Jerry Beche should be dead. Instead, he’s rescued from a desolate Earth where he was the last man alive. He’s then trained for the toughest conditions imaginable and placed with a crack team of specialists on an isolated island. Every one of them is a survivor, as each withstood the violent ending of their own alternate Earth. And their new specialism? To retrieve weapons and data in missions to other apocalyptic versions of our world.

But what is ‘the Authority,’ the shadowy organization that rescued Beche and his fellow survivors? How does it access timelines to find other Earths? And why does it need these instruments of death?

As Jerry struggles to obey his new masters, he begins to distrust his new companions. A strange bunch, their motivations are less than clear, and accidents start plaguing their missions. Jerry suspects the Authority is feeding them lies, and team members are spying on him. As a dangerous situation spirals into catastrophe, is there anybody he can trust?

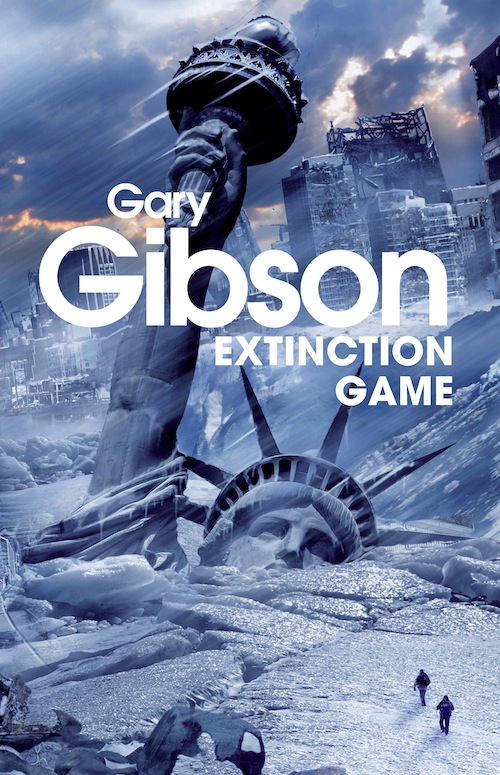

opens in a new window![]() Below, check out a preview from Gary Gibson’s riveting, action-packed post-apocalyptic survival story, Extinction Game—available September 11th from Tor UK!

Below, check out a preview from Gary Gibson’s riveting, action-packed post-apocalyptic survival story, Extinction Game—available September 11th from Tor UK!

ONE

There’s an old story I once read that starts like this: The last man on Earth sat alone in a room. There was a knock on the door. Except for me it wasn’t a knock, just some muddy tracks in a field that told me I was not, as I had long since come to believe, the last living human being.

But before I found those tracks and my world changed in ways I couldn’t even have begun to imagine, I stood in front of a mirror and wondered whether or not this would be the day I finally blew my brains out.

The weapon of choice was a Wesson semi-automatic I had prised from the fingers of a man named Herschel Nussbaum ten years before. This was just moments after I killed him and four days after he had nearly tortured me to death. I kept the gun in a bathroom drawer, under the basin before which I now stood. Its barrel was sleek and grey, and the grip had wooden insets of a fine, dark grain that felt warm against the skin when you picked it up. I thought about opening the drawer, how easy it would be, how quick. Click, bam, and no more Jerry Beche. No more last man on Earth. Just an empty house, and the wind and the trees, and the animals that had inherited the deserted cities and towns.

I’d had this same thought almost every morning for the last couple of years. Under any other circumstances this would, I admit, appear excessively morbid. But I was all alone on a world devoid of human life. I feared growing too old or too sick or so feeble I would no longer be able to make that choice, to end my life on my own terms. The only certainty I had left was that one day I would take that gun out of its drawer and join the rest of my species in extinction. I’d push the barrel against the roof of my mouth, angled up so the bullet would blow straight through the top of my skull. I had nightmares, you see, about screwing it up. I dreamed of blowing half my face off and waking up in a pool of blood and bone fragments, still alive.

Or at least, that’s what I told myself I’d do.

I didn’t open the drawer. Instead, I picked up a jerrycan of water placed by the door, and poured some of it into the sink. I splashed a little on my cheeks, and when I looked up I caught a glimpse of my unshaven face in the mirror over the sink. I looked thin – gaunt, really. It had been a long winter, and I wondered, not for the first time, if some undiagnosed masochistic streak kept me from settling down somewhere warmer than England. For the first time I noticed a touch of grey at my temples that made me look like my father.

It makes you look distinguished, I imagined Alice saying.

‘It makes you look distinguished,’ she said from behind me.

I turned to see her leaning against the frame of the bathroom door, arms folded across her chest, one corner of her mouth turned up in amusement. She wore a thick navy cardigan over a red T-shirt that clashed violently with the ratty green scarf knotted around her neck. I never saw her wear anything else.

‘Remember you have to check the wind turbines today,’ she said, stepping back from the door. ‘Last thing we need is another power failure.’

I nodded mutely. There had been another outage the previous evening, the lights fading to a dull brown before eventually stuttering back to life. I had a diesel generator as backup, but fuel was precious and I didn’t want to use any more than was absolutely essential. I had made repairs to the transmission lines only the week before. The problem, then, could only lie with the wind turbines up the hill that were still functioning.

I dried my face and stepped back out into the corridor, then hesitated. I could hear Alice humming from the direction of the kitchen. What was it that suddenly felt so wrong? What was it that… ?

Of course. How could I have forgotten?

I made my way back to the bedroom and picked up the broken I Ching coin from the bedside table, a piece of black cord tied around it so that I could wear it around my neck. It was my lucky charm, my talisman, the last remaining link to the life I had lost long ago.

When I entered the kitchen, Alice was gone and the house was silent. I breakfasted on wheat grain milled by my own hand, softened with powdered milk and filtrated water. This was flavoured with a dribble of honey from the food stores I maintained in the cellar. I heated some water on the wood-burning stove and washed the meal down with freeze-dried coffee, then made for the hallway. I pulled on a heavy jacket and picked up my shotgun, my breath frosting in the cold air.

The past few weeks had been bitterly cold, sleet and snow tumbling endlessly from grey English skies, but over the last few days the temperature had started to crawl back up. I stepped outside, seeing the snow had begun to melt. In the distance, past the trees lining the road, I heard crows call out to each other, their voices stark and flat in the monochrome landscape. The wind turbines were visible at the peak of the hill a quarter of a mile away. Altogether a peaceful winter morning.

In the next moment, the crows exploded upwards from a small copse of poplar farther up the hill. I tensed, wondering what had spooked them. There was a real danger of encountering predators with no memory, and therefore no fear, of human beings. Over the years I had caught glimpses of bears and even lions, presumably escaped from zoos or circuses after their owners died. Several winters ago I’d had a nasty encounter with a polar bear that came charging out of an alleyway.

Dogs were undoubtedly the worst. The smaller ones had mostly died out in the years following the apocalypse, leaving the larger, fiercer specimens to dominate. After a winter like this one they would be hungry indeed, and I never stepped outside my door without a loaded shotgun under my arm.

I listened, but heard nothing more. More than likely the crows had been startled by a badger or fox. Even so, I kept watching out as I shut the door behind me. I walked past an outbuilding containing a processing tank that turned cheap vegetable oil raided from deserted supermarkets into biodiesel, then I stepped through a wooden gate leading into a field where sheep had once grazed. The place in which I now made my home was an ultra-modern affair, a boxy construction with broad glass windows, constructed, so far as I could tell, mere months before the apocalypse. I had it found it pristine and unlived in; better still, it was easy to keep warm, even in the depths of a winter such as this.

I followed a well-worn path up the side of the hill until I came to a line of twin-bladed wind turbines. There were a dozen in all, tall and graceful and rising high above me. Only three still functioned. The rest stood silent, despite my vain attempts to repair them. I had never been able to find the necessary spare parts.

The turbines were one of the main reasons I chose to settle where I did. I had driven fence posts into the hillside, paralleling the path leading to the turbines, and strung thick cables all the way down the hill to my chosen home. From the top of the hill I could see what had been the town of Wembury in the distance, still Christmas-card pretty under its blanket of snow despite the recent rain.

The blades of the remaining three turbines that still worked spun steadily under a freezing wind. I made my way inside a transformer shed next to one of them and first checked the voltmeter and then the storage batteries. I kept expecting to come up the hill and find another of the turbines dead.

‘I keep expecting to come up the hill and find another of the turbines dead,’ said Alice. I could just see the other half of the Chinese coin I wore around my own neck peeking out through her scarf, on its silver chain. ‘I’m amazed they’ve lasted this long.’

I pulled a fuse box open and took a look inside. ‘Always the pessimist,’ I said.

‘Takes one to know one.’

I glanced over at her, still wearing her blue cardigan and green scarf. She’ll catch her death dressed like that, I thought, then quickly pushed the thought away.

I could see a streak of rust at the back of the fuse box, at the top. I looked up to the roof of the shed, to where I had cut a hole for the power cables. The weatherproofing had partly come away, letting in rain and snow; one more thing I had to fix. I pulled out the fuse nearest the rust stain and saw where it had become touched with corrosion.

No wonder the power had nearly gone the other night. I pulled a spare out of a box on the floor and replaced it.

‘Job done,’ I said, stepping back, but Alice had vanished once more. I went out of the shed, but there was no sign of her. It was maddening sometimes, the way she’d come and go.

I glanced down at the broad muddy patch that spanned the distance between the nearest turbine and the transformer shed and saw several sets of bootprints. I stared at them, then blinked hard, sure I was seeing things, but they were still there when I looked again. They were fresh: their outlines clear, the grooves in the mud filled with a thin layer of water, indicating they had been made some time within the last couple of hours. I stared at them numbly. It had been a couple of days since I’d last been out, and it had rained heavily. I peered more closely at them, seeing they were quite different from my own bootprints. Then I looked around, trying to make sense of it, the blood thundering in my ears.

‘Alice?’ I called out, the words choked. ‘Have you… ?’

I stopped mid-sentence. Of course it hadn’t been her bootprints, couldn’t be. I looked again; there were three distinct sets of prints. They had stood here, walking back and forth across the mud, studying the turbines, the shed and presumably the cables leading down to the house.

Three people. Three living, breathing human beings.

That’s when it really hit me. My heart began to thud so hard it hurt. I fell to my knees, tears rolling down my face. I wasn’t alone.

But then something else occurred to me. If I wasn’t alone… who, exactly, had come calling?

Extinction Game © Gary Gibson, 2014