is offended by the mere idea of a mere Butcher expressing an interest in her, even though in the second chapter she was perfectly content to go on a date (yes, Ms Travers, it’s a date!) with a mere Match-Man.

The emergence of this sharper, fiercer and much more entertaining Mary Poppins happens during a visit to the home of Mary Poppins’ uncle, who is filled with Laughing Gas because it is his birthday. Mary Poppins, who up until then was a blend of mysterious and kindly, with no more than a hint of sternness and pride, starts snapping at her uncle and the children, an attitude she retains for the rest of the book.

The shift in tone is the result of a writing gap: a slightly different version of the second chapter had been published in 1926—eight years before the appearance of the book. Or, if you want a more magical version, we can handwave this by saying that Bert the Match-Man is not only slightly magical in his own right, but also has the ability to change Mary Poppins’ basic personality.

The rest of the book follows the pattern that the other books would follow. I say books, not novels, because Mary Poppins, outside of those first two chapters, is more of a collection of short stories centered on Mary Poppins and the Banks children than on any overall plot or character development. The stories include Mary Poppins telling a fairy tale about a red cow who manages to catch a star on her horns, leading to all kinds of complications and a metaphor about fame and art and clinical depression; Michael having a Bad Day (in other words, misbehaving in typical five year old style); a visit to the rather terrifying Mrs. Corry and her two daughters, who later put stars in the sky; and celebrating Mary Poppins’ birthday at the zoo.

Many of the stories are delightfully fun and full of magic. But rereading it now, what I think most surprises me about this book is—the first two chapters and a later interlude outside St. Paul’s Cathedral aside—just how mean it is, and just how much time everybody spends yelling at everybody else. For instance, the mysterious Mrs. Corry has terrified her two daughters into both obedience and clinical depression; she humiliates them right in front of Jane, Michael, and Mary Poppins. A pampered dog first terrifies poor Miss Lark, then forces her to adopt a second dog of very low origins indeed (Mary Poppins, who speaks dog, helps out), something that greatly distresses her—although in later books we do learn that she’s adjusted to both dogs.

But the real cruelty comes from Mary Poppins. Initially, she comes off as simply strict, but this later turns into what almost seems like borderline abuse. She yells at Jane and Michael when they try to tell the truth—more than once—and even tells Michael “that the very sight of him was more than any self-respecting person could be expected to stand,” which, ouch. She was to get still worse in later books, but even here, she can be terrifying.

Which in some ways makes her all that more comforting: no matter what happens, readers know that Mary Poppins has the strength and character to deal with it, since she will absolutely not tolerate anything she considers wrong. And this in turn means that she can be trusted to protect her young charges. As terrifying as the moment when Michael grabs a magical compass, summoning infuriated creatures (including, in the expurgated edition, an infuriated panda bear, which is perhaps…not quite as terrifying as it should be), the second Mary Poppins arrives on the scene, all is safe.

And Mary Poppins can be unexpectedly kind, not just to her young charges, but also random stars that decide to do a bit of Christmas shopping for others, but fail to get a random present for themselves: Mary Poppins hands over a pair of very fine fur lined gloves as a present.

The star chapter was my favorite chapter when I was a child, and perhaps not surprisingly, the only chapter I remembered clearly: something about the idea of stars coming down to dance and do Christmas shopping and pick up books and spinning tops and jump ropes is just too marvelous to forget.

Perhaps the idea is to reassure children that they can feel safe, even when they feel terrified, or that it is safer to be with a competent adult—and whatever else Mary Poppins may be, she is certainly competent—than with an incompetent one, however kindhearted and silly. After all, Miss Lark’s kindly overindulgence has made her dog miserable; Mary Poppins’ stern rules and strict upbringing has brought magic to the children. And that, of course, would be the other idea: even in the most humdrum, ordinary places, magic can still exist.

One note: the ebook library edition I just read was based on the First Harcourt Young/Odyssey Classic edition of 1997. In other words, it’s an expurgated edition, marked as such with a chapter heading called “Bad Tuesday: Revised Edition.” Thanks for clearing that up, First Harcourt Young/Odyssey Classic.

The revisions were written by Travers herself. In the original version, which was the version I first encountered while living in Italy, Mary Poppins and the children go round the work with a magical compass, encountering stereotypical Eskimos, Native Americans, blacks (who speak nonstandard English and eat watermelon), and Chinese people. In the 1981 version, Mary Poppins and the children instead encounter a Polar Bear, Macaws, a Panda Bear, and a Dolphin, who all speak standard English. Given the description of where the dolphin is and what it is doing, it should really have been a California sea lion, but this quibble aside I find the revisions a decided improvement on the original.

Travers later defended her racial stereotypes and occasional bits of racist language in the books by commenting that the children who read the books never complained. That might be true, but it is equally possible that child readers (me) didn’t understand what they were reading, or never thought to question an adult about it, or were unwilling to talk to an adult about it, or, like many readers or viewers today, chose to enjoy the books despite any problematic elements. It’s also true that these descriptions are one reason why my local libraries in Illinois continued to ban all of the Mary Poppins books even after the revised edition was released.

Several libraries still have copies of the original edition for interested readers; parents may wish to check which edition they have before reading the book to or with their children.

I should note that these descriptions didn’t quite go away—we’re going to have another little chat when we reach Mary Poppins Opens the Door. But first, we have to watch as Mary Poppins Comes Back.

(No, my segues haven’t gotten any better. Were you really expecting them to?)

Incidentally, so we aren’t all shocked about this later: I plan to do posts only on the first three books, since the rest of the Mary Poppins books are for all intents and purposes just short, filler short story collections.

Mari Ness has never stopped looking for random falling stars while shopping. She lives in central Florida.

Members of the privileged, labour-employing minority always complain the servants are lazy and incompetent: the alternative would be to admit that they weren’t overpaying them.

And they’re always so poor they can only just afford their lifestyle.

I was surprised to find out that Travers, among many other things, was a Theosophist. It makes more sense to me to think of Mary Poppins as the Banks children’s guru. She’s Tough Love personified.

Also, British culture in general was not exactly cuddly with young children at that time period.

Well, I enjoyed the books a few years ago, so this should be fun. Mary is quite possibly one of the most powerful non dieties in fantasy literature.

I loved the Mary Poppins books. I am decidedly not impressed with what Walt Disney did in the movie. Basically I liked ascerbic, difficult decidedly not cuddly Mary Poppins.

I only investigated the books after a re-watch of the movie as an adult, and although the imaginative content was good I was repulsed by the unneeded nastiness of the heroine [as opposed to the useful and necessary ability to cut through nonsense and protect the helpless.] As for the movie, it was fun [and less vicious], but only as an adult did I take note that the events therein seemed to span only a day or so, and it seemed cruel to make her visit that short.

I just re-read the series, having seen the recent Saving Mr. Banks. I enjoyed them, but Ms. Poppins is definitely on the drill sergeant side of things. i also found annoying her tendency to deny that magic happened, so was glad that Jane and Michael could always prove themselves right by noticing her earrings or sun’s kiss, etc.

I would say that Mary definitely ‘magics’ the date with Bert- he has only earned a couple of pennies that day.

@3 – Reading the first two books with my six-year-old daughter recently (who loved the Disney film, which of course is mostly sweetness and light – and I like it, too, I have to admit), I have wondered if Mary isn’t some sort of deity in disguise. When animals, inanimate objects, and the powers of the natural world all sing and dance around you, what is one but a deity?

My daughter lost interest in the series halfway through the second book, but I loved them as a kid (albeit older than she is). I still think the books are far more interesting than the undeniably fun film.

“And Mary Poppins can be unexpectedly kind”

When kindness is unexpected, and is only an occasional bright-spot in the midst of “cruelty” and “borderline abuse”, it’s still part of the abuse pattern.

“She yells at Jane and Michael when they try to tell the truth” / “Mary Poppins’ stern rules and strict upbringing has brought magic to the children.”

There was a moment in the movie that brought these two points together, where the kids recount the magical adventures of the day to Marry Poppins, and she snaps at them and denies it. And… that always felt a bit gaslighty to me.

Yes, she’s scary, but magic should be scary and unsettling. “Do not meddle in the affairs of Nannies, for they are subtle and quick to anger.”

@9

Agreed. Mary Poppins is not nice because magic is not nice. It is alarming and scary.

Also, magic aside, as a child adults are weird and scary in many ways as the child learns to understand the signals to recognise that the kindly shopkeeper of yesterday is now in a filthy mood and is dismissive today. I think Travers catches that confusion very well.

I read the book after seeing the film as a child and liked it but it was the chapter about the twin babies losing the ability to talk to the birds that upset me (in a good way) and stayed with me. Re-reading the book recently, I was taken by how mystical the stories are.

For the record, I love the film.

@@@@@MikePoteet

Well, she does kind of remind me of the Old Testament God heh

@a1ay

“Do not meddle in the affairs of Nannies, for they are subtle and quick to anger.”

As a former nanny, you made me smile and yes, I was a traditional follow-the-rules, children need stability sort of nanny though not as

cantankerous as Mary Poppins.

@Del – While I don’t disagree with your assessment of the privileged minority, I should point out that the text is pretty clear that Robertson Ay spends most of his time sleeping and puts shoe blacking on hats and that sort of thing. Mr. Banks does have a job, and in the books – not in the movies – we do see Mrs. Banks doing a lot of housework: dusting, ordering food and carrying it home (which given the size of the household is no joke), and sewing. So they aren’t quite the idle rich, and Jane and Michael are expected to pitch in as well.

@Tekalynn – That does fit not just Mary Poppins, but several things said in the various magical trips taken by the children.

@DougL – There’s suggestions here and there in the text that Mary Poppins actually is a deity, especially in the later books, when her character was more set.

@percysowner and angiportus – And there you have two examples of just how polarizing the character of Mary Poppins can be :)

@Pam Adams – I realize Bert didn’t make enough money to take Mary out – but Mary Poppins seems surprised by the whole thing, which she never is in later adventures, and there’s no suggestion in that story that she’s the one who initiated the magic.

@MikePoteet – Yes, I think the second and third books, in particular, suggest that Mary Poppins is a deity of some kind. I don’t think it’s at all coincidental that all of her relatives just happen to be magical and that the cow turned to her mother for advice, or that she ends up doing things like helping to hang stars in the sky and that sort of stuff.

@cythraul – The gaslighting is far, far worse in the books, with Mary Poppins taking the children on even more adventures and then not just denying that the adventures happened, but threatening punishment if they continue to insist that they happen – and acting insulted. It’s at least emotionally abusive, although Jane and Michael do seem to survive.

@a1ay – That’s hilarious; thanks :)

@a-j – I had the same feeling about the Annabel chapter in the next book.

@gigi – Oooh, I look forward to your future comments here :)

The story with the twins losing their ability to talk to the birds, and the birds sadness over it is the one that sticks with me too. As a metaphor on aging and a loss of innocence, it feels ‘true’ to me. Plus, ever since then I’ve wondered what babies are thinking about.

Reading these books as I child, I was always ticked off at how MEAN Mary Poppins could be. But, I realized that her sourness kept the books from being to sweetsy. And, she certainly didn’t stop me from wishing to trade places with Jane and Michael.

“random stars that decide to do a bit of Christmas shopping”

They are not “random” stars, they are the Seven Sisters, AKA the Pleiades, of whom Maia is the eldest : Maia, Electra, Taygete, Alcyone, Celaeno, Sterope, and Merope.

I actually always found it strange that people think of Julie Andrews’ Mary Poppins as cuddly or cutesy. I only rewatched the film recently, and she is actually very firm, unbending, and decidely unsaccharine. She isn’t as nasty as the original Mary Poppins could be, but she similarly refuses to acknowledge the magic she is doing, and never gets too close to the children. I think people tend to remember “Spoonful of Sugar” and think of it as being typical of the entire performance, but it really isn’t. Mary Poppins is less sugary and more “Close your mouth, Michael. We are not a codfish.”

“You cowered before me; I was frightening. I have reordered time. I have turned the world upside down, and I have done it all for you! I am exhausted from living up to your expectations.”

Mary is an Istari sent over by Elbereth to search for Merlin. It’s about time for a certain shadow to reform and for Aulë to awaken the

Khazâd

Regarding the gaslighting accusations, my assumption is that Mary is trying to teach the children to keep their mouths shut so they don’t end up sectioned.

Great commentary.

I recently noticed how these stories sometimes contradict each other. In the first book, stars are friendly humanoid girls, foil cutouts glued to the sky, and faraway bits of magical light that make you need to dance if one falls on you. Yet it works!

I think book Mary Poppins and movie Mary Poppins are close kin. Movie Poppins doesn’t have as much time to snap at the kids as book Poppins, but she’s still not at all cuddly. In fact, Michael gives Book Poppins spontaneous hugs a few times, and I can’t really imagine doing that to Movie Poppins.

Also, supposedly one of the things Travers objected to was Movie Mary being pretty rather than plain like Book Poppins—but I just read 5 of the books & I don’t find anything suggesting Book Poppins is at all ugly. Dutch doll, black hair, turned up nose, pink cheeks–none of that says “plain” to me.

And, yes, she and Bert are absolutely dating. It may be the longest, most low-key dating relationship ever, but this is not purely platonic, not with her making sure to meet him *right after* arriving at Cherry Tree Lane, not to mention chalk-painting teas, gifts of elaborate (formerly chalk) bouquets from him to her, and the way he is *always* there to see her off.

The books did make me wonder why she wanted to spend so much time being a nanny–it’s not just caring for the children, she’s also doing the shopping *while* looking after Jane and MIchael and pushing the twins & later Annabel in a pram, getting things mended, and at one point taking over the kitchen when the cook needs to visit a sick relative. Seems an odd choice!