Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s original stories.

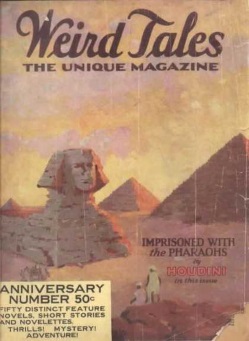

Today we’re looking at “Under the Pyramids,” written in February 1924 and first published (as “Imprisoned With the Pharaohs” by Harry Houdini) in the May-July 1924 issue of Weird Tales. You can read the story here. Spoilers ahead.

“It was the ecstasy of nightmare and the summation of the fiendish. The suddenness of it was apocalyptic and daemoniac—one moment I was plunging agonisingly down that narrow well of million-toothed torture, yet the next moment I was soaring on bat-wings in the gulfs of hell; swinging free and swoopingly through illimitable miles of boundless, musty space; rising dizzily to measureless pinnacles of chilling ether, then diving gaspingly to sucking nadirs of ravenous, nauseous lower vacua… Thank God for the mercy that shut out in oblivion those clawing Furies of consciousness which half unhinged my faculties, and tore Harpy-like at my spirit!”

Summary: Harry Houdini, magician and escape artist, relates an adventure from his 1910 tour of Egypt. He cautions that Egyptological study may have combined with excitement to overstimulate his imagination — surely the ultimate horror of his ordeal couldn’t have been real. In fact, it has to have been a dream.

Though he and his wife hoped for anonymity, another magician piqued him en route, and he blew his cover by performing superior tricks. No doubt the chatter of fellow passengers heralded his arrival throughout the Nile Valley.

With its European trappings, Cairo initially disappoints Houdini. He engages a guide, Abdul Reis el Drogman, who impresses with his hollow voice and Pharaoh-like aspect. After glorying in the splendors of the medieval Saracens, our tourists yield to the allure of “the deeper mysteries of primal Egypt” and head for the pyramids and the enigmatic Sphinx. Houdini speculates about Khephren, who had his own face carved onto the Sphinx. But what were its original features? What about legends of caverns deep below the hybrid colossus? And let’s not forget Queen Nitokris, who drowned her enemies in a temple below the Nile and may still haunt the Third Pyramid.

That night Abdul Reis takes Houdini into the Arab quarter. The guide gets into a fight with a young Bedouin. When Houdini breaks up their scuffle, they decide to settle their differences atop the Great Pyramid, in the pallid small hours when only the moon overlooks the ancient plateau. Thrilled by the idea of such a spectacle, Houdini volunteers to second Abdul Reis.

The fight seems almost feigned. The combatants reconcile swiftly, and in the drinking that follows, Houdini becomes the center of attention. He wonders if certain Egyptians might resent a foreign magician, and sure enough, the Bedouins suddenly seize and bind him. Abdul Reis taunts him: Houdini’s magical gifts will soon be tested, by devices much older than those of America and Europe.

Blindfolded, Houdini isn’t sure where his captors carry him, but they can’t have gone far before they lower him into a deep burial shaft—the rope seems to descend miles into the earth before he swings free in the very “gulfs of hell.” Naturally he faints.

He comes to in blackness, on a damp rock floor, hoping he’s really in the Temple of the Sphinx, near the surface. As he starts to free himself, his captors release the rope. It falls in a crushing avalanche that confirms the hideous length of Houdini’s descent. Of course he faints again and dreams about such pleasant Egyptian lore as composite man-beast mummies and the ka, a life-principle separate from body and soul which is said to persist in the tomb and to sometimes stalk “noxiously abroad on errands peculiarly repellent.”

Houdini wakens again to find the mountain of rope gone and his body wounded as if by the pecking of a giant ibis. Huh? This time his escape from bondage goes unhindered. In the otherwise featureless dark, he follows a fetid stream of air he hopes will guide him to some exit. He tumbles down a flight of huge stone steps. Third bout of unconsciousness ensues.

He comes around in a hall with cyclopean columns. The enormous scale of the place troubles him, but he can only crawl on. Soon he begins to hear music played on ancient instruments—and, worse, the sound of marching feet. He hides behind a column from the light of their torches. He wonders at how dissimilar pedal extremities – feet, hooves, paws, pads, talons – can tramp in perfect unison, and avoids looking at the approaching procession. Too bad the torches cast shadows: hippopotami with human hands, humans with crocodile heads, even one thing that stalks solemnly without any body at all above its waist.

The hybrid blasphemies gather at a vast, stench-blasting aperture flanked by two giant staircases – one of which Houdini must have fallen down earlier. Pharaoh Khephren – or is it Abdul Reis? – leads them in unholy worship. Beautiful Queen Nitokris kneels beside him. Well, beautiful except for the side of her face eaten away by rats. The crowd throws unmentionable offerings into the aperture. Does it conceal Osiris or Isis, or is it some God of the Dead older than all known gods?

The nightmare throng is absorbed in raptures. Houdini creeps up the staircase, to a landing directly over the aperture, when a great corpse-gurgle from the worshippers makes him look down.

Something emerges from the aperture to feed on the offerings. The size of a hippo, it seems to sport five hairy heads with which it seizes morsels before momentarily retreating into its den. Houdini watches until more of the beast appears, a sight that drives him in mindless terror up higher staircases, ladders, inclines, who knows what, for he doesn’t come back to his senses until he finds himself on the sands of Gizeh, dawn flushing the Sphinx whose face smiles sardonically above him.

Houdini thinks he knows now what the sphinx’s original features might have been. The five-headed monster was the merest forepaw of the God of the Dead, which licks its chops in the abyss!

What’s Cyclopean: The masonry of the pyramids. Which, actually… yes. That is legitimately cyclopean. Also an unnavigable hall deep below the Libyan desert. It’s hard to tell whether this is as appropriate; it’s very dark. In addition, we get a “cyclopic” column and a “Polyphemus-door.”

The Degenerate Dutch: Poor sad tourists, Egypt isn’t picturesque enough to meet your expectations. It’s all too European. Yes, dear, we call that colonialism. Can you spell ‘colonialism’? Eventually, one might find the delightful Arabian Nights atmosphere that any visit to the “mysterious east” is all about. We call that orientalism. Can you spell… Let’s not even get into the “crowding, yelling, and offensive Bedouins who inhabited a squalid mud village some distance away and pestiferously assailed every traveler.”

Mythos Making: Nitokris, Lovecraft’s favorite foe-drowning pharaoh, appears in person here. So our friend from “The Outsider” must be around here somewhere, too, right?

Libronomicon: No books. Maybe there are books in the tombs?

Madness Takes Its Toll: Houdini is very sensible in his reactions to the whole thing—particularly so if he’s wrong about it being a dream. Though there is all that fainting…

Ruthanna’s Commentary

I have mixed feelings about this story. On the one hand, it’s just plain fun. Houdini was a consummate showman, and having Lovecraft turn his voice up to 11 doesn’t hurt. And he makes a fun change from Lovecraft’s usual narrative voice, if only because how calmly he explains that it all must have been a dream. He doesn’t act nearly as desperate to disbelieve as most of our protagonists, and is more persuasive as a result—though not so persuasive as to ruin the story.

Plus, there’s the point where I dropped the computer yelling: “There bloody well is not any tradition of resolving disputes on top of the Great Pyramid! That is the stupidest plot device ever!” And then it turns out to be a scam that makes Houdini look like an idiot. Apparently real-life Houdini thought this was pretty funny, too.

Speaking of tattered cover stories, this was originally published under Houdini’s own name. Did anyone pick up this story and not catch the ghost writer on his second “cyclopean?”

And but so. “Pyramids” is also orientalist enough to cause intense eye-rolling in a modern reader. Lovecraft doesn’t dive particularly far below his contemporaries—the tropes here were common for decades afterwards, and you can still find them in modern work without looking too hard—but that doesn’t make them less annoying. Oh, the poor Europeans, in search of the fabulous Arabian Nights, getting caught up in exotic dangers. Oh, the predictable delights of the Mysterious East. Oh, the stereotyped tropes of the bazaar.

A couple of things mitigate the effect, though, at least a little:

- The fabulous pleasures of the east do not include exoticized women. Unless you count Nitokris, who remains awesome as ever.

- Lovecraft waxes similarly rhapsodic about New England architecture, if you catch him in the right mood, and supposedly familiar territory certainly isn’t short on exotic dangers.

- Khephren-as-villain is, in fact, Herodotus’s fault. In fact, a fair portion of this story is Herodotus’s fault.

And fourth—as in any number of Lovecraft’s other stories—it’s not too hard to flip the narrative of the insecure imperialist and sympathize with those on the other side. That narrative is pretty overt here. Houdini, great modern secular magician, goes to Egypt preceded by rumors of his prowess. And the most ancient inhabitants of that land, long overrun by Houdini’s people, decide to show him that their power is not entirely lost. Scary stuff, from the conqueror’s point of view.

Kind of appealing, from the other direction. Khephren and Nitokris and their followers can’t be any more thrilled by Cairo’s Europeanization than our tourists. Lev Mirov, on Twitter, recently talked about how so much “horror” is the horror of the broken status quo: “I can’t ever forget early spec horror is based on externalizing fear of people like me… In my stories, when the gods & ghosts come back roaring, they come for the sick, the wounded, the hungry, & give them gifts to play fair.” There’s definitely some of that going on here—though the old pharaohs may not be all that interested in stopping at “fair.” Then again, they don’t make it all that difficult for Houdini to get away and report on their power—and however much he denies its reality, that report should make listeners at the top of the modern hierarchy just a little nervous.

Finally, on an unrelated note, I’m left wondering: When did it stop being okay for protagonists to faint? I feel like there’s some point mid-century when you can no longer have your narrator, especially an overt “man of action,” fall unconscious without good medical cause. And also: Did people—people not wearing too-tight corsets—actually used to swoon whenever startled? Or is it just a leftover trope from romantic poetry?

Anne’s Commentary

Although his name isn’t mentioned in the text of the story, today’s narrator is far from anonymous – in fact, he’s quite the celebrity, no less than escape master Harry Houdini! In 1924, Weird Tales founder J. C. Henneberger commissioned Lovecraft to ghost-write a story for Houdini, paying the princely sum of $100, the biggest advance Lovecraft had received to date. Lovecraft felt Houdini’s tale of Egyptian adventure was a fabrication, but he took on the task when given permission to alter it. Alas, his own researches into Egyptology appear to have brought a curse down on the work. En route to his wedding, Lovecraft lost the manuscript in Union Station, Providence; much of his Philadelphia honeymoon was spent retyping it.

Writers will feel his pain in retrospect.

No one answered Lovecraft’s lost-and-found ad in the Journal, which is apparently the way we know the original title of this story, published as “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs.” I like to think that manuscript still resides in a Providence attic, tied round with black ribbon and rubbing pages with an unknown copy of the Necronomicon, or at least De Vermis Mysteriis.

Curse aside, Houdini liked Lovecraft’s story enough to hire him for other projects, including a book left unfinished at the magician’s death, The Cancer of Superstition. Robert Bloch expanded on Lovecraft’s weird Egyptology in stories like “The Fane of the Black Pharaoh.” He speculated that the god in the aperture wasn’t the Sphinx but Nyarlathotep. I can deal with that. I think just about anything horrible and awesome is an avatar of Nyarlathotep, He of a Billion Zillion Faces.

The travelogue opening of Pyramid reminds me of the Dreamlands tales, especially “The Doom that Came to Sarnath,” also heavy on exotic description. Houdini makes a good Lovecraft character of the bolder and more active subclass: the later Randolph Carter, for example, or the unnamed horror-seeker of “The Lurking Fear.” Curiosity drives him, and a taste for the extraordinary. He’s also prone to lapses of consciousness, fainting so frequently that the character himself remarks on it with humor – perhaps to beat us readers to the laugh.

As often in Lovecraft, the lapses are as much structural convenience as psychological verisimilitude. Faints save time and space. We don’t have to make the whole rope-dangled descent with Houdini – after we’ve gotten to the good part where he swings in cavernous space, we can skip ahead to him waking on a damp rock floor somewhere. He has to stay awake long enough to doubt the length of descent and then to have the doubt removed by the fall of the monstrously long rope. Then he has to faint again, so doubt can be re-established by the rope’s removal. Also we need him able to think Abdul and Company responsible for his fresh wounds, even though they seem to have been made by a gigantic ibis. Or, we’ll eventually suppose, something with the head of an ibis.

Faints are also useful as excuses to dream and/or feverishly speculate by way of info-dumping. Houdini’s dreams are actually prophetic. He sees Abdul Reis in the guise of Khephren, a pharaoh Herodotus painted as particularly cruel and tyrannical. He envisions processions of the hybrid dead. He even imagines himself engulfed in an enormous, hairy, five-clawed paw, which is the soul of Egypt itself. During the second faint, his dreams run on the tripartite division of man into body and soul and ka, and on how decadent priests made composite mummies. The third faint gives Houdini a chance to speculate that, hey, maybe he never fainted at all – the faints were all part of a long dreaming coma that started with his descent into the earth and ended with his awakening under the Sphinx. Yeah, yeah, it was all a dream, that most execrable of fictional endings!

Except that the reader must suspect it wasn’t a dream, any more than was Peaslee’s descent into the Yithian ruins, or Randolph Carter’s adventure in the Florida swamp.

Houdini’s fourth lapse is the sort of kinetic delirium Lovecraft employs again and again. How many of his heroes find themselves removed from point B back to point A without remembering how they managed the journey? Which, of course, strengthens any option of thinking “oops, must have been a dream or hallucination.” Peaslee falls into this category. So does the Carter of “Statement.” Continue the list in the comments for frequent-cosmic-flyer points!

Anyhow, an effective story once we get underground, where truths lie and where, even partially glimpsed, they’re more than terrible enough. So terrible, in fact, that they can make us, like Houdini, feel “terror beyond all the known terrors of earth – a terror peculiarly dissociated with personal fear, and taking the form of a sort of objective pity for our planet, that it should hold within its depths such horrors.”

Now that’s Lovecraftian angst for you!

Next week, we finally tackle “The Horror at Red Hook.” Gods protect us. Trigger warning for Lovecraft’s nastiest phobias and prejudices on full display.

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian novelette “The Litany of Earth” is available on Tor.com, along with the more recent but distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land.” Her work has also appeared at Strange Horizons and Analog. She can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal. She lives in a large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “Geldman’s Pharmacy” received honorable mention in The Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror, Thirteenth Annual Collection. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” is published on Tor.com, and her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen. She currently lives in a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island.

This was one of the first Lovecraft stories I was exposed to (as “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs”) in that Scholastic anthology I’ve mentioned. At the time, it scared the crap out of me and set me up perfectly for “Innsmouth” to send me over the edge. In fairness, I was 10 or 11 and toward the end of my Egyptology phase (which, since it was the early 70s included a bit of pyramidiocy). This time out, I got bogged down in the adverbs and adjectives and had a hard time maintaining my interest. Maybe I just wasn’t in the right mood.

I rather doubt non-corseted human beings had a greater propensity for swooning. It certainly doesn’t fit with Houdini at all, for whom it would have been something of a health hazard. Chained upside down in a trunk and underwater would be a really bad time to lose consciousness. Swoons do function as Ruthanna discusses and they also simplify difficult transitions. Dante uses them a couple of times, but they’re highly symbolic. Homer makes Odysseus pass out a time or two, I think, but he at least had the excuse of physical exhaustion. HPL just goes to extremes here. OTOH, exposure to pyschologically overwhelming experiences could trigger brief fugue states, I suppose.

In later years, I’ve always assumed the Sphinx was another of Nyarlathotep’s forms. He’s the main actor among humans, after all, and the man-headed lion ties in nicely with a couple of his better known forms.

Also, HPL has another attack of Absurdly Spacious Sewers here. (Don’t click that, it’s TV Tropes and will eat your life.) He’s awfully fond of that trope, but then it was something of a staple in the pulps.

This story… is about as good as a story ghostwritten for a celebrity can be. The “merest forepaw” creature is so very atmospheric, I just wish it had been worked into something rather better.

Weird Tales: As pictured, it got the cover of May-June-July 1924 with the title “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs”, an issue with not one but two further Lovecraft stories: “Hypnos” and “The Loved Dead” (with C. M. Eddy). It was reprinted in June-July 1939, along with another couple by Lovecraft, “The Howler” and “Celephais”, two by Robert E. Howard, “The Hills of Kandahar” and the second part of Almuric serial, and Clark Ashton Smith’s “The Willow Landscape”.

Today’s birthday: August Derleth, 1909-1971. I’m planning to half-celebrate.

Positive moments in Lovecraft’s handling of race and ethnicity, #1: There’s a case for arguing that this is a Lovecraft story with a Jewish protagonist: according to the Jewish Virtual Library, Houdini was born Ehrich Weiss and was the son of the first rabbi in Appleton, Wisconsin.

A thing I found just after clicking “Post”: http://bit.ly/1w8hGXX

Re flipping the viewpoint: “Oh my Glob, will you quit picking at the brand-new decorations on my balcony and go home already? And stop that shrieking this instant! Ugh, anthropoids.”

I haven’t had much to say about recent posts, but want to thank you agaifor introducing me to many of Lovecraft’s lesser-known stories, the ones which are rarely if ever mentioned among the casual fandom (as far as I’ve seen) but weird and wondrous in their own way.

Next week may be rather grim, though…

I will always love this one, because I will never forget the first time I read it, when I got to the bit about the thing with the five maybe-heads, and I struggled to picture that, to place it in Egyptian legends that I know, and, when that failed, just to keep an open mind and mentally ‘see’ the scene accurately. Then, when it got to the reveal, my perspective on the whole thing turned inside out, basically literally. It was a total reframing and recoalescing of how I’d been picturing everything, and it hit as hard as any horror reveal I can remember. One of the better uses of simple physical description I can think of, and one which doesn’t cheat, since there is no way we could have more information than the protagonist.

I’ve probably mentioned before that Nitocris is the star of Lord Dunsany’s magnificently creepy play ‘The Queen’s Enemies’, but it’s still very much worth reading.

DemetriosX @@@@@ 1: Good point–I hadn’t even been thinking of Dante and Homer, but of the more recent Shelley. Frankenstein is even worse about the whole swooning thing, and when I first read that book I assumed she just spent too much time hanging out with romantic poets.

I do love me some absurdly spacious sewers, and continue to maintain that gods who build in extra dimensions have more excuse for them than most.

SchuylerH @@@@@ 2: Did Lovecraft know that Houdini was Jewish, though? After all, he changed his name to hide it. (Much like my grandfather, whose desire for an easier job hunt we have to thank for our regular invitations to Gordon clan reunions in Scotland.) Something to be done there with true names and the importance of keeping them secret…

AeronaGreenjoy @@@@@ 4: We read it so you don’t have to. And yeah, we’re having fun with the more obscure ones, too.

Rush-That-Speaks @@@@@ 5: Okay, that’s enough to get me to go track down some Dunsany.

@6: From what I’ve read, while Houdini didn’t want to be thought of as immigrant, he didn’t make any substantial efforts to hide being Jewish: he was, apparently, one of the most active members of the Jewish Theatrical Guild.

I suspect that, in this case, Lovecraft and Houdini’s shared interests, particularly when it comes to debunking pseudoscientists, may have outweighed their differences. I’ve seen reference to another ghostwriting job for Houdini, a non-fiction book called The Cancer of Superstition, which Lovecraft and Eddy were working on at the time of Houdini’s death and to an anti-astrology article by Lovecraft.

At the very least, Houdini’s experiences with Lovecraft were, while they lasted, better than those with Arthur Conan Doyle: http://skeptoid.com/episodes/4430

Interesting as always.Some comments:

1.SchuylerH:”@6: From what I’ve read, while Houdini didn’t want to be thought of as immigrant, he didn’t make any substantial efforts to hide being Jewish: he was, apparently, one of the most active members of the Jewish Theatrical Guild. ”

Yeah, I read a biography of Houdini a while back, and, from what I can recall, Houdini was quite open about being Jewish.He would, for example, refer to his Jewish background in a casual fashion when talking to people like Conan Doyle.So, I think that it is quite likely that Lovecraft did know that Houdini was Jewish.

2.RE: the story,I thought that it was surprisingly good.Sure, it’s packed full of descriptive passages that read as though they were lifted from the nearest Baedeker, but Lovecraft manages to make it work.To my mind, it’s easily the best of Lovecraft’s ghostwriting jobs.

3.Influenced by:Joshi suggests that some of the tale’s atmophere derives from Gautier’s “One of Cleopatra’s Nights.”

4.Random Houdini note: He had an affair with Jack London’s widow

“Under the Pyramids” can support only a dream (or hallucination)

interpretation, unless the reader is inclined to accept that Pharaonic magic

actually works. There are too many elements inconsistent with reality. The

cavern through which Houdini soars “swoopingly through illimitable miles of

boundless, musty space,” if taken literally, is certainly not geophysically

feasible: Giza, according to Wikipedia, is only 62 feet above sea level, so

essentially the whole void would be below sea level, the ultimate base level

beneath which virtually all cavities should be filled with water. And it

should be lethally hot at such a depth. Furthermore, miles of rope, or

anything close to it, would be far too heavy and bulky for a little troupe of

Bedouins to manage. Finally, the hybrid animal-headed monstrosities are

biologically incredible. HPL makes no effort here to supply the scientific

background that gave his science-fiction tales their air of authenticity.

At some point in The Words, Sartre describes the kind of texts he was writing when he was a child: he would for instance describe the adventures of whalers, and then would segue to an excerpt of some encyclopedia article on whales, thinking the transition was seemless. That’s cute when it comes from a child, but that’s really awkward here. Beside, Carter had just discovered king Tut’s tomb, egyptomania was at its height: who could possibly ignore this basic information about the pyramids?

Apart from that, I liked the moment the rope doesn’t stop falling (and if it wasn’t a dream, where did they hide the kms of rope when they went to the pyramids?). But when you are lost in an unknown labyrinth and you have an infinite rope, it’s a minimum to use it as an Ariadne’s thread.

The first fainting made complete sense to me: he is tied up, maybe head down (which is just Houdini’s natural state), but for a really long time, and maybe with important variation of air pressure (but that would require the setting to make sense, which it doesn’t): in these conditions, it’s hard to remain conscious.

I always liked this story. Edgar Cayce (along with various antique sources) predicted the existence of a secret chamber below the Sphinx and there is some evidence something like that may exist, although not nearly on the predicted scale. This Smithsonian article is a good overview of the Sphinx’s history:

http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/uncovering-secrets-of-the-sphinx-5053442/?onsite_source=relatedarticles&page=1

I like the idea that Lovecraft applied the same “Orientalism” to New England that he did to Egypt. I like the idea of someone from Egypt reading Lovecraft’s New England tales and thinking, “I’m so bored here! I wish I lived in exotic New England!” :P

Late to the party as always…

Does anyone else interpret the “unmentionable offerings” the hybrid mummies throw to the God of the Dead as bits broken off their own bodies, or is that just my own brain going to a really weird place?

I’ve always wondered why Houdini of all people couldn’t free himself from the rope without it having to be ibispecked to pieces.