I love Spenser’s The Faerie Queen. I love it with a geeky, earnest passion for its bleeding trees, its book-vomiting serpents, its undefeatable shield-maiden and her rescue of a woman named Love.

That said, I always read it with double vision—one eye always redacting, reading Duessa and the Saracen Knights against their ergot-laden grain. Of course the first really interesting female character we meet is a duplicitous evil-doer; of course being friends with the Queen of Night and getting her to spirit your boyfriend away before some (quite literal) kill-joy murders him means you’re a villain instead of a resourceful badass. It was strange, reading a book and loving it enough to spontaneously compose explanatory fanfic for its ugly parts, but that was most of my undergraduate English degree.

When I saw the title of Saladin Ahmed’s “Without Faith, Without Law, Without Joy,” I straightened up out of a slouch. I felt my eyes brighten with hope. He’s going to do it, I thought. He’s going to write my fanfic.

He didn’t, quite—he did something rather different, sharper and crueller and more crucial. In “Without Faith, Without Law, Without Joy,” Ahmed takes an ugly allegory, literalizes it into secondary-world fantasy, and in so doing deftly makes a new allegory for the treatment of Muslims in Western society.

This week on Full Disclosure: if you do a Google Image Search for “Saladin Ahmed,” my face comes up; however, in spite of us both having Scary Arab Names, we are in fact different people. Also, only one of us is Muslim.

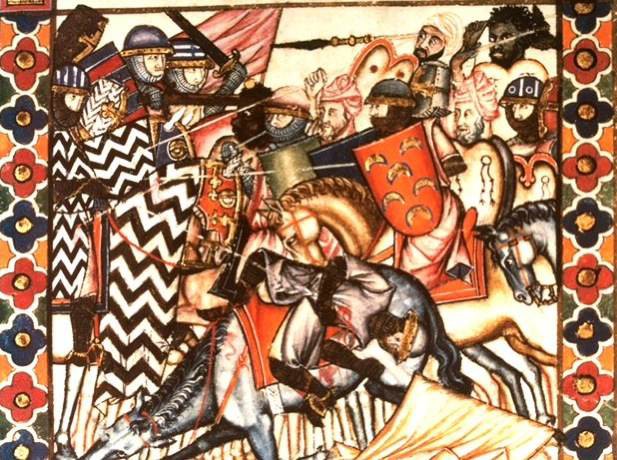

“Without Faith, Without Law, Without Joy” has a straightforward structure: using quotes from the Faerie Queene as a frame, it takes up and subverts each of the incidents involving the three evil Saracen brothers—Sans foy, Sans loy, Sans joy—who beleaguer Una and the virtuous Redcrosse Knight in Book I. Translating their names to Faithless, Lawless, and Joyless, Ahmed imagines that it is Redcrosse himself who is a wicked sorcerer, having stolen three brothers from their lives in Damascus and stripped them of their names and memories in order to make them enact a lurid pantomime for Redcrosse’s benefit and spiritual advancement.

We were sipping tea in a room with green carpets, and I was laughing at a jest that…that someone was making. Who? The face, the voice, the name have been stolen from me. All I know is that my brothers and I suddenly found ourselves in this twisted place, each aware of the others’ fates, but unable to find one another. Unable to find any escape.

Now my eldest brother has been slain. And my next eldest brother has disappeared.

Who am I? I do not know how he changed our names. But in this world of lions and giants and the blinding shine of armor, I am called Joyless, as if it were a name.

It was not my name. It is not my name. But this is his place, and it follows his commands.

I am a child of immigrants who fled war. The loss of names, language, and connection to cultural memory and heritage through those things is something to which I am especially vulnerable. It was difficult not to read this story as specifically about immigration: about the enormous, inscrutable forces of war and geopolitics that force people from their lands, homes, and families, then makes the price of their entry into another country the shedding of everything that still connects them to those things. In the face of such pressures, to remember and keep one’s name is an act of resistance—and it is what the so-called Joyless struggles towards in the story.

But the story’s an allegory for more than that. The ambition of “Without Faith, Without Law, Without Joy” makes me want to perform the most sincere of slow claps. It isn’t just about politics as wicked magic—it’s about the faces the Other is made to wear for the comfort and pleasure of those who are allowed to see themselves as heroes in a story. In the original text, being non-Christian is all it takes for a person to be Faithless, Lawless, and Joyless; the work this story takes upon itself is to show how rooted are Faith, Law, and Joy in Islam and Arabic family culture. I needed this story in a big way, and it moved me deeply.

While I found myself wishing at times for richer prose, I’m happy to chalk that up to my own palate; I think Ahmed’s plain-spoken prose with occasional gut-punches of beauty is an appropriate tool for the work this story is doing. It’s also perhaps unfair that I longed for something the story doesn’t provide (and functions serviceably without): an alternate reading of my beloved Duessa.

If you’ve read The Faerie Queene (or the first book, anyway), you’ll recall that Duessa succeeds in spiriting Sans joy away in a black cloud before Redcrosse can kill him, and along with the Queen of Night persuades none other than famed Son of Apollo Aesculapius to heal his wounds. This was the note I was hoping the text would end on – perhaps a revelation of Joyless’ daughter as the one who rescues him once he has remembered himself, able to represent the Muslim Woman always represented as duplicitous because she wears a veil, whose modesty is made fetish, who is constantly sexualised through Western perversions of the concept of “harem.” I was hoping she would appear with her own triumphant subversion, a daughter instead of a lover, fierce and intelligent and able to save her father because he recognized her when her uncles couldn’t.

But there I go with fanfic again. I do feel it was a missed opportunity—but I appreciate this story keenly all the same. It gave my Saracens histories, their own true names, and leaves one of them on the cusp of rescue—from where I can allow my own imagination to spirit him away to safety.

I’m very grateful for that.

Amal El-Mohtar is the author of The Honey Month, a collection of stories and poems written to the taste of 28 different kinds of honey. She has twice received the Rhysling award for best short poem, and her short story “The Green Book” was nominated for a Nebula award. Her work has most recently appeared in Lightspeed magazine’s special “Women Destroy Science Fiction” issue, Kaleidoscope: Diverse YA Science Fiction and Fantasy, and is forthcoming in Uncanny. She also edits Goblin Fruit, an online quarterly dedicated to fantastical poetry. Follow her on Twitter.