Pen has lost her parents. She’s lost her eye. But she has fought Kronen; she has won back her fragile friends and her beloved brother. Now Pen, Hex, Ash, Ez, and Venice are living in the pink house by the sea, getting by on hard work, companionship, and dreams. Until the day a foreboding ship appears in the harbor across from their home. As soon as the ship arrives, they all start having strange visions of destruction and violence. Trance-like, they head for the ship and their new battles begin.

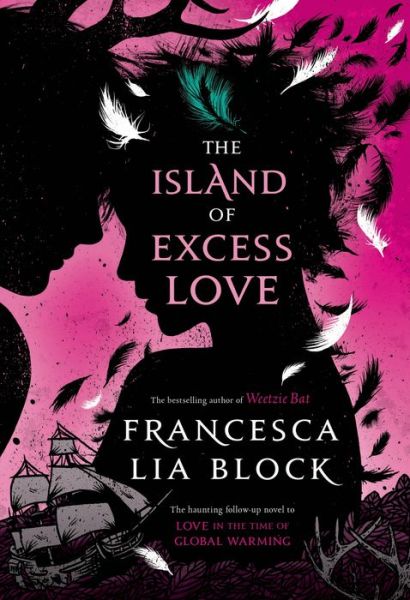

Francesca Lia Block’s The Island of Excess Love is available August 26th from Henry Holt & Co. This companion to Love in the Time of Global Warming follows Pen as she searches for love among the ruins, this time using Virgil’s epic Aeneid as her guide.

1

Conflagration

Now that I can no longer believe in God or gods or goddesses, I pray each night to my dead mother, Grace, that we will survive another day and be able to stay here in the pink house on the edge of the world, that my friends and my brother and I will be safe, the plants in our garden will continue to grow, and the water in our spring will not dry up. As far as the rest of the planet after the Earth Shaker? I don’t even know where to begin.…

My parents weren’t religious, but before each meal when Venice and I were little we would hold hands and say, “Thank you for the food, god and goddess,” our own tiny prayer. I guess all the myths my parents read us were a kind of religion. The myths and the images in the art books my mother collected. But there aren’t many books or paintings left now. My friends and I intend to make as many of our own as possible.

Ezra—or Ez, as we call him—is our resident painter. Today he is painting another portrait of Ash who poses draped in a sheet, his feet bare and firmly planted, his dreadlocks tied back, his eyes darkly seductive. The final painting, inspired by the symbolist painter Franz von Stuck, will depict Ash as an angel winged and playing a horn; I’ve seen the sketches. It’s appropriate to paint Ash with those broad gold wings because he told us that when the Earth Shaker hit, the wind blew him across the desert and landed him inside the body of the T-Rex statue in Cabazon where we found him. The horn in the painting will symbolize Ash’s musical powers; he once charmed a monster into submission with it.

Ez has superpowers of his own; during the Earth Shaker he was able to save himself from being crushed by a toppling bookcase.

And there’s the power of his art, which, in its realism and magic, seems almost as mysterious.

Ez took the wings from his imagination and memory but at least he has a real young man to paint, and one he adores at that. I’m not sure if there are any winged creatures in this world, let alone many other young men. In the days since Ez and Ash and Hex returned to me from the dead—or so it seemed—we haven’t seen anyone else. I’m relieved every day that no one has come looking for us, trying to harm us or steal our food, but relief turns to a cold hollow in my belly when I think that there may not be anyone out there to come. There may be Giants like Kutter, the one who spared my life when I told him the story of how he was cloned by his maker, Kronen. Or Kutter’s brother, Bull, whom I blinded with my only weapon at the time—a pair of scissors.

I’m more relieved about the fact that we haven’t seen more Giants than about anything else. There’s no way to explain what it feels like to be engulfed in those fleshy, greasy palms, to smell a Giant’s fetid breath or feel their blood splash against your skin. No Giants here, though, just us, as if we’re in some sort of protected zone they can’t penetrate. Because I think they’re out there somewhere. How else could this many humans and animals have vanished so quickly? The Earth Shaker didn’t kill that many on its own. I believe there are Giants savaging what’s left of the world.

Ash gazes into Ez’s eyes as Ez paints him; they could do this all day. Not that I blame them; I stare at Hex any chance I get. I just don’t paint well enough to capture him on canvas. So instead I tell myself this running story about him, everything he says and does. Like right now: he’s reading a musty copy of The Aeneid by Virgil in my father’s old armchair, the faint light of afternoon that has broken through the omnipresent clouds coming in the window. My beloved is dressed in his usual black clothes, his so-black-it-looks-blue hair slicked back from his face, showing off his widow’s peak and making his eyes look even bigger than they normally do. Hex’s skin is so pale and thin you can practically see through it and sometimes I wish I really could: look right at his heart. That heart, it saved my life, just by the fact of it surviving the end of the world and finding me.

“ ‘Excess of love, to what lengths you drive our human hearts!’” Hex reads aloud, as if he knows my thoughts. The Aeneid is the story of how the hero Aeneas founded Rome. When Hex discovered the book on my parents’ bookshelves he freaked out and made us all read it; he still shares passages with us throughout the day. “As you may recall, that’s when Aeneas betrays Queen Dido’s love and leaves her to go start a new civilization.” Sometimes Hex likes to play schoolteacher.

“‘Excess of love,’” I say. “What is that, even? How can there be an excess of love?” I want to go over and kiss his lips. They look as soft as they feel. I imagine his sharp teeth hiding under them.

“If it blinds you to the truth. If it paralyzes you and keeps you from taking action,” he says, without looking up from his book. I realize I’m jealous of an ancient Roman poet who died in 19 B.C. He was a man, too, so it shouldn’t bother me; Hex is definitely all about the girls. But his remark worries me.

Sometimes, especially after losing my left eye, I wonder if I’m blind to the truth but if so I don’t really care, as long as my illusion includes my loved ones.

I go over and sit at Hex’s feet, running my hands up the leg of his jeans to feel the warmth on my cool skin, feel the way his calf muscles bunch up. “Come help me make dinner,” I say.

“Virgil is my new favorite poet,” he says, not really hearing me.

I pout, making my mouth look, I hope, like Ez’s muse Ash’s full lips always do, even in repose. I thought Hex’s favorite poet was Homer, whose Odyssey seemed to parallel our lives to an uncanny extent. “Didn’t you reread The Aeneid again last week?”

“Yes, but now I’m reading it for inspiration.” Hex stops and looks up at me from under the arrow of his hairline. “I’m going to write an epic poem.” And then he adds, “For you,” and grins, making me forget that I was ever annoyed with him. Hex has a way of doing that. Maybe one advantage of being alone on the planet, or at least the continent, is that I don’t have to compete with any pretty girls for his attention. I’m his only muse, his only lover, and he’s all mine.

“Pen!”

My little brother, Venice, is shouting my name as he tromps in from the garden with our dog, Argos. I hear two boy-feet in worn-out sneakers and four prancing paws on the kitchen linoleum. “The pumpkin’s ready!”

If Ez, Ash, Hex, and I are busy with our stories and paintings, my brother has the most important work of all. He’s in charge of the food supply and it’s like his hands are charmed; he can coax fruits and vegetables from the slushy ground outside our home. If people once considered roses or diamonds the highest compliment, now we all feel that way about a cauliflower or an apple.

Venice’s pumpkin is small and round, a glossy orange color. At another time—we call it Then—we would have carved a face and put a candle inside. Children dressed as demons would have come to our door asking for candy. Now we pray every day that real demons don’t come and that there will be enough food to last us through the uncertainty ahead.

In the garden, the vines grow over the gazebo Hex and Venice built and the baby pumpkins hang like small lanterns, but we didn’t expect this one to ripen so fast. Of course, Venice’s garden isn’t like any other so it’s not that surprising. When I arrived back at this house after my journey I buried the hallowed bones of Tara, the sacred girl the Giants killed. Ever since, under Venice’s care, things seem to grow in our garden as if they are charmed.

If I were a plant, I’d be charmed by Ven: his dove-gray eyes and the way he coos like a dove, too, while he works, the way he tries to hide his smile by shifting his gaze and pressing his lips together.

He’s shot up in the last few months and he can outrun me when we venture out to race around the periphery of the house, but he’s still my little brother. He’s the one I always worried about before there was any real reason to worry and the one I thought I’d lost forever when the danger exceeded anything I could ever have imagined.

Venice, Argos, and I go into the kitchen where my mother used to cook for us. Those great dinners; I took them all for granted until she was gone, swept away by the storm that followed the Earth Shaker and then by the hand of one of Kronen’s Giants. The kitchen still reminds me of my mother so much—the blue and white tiles she hand painted with flowers and animals, the big wooden table where she served us breakfast, the window overlooking the garden. Missing her doesn’t feel like such a terrible thing anymore. It lets me know that her memory is still within me; she’s gone but she’s here, too. That’s one thing my journey taught me about loss. Or maybe I just have to believe this because otherwise I would have perished from grief by now.

My parents might be gone, the sea has encroached on most of the garden, and there’s no functional refrigerator or stove, but I still find the kitchen one of the most comforting parts of the house.

Venice sets the pumpkin on the counter and we admire its even striations and jaunty stem. My stomach is growling already. We might have an enchanted garden but food is still scarce these days. There are no animals to hunt even if we could bear the idea of killing one. The Giants have devoured them all. Every so often we even get secret deliveries of canned and bottled goods, candles and matches, and even clothes and shoes. We never see who leaves them in the night and I’ve never caught the person, though I’ve tried. I’m pretty sure it’s Merk, whom we consider our strange-angel guardian, otherwise known as my genetic father, the one who saved me from my enemy Kronen and his men three times, although not before Kronen had taken my eye.

I put my hand up to the patch I wear, reflexively, every time I think of how Kronen bobbed his head at me, pursing his lips, gleefully stroking that little beard; the way it felt to thrust my sword through Kronen’s jacket made of dried skin and into him, into a human body, when he tried to have me killed. Killing someone is the last thing I thought I’d ever do. But I never expected my life to be like this.

Here I am, unable to consider killing an animal but I actually killed a man, using just a sword. I used to be a girl who went to high school, stayed home on weekends studying the encyclopedia, art history, and mythology, whose greatest heartbreak was an unrequited crush on my best friend, Moira, and the possibility of losing our home to foreclosure when my father lost his job. Now I’m a oneeyed killer without a father or a mother or a world. My brother and my friends tell me that I’m a hero but I feel like that was all accidental and I hope it’s behind me. I’ve learned to accept my half vision and consider the loss of my eye and my innocence the price I had to pay for being able to return to my home, find Venice, and reunite with Hex, Ez, and Ash.

They come into the kitchen as if my thought conjured them.

“Pumpkin stew?” Ez says, rubbing his hands together. He’s our best chef. “I’ll roast the seeds for on top and even cook the onions in some olive oil tonight.” The oil appeared on the doorstep with the last mysterious delivery. “There’s kale for salad,” Venice adds, pulling a dark green head of ruffled leaves from his pocket, and even Hex smiles. My junk-food lover has really changed his ways; he hardly ever mentions cheeseburgers or diet soda anymore. It’s as if that life, Then, was a dream we had.

Or maybe this is the dream? As long as I have my boys with me I’ll take it; I’ll stay asleep.

After dinner and cleanup Hex leads us in our nightly group meditation where we sit in a circle breathing and trying to clear our minds.

Tonight Hex wants us to tell what we’re afraid of and when it’s my turn I say, “Having to leave here.”

“Me, too,” Ez echoes.

“Why?” asks Hex. He always wants to get to the root of our feelings.

“Because I don’t think I can take any more of the real world,” I admit.

“As long as we have each other you can.” It’s the first thing Venice has contributed to the discussion and makes me smile in spite of myself.

“And you’re stronger than you realize, Pen,” Ash adds and Ez nods and squeezes my hand.

But I don’t feel strong; I feel like a small, fragile Cyclops. Like a Cyclops, one-eyed, wrecked from battle. This Cyclops would rather go back to sleep than get up, face the world, and fight again. My expression must give that away.

“You’re a storyteller,” Ez reminds me. “That’s heroic.”

“How is that heroic?”

“Well, you make up some wicked cool words,” Ash teases. “Schnuzzle? Thrombing? Come on, that’s priceless.”

“And potentially life saving,” Ez contributes solemnly.

“Very funny.”

Venice’s gray eyes get that light-filled, dreamy look. “You have to imagine things before you can do them. Stories help us see.”

“The story is the seed, the action the flower,” Hex says.

“How do you define heroism?” I ask him.

“ ‘And though his heart was sick with anxiety, he wore a confident look and kept his troubles to himself.’ Virgil, speaking of the hero Aeneas who must emerge from his defeat in the Trojan War and sacrifice many things in order to found a new civilization.”

“‘Kept his troubles to himself.’” That pretty much describes Hex. “Which means you can’t tell us what you’re afraid of?”

“Bad hair?” Ash winks at Hex.

I pull on one of Ash’s faunish dreadlocks. “That’s you more than him.”

“Well first, ow. And second, I don’t want to go out there either.” He frowns through the window at the encroaching night. “No matter how strong Pen here is.”

“You’re all forgetting your strength,” Hex says, a slight snarl to his upper lip.

“You still didn’t answer Pen’s question,” Ez challenges. “Or maybe you’re not afraid of anything?”

Hex sits up straighter and glares at an invisible spot a few inches in front of his face. “ ‘Must you make game… with shapes of sheer illusion?’ ”

Ash flings his hair back over his shoulder. “Say what?”

“It’s a passage where Aeneas is talking to his mother, the goddess Venus, who helped the Trojans. She kept rescuing her son when Athena, the goddess on the side of the Greeks, tried to harm him, but Venus always came in disguise. To answer your question, I’m afraid of illusions.”

And the words crawl up my vertebrae to the nape of my neck.

Later we all say good night and head to bed. We are trying to conserve our candles for emergencies and so our days are determined by the rising and setting of the sun. I don’t mind because I have Hex to sleep with. He’s my personal flame.

We hold hands as we walk upstairs to my room, our fingers woven like threads making a quilt, a quilt that would tell a story of our battles, our separation, and our reunion. Argos always sleeps with his nose tucked into the curve of his body at the foot of Venice’s bed in the room next door to mine, and Ez and Ash have my parents’ old bedroom.

The floorboards creak under our feet, swollen with moisture that seems to have seeped into the entire house. I shiver with cold and with the anticipation of being held in my lover’s arms. When we reach the bed Hex faces me, takes my right hand, and holds it up to his chest so I can feel his heart, yes, thrombing under the tattoo that reads Heartless. Hex is the most heart-ful person I know but he likes to pretend he’s “badass,” as he would say. And he is that, too. He’s the one who taught me to sword fight, who fixed the leaking roof and scavenged for pieces of unbroken glass to replace the windows that were smashed in the maelstrom. Our pink two-story clapboard house might not be moisture proof but it’s pretty safe and solid compared with anything else I’ve seen out there—well, except for the Giant’s lairs but those don’t count.

“Feel that?” Hex says. “An excess of love, baby.” His pulse is so strong I can imagine the whole shape of his heart, as if I’m holding it in my cupped palm.

I put his hand to my heart, too. “No such thing.”

He lifts me up—even though we’re about the same height he’s always been stronger—and lays me on the bed. I shiver, cold until he eradicates the chill with the length of his warm body, his face buried against my collarbone so his hair tickles my chin. Outside I can hear the sea, our music mix. Sometimes I wonder what’s out there in that ocean, if any life is there, if a world still exists on other shores. Were the Earth Shaker, and the tsunami that followed, felt around the planet? Did other Giants decimate the population? I could wonder all night but now I just want to pray to my mother and listen to Hex’s heartbeat, just want us to remain in our secret place until we die.

“Why are you afraid of illusions?” I whisper to Hex as I taste the first intoxicating petal of the flower of sleep.

“Because I think we’re all going unconscious here in some way. And we can’t afford to. We have to be strong. You never know what’s coming.”

It’s almost enough to make me snap awake. But not quite.

I dream about my mother, Grace. She’s in my room with me—it’s so real. I can see her long hair and her white nightgown blowing in a salt-sea breeze that’s come through the window. Her eyes are the same bright gray as Venice’s eyes. There’s a coronet of gold and baroque pearls on her head and a white dove perched on her hand. She looks young and healthy, not the frail near-corpse I held in my arms just before we were separated for the last time. All this BS about being okay with the loss of her, as long as I have her memory, is gone. My heart is atrophying. Even in my sleep I feel tears dripping hot streaks down my face, taste their salt in my mouth. I reach for her, once, twice, three times, but each time she escapes me.

I know that my mother wants me to leave, go somewhere, but I don’t understand. She wants me to go to Paris? Athens? Rome? Venice! My mother loved that city the most, obviously; that’s why she named my brother after it. I remember our trip to Europe when I was ten. It didn’t seem like a real place to me at the time—the gondolas, the little canals running between the ancient, ornate buildings. Does Venice, Italy, even exist anymore? But that’s not what my mother means. No, something else. She wants me to go away from the house, to do something important. She shows me a tiny painting she’s made. It’s of a man with overlarge, palliative blue eyes, flared nostrils, full lips. And a crown of antlers on his head.

I ask her who he is and she says he’s the king and that I must go find him. I ask if she can go with me. It’s the only way I can do it, I say. She shakes her head, no, she can’t. I’ll have to do this by myself. The world is depending on you, she says.

What world?

The next day I wake with Hex spooning me. It’s so cozydozey here, and warm, why would I ever want to get up? But something propels me. In spite of the cold and the veil of sleep still clinging to my body, I go to the window. The sky is its usual gray, not even a few streaks of rose glimmering through the clouds, and the sea just outside our house is liquefied lead.

On its surface, moored against a rock I see a wooden ship, creaking softly—perhaps that is the sound that woke me. The large tattered sails flap in the wind. A coldness goes through me as if I’ve been immersed in the morning ocean and goose bumps blast up on my arms and shins.

Before I can wake Hex I hear the front door open and see a figure run out of the house toward the ship in the water. Venice.

“I’m coming!” he cries. He is stumbling and falling, getting up again and running with his arms outstretched. I race downstairs, through the kitchen, and out the back door.

“Venice! Stop! What is it?”

He doesn’t seem to hear me. As I catch up with him and touch his shoulder he turns and stares. I realize he is sleepwalking—that blank expression. Sleepwalking was something that terrified me as a child—lack of consciousness in motion, like the reanimated dead, the revenants who peopled those old black-and-white zombie films played on TV at witching hours. I say his name again.

“There’s something out there,” Venice whispers, his sea-gray eyes pooling bigger.

And then my little brother’s hair bursts into flame.

The Island of Excess Love © Francesca Lia Block, 2014