In his lifetime, author Felix Salten straddled many worlds: as a hanger on to Hapsburg courts, a member of various Viennese literary circles, the author himself of what is reportedly one of the most depressing pornographic novels ever written (tracking down a reliable English translation is tricky), an occasional political activist, and a fierce Zionist. For financial reasons, he was barely able to attend school, much less enter a university program, but he considered himself an intellectual. He loved Vienna, but saved his deepest love for Austria’s mountains and forests, becoming an avid hiker and cyclist.

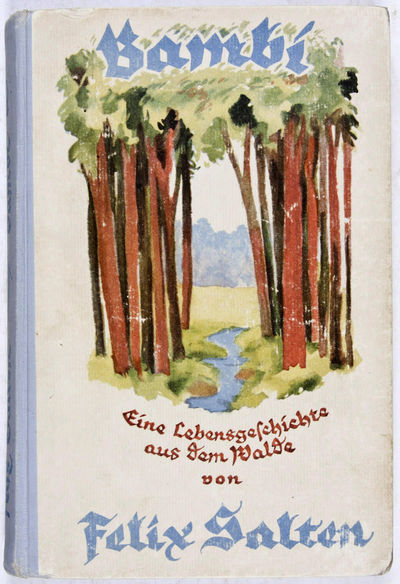

All of these blended together in his masterpiece, Bambi: A Life in the Woods, a deceptively simple story about a deer named Bambi and the animals he meets in the forest.

Bambi starts off quietly, with the birth of a little fawn in the woods. It is a happy moment for the fawn’s mother, a moment filled with birdsong and love, and yet, even here, some quiet, discordant notes are sounding. The different species of animals may be able to understand each other, but that doesn’t mean that they listen. The peace of the forest shelters the harsh cries of falcons and crows.

And although Bambi has his mother, he is at first completely isolated, unable to understand any of the voices that he hears. Slowly, his mother begins to introduce him to the forest, to the meadow, and to Him—the word, always capitalized, that the animals use for the human hunters in the woods. This includes explaining to Bambi what deer are (in a delightful passage that suggests that Salten also spent significant time not just with animals, but with three year old humans) and introducing him, bit by bit, to the concepts of beauty and danger and death. And, in a few short pages, to the idea of scarcity and hunger and fighting for food—even in a forest seemingly filled with abundance.

Bambi also meets other deer: his aunt Ena and her two children—Gobo, who is sickly, and Faline, a beautiful little deer who captures Bambi’s heart; Nettla, a cynical old deer with a caustic tongue; Ronno and Karus, two other young buck deer who become Bambi’s rivals; the various fathers, who sometimes run off with the mother deer, abandoning their children; and a majestic old stag, who knows something about Him. The deer also gossip about the other animals in the forest, particularly when those other animals die. And they discuss what, if anything, they can do about death.

As the seasons change into winter, food becomes scarce, and many of the animals weaken. The poignancy of this moment was probably heightened by Salten’s own memories: he had grown up poor and often hungry, and these passages have a harsh, bitter sharpness to them that almost certainly seems to be drawn from memory. Naturally, this is when He strikes, and many animals fall. Spring returns, with its abundance, as does life, and romance, and death.

And Him.

On the surface, Bambi: A Life in the Woods, is just a simple story about animals and fathers who regularly abandon their children. (I’m willing to give deer a bit of a pass on this; Salten, possibly less so.) It is also a powerful and unapologetic anti-hunting story. Claims that Bambi helped lead to a population explosion of white-tailed deer in the U.S. are pretty excessive (and in any case, would probably be more the fault of the Disney film than the book), but the book is certainly not written to build sympathy towards hunters, and many readers have responded to the text by deciding to never eat meat again. And on a surface level, Bambi is a celebration of the forests that Salten loved so dearly (I almost wrote “deerly” there, forgive me).

On the surface, Bambi: A Life in the Woods, is just a simple story about animals and fathers who regularly abandon their children. (I’m willing to give deer a bit of a pass on this; Salten, possibly less so.) It is also a powerful and unapologetic anti-hunting story. Claims that Bambi helped lead to a population explosion of white-tailed deer in the U.S. are pretty excessive (and in any case, would probably be more the fault of the Disney film than the book), but the book is certainly not written to build sympathy towards hunters, and many readers have responded to the text by deciding to never eat meat again. And on a surface level, Bambi is a celebration of the forests that Salten loved so dearly (I almost wrote “deerly” there, forgive me).

But more than any of this, Bambi is a study, not of death and violence precisely, but the response to that death and violence. The deer are, for the most part, helpless against Him. Oh, certainly, as Gobo and the dogs demonstrate, they have the ability to cooperate, at least for a time, with the hunters—Gobo even becomes a well fed, adorable pet, which later helps him attract a young deer companion who has never quite believed that the hunters are bad. But this—spoiler alert—does not work out all that well for Gobo.

Nor are the hunters the only threat: in winter, many of the animals starve, or nearly starve. We get drawn out, detailed descriptions of other deaths from animal hunters: crows, falcons, ferrets, foxes. These deaths, too, are mourned by the animals, who eventually believe that “There was no longer either peace or mercy in the forest.” But the most terrifying threat remains Him.

That a murderous fox later faces his own death from Him is only small solace, especially since that scene is one of the most graphic in the book. Nor does it help that the animals know very little about Him: only legends and gossip and rumors. They aren’t even sure how many arms He has—some say two, some say three—with the third one able to spit out fire.

So how can the animals respond, given that they are no match for Him, and given that even without Him, they will inevitably die?

Some of the deer and the dogs suggest cooperating, and becoming pets—but that, as Gobo’s life demonstrates, is only a temporary solution. In an extraordinary passage, dying leaves try to convince themselves that they are still beautiful, that other things besides aging and winter can kill, and that they need to remember the sun. Bambi, meanwhile, abandons Faline and finds himself spending more and more time alone. This is, of course, partly a reflection of the actual habits of male roe deer, who do not typically remain with their mates or spend a lot of time with other animal species. But it’s also a sign of clinical depression, a typical response to feelings of helplessness. Bambi survives, but not undamaged.

These questions were ones that Salten, as a Jewish resident of late 19th century and early 20th century Vienna, pondered regularly. Keenly aware of the difficulties faced by many eastern European Jews—his own family left Budapest because of these difficulties—he was a Zionist, eager to help other Jews return to the Palestine area. But he did not, and could not assume that emigration was an option for all. He himself, with a life and friends in Vienna, did not move to Palestine. He fiercely argued against cultural assimilation, believing that Jews should celebrate their identities through the arts, and wrote texts for a general audience, and worked with the Hapsburg court.

It would be a bit too much, I think, to describe Bambi, as the Nazis later did when they banned it, purely as “a political allegory on the treatment of Jews in Germany.” (Their words, not mine). I think far more is going on here, particularly when it comes to discussions of death and survival.

But at least one part of Bambi is explicitly an argument against cultural assimilation with oppressors: no matter what the deer or other animals do, they remain, well, animals. Gobo’s story is perhaps the best example of this, but to drive home the point, Salten returns to it again in a passage late in the book, when several forest animals turn on a dog, accusing him—and cows, horses, and chickens—of being traitors, an accusation fiercely (and rather bloodily) denied by the dog, Salten has this:

“The most dreadful part of all,” the old stag answered, “is that the dogs believe what the hound just said. They believe it, they pass their lives in fear, they hate Him and themselves and yet they’d die for His sake.”

Perhaps no other part of Bambi reflects Salten’s politics more than this.

But perhaps no other part of Bambi reflects his beliefs more than the passage where Bambi and the old stag encounter a dead hunter in the woods, finding, finally, a touch of hope. The forest may be dangerous. But even in its wintery worst, even with hunters and foxes and magpies and crows, it is not dreadful, but beautiful. And death, Salten notes, is inevitable for all.

Even He.

In 1938, with Bambi: a Life in the Woods a proven international success, and the Disney film already in development, Salten was forced to flee from his home in Austria to the safety of neutral Switzerland, where he was able to see Disney’s animated version of his most famous novel. (He called it “Disney’s Bambi.”) He died there in 1945, before he could return home to his beloved forests in Austria, to spend quiet moments walking among the trees, looking for deer.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.

Intersting trivia, the English translation of the book was done by

Whittaker ‘pumpkin papers’ Chambers.

So, oes the mother die in this book, then?

I read this book as a kid before I ever saw the movie, and I always liked it better. You’re making me want to go re-read it; I don’t think I’ve read it since I was twelve or thirteen.

@JAWolf – And further interesting trivia: he did the translation during his Communist days. No wonder the Nazis hated the book – written by a Zionist, translated into English by a Communist. (Though I don’t actually know if the Nazis knew about the second part. They definitely knew about the first part.)

@Lisamarie – Almost everyone dies in this book! Well, that’s a slight exaggeration. BUT A LOT OF ANIMALS DIE IN THIS BOOK, so it feels that way.

That said, Bambi’s mother doesn’t exactly die “on screen.” We just get “Bambi never saw his mother again,” and given the death toll and the scene right before it I just leapt to certain conclusions.

@ContentedReader – I think the book is much better, on all levels, than the movie.

The Nazis didn’t like Salten because of he was Jewish- full stop. Zionism was a mere ‘bonus.’

Typo in the last sentence: “tress”.

So is the forest fire a Disney invention, then, for the sake of drama? It sounds like life in the book is rather more routine, on the whole.

@6 I want to say there is a fire in the novel as well, but it’s been so long since I read it, I can’t rightly recall. Fires aren’t unheard of for the new growth they promote, though.

Salten also wrote the fine sequel, Bambi’s Children. That book contributed an ongoing joke to my family’s conversations. There is an owl who, as the figure of wisdom, quotes conflicting proverbs. “Fools rush in where angels fear to tread; on the other hand, He who hesitates is lost.” “The burned child dreads the fire; on the other hand, The broken pitcher goes oftenest to the well.” “Haste makes waste; on the other hand, A stitch in time saves nine.” As kids we found that hi-larious.

Fires are mentioned, but the huge forest fire is a Disney invention.

That said, I wouldn’t call life in the book particularly routine – one strong theme of the book is the constant, constant change. Winter is hellish for everyone, with several animals dying of starvation (this later became one of the few effective bits of the film); deer and other animals find themselves collaborating with human hunters; the hunters keep coming back, and back, and that’s a constant threat. And the animals are killed by other animals. The death count in the book is considerably higher than the death count in the film.

Thanks for giving more background than I had known on one of my very favorite books.

Thank you for this great overview of the original Bambi (though I read it in the English translation). I read this many times as a child–and got the anti-hunting (or specifically anti-wasteful hunting) message clearly. Pertinently to this discussion, Bambi’s mother is killed by a hunter, i.e. Him. Disney makes humans not responsible with the more cinematic fire. Salten also shows us a dead human—the old stag shows him to Bambi, reinforcing the recognition that humans too are animals, not gods, and subject to death even if they are themselves dangerous. This makes me want to go back and re-read the book–it’s rather sexist by contemporary standards (the does are more prone to fear, more engaged with the fawns, more gossipy–the stags are solitary mostly, very noble, and very admired and strong and silent)–but it handles death beautifully–esp. in the mayflies and the leaves.