Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s original stories—and some on his friends, too.

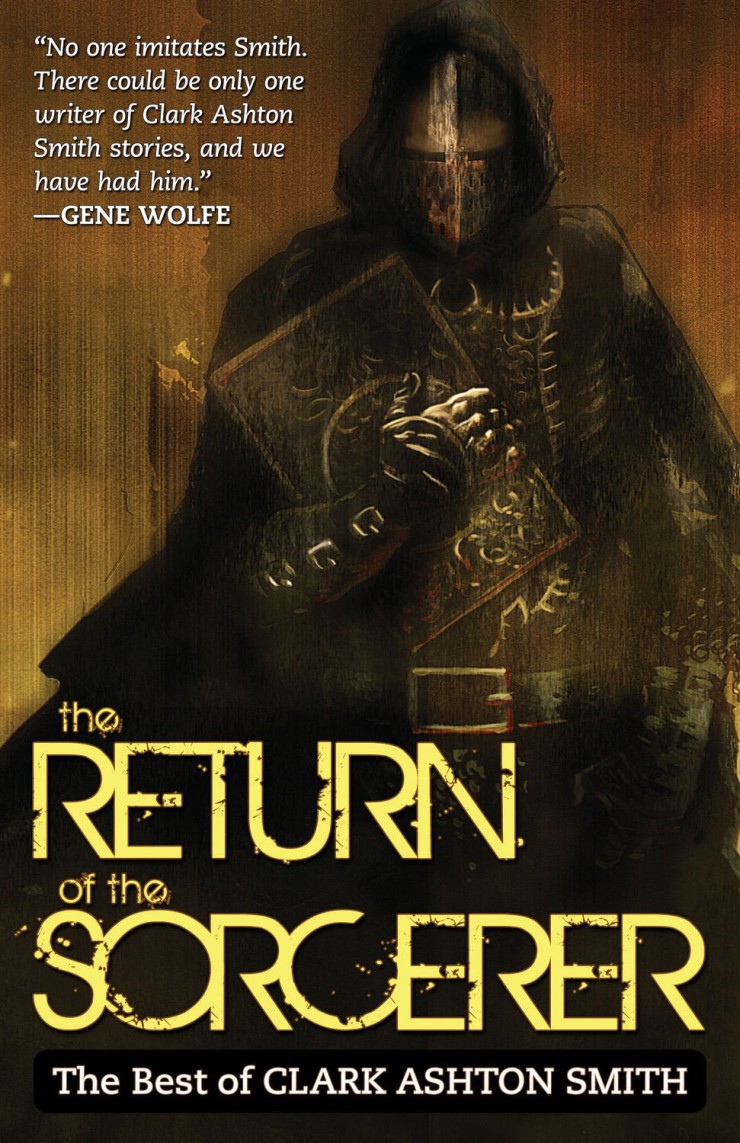

Today we’re looking at Clark Ashton Smith’s “The Return of the Sorcerer,” first published in the September 1931 issue of Strange Tales of Mystery and Terror. You can read it here.

Spoilers ahead.

“We returned to the study, and Carnby brought out from a locked drawer the volume of which he had spoken. It was enormously old, and was bound in ebony covers arabesqued with silver and set with darkly glowing garnets. When I opened the yellowing pages, I drew back with involuntary revulsion at the odor which arose from them — an odor that was more than suggestive of physical decay, as if the book had lain among corpses in some forgotten graveyard and had taken on the taint of dissolution. Carnby’s eyes were burning with a fevered light as he took the old manuscript from my hands and turned to a page near the middle. He indicated a certain passage with his lean forefinger.”

Summary

Our unemployed narrator answers John Carnby’s advertisement for a private secretary conversant in Arabic. He’s invited to Carnby’s house in suburban Oakland, which stands apart from its neighbors, surrounded by overgrown vegetation and mantled in unchecked ivy. Apart from the neglected landscaping the property strikes him as dismal, and his enthusiasm flags.

It flags further when he meets Carnby in his musty and shadowed library. The man is thin, bent, pale, with massive forehead and grizzled hair, but it’s not these marks of scholarship that trouble narrator. Carnby has a nerve-shattered air and feverish eyes, as if he’s broken his health with over-application. Even so, his broad shoulders and bold features speak of former strength.

Carnby’s most interested in narrator’s mastery of Arabic. He’s pleased when narrator agrees to reside with him, so as to be available at odd hours—pleased and even relieved, for he’s grown tired of his solitary life. His brother used to live with him and assist his studies, but he’s gone on a long trip.

Narrator immediately moves into a room unaired and dusty, but luxurious compared to his recent lodgings. Carnby shows him his study, which looks like a sorcerer’s den with its weird instruments, astrological charts, alchemical gear, and worm-eaten tomes. Carnby evidently sleeps in a curtained alcove. A locked cupboard’s set in the wall between skeletons human and ape. Normally narrator would’ve smiled at the decor; standing beside hag-ridden Carnby, he shudders.

Carnby explains he’s made a life-study of demonism and sorcery and is preparing a comprehensive monograph on the subject. Narrator will type and arrange his voluminous notes. He’ll also help with translations of the Necronomicon, in its original Arabic. Narrator’s impressed, for he’s heard the Arabic text was unprocurable. That evening he meets the fabled volume, richly bound in ebony and silver and garnets but redolent of decay. He deciphers a passage about how a sorcerer may will his dead body to animation, even if it’s been dismembered. He may thus perform any unfulfilled act, after which the reanimated corpse will relapse into clay.

Between the translation and a slithering in the hall outside, Carnby’s reduced to staring fear. The noise, he says, comes from one of the rats that infest the old house, for all his extermination efforts. He has narrator translate another passage, this one a ritual for exorcising the dead. Carnby studies it eagerly. He keeps the narrator until after midnight, but he seems more interested in company than work. His obvious apprehension infects narrator, but nothing perturbs him until he’s on his way down the lightless hall to his room. Some small, pale, unratlike creature leaps onto the stairs, then bumps down as if rolling. Narrator refrains from turning on the lights or pursuing the thing. He goes to bed in a “turmoil of unresolved doubt” but eventually sleeps.

All the next day Carnby’s busy in his study. Finally summoned there, narrator smells the smoke of Oriental spices, and sees that a rug’s been moved to hide a magic circle drawn on the floor. Whatever Carnby’s been up to, it’s left him much more confident. He sets narrator to typing notes, while he seems to await the result of his secret business.

Then they hear renewed slithering in the hall. Carnby’s confidence dissolves. It’s the rats, he again insists, but narrator opens the door to see severed hands scuttling like crabs. Other body parts are somehow mobile enough to take part in a charnel procession back to the stairs. Narrator retreats. Carnby locks the door. Then he sinks back into his chair and makes a stammering confession. His twin—Helman Carnby—was his fellow in exploring the occult and serving not only Satan but the Dark Ones who came before Satan. Helman was the greater sorcerer. Envious, Carnby killed him and cut up the corpse, burying the pieces in widely separated graves. Nevertheless, Helman has haunted and taunted him, hands creeping on the floor, limbs tripping him, bloody torso lying in wait. Helman doesn’t even need the head Carnby stashed in his locked cupboard, from which narrator’s heard knocking. First he’ll drive Carnby mad with his piecemeal stalking. Then he’ll reknit his sundered parts and slay Carnby as Carnby slew him. Alas, the ritual from the Necronomicon was Carnby’s last hope, and that hope’s failed!

Narrator ignores Carnby’s pleas he stay and hurriedly packs to leave the cursed house. He’s almost done when slow, mechanical footsteps sound on the stairs. They climb to the second floor and pace toward the study. Next comes a shattering of wood and Carnby’s scream, cut short. As if controlled by a volition stronger than his own, narrator is first paralyzed, then drawn to the study, whose door has been forced.

A shadow moves within, that of a naked man with a surgeon’s saw in his hand but no head on his neck. After a crash, the cupboard door whines open, and some heavy object thuds to the floor. There’s a silence as of “consummated Evil brooding over its unnamable triumph.” Then the shadow breaks apart. The saw clatters to the rug. Numerous separate parts follow it.

Still held by alien will, narrator is forced to enter the study and witness Helman’s revenge. Semi-decayed and fresh body parts are tumbled together on the floor. Facing them is a severed head whose exultant face bears a twin’s resemblance to John Carnby. The head’s malign expression fades, and its volition snaps. Released, narrator flees into the “outer darkness of the night.”

What’s Cyclopean: Clark Ashton Smith can’t quite compete with Lovecraft on the adjective front, but he gives it the old college try: Miasmal mystery. Recrudescence of dark ancestral fears. Malign mesmerism!

The Degenerate Dutch: Nada.

Mythos Making: Lovecraft’s most famous book plays a central role. But his mindless and malign pantheon are referred to only obliquely as “those who came before Satan.”

Libronomicon: Olaus Wormius’s Latin translation of the Necronomicon apparently leaves a few things out.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Reading the Necronomicon is unpleasant, but costs no sanity points. It’s killing your twin brother that leads to nervous disorders.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

The Necronomicon has gone through a lot of mutation over the years. Malign mutation, even. It starts as a book with a dreadful reputation—but the scariest thing it does is tell you that the thing you just experienced, the thing you hoped was a hallucination, was real. And explain exactly what was going on. And then you’re stuck, knowing that the creepy dude wasn’t just creepy, but a giant worm possessed by your witchy ancestors. Miskatonic keeps it under lock and key because it contains the most dangerous, terrifying thing you could possibly find in any library: the truth.

Later, we also learn that it includes instructions for dark magic. Edward Derby tells Upton that he knows what page holds the spell for forced body-switching. Presumably that means Ephraim has a copy around the house. Never mind that the volume at Miskatonic is supposed to be incredibly rare. This is the version we get in “Sorcerer” as well: the dread book of dark magics, with bonus unpalatable truth. And yet another copy, this time in the original Arabic. For a rare book, the Necronomicon sure does turn up a lot—sort of after the fashion of lawful good drow—and even more people seem to have read it.

By the time I first heard of it, the content of the Necronomicon was almost irrelevant. It was the book that would drive you mad simply with the reading, a brown note inherently magical and malignant in its own right (warning: TV Tropes link). Roll for sanity, just looking at the cover. I can’t decide which version is scarier—certainly I’d rather read the former… except that Lovecraft’s version implies an entire universe where the truth is too scary to face. The later version merely implies that Alhazred had it in for his readers.

And but so. “Sorcerer” itself is a fun little piece, notable mostly for its connection to the Mythos, and for the impressively high density of clichés. Why do so many wizards hang alligators from the rafters, anyway? Do enough spells call for reptile skin to make it worthwhile, like tacking up a braid of garlic in your kitchen?

Then there’s our narrator. At least he’s better motivated than many of Lovecraft’s, and notably has more reason to hang out with a bad idea boss than Herbert West’s companion. And enough sense to leave when the going gets eldritch. Still, when you discover that your employer is a dark wizard so evil that he murders other dark wizards from envy of their darkness, don’t stop to pack your valise.

The Carnby twins are as mustache-twirlingly villainous as one could desire. Brothers in Satan—small potatoes in the Mythos, probably dancing on mountain tops under Nyarlathotep’s protection—and lifelong rivals stuck in a house together. Being evil doesn’t help sibling rivalry any, so it’s no wonder one of them eventually goes after the other with an ax. And no wonder the other comes back, dismembered and decapitated, for his revenge. It’s an image both silly and scary, depending on whether you imagine watching it on screen, or actually being in that old house, hearing un-rat-like thumps from out in the hall—and knowing that if you look out your bedroom door, you won’t be able to un-see a thing you didn’t want to know possible.

Brr. Roll for sanity. Or alternatively, start snapping the theme from The Addams Family at the disembodied hand, and hope it’s a fan.

Anne’s Commentary

A suitable tale, this, to follow “Herbert West — Reanimator.” Once again the wronged dead will not lie still, even when they lie in scattered bits. If there’s anything worse than a faux-lively corpse, it’s the fragments of one, with a certain supreme nastiness appertaining to severed heads, whether carried in a box or shut up in a cupboard or balancing upright on whatever remains of their necks. And sneering. Sneering in triumph. Severed heads always win.

Compared to the serial grotesqueries of “Herbert West,” Smith’s tale is straightforward and spare. It uses many of Lovecraft’s standard tropes: the nameless narrator (here of the well-educated but hard-up subtype), the occult scholar with burning eyes syndrome (naughty subtype), the ominous house complete with wizard’s lair, the moldy tomes, the unspeakable practices, the mysterious noises blamed on rats (as if any self-respecting rat would hang out in an eldritch dump like this.) I take it that Smith’s Oakland is Oakland, California. The New England-birthed Mythos motored from coast to coast, presumably along Route 666! I find it a little hard to picture Lovecraftian horrors in the sunny state, unless maybe in Hollywood—say, a mansion like the one in which Gloria Swanson swans in Sunset Boulevard. But that’s my limitation. Why shouldn’t Dark Ones reign in California as well as Rhode Island and Massachusetts, since they’re cosmically omnipresent?

The reanimation itself is magical rather than pseudo-scientific, which allows for quicker exposition. If the Necronomicon says a sorcerer’s will is sufficient to bring him back from the grave (graves), however briefly, well, there you have it. Speaking of the Necronomicon. As we’ll see next week, Smith takes liberties with Lovecraft’s history of the ultimate tome. Not that they aren’t the sort of liberties we had to expect would occur as the Mythos began to seep out of extra-Lovecraftian pens. Not that they aren’t the sort of liberties we should welcome as a tasty expansion of canon. Lovecraft’s history states that the Arabic version of Alhazred’s magnum opus was lost as of 1228, when Olaus Wormius published his Latin translation of the Greek translation. Well, dark tomes do have a way of resurfacing, so why shouldn’t one surface in Oakland? Or end up in Oakland. I’m thinking that Helman Carnby got hold of it. Also that he excelled John in Arabic as well as in magical proficiency. Also that part of John’s envy and rage might have risen from what Helman withheld from the great book, most potent in this, its original language. It’s compelling as an object as well, with its ebony covers and silver inlays and garnet accents. The smell given off by its yellowing pages might repel the squeamish, but only further intrigue the occult connoisseur. Did the Carnbys’ copy pick up its charnel perfume by lying untold centuries in a tomb, clutched by a former owner? I like that thought. I also like the notion that our beloved Necronomicon—Book of Dead Names—might give off a spiritual miasma by its very preternatural nature. Or both. Why not both?

Smith does well to keep his timeline short, only a couple of days. Narrator couldn’t be expected to overlook mobile body parts for much longer. Besides, Carnby only needs him long enough to translate those two bits of Necronomicon pertinent to his immediate situation. Brevity keeps the atmospherics fresh, the ambulatory corpse-bits from getting comical through familiarity. We wouldn’t want the creeping hands to lose their horror, to become as cozy as Thing of Addams Family fame, now would we?

Last thought: I wonder why the ritual fails John Carnby. It can’t be that the Necronomicon (Arabic version!) was wrong. It could be that narrator made a mistake in translation. Or that Carnby directed him to the wrong ritual for exorcism of the dead. There have to be lots of those rituals, each with its special efficacy and purpose. Or Carnby, not the hottest sorcerer, might just have done the ritual wrong. Oops. Too bad. You should have drawn the REVERSED pentagram, not the UPRIGHT one, stupid. And you pronounced half the Dark Ones’ names wrong.

How Helman would have smirked in his cupboard, listening to bro’s bumblings. Yeah, Mom always liked Helman best, and for good reason.

PS: Quick safety tip for reanimators and murderous siblings of the wizardly persuasion, one Dr. West did use when possible: Don’t bury your subjects. Incinerate them! Maybe then scatter the ashes in the ocean! Though, who knows. Maybe Helman Carnby was so very willful, he’d have come back as an ash-cloud. An ash-cloud including the fish that had eaten some of his sunken fragments! There’s a scary image, now.

Next week, join us for the Miskatonic Valley Literary Festival, featuring “The History of the Necronomicon” and “The Book”.

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian novelette “The Litany of Earth” is available on Tor.com, along with the more recent but distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land and “The Deepest Rift.” Her work has also appeared at Strange Horizons and Analog. She can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal. She lives in a large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com, and her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen. The second in the Redemption’s Heir series, Fathomless, will be published in October 2015. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.