One of the benefits of working as a book publicist is that I get to spend time with a lot of talented authors. For a longtime science fiction and fantasy fan like me, getting the opportunity to rub elbows with some of the field’s best and brightest minds is almost payment enough for the work I do.

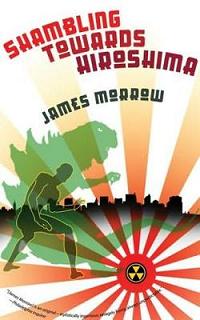

The most recent title I’ve been working with is the World War II era satire Shambling Towards Hiroshima. Written by James Morrow, Hiroshima is the story of B-Movie actor Syms Thorley, approached by the U.S. government to don a rubber monster suit and star in a film that simulates the destruction of a miniature Japan. Thorley’s handlers hope that the Japanese will be frightened into surrendering and spare the U.S. from having to unleash its real weapon: giant, fire-breathing mutant iguanas.

Morrow, the author of Towing Jehovah, has never been afraid to court controversy, but even I had more than a few questions about what brought him to address such a terrible episode in history and how he thought others might react to the novel. I thought that these questions might be best addressed in the medium of a short interview, which Morrow granted permission for me to reproduce here.

When did you start writing, and was there a particular thing in your life that pushed you toward this career?

I owe my career to my tenth-grade World Literature teacher, James Giordano, the enfant terrible of the Abington High School English Department, circa 1962. The syllabus was amazing: Kafka, Flaubert, Dostoyevsky, Camus, Voltaire, Sophocles, Ibsen, Dante, Shakespeare. From Mr. Giordano I learned that great literature is primarily about ideas. It cross-examines received wisdom and attempts to expose humankind’s fondness for self-delusion.

You’ve made a career out of using absurdist techniques to tackle serious topics. What is it about this method that appeals to you? Have you had any people become angry with you about works like Towing Jehovah? Are there any misconceptions people have had about you based solely on your work?

I think that the enigma of existence is so profound that we have to approach it through every available modality: science, philosophy, theology, literature, and, yes, absurdism. In this polyphonic conversation, no voice should be privileged on grounds of supposed supernatural authority. Indeed, when it comes to gaining insights into the mystery of it all, I would sooner listen to a satirist than a sacristan.

Perhaps the biggest misconception people take away from my work is that deep down, at some level, in the inner recesses of his manifestly troubled soul, James Morrow must really believe in God. But, for better or worse, I’m a die-hard skeptic and a shout-it-out atheist. The only Supreme Being I could imagine endorsing is the One who put me here to argue against His existence.

That said, let me hasten to add that I receive a fair amount of fan mail from believers, and this utterly delights me. Evidently churchgoers find in my fiction a curious affirmation of their own Judeo-Christian or mystical-pagan assumptions. I like to think this means I’m doing my job properly—taking worldviews from which I dissent and painting them sympathetically, so that all of us, theists and contrarians alike, can keep the great post-Enlightenment conversation going. Because if that conversation ever shuts down in the West, as it has apparently already shut down in the minds of Sarah Palin’s supporters, then we’d all better head for the hills.

I suspect the main reason Only Begotten Daughter and Towing Jehovah didn’t generate much hate mail is that fiction per se flies below the radar of the religious right. Today’s God-mongers know that novel-reading is a minority pursuit, so why should they waste their energies trying to thwart it? I’ve been called the Salman Rushdie of Christianity, a label I wear proudly, but here in the West nobody would bother to put a price on my head.

Tell me about Shambling Towards Hiroshima. How did you get the idea?

Godzilla is such a powerful archetype within our planet’s popular culture that even a degraded emanation like the 1998 Roland Emmerich retelling boasts a certain crude appeal. I came out of that lousy movie saying, “The myth still resonates. I want to do something with it.”

Coincidentally, I was reading Lifton and Mitchell’s Hiroshima in America, a revisionist critique of what might be called A-bomb Denial Syndrome. My first idea found Godzilla traveling to Washington in 1995 to inspect the controversial Enola Gay exhibition at the Smithsonian Institute. The great lizard is planning to incinerate D.C. unless the curators prove willing to acknowledge certain uncomfortable political, military, and human truths about Hiroshima.

Ultimately I decided that to use the historical facts of the Smithsonian exhibition in that fashion would entail far too much easy-do moralizing, far too much finger-wagging. So when Jacob Weisman invited me to contribute a novella to the Tachyon list, I rethought the whole premise from top to bottom, eventually hitting on the idea of a secret biological weapon developed by the Navy in tandem with the Army’s Manhattan Project. The Knickerbocker Project is a roaring success, bringing forth a generation of giant mutant amphibious bipedal fire-breathing iguanas.

Shambling

takes a very serious event in Japan’s history and juxtaposes it with one of the nation’s best-known pop culture exports: giant monster movies. How do you think that Japanese readers will respond?

I’m impressed with the way postwar Japanese society, with a few conspicuous exceptions, framed the Hiroshima and Nagasaki attacks: not as atrocious crimes committed by a heartless enemy, but as a terrible and universal human tragedy that must never happen again. You especially see this attitude in the original Godzilla movie, Gojira—not to be confused with the 1954 re-edit marketed to Western audiences. Rent the recent DVD restoration of Gojira, and you’ll see what I mean.

In that remarkable movie, the monster is clearly a personification of the atomic bomb, right down to his radioactive breath. Allegory can’t get much more explicit. The scenes depicting the aftermath of the monster’s attack on Tokyo include several wrenching moments set in hospital wards. With their graphic black-and-white realism, these images deliberately mirror documentary footage showing the effects of the atomic attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

So I would argue that in Shambling Towards Hiroshima I am continuing a tradition that the Japanese themselves started. Of course, I’ve added an element of satire and absurdity, which might offend some readers—but not mine.

Speaking of movies, I understand that you’re quite the cineaste. Are there any particular movies or actors that inspired you in the creation of Shambling? Syms Thorley seems like such a singular character, but I would guess that you’ve had a few real world models, right?

In Shambling I managed to combine two aspects of my sensibility that had never been united before: a moralist’s concern with thermonuclear weapons and a deep affection for old horror movies—the latter passion nurtured by the late Forry Ackerman’s magazine, Famous Monsters of Filmland. I’d written about atomic bombs before, in a novel called This Is the Way the World Ends. And I had managed to work a lot of monster-movie imagery into my recent novel The Philosopher’s Apprentice. But in Shambling these obsessions are fused, and that synergy totally galvanized me. Indeed, I managed to write the first draft in only about eight weeks.

The plot turns on the notion that the Knickerbocker Project scientists hope to exhibit their new biological weapon to a delegation of Emperor Hirohito’s advisors. By getting a dwarf form of the behemoth to destroy a miniature city in the presence of the Japanese ambassadors, the scientists believe they can leverage an unconditional surrender. But, alas, the dwarf behemoths all prove too docile, so the Navy has to hire a horror-movie actor, Syms Thorley, to don a lizard suit and wreck the model before the eyes of the visiting dignitaries.

Syms Thorley’s character combines elements of Boris Karloff, Peter Lorre, and Bela Lugosi—but he is primarily based on Lon Chaney, Jr., hence the cadences of his name. Like Chaney, Jr., Syms has a famous Hollywood father (an actor in Chaney, Jr.’s case, a screenwriter in Thorley’s case), and, like Chaney, Jr., Syms has played every sort of classic Hollywood monster (except for vampires, which his bubbe has forbidden as anti-Semitic).

I assume that you’re a history buff, or at least did a bit of reading into the actual lead-up to the Hiroshima bombing. How obligated did you feel to mirror in some way the real world event? Did our current wars in Iraq and Afghanistan figure into Shambling Towards Hiroshima? Would the book have been different without a current conflict like these?

My novella cleaves more closely to actual history than might be supposed at first blush. For example, there really was a minority sentiment among the creators of the A-bomb that the new weapon should be demonstrated to the Japanese, not simply visited upon them in a sneak attack. Assistant Secretary of War John J. McCloy was of this opinion, as was the physicist Leo Szilard, who’d drafted the letter, ostensibly written by Einstein, that convinced President Roosevelt to inaugurate the Manhattan Project.

Shambling was indeed composed in the shadow of two Middle Eastern wars, and I suppose that affected the narrative in subliminal ways. Anyone who’s read This Is the Way the World Ends knows that I’m a pacifist at heart—though I do allow that, under certain circumstances, soldiering is a necessary and honorable profession.

A hundred times more skepticism and reflection went into the decision to bomb Hiroshima than went into the decision to invade Iraq. Incurious George told us pesky citizens that it was all about “weapons of mass destruction”—a technology that, in my opinion, should really be called “satanic instruments of mass murder.” But Dubya couldn’t use that epithet, because then he’d be inadvertently critiquing our own fiendish arsenals.

Bush and Cheney were lying through their teeth, of course. I can’t say which notion is more troubling—the probability that they knew they were lying, or the possibility that they’d deluded themselves into thinking the WMDs really existed.

What do you hope that reader take away from Shambling Towards Hiroshima?

I’d like readers to consider that our affection for monster movies may come at a price. We should remain mindful of Susan Sontag’s point that the aesthetic pleasures of such films entail a certain “complicity with the abhorrent.” By all means, let’s continue to cultivate a taste for Godzilla, but it behooves us to remember what wanton destruction really means for its victims. Miraculously, the original Gojira manages to have it both ways. If the makers of that gritty little picture had been in charge of the Iraq War, I think it might have been prosecuted less cruelly.

I would also like the reader to sense that, when we ask whether Harry Truman should have dropped the bomb, we are perhaps addressing the wrong question. Rather, I think we should be asking two other questions. First, given the fear and remorse that the Hiroshima attack evidently instilled in Emperor Hirohito, was it truly necessary to hit Nagasaki immediately afterwards, as General Leslie Groves had arranged? And, second, how essential was it that the Pacific War end with minimal assistance from Stalin? (Without the A-bombs, the Japanese would most likely have surrendered as a function of massive Soviet involvement, a situation that Truman would not countenance, given his understandable desire to curtail Stalin’s postwar influence in the Far East.)

I’m not a trained historian, but I am pretty confident those are the relevant problems, and I like to think that Shambling Towards Hiroshima makes a small contribution to the debate.

Okay, I’m definitely intrigued. I’ll have to track down a copy.