In a culture where ritualized torture is used to teach its people strength through long-suffering, a foreign sufferer unintentionally teaches them something stronger . . . something gentler.

This novelette was acquired and edited for Tor.com by senior editor Claire Eddy.

The thin tip of the branding iron glowed a mellow orange, two gentle swoops intersecting near the top. I knew the symbol, just as I knew why it was being used. It was the Mal numeral three, and marked the number of cycles I’d been enduring Talenfoier—a very old word interpreted by modern linguists to mean torture of the captive. But I’d studied its Mal lingual root, so I knew better. Refinement through pain was its truer meaning. My skin would be written on to mark the duration of my suffering and tolerance to the seven cruciations of Talenfoier.

“Be still, Sheason,” the refiner said.

“I’ve outlasted your knives. I think I’ve earned the right to hear my name when you place your first brand.” I showed a weak smile. “I’m Vendanj.”

The Mal man gave me the same impassive look he’d worn these hundred days while plying my flesh with his razor-thin cutters. Leaning close, he rested the heel of his palm on my chest to steady his hand. He then gracefully rotated the finely-tipped brand with his fingers. The smell of hot iron wafted up around my face.

“Jaimen,” he replied, speaking his own name for the first time in our many torturous sessions together. He was a member of the Aerin Loh, those trained to deliver Talenfoier. “Now set yourself. Hot iron unnerves a man in a way knives never do.”

He meant for me to take firm hold of the rods set into the armrests of the chair in which I sat. The rods reminded me of warping pegs on a loom. Pegs used by rugmakers to maintain thread tension. The reminder had proven useful. I’d learned from my grandfather that the key to a strong weave was moderate thread tension. Too tight and the rug would possess no give. Too loose and it wouldn’t knit together well. Forcing my body to relax under the artful application of blades parting my skin had helped me endure the first cruciation worthily.

I’d only flinched once, and that had resulted from a rare mistake by my refiner, his blade cutting into muscle when he’d only meant to part the skin. As to worthily, I knew this because I was receiving my first brand, marking the end of knifework, and signaling a hundred days of slow, deliberate hot-iron branding to come.

But it wasn’t just the weaver’s lesson that helped me relax as this first brand neared my flesh. Three cycles of Talenfoier knives carefully opening my skin had left me bone-tired. Exhausted mentally and emotionally, too. Which was, after all, its real purpose. The immediate pain of Talenfoier was a bridge to the real breakage: that of spirit. Only a broken spirit leads to refinement. Or so the Mal believed.

Still . . . a brand.

My muscles were tightening reflexively even before I gripped the rods. I forced myself to relax, like a viola string tuned down a pitch. I’d found that doing so also made these sessions pass more quickly. Not because my refiner worked any faster. Relaxing into the pain just seemed to change my perception of time. And a man lives by his perceptions, dangerous as they can be. So I let my body sink back into the chair, my hands wrapped loosely around the pegs. I held myself steady, but not rigid.

Jaimen waited patiently for me to prepare myself. I let out a deep breath, then nodded. As his sharp eyes focused on my chest, I fixed my own attention near the neckline of his shirt. Brands rose from his chest in a careful column, twisting up the side of his neck and cheek.

Before coming into the lands of Mal Valut, I’d seen others with such chronologies burned into their skin. Not many, but a few. And only a few because even modern linguists were generally accurate in one way about Talenfoier: Its intent, if you weren’t Mal, was death—the ultimate refinement, went the old jest. Since coming into Mal Valut, I’d seen a thousand branded necks. Every natural-born Mal seemed to have a column of numerals seared into their skin, each column unique. Some were short, some reached high on the face. And the symbols themselves varied in subtle ways. Talenfoier’s meanings, I realized, were several.

During my first cruciation, I’d learned that a short stack of numbers was known as a brief counting. That’s what was expected of me, since I hadn’t been taught Valutara, the Mal technique for enduring Talenfoier’s pains. I’d studied the concentration methods of many paths—the Chae of the Nallan advance brigades, the Soma known of the Wynstout nomads, and even the Pliny Tu taught by Dimnian temple nuns. Most of them involved separating the mind from the body.

Valutara was different. When the pain began, you went inside it. You inhabited it completely. Embraced it as readily as another man reclines in the shade at the end of a day’s labor.

But I wasn’t Mal. I hadn’t spent a lifetime preparing for Talenfoier, as they did. And the cruciations weren’t practiced outside the Mal lands.

So I’d had to rely on my Sheason skills to survive, rendering the energy of the Will in subtle, healing ways after each knife session. But now I would become familiar with the feel of a brand. I wasn’t sure if the techniques I’d developed would work as well with the second cruciation.

And if I meant to win the honor I’d need to walk free, to complete my real purpose in coming here, my chest and neck and face would have to read like Jaimen’s. Like a long calendar.

The brand finally touched my skin—a small, focused fire.

It wasn’t the first time I’d smelled the sour stench of my own charred flesh. But those memories were far away and blurred now beneath the pain blooming across my chest.

The sound of searing skin ended before Jaimen pulled his brand away. The burning went on, though, deepening into my body with each passing moment. Jaimen’s eyes locked on my own, assessing the effects. Enduring Talenfoier was only the first part, and not the most important. Enduring well was the thing. I was already weak, and this pushed me to my limit. It felt like I’d been shoved toward some kind of edge. An edge inside me. My grip on who I was.

Each of the past hundred days I’d waited until they’d returned me to my little room to invoke the Will and heal the lacerations on my back. Lacerations made by careful, successively deeper cuts to the same patterns, reopening tissue that had just started to mend. Jaimen was reaching for a fresh brand. He’d place it precisely where he’d placed the first, to deepen the burn. The thought of it overwhelmed me.

Today, I couldn’t wait.

Without any outward sign, I called a portion of my Will, quietly rendered healing inside my body. Beneath the skin, the damaged tissue mended. It was a tricky bit of rendering, like diverting irrigation water from its regular path to a suddenly dry field. There’s only so much of the necessary element. A delicate balance had to be maintained to avoid compromising one for the sake of the other. I took great care not to damage part of my body while healing another.

More difficult still was sustaining the effort. Like a Lieholan singer whose Song of Suffering lasts a full seven hours, I maintained a constant invigoration of the flesh beneath the brand, as Jaimen continued to work.

A Sheason doesn’t usually self-heal. It’s not advisable. Still, the careful art of it was one I’d become rather good at. The reasons for that have their own stories. Stories of battle. Even other stories of torture.

But the memories of my other tortures didn’t help me here. Being branded hurt like all the glories of hell, so-called. The burn didn’t sink inside me, though. I wouldn’t allow it. The pain of the brand took hold in my skin, but that was all.

After the seventh iron had been pulled away, Jaimen’s eyes narrowed with slight suspicion. After a long moment, he nodded with satisfaction, and said matter-of-factly, in his thick Mal accent, “Next, branding.”

The brand I’d just received was just the mark of completing my first cruciation. Jaimen was reminding me that the next three months would be a cruciation of hot iron.

He then left me alone as he’d always done, to rest a few moments before I’d be escorted back to my room.

I let go of the pegs, unwinding my tension like a weaver loosening his loom. The angry scar on my chest had risen, white, forming the numeral I knew, with some appended serifs I did not. Around it, patches of red and black. I fought the urge to accelerate healing in the skin, too. I’d need all my strength for tomorrow’s session, when the branding would begin in earnest. Over the next hundred days, a new pattern would be burned into my skin. I didn’t know where, or what that mark would signify. But it would likely be broader, hurt more.

Silent gods, burned. Over and over. In the same place. Every day.

And while I didn’t know what sigil they’d scar me with, the repetition itself was symbolic, reflecting the challenge to meet day after day beneath a hard sun. A succession of Mal suns. The routine of it maddening. Because while Talenfoier described these focused sessions of torture, it also represented—for the Mal—a way of living. Their routine was Talenfoier. Their routine was constant pain as an ever-present reminder of mortality. Their routine made them stoic, hard. Exceptional at war, which seemed just another routine to them.

For me . . . my routine was about to change.

I arrived back at my small room, supported by one of the refiner helpmates I’d come to call gray men. I’d never heard one speak, or even make non-verbal sounds in their throats. They wore shapeless clothing of an indistinct gray color, and walked with constant attention on where and how they placed their next step. This gray man saw me to my bed, then left in a prompt but unhurried fashion.

When my eyes adjusted to the dimness, I found myself staring at a young woman lying across from me on my room’s second bed. She looked all of eighteen, if I was any judge of age. At the foot of her bed sat a small trunk and a pair of shoes. The Aerin Loh had assigned me a roommate. I was dizzy still, so I didn’t fully trust my eyes, but the girl’s face looked like it had been taken to with a pair of brass hands. As had much of the rest of her naked, trembling body.

I wanted to go to her. Wrap a wool blanket around her thin shoulders. But I was too weak even to do that.

When the hours of night had grown small, I awoke to the sound of her near-silent sobs.

I said nothing, lying still for quite a long time. I took in the shape of her, the wounds I could make out through the shadows. And knowing what it would mean for me the next morning, I rendered a portion of myself and added some strength to her form. Just enough to dull the aches of blood bruises, mend ripped skin, and true up a jutting bone. And that much left me entirely depleted.

The woman drew a deep, sleepful breath, returning our room to the peace of the small hours. I soon followed her to dreams.

The still, mild air of summer morning had settled in around me. I sat just beyond the rear door of the small house where I passed my nights in Darles Hem. Hem was a Mal city nestled in amidst a long run of hillocks. It was unremarkable save, maybe, the excellence of its refiners at Talenfoier. But it had good mornings. Great mornings.

The air had a dry quality to it. Not desert-like, but not humid. I neither burned nor perspired in the heat. Ground dew was enough to freshen the smell of shrubs and leaves, without leaving them damp. And hill aspen rose everywhere, some spreading their branches above me. Aspen leaves were the gods’ way of laughing—their flutter in even a mild breeze like the sound of a smile. Sunlight streamed through those leaves, their shadows dancing across my legs.

I could smell parsley growing in moist earth nearby. And mint. They were clean smells that made the morning that much more pleasant. I’d slept fitfully, even after assisting the girl, pain flaring in my skin each time I rolled or stretched. So, now I dozed in the calm of this rear garden. Civil, I thought. This feels civil. Even if the moment was fleeting.

I closed my eyes and smiled. My prison here wasn’t piss-covered stone and rusting chains and dirty straw to wipe my ass. I’d known such places. Here, my prison was weariness. Day in, day out: Talenfoier. I had strength enough to endure each hour, and little more. No guard stood at my door. No bed checks or restraints. When my strength permitted, I was even allowed to walk the city. But the pain of cruciation and the weariness that followed were constant fetters.

All I had to distract myself were these soft morning moments. They restored me more than anything else. There was even a small hare that foraged a patch of cabbage laid in near the rear fence. I’d come to think of it as a pet. I called him “Amen.” I took no small pleasure watching Amen move about, all twitchy-nosed.

This morning, Amen was working at a snip of parsley when footsteps sent him scurrying down a hole. I opened my eyes, and saw first a set of bare feet. Looking up, my roommate came into view. She sat in a chair a few paces away, her legs likewise bare. Beside her chair, she laid a pair of ankle-high shoes she’d been carrying. She’d draped a loose shirt around her shoulders, but nothing more. Her breasts cast half-moon shadows across her ribs.

We sat, unspeaking, for several long moments. Finally, she broke the silence, her voice husky as from overuse. “Why are you here?”

I pulled up my own loose shirt to expose my first brand.

She shook her head. “Why have you come here?”

I gave a weak smile. The only kind I felt capable of. “I’m Vendanj. And I’m sorry, but what’s your name?”

“Yes, rude of me. Seelia,” she answered.

“Well, Seelia, are you interested for yourself, or for someone else?” I then pointed to her exposed breasts. “No brand. You’ve not started your Talenfoier.” I wondered if she’d prove to be a cell-mate confidante, the kind meant to garner trust by shared misery, extract information for a jailor. It was a clumsy device.

Her return smile pulled at the cracks in her lips. She winced a bit. “Talenfoier starts at birth.”

“For a Mal, you mean.”

“For living things,” she replied, no hint of sarcasm.

I pointed at several yellow-and-purple bruises across her face, legs, arms, chest, and neck. “Then your beating wasn’t random.”

“Is any beating random?” She licked her lips to moisten the torn parts.

I smiled a bit more broadly then. “I’m a bit obtuse this morning, I suppose.” I looked back to see if Amen had ventured out of his hole. “What I mean is, since you’re here, I assume you allowed yourself to be beaten.”

She gave me a sharp look, one that softened a touch after a moment. “Some call it the cruciation before the cruciation. It makes one teachable.”

“Being beaten,” I said, careful to keep judgment out of my voice.

She shook her head, her eyes becoming distant as she stared into a patch of sunlit soil. “It’s any of a hundred things. And for a woman, it starts in earnest when she gets her blood.”

I was suddenly reminded of the painters of Masson Dimn. The art schools there taught mastery over brush and oils. Canvas paintings as tall as bristlecone pines were created and shipped to the manors of those who could afford to pay. But no image ever left a Dimnian painter’s care before it was deliberately marred in some obvious way. The imperfection, they taught, kept them from arrogating to the stature of the abandoning gods—Noble Ones, they called them.

The Noble Ones had framed the world, the old stories said. One of these gods had gone mad, ruined balance. Once they believed the world beyond repair, they’d abandoned it. So the story went. Dimnian artists purposely marred their art, considering it a visual prayer of deference to those gods. Others, who’d ceased to believe there’d ever been Noble Ones, viewed the imperfection as the right way of humility.

And like a piece of Dimnian art, it seemed, each Mal was kept in a constant state of imperfection, enfeeblement. Pain to remind them, refine them. But of what? For what?

“I saw your back,” the young woman said without any real tenderness. “It’s unusual to start with the cruciation of knives. Someone wanted you to give in quickly. Or die of bleeding. Your kind has thin blood. Runs fast.”

“Sorry to have been a disappointment.” I managed a low chuckle at my own joke. “The brands will come next.”

She had that faraway look again in her eyes. “The Aerin Loh find the right sequence for each of us. But for most the sequence is the same.”

“Most Mal, you mean.”

This time she nodded. “With you, it’s not . . . what’s your word . . . refinement?”

I nodded. I knew what she’d say next.

“With you it’s a way to die.” She shifted to face me directly. “You haven’t answered my question.”

I stared back, hearing for the first time the yellow-billed swallows in the aspen above me. Theirs was a late-morning song, sung softly, as if for themselves and not to declare territory or attract mates. I remained silent, listening to the trill-yawt-yawt-yawt-soooooon, made over and over. I had no intention of talking during those first notes of song.

In the lull between bird calls, I said, “You have something that doesn’t belong to you. Your war-leaders covet its qualities. But they’ve no idea how to use it. It belongs to me. To my kind.”

“The ingot of steel,” she said. “Some call it the ThousandFold.”

I nodded. “I’ll gladly leave when it’s been returned.”

“That’s not likely.” She paused a long moment, her eyes bright with consideration. “You must have known that. Why wouldn’t the Sheason come and seize it by force?”

I laughed, and immediately regretted it, the simple act pulling at my wounds. “Contrary to what you may have heard, we don’t prefer war. But I also knew that simply asking would do no good.”

“So you chose the cruciations as a way to prove yourself.” She shook her head, whether in respect or at the foolishness of it I couldn’t decide.

“Perhaps I can earn Mal trust. Then they’ll listen to me when I tell them why they cannot . . . should not wield the steel they’ve taken.” I gave her a grave look, coming to the crux of it. “And I’m going to need that ingot of steel soon. To answer larger threats than the Mal have from their neighbors to the south.”

“You’re saying your wars, your concerns, are greater than ours.” The first look of real judgment rose in her eyes.

I stared back. “I’m saying that your people took something that doesn’t belong to them. Something they hope to use to fight a small war. They won’t discover the key to that steel. And while they search, its larger uses slip away.”

“Then go and tell them that,” she offered, incredulous.

I smiled at the innocence. “They know why I’m here. But they’ve no reason to believe what I say is true. I could be telling lies to get what I want. No,” I said, feeling suddenly more weary, “I need the weight of cruciation if I’m to be heard. And failing that . . . there’s always war to take it back.”

She regarded me a long time, her eyes more thoughtful. That’s when the girl’s beauty finally struck me, a beauty of earnestness, and of eyes that saw more than she allowed herself to say. Her straight blonde hair hung loose and long, a grace upon her skin, and a sharp contrast to the dark bruises from her recent beating. More than these things, I liked the movement of her mouth when she spoke. Men notice such things, though it’s not something they talk about. But there was a universe of compassion and sensuality in it. She gave words life and appeal, forming subtle suggestions that went beyond the words themselves. The more beautiful part was that she had no idea she was doing it.

After my mention of war, and our long staring, she didn’t call me a fool. She didn’t laugh or smile or sigh. She didn’t leave me to my ruminations, or go back inside to entertain her own thoughts. She simply said, “Will you join me for a walk?” Which wasn’t so odd, I suppose, until she bent forward and carefully positioned the shoes she’d brought with her. Before she slipped her feet inside them, I caught a dull gleam in the shadows of each. Short spikes, maybe half a finger’s-width high, poked up from each instep.

I watched as she carefully eased her toes past the spikes, gingerly lowered her heels, and stood.

We walked the streets of Darles Hem in companionable silence. I never saw Seelia wince or shudder, though the edges of her shoes grew wet with blood. There might have been a momentary grimace when she first put her full weight on the instep bores, but I could have imagined that. Of late, I’d grown rather sympathetic to the pain of others.

For an hour we strolled. She never took a cautious step. And to people she knew, she smiled and made warm welcomes.

When we were alone enough that I wouldn’t be overheard, I commented, “I assume what matters is bearing it well.”

She flicked a hand dismissively. “Only in the most superficial sense. Yes, it’s shameful to draw attention to one’s own suffering. But the pain—”

“Isn’t who you are,” I finished, believing I’d begun to grasp the underpinning of Talenfoier.

“Wrong,” she said forcefully. “It is who you are. Part of you, anyway. That’s the problem with the thinking east of the Divide. You’re quick to remove a sliver.”

I’d heard this saying a time or two. The Divide was a great range of mountains that separated the Mal lands from the rest of the east. There were peoples in the Divide range itself. My people, the Sheason. But Seelia was lumping my order in with the rest of the Eastlands. I kept the smile off my face as I recalled another adage, one from the other side of the mountains: You’re callous as a heel west of the Divide. Thinking of Seelia’s instep bores, I wondered if I’d just happened on a bit of etymology.

She stopped, taking hold of my elbow to swing me around to face her. “It’s what’s wrong with Sheason rendering the Will to alleviate pain. It’s like . . . it’s like denying part of yourself. It’s arrogant.”

I stared back, confused, but also wanting to understand.

She sighed, and opened her mouth to speak. But she promptly shut it and led me onward with a bit more purpose in her step, which must have hurt a good goddamn. We followed a number of narrowing cobblestone alleys. I’m sure the uneven paving angered the wounds growing in her soles.

Down a quiet byway, we came to an unremarkable door, behind which I heard a weak sound. It was like hearing the plaintive cries of a goat separated from the herd across a wide valley. Seelia gave me a last look, then led me in to an interior room where the mewling grew a shade louder. But only a shade. Whatever was making this cry was weak.

Seelia greeted a nursemaid who sat quietly in a rocking chair, holding a child . . . the source of the sound I’d been hearing. When the woman stood, she gently transferred the babe to Seelia’s arms and withdrew. Seelia motioned for me to sit in the rocker the nursemaid had occupied. I sat, easing my skin against the backrest.

Without any somberness, she carefully placed the child in my arms. Not more than a month old, the babe was light. Too light. And its voice had grown hoarse, from crying, I assumed.

I began to have an idea about why we’d come to this dim room with its sheer drape over a small window. Why I was sitting in a shallow-arc rocker holding a sick child. My thoughts must have been obvious in my face, as Seelia quickly corrected me.

“You aren’t allowed to do anything but hold the child,” she said, not unkindly. “Leave the rest to Talenfoier.”

I heard many meanings in her words. And I realized I didn’t understand Talenfoier as well as I’d thought I did. Maybe not at all.

“Why are we—”

Seelia held up a finger, calling for patience. With her eyes locked on mine, she stepped backward and eased herself into a small chair. The seat might have been better suited to a child’s schoolroom. It left me with unsettling thoughts about who else might come to sit in this dire nursery. And why?

She let out a long breath. Not a sigh exactly. Nothing as loud or exasperated as that. She must have been glad to rest her tortured soles. But her face had never shown any signs of pain. She looked as peacefully indifferent as she had most of the morning.

I finally turned my attention to the child in my arms. She hadn’t ceased to cry. But cry is too big a word for the moan she was making. In its weakness, it seemed more a plea than anger or discomfort or hunger. I hadn’t much experience with newborns, but it didn’t take great genius to know that this little one was sick and sobbing for help. The sound of it was like the dry husks of standing corn, abandoned in a field, brushing together when stirred by a lazy wind.

A crust of grit and tears had hardened in her lashes, making it difficult for her to open her eyes. The movements of her limbs, once maybe vigorous in her complaints, were feeble now, slow.

I did the only few things I could think to do. I cleaned the child’s eyes. Blindness, I’d learned long ago, was frightening. Well, maybe not blindness, exactly. More not being allowed to see. Such darkness caused panic at the very least. Then I began to rock, gently. And with my own tired voice made my best effort to sing a lullaby. I hummed more than sang, since the words to lullabies were mostly lost to me. I might have been ignoring Seelia’s instruction not to do more than hold the child, but she didn’t try to stop my little song.

The child didn’t cease to cry. Not until her strength simply gave out. She dozed briefly.

Seelia sat watching. She didn’t shift or fidget. She didn’t comment. It wasn’t until the sun no longer shone directly on the sheer drape that she spoke, her voice thin as a whisper.

“It’s arrogant to try and avoid the pain that finds you. As if you don’t deserve it.”

I spared a look at the child. “What has she deserved?”

Seelia let a long moment pass. “One in twenty is born with blood disease. There’s nothing we can do. Except wait with them until they return to the earth.”

“You seem rather apathetic about it,” I observed.

“Other than sitting to watch a child die, you mean,” she returned with a hint of sharpness. I caught a glimpse of Talenfoier in her response. Only a glimpse. But in that moment I grasped new understanding.

“This is one of the cruciations.”

“Be more clear,” she said, her voice sounding like instruction.

I stared at Seelia. It could have been a trick of the light, but her eyes seemed to have the shine of tears.

“Not a cruciation for the child. Not whatever illness she’s suffering,” I said. “But that we watch her suffer.” I felt my own emotions in my throat. “And are helpless.”

Seelia sat forward, resting her elbows on her knees, which surely put more pressure on her soles. “Physical pain is nothing. You must learn to inhabit it, so that you can understand the pains that matter. Until you do, you’re like that babe. Your little hurts won’t teach you anything.”

“Are you helpless?” I pressed. “Is this child beyond your medicine?”

“Now you’re both arrogant and offensive.” Seelia’s eyes had grown dangerous.

But by that point, I was beyond caring if I offended her, or any Mal for that matter. To mock her—or more precisely to mock Talenfoier—I adopted the tone of a reassuring mother cooing to her babe. “You understand why I ask, I’m sure. Since your ways of refinement could be considered murder of a child.”

Seelia’s face fell utterly expressionless. It was the most disquieting look I’d seen from her yet. My mind showed me an image of her wearing that expression through the worst pain either of us could imagine.

“You will fail beneath the Aerin Loh brands.” She began shaking her head in disapproval. “Not because you won’t suffer through them. You have your rendering skills to block pain or heal wounds or whatever evasion it affords you. So your skin will carry the marks of accomplishment. But you won’t have gained Talenfoier, and the ingot of steel you came for will remain here.”

I showed her a defiant smile. “I may be an arrogant and offensive Sheason. But you, all of you, are so blessedly selfish, I’d . . .”

It wasn’t worth finishing that thought, because Seelia and I were both right. Such arguments—where there’s no fault—are a waste of good anger. Besides which, I’d decided to use my energy to live up to her dim appraisal of me.

Returning my attention to the child, I whispered low enough that Seelia couldn’t hear, “Not today, little one. Not you. Not today.” And though it would leave me no Will to self-mend when tomorrow’s cruciation of brands began their work on my flesh, I chose to render what energy I had on behalf of the child.

Quietly, I let my mind expand to gather in a sense of my own current vitality. The process, Weighs of Resonance, took just half a moment’s time. But in that instant, I knew the shape and cost of my own life’s breath. I knew how much of it I possessed—after so many sessions in Jaimen’s chair—and how much I could afford to give.

Still holding the babe, I moved my left hand to cradle her head. The feel of downy hair and soft skin on my rough fingers lent a kind of confirmation to my choice. It had to do with the unspoken expectation little ones should rightly have of the rest of us. It stirred me. Made me feel bold.

I began a soft, hum-like recitation. Strictly speaking, it wasn’t necessary. But I wanted the child to hear the sound of the words that described what I meant to do. She wouldn’t remember them, of course. But her heart would know them. Years from now she’d recognize their sound, were she to hear them again.

Seelia leaned forward. Not to intervene, but to hear.

If she was listening closely, what she heard wasn’t the sound of words attacking imperfections in the child’s blood. The simplest mistake a Sheason can make is to try and correct a problem, reverse or undo something. Effective rendering is done by simply declaring the desired state of a thing.

A man who’s been unfaithful to his wife grows bitter and weary trying to repent and amend his infidelity, rather than simply living forward, living faithfully. That’s the problem with religions like Reconciliation.

A woman can spend a lifetime trying not to repeat mistakes she feels her parents made, rather than simply being the kind of mother her own child needs. That’s the problem of blame.

Leaders spend years drafting laws to dictate what people may not do and the penalties that follow criminal behavior, rather than publishing what manner of citizen we should aspire to be. That’s the problem of government.

So I didn’t focus on what ailment tainted this child’s blood. Instead, I focused on the idea of clean blood. I formed a perfect image of a strong heart and veins coursing with life. A moment later, my body slackened in the shallow rocker, weaker by half.

But the silence that followed, as the child ceased her hoarse mewling, would be a sound I’d remember a good long while.

Much later, still sitting in the peace of that silence, Seelia whispered, “I told you not to intervene.”

I looked at her and offered a weary smile. “I notice you didn’t try to stop me. Thanks for being my accomplice in this crime.”

Seelia’s face was beautiful when she returned my smile.

Mother of gods did the hot iron hurt. And the stench of burnt flesh was constant. But the sessions passed more quickly than those with the knives. And before most Mal had taken their midday meal, I was back on my narrow bed, sweating freely. The ironwork (so called by my refiner) caused a daily fever in me.

Eventually, the searing pain ebbed enough that I could sleep. A carafe of room-temperature water and a supper tray of plain wheat bread and dry cheese were always waiting for me when I awoke. I ate them in my garden, where I sat with my shirt off, letting the cool shade ease the pain of the brands on my stomach and down the sides of my torso.

Seelia was always gone by the time I’d been brought back to our small room. But she’d return before evening shadows began to gather, and I’d be well enough that we’d walk. Our own shadows fell ahead of us, long and shapeless, since we usually strolled eastward. And not always to drab nurseries. I became rather well acquainted with what I could only think to call leper cloisters. Diseases of the flesh brought together these unfortunates, all of whom bore their ailments in the name of Talenfoier.

We also visited hospices in alleys where the rain never seemed to wash the dust from ivy that covered the walls. It left a smell like things forgotten. In these places I found a few wounded men and women returned home from battle, trying to convalesce—unsuccessfully, from what I could see. The extent of daily curatives available to them was clean water and cloth. I did notice a few needle-and-gut trays.

The hospices also cared for the extremely old, and for those with a myriad of non-infectious ailments. But care would be too strong a word for the attention the ill received in these places. I began to believe that these hospices’ main purpose was herding together those who were losing their private battles of personal refinement.

I’ll admit that to be a cynical view. But it was the best I could do. I was in a state of constant pain, battling my own Talenfoier. And likewise losing.

One evening, sometime in the middle of my second cruciation, Seelia and I ambled through a sparse night market. The sweet smells of honeycombs and sugarcane stalks drifted on the air. While I wouldn’t have called the atmosphere exactly festive, it was more cheerful than Darles Hem by day. And here, of all places, in what I’d come to think of as the convalescent quarter. I’d later learn how wrongheaded that thinking was. All of Darles Hem, all of the Mal lands, had ivy-walled byways. This was merely a borough. Seelia’s borough, as it happened.

But despite the pleasant surroundings, I felt heavy, bone-weary. And as Seelia and I made our way through the streets, I faltered and fell to one knee. She made no immediate move to help me up. I knelt there, feeling afire, the fever particularly strong that night. Beads of sweat ran down my neck and chest. I watched a few of them plunk down on the cobblestones beneath my bowed head.

Passersby in the street paid me no mind. I sensed they were aware of me, but no one tried to help. No one stopped or gawked or jeered, either. But then, I didn’t need their chastisement, I was doing a royal quality job of that myself.

Because kneeling there in the east quarter of Darles Hem, I caught sight of one of my failings. I may have mastered the Mal lingual root, and known a meaning or two for Talenfoier. But I had no idea how to live them. The ones that mattered, anyway. The ones that could help me . . . to endure.

I’d been walking with Seelia for almost fifty days now, lending what small support I could to beggars, children, and those too proud to ask. I’d been rendering a portion of my will, every day, to defy Talenfoier. To heal a few broken bodies or minds, and then bear the physical torments of my own morning sessions with Jaimen without the aid of my Sheason arts. And all I was doing was confirming the ugly understanding people outside the Mal lands held of Talenfoier. I must have looked a pity to those passersby who viewed me where I’d fallen in the street.

After a long while, Seelia bent and hooked my arm around her neck. We struggled to stand, making me wonder if she still had instep bores in her shoes. Then we limped together to a small side alley, where I slumped against the cool, rough wall. And sat.

She hunkered down in front of me. “Do you imagine you’re ready to understand now?”

I managed an ironic smile. “I look that broken, do I?”

She shared neither my mirth nor my self-pity. And she made no reply. Her face held the patient look of one waiting for a proper answer.

I stopped feeling any irony in the situation. I stopped smiling. I stared ahead at her. And I finally nodded, feeling teachable in a way I couldn’t remember feeling before.

“Without employing your Sheason skills to help yourself, and without understanding Talenfoier, you should be dead by now.” Seelia surveyed my brands briefly. “You’re too stubborn to die.” She paused and quietly added, “That’s about to end.”

I shook my head, not understanding.

“The next cruciation won’t bend to your obstinance. You’ll either have to stop helping these alley residents and start mending yourself . . .”

“Or what?” I urged gently.

Her expression was a portrait of reluctance. I could see her weighing the consequences of some choice, like maybe betraying a confidence. After several moments, she sighed and said in a mildly scolding tone, “Or, like I’ve been telling you for weeks now: You’ll have to learn Talenfoier. Really learn it. You can’t hold yourself separate and above it.” She slowed. “Or you’ll fail.”

“Fail to retrieve the ingot of steel your people hold hostage, you mean. I can’t imagine you really care about that.”

“That’s a dishonest reply. You know that’s not what I meant.” Somehow the lack of judgment in her voice was more condemning than her accusation.

“You’re dangling a carrot you know I can’t reach. You’ve lived a lifetime preparing for Talenfoier.” I stopped, trying to clarify what I understood about this path they followed. “You’ve been living Talenfoier all along, preparing for your cruciations. I don’t think it’s honest of you to suggest I could learn enough in a few short days. Hell, months even. I won’t achieve Talenfoier—”

“You don’t achieve it. It’s not an end state. You know better than that.” Her reproving eyes softened. “Talenfoier is a way of being. And I can teach you.” I was afraid I was never going to understand Talenfoier. A pregnant silence stretched as we stared at each other. The kind of silence that usually ended with unfortunate conclusions. Like mine now.

My voice sounded beaten when I said, “I’ll tend to myself.”

“Another dishonest reply.” Seelia’s tone held clear disappointment.

I shook my head, thinking about the ingot I’d come here to retrieve. “You’re right. That’s not what I’ll do. Even if I have to leave here without the ThousandFold steel.”

“It’s not dishonest because you wouldn’t do it,” she explained. “It’s dishonest because if you did, you’d be playing yourself false.” A nurturing smile softened her face further. “You don’t want to stop helping the few you can. And . . . I don’t want you to.”

I chuckled. “So you want to help me so we can keep taking our walks, is that it? What about the arrogance of robbing them of the chance to suffer?”

There was an answer to that in her eyes. I could see it. But she kept it to herself the way a parent might to preserve a child’s belief in things he was too young to know the truth about. Like the eventual death of a pet. Or the life the child imagines he will have. It’s cruel to dispel some beliefs, and makes a parent seem a betrayer in the telling. Seelia kept her secrets.

She took a long breath, fixed me with a solemn look. “When the pain begins, don’t resist it. Feel it.”

“How are those not the same?” I asked, quite genuinely.

“One is conscious. The other is not.” She knit her fingers together, settling in to a teacher’s posture. “Some choose to envision it like a dialogue between themselves and their pain. Become acquainted. Don’t try to evade it. Don’t try to think past it. Don’t imagine not feeling it now or in the future. Don’t wish for it to stop.”

To my confused expression she gave a lop-sided grin.

But I was trying to understand. “The anatomy schools in Estem Salo taught me that pain is an autonomic response. Meant to drive self-preservation. Our reflexive reactions are right . . . aren’t they?”

“Instinct, you mean. Yes, usually it’s fine to give it its head. Let it run.” She held a finger against her temple. “But Talenfoier is mastery over instinct.” Seelia stopped, correcting herself. “It’s allowing the proper instincts to dictate action and behavior.”

“So, how—”

“Start with your senses,” she said. “If you must, work through them methodically, one by one. Catalog the sensation of your pain with each faculty: sight, sound, smell, taste, and so on.”

“It’s a diversion,” I concluded. “You’re abstracting the pain by analyzing it—”

“No,” she said sharply. “Quite the opposite. You can’t know a thing without understanding its full shape, in all its particulars. The senses are remedial, I’ll grant you. But they’re easy for you to understand. They help you give the pain definition, intimate acquaintance.”

“And once I’ve cataloged it through all my senses?”

She gave me an appraising look. “Let’s not walk before we can crawl, shall we?” she said, showing me another patient smile.

The technique worked well enough that Seelia and I continued our evening strolls through the rest of my second cruciation. She seemed pleased, and I was pleased that she seemed pleased. But I kept that sentiment off my face. She’d have noticed and called me arrogant again.

I looked forward to our walks together, but worked hard to not let them become a way to think past the pain. That would have been an evasion of Talenfoier. I can’t say I was always successful. But I suppose being aware of that risk at all meant I was on the right path.

By the time I reached the end of my second cruciation, a beautiful pattern graced the skin of my torso and sides. In its fullness, I could appreciate the art of it. I suspected there were meanings in the shapes, too. But if so, they were impenetrable to me.

I sat in my garden, waiting for Seelia. I had so many questions that night. Questions about the column of cruciation brands that would run up my chest and neck and cheek, if I survived that long. Questions about the other forms of cruciation. Questions . . . about Seelia, that I felt maybe I’d earned the right to ask.

But she never showed. Even arriving a few minutes late would have been uncharacteristic of her. After waiting an hour, I knew something was wrong. I got moving, taking familiar routes to try and find her.

I stood out in Darles Hem like a broadleaf tree set among a stand of evergreens. For the most part, though, the Mal still took no note of me. I’d learned that their avoidance wasn’t disdain, really, just another side of their practical nature: Why take any interest in a Sheason undergoing Talenfoier? He’d be dead soon.

There were some exceptions to Mal indifference toward me. Not many, but some. They came once or twice an evening now. Usually from those I’d helped in some small way—treating an injury, or perhaps the injury of a friend or child. This acknowledgement came with a meeting of the eyes. No smile. No nod. And not ever a handshake or word of greeting. Just a shared look, without contempt or dismissiveness.

So on my more urgent walk that evening, I would likely never have found Seelia, had it not been for a subtle look from an elderly woman whose husband I’d cared for in his last hours. In the deep end of the Convalescent Quarter, with the sweet tang of molasses-covered apples and stewed peaches in the air, the old woman caught my eye. Twice, her gaze shifted from me to a set of doors set back from the road by a broad stone step.

I moved quickly to the doors, each of which bore an engraving I couldn’t decipher. But the wide front of this building, the broad step, the dual doors . . . it was a ceremonial place. I’d call it a temple, if the Mal held any reverence for the abandoning gods.

Knocking would be pointless. Without Seelia’s company, no one would admit me. So I quietly admitted myself. Soft candlelight illuminated dark interior hallways. And there was a silence within. Not an absence of sound. But an observed silence. That’s the only way I can think to describe it. It had a feeling to it. A feeling I’d become more than familiar with: the held-breath expectation of some infliction.

Dread knotted deep in my gut, because I knew Seelia was here.

I rose onto the balls of my feet and moved through the dim corridors as quickly and quietly as I could. I slipped past paintings depicting unspeakable acts, but depicting them with such care and solemnity that they seemed less atrocious by half.

I soon realized the front of this particular building was deceptive. Its interior was deep, and stairwells led up and down at regular intervals along the hallways. Inset shelving beside each door housed books and the occasional bust. I got the impression that the volumes and sculptures were somehow related to the discussions that took place behind those doors. Soon enough, it became clear this was a place of learning. But not arithmetic or letters or anatomy. My bet was that this was cruciation learning, Talenfoier training—as near a religion as the Mal had.

Winding deeper inside, I heard murmuring on the air, soft voices. I slowed, moving more cautiously, and followed the sound. Weaving my way forward, I discovered an interior atrium. Hanging oil lamps and stands bearing candles with multiple wicks brightly lit the small courtyard. Some of the candles stood beneath broad, shallow bowls. The smoke that rose from these bowls smelled of pine pitch. And around the inner sanctum stood a dozen figures, men and women, old and young. They wore the expressions of judges.

At the center knelt Seelia, not in an attitude of appeal, but submission.

“. . . because you’ve shared with the Sheason the First Modes of Valutara. Otherwise he would be dead. And his claim to the old steel would be done.”

The woman speaking was in her middle years. And her words came with little inflection. Brands in her skin reached up her neck to the base of her jaw.

Tell them, Seelia. Tell them you did it in exchange for my help with the helpless.

As soon as I thought it, I knew why Seelia would never do so. If she did, whatever judgment she was preparing to suffer would be extended to those who’d received my aid. And if I knew anything about my roommate after so many evening walks together, I knew betrayal was not in her.

But something wasn’t right. This judge knew that without some understanding of Valutara, I would be dead. Which meant she must know I hadn’t been calling the Will to mend my own body. Did this judge also know how I had been using my Sheason skills?

A dull ache started in my chest. That sensation of being on the verge of an unwanted understanding. Not like learning that the woman you love has been lying with another man. But that she loves that man. Not betrayal, but loss.

Seelia made no defense. And she never explained to her accusers anything of our time together. Not while I stood listening, anyway. I had no idea how long she’d been there, or what she’d said before I arrived.

The woman who’d last spoken nodded and stepped back, seeming to take Seelia’s silence for confession. A second woman, this one dressed in the close-fitted attire Mal soldiers wore to battle, came forward. She pulled out a short knife and took hold of Seelia’s queue of hair with her other hand. In a graceful motion, she cut away the braid. Then, she went to work on the remainder. With ungentle speed, she used that same knife flatwise to shave Seelia’s head. The scraping sound reverberated around the small atrium.

A knife does not a good razor make. Even an exceptionally sharp one. The pull across Seelia’s scalp was brutal. It left me with the impression of a sheep being shorn in wool season. Even from where I stood in the shadows, I could see the angry red scrapes across Seelia’s scalp, drawn by the rough shearing.

The tears in my friend’s eyes, though, didn’t strike me as tears of pain, but of shame. She never yelped or whimpered. And soon enough, she knelt alone again, her own hair a ring around her on the stone atrium floor.

Then a third woman, wearing gloves, lifted one of the brass pitch bowls and came forward with the steaming dish. From her pocket she drew out what looked like a paintbrush. Without hesitation, she dipped the brush into the bowl, and began applying hot pitch to Seelia’s scalp.

I expected a scream. I expected her to thrash and finally fight back. I expected others to rush forward to hold her in place. None of that happened. Only her face betrayed the pain she must have been feeling, a mask of agony. And even then for just a moment or two.. Then her face relaxed. She had deepened into Valutara.

The woman with the pitch didn’t stop with Seelia’s scalp. She painted my friend’s face, too, leaving clear her eyes, nose, mouth, and ears. After that, she moved on to her shoulders, her back, and finally her breasts.

Seelia soon slumped to her side, convulsing. Those around the atrium silently withdrew. It had all happened so fast. I stood in shock. But that’s not why I hadn’t intervened. I could have. I had energy enough to have dealt with those who’d savaged her.

I hadn’t interceded because I knew she wouldn’t have wanted me to. That was the hardest part of it: knowing I could have helped, believing she was wrong to submit, and still respecting her choice enough to watch her suffer. Perhaps I’d learned something of Talenfoier, after all. In more cities than I could count, I’d raised a rendering hand careless of the law or customs of those places. I observed one razor-simple sanctity: I defended those who couldn’t do so for themselves. I’d not found a time when this felt immoral. Though it had set me at odds with the rest of my order. I respected my Randeur, our Sheason leader. I respected every Sheason, come to that. But I’d stopped waiting for them to wake up to changes that might threaten the east. It was why I’d come for the ingot of steel the Mal unrightfully possessed. But in this moment I’d held my defiance in check. For Seelia.

When the atrium had been clear a full minute, I rushed to her side. Her eyes widened at the sight of me.

“You saw. Pitch of pine,” she said, her lips trembling.

Looking into her eyes, I understood. Her punishment could have come any of a hundred ways. The way they’d chosen said much about her offense. Covered with scalding pitch, a simple everyday element, applied quickly, with a brush. It was base. And the scars would be a mark of shame on her. Some that others would see. Some that would mar the delicate skin she showed only those she chose to take to her bed.

She hung in my arms like an overlarge doll. “Will you be all right?”

“Because I’m female?” I heard the tease in her weak voice. “There you go. Arrogant again.”

“Not because you’re female.” I looked over the hot pitch still clinging to her skin. “Because you’re a friend.”

“Who told you this?” She tried a smile, but it seemed to cause pain in her burned cheeks, and she let it go.

“They did this because you started teaching me Valutara. To manage my own pain.” It was suddenly harder to look at her ruined skin, knowing I was responsible. I cast my gaze about the atrium, pretending to watch for others who might discover me there.

“Look at me,” Seelia said. Her voice came like iron, cool and hard.

I did as she asked, and found her eyes glassy with tears. “Assumptions make you weak. Not you, in particular. All your kind. You use them like facts. It’s more of the arrogance that leads you down wrong paths.”

“You’re really going to lecture me right now?” I said, mildly incredulous. “You’re going to start a comparison of cultures, while you lie burning beneath a cake of pine tar?”

She grew quiet in voice and body, and in the look she cast me. I felt that feeling again, the one that tenses on the air before a hurt comes.

“I didn’t teach you the footings of Valutara to save you from cruciation.” She swallowed, the act slow and clearly painful. “I did it so you could preserve your energy to help those we walked each evening to find.”

I shook my head at the obviousness of her admission, and felt relieved. I’d braced to hear something more wounding.

“You’re not understanding me.” She took a long breath, and I could see her own consummate ability with Valutara. Her body relaxed beneath my arms as she embraced the pain more fully.

“Talenfoier is many things. It is knives through flesh. Hot tar on skin. It is suffering in order to end self-deception and your own mistaken paths.” She took another breath, pausing a long moment before saying, “And its sufferings are meant as partings.”

“Partings?”

She nodded, shame touching her face again. This time, though, it didn’t seem to be the shame of her chastisement.

“A wound of the flesh parts you from your arrogance. From the self-deception that you are separate from your pain. That you can or should avoid it.” She paused again, her eyes warm and searching. “It parts you from your own abilities. Teaches you humility. Teaches you of your dependence on others.”

I tried to shush her. “We can speak of these things later. You’re hurt—”

“But these are partings that follow from wounds of the flesh. They’re cruciations of skin and bone.” Her words sounded as though she spoke of childhood lessons. “Talenfoier,” she said with sudden seriousness, “teaches partings of other kinds. Partings that remove the illusion of unqualified loyalty and trust. These cruciations scar the heart. They work at the soul’s tender needs. To harden you. Make you ready for battle. For life.”

That imminent-hurt feeling thickened in the air again.

Seelia nodded, as if feeling it herself. “Your branding tomorrow will not be one, but two,” she said. “One for your second cruciation . . . and another for me.”

I stared down at her, reeling with understanding.

“I’m so sorry, Vendanj.” One of her tears stole down over the pitch now hardening on her cheek. “I was placed in your room to play on your mercies. To earn your trust and friendship, and then convince you to expend your Sheason arts on my behalf . . . leaving none for yourself.” She paused again, looking up at me with deep regret. “I was to keep you weak, so you would die.” I understood her look of shame when she said, “I am your third cruciation.”

My heart was hammering from the revelation of her betrayal. And I did feel parted. Parted from trust and loyalty. Parted from a friend. Our days and evenings together hadn’t been the idling of hours. She’d filled that time with meaning, companionship. Dear absent gods, she’d given me the tools and will to suffer through the brands. This secret we’d shared . . . it was intimate. Lifesaving.

I was sick at heart, weaker in spirit than I’d been since my first day of cruciation. And it had nothing to do with the pain in my body. I had lost faith in people. And I didn’t give a damn just then about retrieving the ThousandFold steel.

Then, looking at her pitch-covered cheeks, I remembered the expression on her face just before she’d begun teaching me Valutara. It had shown a weighing of consequences for betraying some trust. Looking at her now, my thinking cleared. “Teaching me the footings of Valutara . . . that wasn’t part of your plan, was it? Otherwise you wouldn’t have been punished.”

“My punishment was light,” she replied dismissively.

I began to smile, tempering it only so she wouldn’t feel mocked. “Your betrayal is incomplete, though, isn’t it? Incomplete because you gave me tools to cope with the pain, so I was able to avoid death.”

“My punishment was light,” she repeated.

It was hard to imagine she was being honest. She would be disfigured when the pain of these burns was long behind her. Her face was ruined. The skin a man would see when she removed her shirt would be a layer of raised tissue that would catch the light with a dull gleam. There would be long shame, and loneliness.

Her duplicity had been meant to break my spirit if I was able to withstand the simpler cruciations of the body. In that moment I had caught another glimpse at the deeper part of Talenfoier. A truer part. A part closer to the refinement it was meant to cause.

But something had changed during our evening walks. We had become friends. And my friend had just been painted down with hot pitch for helping me.

I didn’t wait or ask her permission. I settled my mind and aligned my own inner strength. I focused my thoughts on healthy tissue, and gave my rendering the full energy of my body. I caused the pitch to peel away and drop like a shell from her renewed skin. I took private pleasure in that image.

After healing her physically, I imparted to her my thanks. And so that she would understand some of why I did all this, I shared with her a few memories. I wished to place in her heart some context for the person I was. So, I shared losses. The deepest kind. And I shared nights of small-hour conversation, the kind friends have when the world sleeps and they speak of their most intimate thoughts. Thoughts they don’t admit in the light of day, when they would seem too fanciful to be taken seriously.

As I performed my rendering, I watched the look on her face pass from gratitude to horror to concern. Her concern, I knew, came because I would have nothing left to brace myself against the Talenfoier brands.

When I was through, I slumped over her, spent. Entirely spent. I would have to rest before even standing.

“Are you all right?” There was strain in her voice, as if she was holding back what she really wanted to say.

I nodded. It was all the reassurance she needed to let go her concern.

“You shouldn’t have.”

I shook my head, smiling weakly. “Of course I should.”

“No, you shouldn’t.” This time, I caught the quiet anger and disappointment in her disapproval.

Her reaction surprised me, which confirmed how little I actually understood Talenfoier. But I still felt like she was being rather ungrateful. “I just—”

“You robbed me of bearing marks I’d earned,” she said. “What do you imagine those who tarred me will say when they see my unblemished face?”

My anger coiled, giving me back a bit of vigor. I sat up. “So what have we been doing all these days, on all these evening walks? You say you wanted me to help. But that help isn’t good enough for you? Sounds like a warm case of hypocrisy to me.”

I’d expected a bitter retort to that. Maybe a hard set of knuckles across the bridge of my nose. And frankly, I’d have preferred either to the deeper disappointment I saw creep into Seelia’s face. It’s an awful thing for a man to see from a woman he cares about.

When she spoke, her voice came softly, as a teacher with endless patience. “I understood the possible consequences of my choice to show you the footings of Valutara.” She gave a sad smile. “I would not have been ashamed to be seen with the scars of that choice.”

My head began to spin, and I started to pant from the effort of merely holding myself upright.

“I’m sorry,” I said through a stuttering breath. “I had to do something. The thing that came to me was to restore your . . .”

Her eyebrows went up. “My what? Beauty? Confidence?” Her laugh came easy and comforting, like a babbling brook.

“Apparently I know as much about women as I do Talenfoier.” We both smiled quite genuinely at that.

When smiles were gone and silence returned, she gave me an apologetic look. “I’m only sorry for my deception . . .”

My strength gave out. I slumped forward again, resting my head against her bare breast, much as an infant does when he’s too tired to hold his head up. “I think I have the better of the exchange.”

“And how’s that? More arrogance, I’ll wager.”

“I’ve introduced an idea here in Darles Hem.” I had that sweet feeling of being aboutto share something deeply true. “An idea stronger than owning your pain, bearing it well. Stronger even than Talenfoier. Or Valutara.”

“And what’s that, my foolish friend?” Her words had smiling in them.

“A little succor, I guess. Gentleness.”

“Folly, they’ll say,” Seelia remarked. With the side of my face against her chest, I could feel her words when she spoke.

“Mercy is what they felt, though. Those who we walked in the evenings to find. They won’t forget it. And they may just decide to do the same for someone else.”

“It’s almost as if you planned it so,” she said, chuckling low.

I shook my head against her breast. “A beautiful accident is all.”

There were a few short hours before I’d return to Jaimen’s chair and take hold of the pegs. I thought more about warp tension in a loom as Seelia softly spoke, instructing, going a shade deeper in her teaching of Valutara.

. . . remove lies. Lies breed fear. In their absence, you make more room for your true self. Holding on to . . .

I could feel her compressing much into those hours, trying to prepare me. At one point I thought I heard her say, It shouldn’t be done like this. Might do more harm than good. If you know the Fairsmith texts, recall the tenets known as Backward Walking, there are correlates that may help . . . You are such a babe . . . But it all sounded far away, like a song heard from just below the surface of a still lake. I might have gathered a helpful hint or two. I don’t know.

Mostly I was content in the embrace of a friend. That seemed enough.

“A Beautiful Accident” copyright © 2015 by Peter Orullian

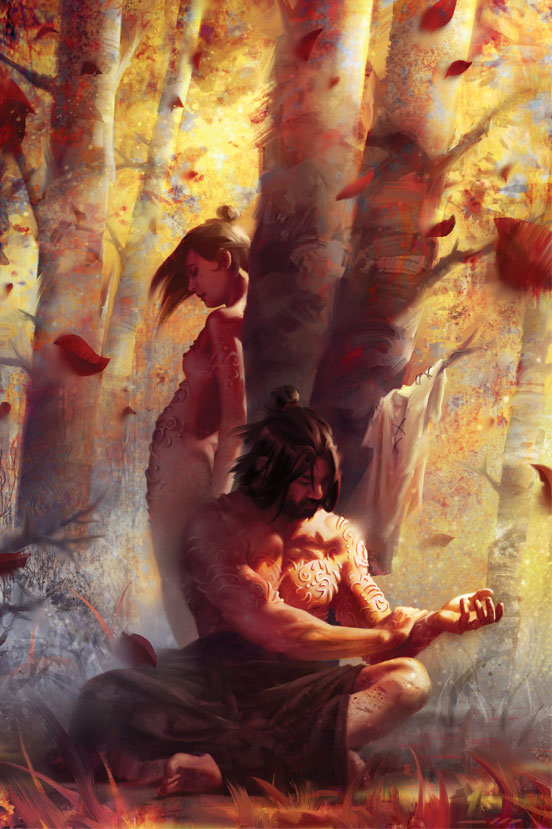

Art copyright © 2015 by Tommy Arnold