In this ongoing series, we ask SF/F authors to recommend five books based around a common theme. These lists aren’t intended to be exhaustive, so we hope you’ll discuss and add your own suggestions in the comments!

When Noam Chomsky challenged himself to write a sentence that was grammatically correct but made no sense at all, he came up with “Colorless green ideas sleep furiously.” Chomsky overlooked the human drive to make sense out of everything, even nonsense. There is poetry in his sentence, and, after a vertiginous moment of disorientation, we move rapidly from crisis to the discovery of meaning, with truths often more profound than what we find in sentences that make complete sense. There is magic in non-sense, for words turn into wands and begin to build new worlds—Wonderland, Neverland, Oz, and Narnia. Presto! We are in the realm of counterfactuals that enable us to imagine “What if?”

Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

“Important—unimportant—unimportant—important,” those are the words of the King as he tries to figure out which of the two “sounds best.” There he sits in a court of law, with the jury box upside down and “quite as much use one way or the other,” telling us that beauty trumps sense. When I was ten years old, I fell in love with Alice in Wonderland, in part because my stern, white-haired teacher told me that it was a book for adults not children, in part because it was there that I first learned about the wonders of disorientation.

Brothers Grimm, “The Juniper Tree”

Brothers Grimm, “The Juniper Tree”

When my children were young I read them a fairy tale called “The Juniper Tree.” I reached the part when the boy is decapitated by his stepmother—she slams the lid of a chest down on his head. I started editing and improvising like mad, especially when I saw what was coming: making a stew from the boy’s body parts for his dad’s supper. Fairy tales and child sacrifice? Cognitive dissonance quickly set in, and that’s what put me on the road to studying what Bruno Bettelheim famously called the “uses of enchantment.”

Hans Christian Andersen, “The Emperor’s New Clothes”

Hans Christian Andersen, “The Emperor’s New Clothes”

Almost everyone loves this story about a naked monarch and a child who speaks truth to power. What I loved about the story as a child was the mystery of the magnificent fabric woven by the two swindlers—light as spider webs. It may be invisible but it is created by masters in the art of pantomime and artifice, men who put on a great show of weaving and making fabulous designs with threads of gold. They manage to make something out of nothing, and, as we watch them, there is a moment of heady delight in seeing something, even when nothing but words on a page are before us.

Henry James, “The Turn of the Screw”

Henry James, “The Turn of the Screw”

What got me hooked on books? I remember a cozy nook where I retreated as a child into the sweet serenity of books only to be shocked and startled in ways I thankfully never was in real life. What in the world happened to little Miles in that uncanny story about a governess and her two charges? There had to be away to end my profound sense of mystification. It took some time for me to figure out that disorientation and dislocation was the aim of every good story. Keats called it negative capability, the capacity to remain in “uncertainties, mysteries, and doubts.”

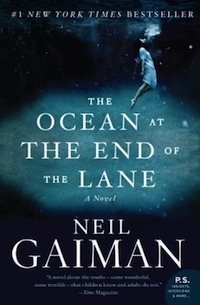

Neil Gaiman, The Ocean at the End of the Lane

Neil Gaiman, The Ocean at the End of the Lane

“I make things up and write them down,” Gaiman tells us. In this long short story, we travel with the narrator into mythical terrain. It dawns on us only ever so gradually that a path with briars and brambles can be a time machine drawing us back to a childhood. In a place charged with what Bronislaw Malinowski called a high coefficient of weirdness, we meet mysterious cats, along with a magna mater in triplicate, and also discover the healing power of recovered memories.

Maria Tatar chairs the program in folklore and mythology at Harvard. She is the author of many acclaimed books on folklore and fairy tales, as well as the editor and translator of The Turnip Princess, The Annotated Hans Christian Andersen, The Annotated Brothers Grimm, The Classic Fairy Tales: A Norton Critical Edition, and The Grimm Reader. She lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

How about “The Third Policeman” by Flann O’Brien? Some of Pynchon’s work could fall into this category as well (an argument could be made for “The Crying of Lot 49” or “Inherent Vice,” certainly).

Pynchon -yes. Borges – yes. The opening story of Again Dangerous Visions (Counterpoint of View by Hendery) yes to the max.

Interesting how often fairy tales end up on the list, full of dream logic that is nonsensical and yet consistent. Stream-of-consciousness fiction has that effect on me, too. As well as others: Jo Walton’s My Real Children is constantly playing on a theme of disorientation in the clash of memories of 2 alternating life-paths and the underlying desire (by reader, by protagonist) to reconcile everything into a single narrative.

I’d like to recommend Sukumar Ray’s Topsy Turvy Tales for sublime nonsense. If you can get an illustrated version then so much the better :-)

My Real Children, certainly, and Walton’s Among Others also qualifies.

Fire and Hemlock, by Diana Wynne Jones, also features a protagonist with two sets of memories, and a double-visioned reality: “Now Here” or “Nowhere”? In my end is my beginning…

There’s not much solid ground anywhere in Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House.

Pamela Dean’s “Secret Country” trilogy is about the reality of the things we make up, and our responsibility to the making.

And if we’re going to talk about making things up, let’s not forget the brilliant nonsense of James Thurbers’s The Thirteen Clocks. And the Golux in his indescribable hat; he makes things up, but he’s still the only Golux in the world, and never a mere Device.

I always thought Crowley’s books, Little, Big, and the Aegypt books, sort of fit this. On the surface they appear to be stories about characters doing things and interacting, much as in any other book, but there are constant little jumps through looking glasses, as it were, that they come across as dreams that seem to make sense when you have them, and then, when you try to explain them, it turns out to just be weird.

Not sure about “Nonsense,” but “Disorientation”?? — most definitely Danielewski’s “House of Leaves.”

There were passages in Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell that use reader disorientation to mirror the disorientation of characters in the story when dealing with the fairy world.

This is a stretch, but I’ll also suggest The Princess Bride. The disorientation was momentary, but a lot of fun. In particular I’m thinking about where Fezzik tries repeatedly to kill the Man in Black. After each attack Goldman describes the resulting gory death as if it had just happened, but then Fezzik’s slow mind (and the reader) catch up to the fact that the man in fact escaped.

(As these two examples show, I like it when the reader’s disorientation echoes that of a character in the story.)

The books in this entry seem to have disappeared! That’s delightful for the theme, but unhelpful for the potential reader. Can anyone help?