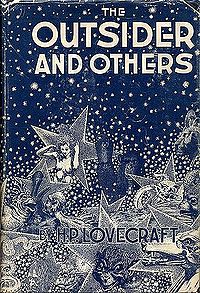

Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s original stories. Today we’re looking at “The Outsider,” written in 1921 and first published in the April 1926 issue of Weird Tales.

You can read the story here. Spoilers ahead.

“Wretched is he who looks back upon lone hours in vast and dismal chambers with brown hangings and maddening rows of antique books, or upon awed watches in twilight groves of grotesque, gigantic, and vine-encumbered trees that silently wave twisted branches far aloft. Such a lot the gods gave to me—to me, the dazed, the disappointed; the barren, the broken.”

Summary: Our nameless narrator lives alone in an ancient castle. Apart from a barely recalled nurse (shockingly old and decayed), he has seen no humans save those in his antique books, and he has never heard a human voice including his own. The castle has no mirrors, but he must be young, since he remembers so little.

Apart from the books, the castle has brown hangings, damp and crumbling corridors, and stone crypts strewn with skeletons. It smells like the “piled-up corpses of dead generations.” A putrid moat surrounds it, and beyond the moat, a forest of huge and twisted trees whose canopy blocks out the sun and moon and stars, leaving the narrator’s world in constant twilight.

To relieve the darkness, the narrator stares at candles. To escape his solitude, he dreams of joining the revels he reads about. He has tried to find a way out through the forest, only to be driven back by the fear of losing himself in its black avenues. Longing for the light drives him to a desperate resolve: He will climb the only castle tower that rises above the treetops, even though its steps give out partway up.

The ascent of the tower’s interior, tenuous finger-grip by precarious foothold, takes an eternity. At last the narrator finds a trap door that opens into a stone room—it must be an observation chamber high above the forest. Yet it has no windows, only marble shelves that bear disturbing oblong boxes. There is one door, which he wrenches open. Beyond it, steps lead to an iron gate, through which a full moon shines.

The narrator opens the gate with care, fearful of a great fall. To his astonishment, he finds himself not at the pinnacle of the tower but at ground level, in a region of slabs and columns overlooked by a church. The craving for light and gaiety drives him onward, through a land of ruins to a castle in a wooded park. Somehow he knows the castle, though it has been altered. As luck will have it, a ball is in progress. He walks to an open window and stares in at an oddly dressed company. The ball-goers’ merriment dissolves into screaming panic the moment he steps into the room; all flee, leaving him alone, nervously looking for the terror that precipitated their stampede.

Something stirs in a golden-arched doorway leading into a similar room. The narrator approaches and screams—his first and last vocalization—when he perceives the abomination beyond the arch. It’s what the merciful earth should always hide, a leering corpse rotted to the bones!

In attempting retreat, the narrator loses his balance and stumbles forward. His outstretched hand encounters that of the monster. He doesn’t scream again, for full memory returns to him in a soul-annihilating flood, and his mind is officially blown. He runs back to the churchyard and the tomb from which he emerged, but cannot lift the trapdoor to the underworld. Any regret is brief, since he hated the place anyhow. Now he sports with other ghouls upon the night wind and among Egyptian catacombs. The light is not for him, for when he stretched out his hand to that corpse’s, he touched not rotting flesh but the cold polished glass of a mirror.

What’s Cyclopean: Per last week’s discussion of unnameability, the monstrosity from which all flee is “inconceivable, indescribable, and unmentionable.”

The Degenerate Dutch: Nothing particularly egregious—the Egyptians might be startled to discover unnamed feasts of Nitokris beneath the Great Pyramid, but it isn’t necessarily a given that they’d be disappointed. (And there was, in fact, a while when she was supposed to be its builder—this would still have been one of the going theories in Lovecraft’s time.)

Mythos Making: Nitokris and Nephren-Ka are both pharaohs; Nitokris appears in Herodotus and may or may not be an actual historical person. She also shows up in Lovecraft’s collaboration with Houdini. Nephren-Ka is a servant of Nyarlathotep, per “The Haunter in the Dark.”

Libronomicon: The narrator learns (relearns?) all that he knows of the world from books.

Madness Takes Its Toll: The narrator appears to forget and remember his past at the same time, a neat psychological trick that’s more realistic than you might think.

Anne’s Commentary

This is one of Lovecraft’s most Poesque tales, from the narrative choice of a decayed nobleman, bookish and reclusive, down to the diction. It’s also one of his most dream-like pieces, for it proceeds with the intensity and logical illogic of nightmare. Sure, we could ask obvious questions, like, why does the narrator need a mirror to know he’s an animate corpse? Can’t he look down at his rotting hands, his deteriorating body? Or, how can he be so dense he doesn’t recognize a tomb, coffins, a graveyard, when he recognizes other earthly things, like a church and a castle?

In another kind of story, legitimate quibbles. Here, that logic-illogic of dream reigns—if we can’t accept its unruly rules, we might as well stop reading.

The epigraph is from John Keats and “The Eve of St. Agnes.” These particular lines fit the mood of Lovecraft’s story, but Keats’s erotically charged poem on the whole? I don’t sense a connection. Of Lovecraft’s own stories, “The Tomb” is a fine Poesque companion. There’s also mention of the sort of Egyptian haunts Lovecraft explores in “Under the Pyramids,” including a shout-out to the lovely if ghoulish Queen Nitocris. Oh, and the hard-to-climb tower reminds me of the Tower of Koth in Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath, with bats instead of gugs. Gugs, cooler; bats, far more survivable. Not that our narrator actually needs to survive.

Also of note, the moon in “Outsider” is FULL, a nice change from the usual GIBBOUS moon. The climax must be in contention for the most “in-”s and “un-”s, beating even “The Unnamable”: inconceivable, indescribable, unmentionable, unclean, uncanny, unwelcome, unwholesome, unspeakable, unholy, unknown, unnamed plus an “ab-” in abnormal.

I’m generally uneasy about reading between fictional lines for autobiographical confessions, and so I think it would be facile to conclude that Lovecraft speaks of himself in the famous line, “I know always that I am an outsider; a stranger in this century and among those who are still men.” Antiquarian tastes do not a Joseph Curwen make; and Lovecraft was very much on the inside of his own large coterie; and I doubt he considered himself anything less than a man, however he might secretly have yearned to be more than one, a Yith, say. But our loves and antipathies and anxieties are woven into our fictions, whether in bold red splashes or subtle gray undertones. The power of fiction lies in the commonality of these personal threads. Which of us hasn’t worried about being on the periphery of the “sunny world” or even feared we were lost deep within the “endless forest” of our bothersome personae? Which of us hasn’t had a social anxiety nightmare? Sure, we might just dream about going to class or work stark naked or something innocuous like that. Lovecraft takes his narrator, and himself, and us to the max: We show up at the ball, and you know what? We look SO HORRIBLE that everyone runs out of the place shrieking. They don’t even stop to laugh at us—we are beyond comedy and straight into horror show. Because, guess what, we are absolutely (or at least socially) dead to them.

That’s an even worse prom night than poor Carrie had. At least she got to be queen for a few seconds before the pig blood hit.

For me, the more evocative truth Lovecraft may be telling about himself in “Outsider” lies in the line, “I know that light is not for me, save that of the moon over the rock tombs of Neb, nor any gaiety save the unnamed feasts of Nitokris beneath the Great Pyramid; yet in my new wildness and freedom I almost welcome the bitterness of alienage.” I’m reading this as a declaration (conscious or otherwise) of Lovecraft’s literary bent, a proud acceptance that the genres in which he can excel are best perused by moonlight, full or gibbous. More, there’s a freedom in weird fiction that will lead him, and us, to places well worth the visit for people of our “wild” and “alienage”-embracing mindsets.

Finally, practical lessons to learn from this story. One: Always check yourself out in a full-length mirror before going to a big social event. If your castle doesn’t have a mirror, well, that should be telling you something right there. Either you’re really ugly, or you’re a vampire, or you’re an ugly vampire.

Although an ugly vampire —

Never mind, on to Lesson Two: Accept yourself, no matter how bad you think you look or are. You’re not the only ghoul in the world, so don’t retreat to that solitary castle in the lonely forest. Ride the night wind with the other ghouls and have dinner with Nitocris. She may serve some of those camel heels we talked about a few blog posts earlier, as well as hippo rump slow-roasted in papyrus leaves.

I think it’s hippo, anyway.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

My first reaction to this story was dismissive—the blatant angst of the narrator’s situation seemed overdone, his horrible revelation at the end too trite of a twist. After some while complaining about how I had nothing to say, I realized that at least part of my revulsion was the degree to which “Outsider” reminds me of my own juvenalia (albeit better-written). Story constructed to avoid the need for portraying real human interactions? Check. One-note emotional arc? Check. Lightly disguised allegory for author’s own perceived isolation from humanity? Check. My stories were more likely to involve cyberpunk assassins, but otherwise this felt embarrassingly familiar.

Once I get that self-conscious knee-jerk out of the way, there is in fact some interesting stuff here. The ending at first glance might feel like Lovecraft reached the big reveal and then went, “What now? Once you realize you don’t fit in with humanity, what do you do? I dunno, hang out with ghouls?” Which is an answer I found pretty appealing at 19. Those last couple of paragraphs are the first place where the story touches on anything from the Mythos, suggesting that the narrator escapes the terrible world of men and their rejection for the comforts of cosmic horror.

The idea that the Mythos can be actively welcoming is one I still find appealing, and one that Lovecraft himself rarely acknowledges quite so overtly. In fact, in some ways this seems to presage the more organically developed, and (I think) more effectively wondrous and shocking, end of “Shadow Over Innsmouth.” Step 1: discover horror. Step 2: reject horror. Step 3: Become horror, and learn to delight in the community of your fellows.

As in a lot of other places, Lovecraft’s complete lack of subtlety masks a degree of actual subtlety. The epigram is from Keats’ “The Eve of Saint Agnes.” As you might expect of Keats, it’s pretty wild and you should read it. Among other things, it involves a deadly and at least metaphorically supernatural banquet. (Keats is gonna bring up faery hosts in the middle of relatively ordinary events the same way Lovecraft is gonna bring up vast cosmic gulfs.) Then at the end we get two pharoahs—one from Lovecraft and one from Herodotus. Nitokris may or may not have existed, but if she did she pulled a serious Martin on her brother’s murderers. Our narrator may want to be super-careful at those sub-pyramidal parties. So it’s deadly, horrific feasts all around—right there on screen and by literary and historical allusion.

Kind of tempting to make an inferential leap and wonder if the narrator is the undead remnant of someone from one of those other feasts.

Speaking of that epigram, there is, in fact, something of the romantic poet about Lovecraft. Keats and company were brilliant poets, but they could get pretty purple when the mood suited, and no one ever accused them of emotional understatement. Too, there’s something about Lovecraft’s narrators that reminds me of Mary Shelley’s—maybe it’s the tendency to not quite pull off the whole man-of-action thing, and to swoon into a faint when confronted with horror.

Even at his no-one-will-ever-understand-me-I-can-never-fit-in gothiest, Lovecraft manages some interesting stuff.

Next week, join us for the first appearance of Lovecraft’s best-known (human) recurring character in “The Statement of Randolph Carter.”

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian novelette “The Litany of Earth” is available on Tor.com, along with the more recent but distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land.” Her work has also appeared at Strange Horizons and Analog. She can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal. She lives in a large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “Geldman’s Pharmacy” received honorable mention in The Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror, Thirteenth Annual Collection. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” is published on Tor.com, and her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen. She currently lives in a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island.