There is not a person alive that has not reacted with dread when one of their family members, usually a bit older and a bit drunker, says something like, “Did I ever tell you about the time I…” It is the inevitable prologue to the story you’ve heard over and over and over again, told with the same intonation and yielding the same punch line. Fairytales are our cultural equivalent of such never-ending stories. They are tales that keep coming up generation after generation on a sort of endless loop.

By some estimates there are over 300 renditions of Snow White alone, and that’s not counting Julia Roberts’ 2012 attempt at the role of evil queen in Mirror Mirror. So why is it that we keep returning, time and again, to these same old fairy stories? Recently the answer would appear to be that adults want to reclaim these stories from children. (I defy anyone to tell me that children were in anyone’s mind when they wrote the screenplays for Maleficient or Snow White and the Huntsman.) The real question is whether this impulse to make these traditionally G-rated stories more PG, or in some cases NC-17, is new or merely a reversion of the fairytale to its original, dark form.

Over the years many have observed that fairytales are not particularly suitable for an audience of children. In writing about his own “adult” fairytale, Stardust, Neil Gaiman wrote,

“Once upon a time, back when animals spoke and rivers sang and every quest was worth going on, back when dragons still roared and maidens were beautiful and an honest young man with a good heart and a great deal of luck could always wind up with a princess and half the kingdom—back then, fairytales were for adults.”

However, long before Mr. Gaiman the Brothers Grimm came under quite a bit of heat for some of the fairytales they included in their collection of Children’s Stories and Household Tales.

And rightfully so.

The Juniper Tree with the murdered child reborn as a bird singing, “My mother, she killed me, My father, he ate me, My sister Marlene, Gathered all my bones, Tied them in a silken scarf, Laid them beneath the juniper tree, Tweet, tweet, what a beautiful bird am I,” sounds like something that Wes Craven might have put into one of his movies. Yet, the Grimms defended themselves.

In the introduction to the second volume of their opus, you can almost hear the snarky—well snarky for 1814—tone with which they rebut the complaints they must have fielded when their nineteenth century readers came to some of the more lurid passages and had to explain uncomfortable things to their little Johns and Marys (the most popular baby names in 1814 and 1815 and seemingly through the entire 1800s for that matter).

In this context, it has been noted that this or that might prove embarrassing and would be unsuitable for children or offensive (such as the naming of certain situations and relations—there are those who do not even want them to hear bad things about the devil) and that parents might not want to put the book into the hands of their children.

Still, the book buying public wanted fairytales for their children. And so, in the name of commerce, fairytales have been ruthlessly cleansed of offending subject matter—typically defined as anything involving sex. One example of this “purification” process can be found in how the arc of the Grimm Brothers’ version of Rapunzel bent toward the puritanical over time. In the original telling, Rapunzel’s nightly rendezvous with her prince resulted in a not too surprising pregnancy.

“Frau Gothel, tell me why it is that my clothes are all too tight. They no longer fit me.”

By the end, the twin bundles of joy she was originally carrying have been written out of the story entirely and her virtue is intact.

“Frau Gothel, tell me why it is that you are more difficult to pull up than is the young prince, who will be arriving any moment now?”

By the time Andrew Lang, in the late 1800s, got around to anthologizing every tale he could lay his hands on in his epic twelve volume Fairy Books collection, he frankly admits that he has bowdlerized the stories with the little tykes in mind. However, in the introduction to The Green Fairy Book, he goes a step further, writing,

“These fairy tales are the oldest stories in the world, and as they were first made by men who were childlike for their own amusement, civilised adults may still be able to appreciate fairy tales but only if they can remember how they once were children.”

This idea, that fairytales have become children’s tales not because of selective editing, but because adults have “evolved” beyond them, is quite extraordinary. Are fairy tales an inherently “childlike” form of storytelling? If they are, that raises the obvious question of where the modern trend of “adult” fairytales comes from and what it means. Is it an indication that modern adults are devolving into a more child-like state? The Jackass movies certainly would seem to lend the idea some credence. However, the fairy stories (whether movie or book) that are being embraced by adult audiences are not simply repackaged fairytales in their original, or semi-original, “child-friendly” form, but rather are true “retellings” of fairytales.

It would be difficult to find anyone who would argue that Gregory Maguire’s versions of Cinderella or Snow White or The Wizard of Oz are ‘by the book,’ or for that matter meant for an audience of children, though admittedly there are some catchy tunes in the musical version of Wicked. Likewise, Marissa Meyer’s Lunar Chronicles take fairytales into space, while Danielle Page in her series Dorothy Must Die posits the quite reasonable question, why would Dorothy ever willingly choose to go from Oz back to dustbowl era Kansas. And Katherine Harbour in her new book, Thorn Jack, takes on Tam Lin, a folk ballad that in its second verse lets you know that this is not your everyday children’s fare:

O I forbid you, maidens all,

That wear gold in your hair,

To come or go by Carterhaugh,

For young Tam Lin is there.There’s none that goes by Carterhaugh

But they leave him a token,

Either their rings, or green mantles,

Or else their maidenhead.

Even if we can agree that modern retellings of fairytales are not your grandfather’s fairytales, it still raises the question of why? Why, with all the storytelling possibilities available, do authors keep returning to fairytales? In her introduction to The Annotated Brother’s Grimm, Maria Tatar writes that fairytales, “true” fairytales, have a “discrete, salutary flatness.” The scholar Max Lüthi explains this concept of flatness by describing the fairytale world as,

An abstract world, full of discrete, interchangeable people, objects, and incidents, all of which are isolated and are nevertheless interconnected, in a kind of web or network of two–dimensional meaning. Everything in the tales appears to happen entirely by chance—and this has the strange effect of making it appear that nothing happened by chance, that everything is fated.

In other words, a fairytale in its truest form is a story that needs no explanation, will tolerate no method, and eschews any kind of logic, except perhaps its own. It is a narrative dreamland in which anything is possible, and in which the why’s and when’s and where’s are left to the imagination of the reader. And, perhaps it is these very gaps in narrative that are drawing authors and audiences alike back to fairytales today. The very incompleteness of the stories can serve as a vivid backdrop for staging new stories, for exploring characters from new angles, and for prodding into the cracks and holes to run down those why’s and when’s and where’s.

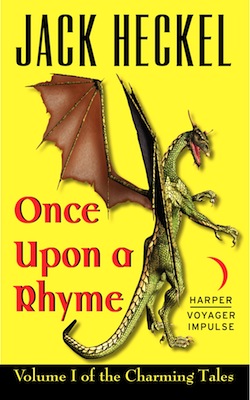

opens in a new window An example of a gap or empty spot in fairytale narrative that is near and dear to my heart, and that I write about in my soon to be released book, is the question of the male protagonist, the “Prince Charming” character. Who is this fellow? Does he ride about rescuing damsels all the time or is that just a side-job? And, what would a fellow be like if he was the most dashing, handsome, desirable man in all the world, and everyone knew it? Imagine if you were Brad Pitt (I know I do all the time), but that there was no one to compete with, no George Clooney, no Ryan Reynolds, no Taylor Lautner, or whoever else has chiseled abs and perfect hair these days.

An example of a gap or empty spot in fairytale narrative that is near and dear to my heart, and that I write about in my soon to be released book, is the question of the male protagonist, the “Prince Charming” character. Who is this fellow? Does he ride about rescuing damsels all the time or is that just a side-job? And, what would a fellow be like if he was the most dashing, handsome, desirable man in all the world, and everyone knew it? Imagine if you were Brad Pitt (I know I do all the time), but that there was no one to compete with, no George Clooney, no Ryan Reynolds, no Taylor Lautner, or whoever else has chiseled abs and perfect hair these days.

The possibilities seem endless, and ultimately that is what I think draws readers and writers back to fairytales happily ever after after happily ever after, because in the end the fairytale traditions are enduring foundations of storytelling. The idea that magical things can happen to ordinary people, that people can fall in love at first sight, and that a story can be compelling even when you know from the beginning that it occurred once upon a time and ends “happily ever after.” And if these new retellings of you favorite fairytales still leave you wanting more, if there are still gaps in the narrative, remember the author is only being true to the art form, and of course, leaving open the possibility of a sequel or two.

Jack Heckel is the writing team of John Peck, an IP attorney living in Long Beach, CA who is looking forward to the upcoming release of Once Upon A Rhyme, and Harry Heckel, a roleplaying game designer and fantasy author, who is looking forward to the publication of Happily Never After.