When the topic of the best 16-bit Japanese role-playing games comes up, most people think of the Squaresoft games like Final Fantasy, Chrono Trigger, and Secret of Mana. But my favorite 16-bit JRPG was a game developed by Sega for the Genesis called Phantasy Star II—one of the first JRPGs to take place entirely in a science fiction setting. The quest spanned two planets, had a cast of eight characters, and featured dramatic twists that made for some dark commentary on human nature. It also set the stage for titles like Xenogears and Star Ocean with its futuristic take on JRPGs, rather than the fantasy background almost all had before then. I’ll delve into what makes Phantasy Star II so special, starting with one of the first utopias in gaming.

The Phantasy in Star

Dystopias get featured a whole lot across the various mediums, but utopias are a rarer breed. Phantasy Star II starts you off in a utopia that seems pretty awesome on the surface. The geological implications of the world have a stronger impact if you played the first Phantasy Star and visited Motavia which was previously a desert planet. Think Dune, complete with giant sandworms, and you’ll have a good idea of what it used to be like. A thousand years later, Motavia has transformed into a paradise. Many of the citizens you meet in the capital, Paseo, don’t work, and instead lounge about in luxury. Everything is provided by an AI system similar to a Culture Mind (a la Iain M. Banks) called Mother Brain. There’s a techno-futuristic look to the townspeople with their varied hair colors and the art deco fashion styles. There’s also a uniformity in their appearance which I now realize was the result of limited memory space, but originally attributed to the guided cultural conformity of a planned society.

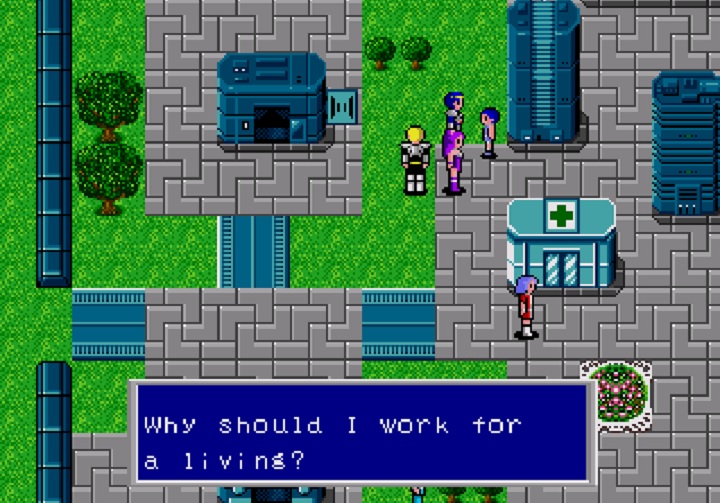

The worldbuilding in Phantasy Star II is fantastic, probably the best in any 16-bit era game—it isn’t shoved down your throat, but naturally expressed through the environment. There is limited exposition, but it’s integrated almost seamlessly into the game mechanics. Your “save states” are actually data storage areas where you can store memories, similar to the way the Culture downloads your brain. If you die, you’re not miraculously resurrected, but rather cloned by an eerie Joker-esque surgeon at the clone labs. Weapons are high tech and include salesmen who look like punk rockers. The available equipment ranges from guns to slicers and even the health potions have techy names like monomate, dimate, and trimate. The weather is perfectly regulated by the Climatrol. The biosystem lab grows creatures to balance the biomes of the world. The music is upbeat and super catchy, representing the optimism that pervades. The people are carefree and indifferent to the woes of the world. “Why should I work for a living?” asks one kid. Another says, “My dad is just goofing off everyday. He says he can live without working.”

When tragedy actually strikes and monsters run rampant, the citizens are shell-shocked, not sure what they should do. Part of why the story works so well is because the social structure feels organic with each element propping up the utopian vision of the future. You, as an agent of the government, are fighting to protect this seeming perfection.

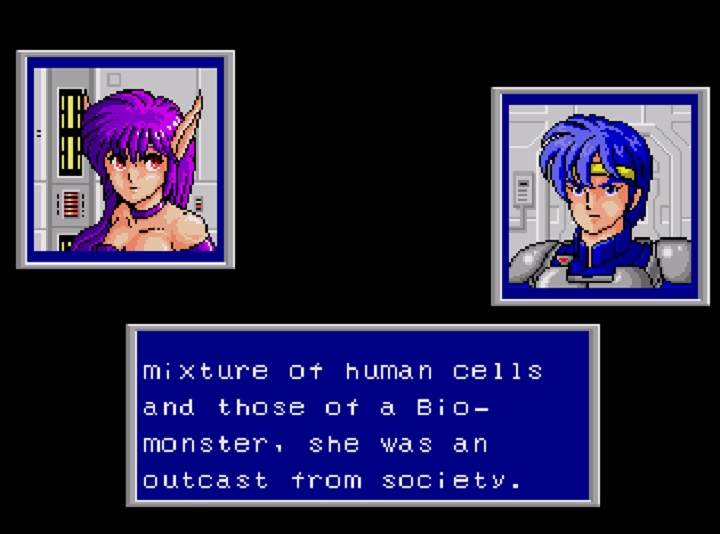

Rolf is the main protagonist, an orphan whose prowess with the sword garnered the attention of the government. He’s haunted by nightmares involving the heroine of the first Phantasy Star, all presented in gorgeous anime fashion. Your first companion, Nei, is a half-biomonster, half-human hybrid who was also orphaned and forms a sibling-like relationship with Rolf. Assembling a crew of companions that each have their own troubled past (which is actually explored in a visual novel based on the game), you’re given the task of finding out what’s gone wrong with Mother Brain. For some unexplained reason, the biosystem is generating vicious monsters rather than the creatures that should be supporting the world. The problems of the utopia aren’t necessarily endemic to the system, but rather, in the corruption of the central computer.

Phantasy Star II was massive, an interplanetary conflict that made me feel like I was only a small cog in a grander machine. For most of the story, you’re not actually able to alter the main events in any way way. Rather, you focus on discovering what’s transpiring while doing your best just to survive. My characters were growing stronger and the world had its own rhythm; fight monsters, teleport to different cities, save my memories on a data storage unit, then wander the lush greenery of Motavia.

The first stretch of this narrative has always had particular significance for me. I was in my early teens when a friend’s older brother described the space odyssey to me. I was incredulous, having a hard time wrapping my head around the fact that this was actually a game. Until then, I hadn’t seen the Sega Genesis and the best RPGs I’d played were all on the NES with primitive 8-bit graphics and only the most basic of plots. What he was talking about seemed more like a movie or a science fiction novel. But he assured me it was real and when I got to actually play it, I was in total awe. It was better than I could have imagined.

“Mother Brain is essential to our life, but nobody knows who made Mother Brain or where it is,” someone points out to you. I had no idea who the actual developers behind Phantasy Star II were, but the game quickly became essential to me.

Before Aeris/Aerith

The biggest leap 16-bit RPGs made from its predecessors was introducing gamers to characters that weren’t just blank avatars we could project ourselves onto, but individuals we could empathize with and root for. I think a big part of why so many gamers cherish those 16-bit RPGs was because it was the first time we experienced myths and heroes we cared about. At the same time, they were all our own. There’s almost a generational devotion to the games in the sense that it was something adults didn’t get and many times, dismissed entirely.

For many gamers, Aeris’s death in Final Fantasy VII represented the first moment in their personal monomyth where they “crossed the threshold.” Her death meant “leaving the known limits of his or her world and venturing into an unknown and dangerous realm where the rules and limits are not known.” In other words, the stakes were high when a character you got attached to could be killed. While Aeris’s demise shocked me, there were two moments in earlier JRPGs that shook me up even more. The first was when Kefka from FFVI pulled off his worldly apocalypse. The second was the death of Nei in Phantasy Star II. Context is really important here. Until then, most characters were archetypes representing fantasy tropes defined by class: warrior embodies strength, a black mage has offensive spells, while a white wizard is a healer, etc. The characters in Phantasy Star II were much more interesting, particularly Nei.

Nei was your best friend and an incredible warrior. One of the most useful features in the game is that characters use both their hands to attack. Bigger weapons like shotguns and swords require both hands, while smaller melee weapons allow dual attacks. Nei wields two claws and unleashes blow after blow on your enemies. For me, she always seemed to attack when I was weakest, dispatching foes in the nick of time. Battles were arduous—an aspect which I’ll get more into in the next section—but having Nei by your side felt essential, particularly as you dived into the mysteries of the biolab.

Investigating the biolab is one of the creepiest sections in the game. The monsters are brutal and attack in relentless waves. There’s stasis chambers everywhere containing the skeletal embryos of bizarre creatures. Chemicals are leaking over the ground. You have to drop into the basement to recover the recorder with the data you need. When you return it to HQ, you discover the whole system has inexplicably gone awry, punctuated by an energy leak at the climatrol system.

After a long quest involving underwater gum and a trek through the labyrinthine climatrol, you reach the center. Someone who looks almost identical to Nei is waiting there. She introduces herself as Neifirst and explains she is a failed bio-experiment who was targeted for extermination by the humans. When they failed to kill her, she vowed vengeance and wreaked havoc through the monsters at the biolab. Your party gets ready to fight her but she tells you if any harm comes to her, Nei will also die as their existence is conjoined. You have the option of avoiding battle if you wish, but the game won’t progress unless you do.

In the first part of the battle, Nei faces off in a direct combat with Neifirst. No matter how strong Nei is, Neifirst kills her. At that point, the whole sequence switches to an animated cutscene as Nei mutters her last words: “There’s no hope left for me. Please, Rolf [“Entr” in the version pictured] don’t let them ever repeat the mistake they made when they made me. I hope everyone on Algo can find happiness in their new life.” Then she dies.

I was sad, furious, and heart-broken.

Rolf and your party face off against Neifirst in a long battle. But even after you beat her, it doesn’t change Nei’s fate. It’s a bittersweet turn and in the last cutscene: “Rolf calls Nei’s name once again. But his plaintive cry merely echoes and re-echoes.” You rush to the cloning factory to try to bring Nei back, but it’s not possible. She’s permanently dead.

Games are our modern myths, more powerful than almost any other medium in the way it lets you experience the events directly. I’d never had a party member I actually cared about die permanently. There wasn’t any way I could change the outcome. I didn’t know game developers were allowed to do that. I was angry at the humans who created Neifirst, furious that I’d failed Nei, and confused now that the utopia was starting to implode after the climatrol system was destroyed. Had I made matters worse?

Hell is Random Battles

The biggest impediment to anyone interested in either playing Phantasy Star II or revisiting it is the endless grinding. The random combat is brutally repetitive and you will have to spend countless hours leveling up your characters just to make it through the next dungeon. I know that’s a staple of JRPGs, but Phantasy Star takes that to the umpteenth level, making old school gaming downright masochistic. You will die a lot. There was one cheat I utilized as a kid: if you bring up the dialogue box with every step you take, you can actually avoid random encounters. That comes in pretty nifty if you’ve run out of a telepipe or escapipe and barely have any HP left after a long grind session. Die, and it’s back to your last stored memory (I’ll be honest. I have two copies of the game, one in GBA form and the other in a PS2 Genesis Collection, so I didn’t feel bad loading this up on an emulator and using a PAR code to level up).

I loved the fact that the battles take place in a virtual battlefield with a Tron-like grid. You can program your attacks to automate them to a certain extent, even though you can micromanage each move if you choose. The animations are superb, both for the main characters as well as the strange bestiary of foes. The 3D backdrop of the battles plays well with the futuristic theme. The creature sound effects are some of the most unnerving ones around, giving each of them an alien vibe. In contrast, even the SNES Final Fantasy games were lacking in enemy and player combat animation, and very few had the type of sound effects Phantasy Star II did. Even its sequel, Phantasy Star III, took a big leap backwards in the battle system with almost no animation and static enemies, which made the grinding even more laborious.

One big gripe I have about the series as a whole is that their magic names are an almost indecipherable slew of techniques that go by names like Gra, Foi, and Zan. All these years later, even after looking them up, I can’t recall what each of them do. At least the ensuing effects were pretty.

Humans and Monsters

The best science fiction doesn’t just present a fascinating new world, but gives us glimpses into human nature from a different, somewhat subversive, perspective. As graphically advanced as the game was, none of it would have worked without the themes that propelled them. One theme that seems to come up repeatedly is best summed up by one of the townspeople: “What’s most frightening is humans, not monsters.”

In the case of Neifirst, ruthlessly hunted down by humans, it was their own actions that had caused so much mayhem and ultimately resulted in the destruction of life on their planet as they knew it. That one act of evil resulted in an imbalance of monsters that caused many civilians to turn to a life of banditry. You see its effects in one of the early cities you enter which has been been ransacked by the rogues, driven to desperation by the shift. They’ve kidnapped a man’s daughter and killed many in their way. Mother Brain seems like a welcome boon, a necessary presence to impose civil order.

Too bad you’ve disrupted the whole climatrol system and caused havoc on the planet. The government is after you. Even though the monsters are vanquished, robotic soldiers are everywhere in their attempt to subjugate your party. The environment is a mess and Mota seems like it will face an imminent catastrophe. When you talk with one of the villagers, wondering if they are panicked, concerned for their well-being and future, he instead happily says, “Now that those Biohazards are gone, we can live without working again.”

Oh brave new world that has such people in it.

Peter Tieryas is the author of United States of Japan (Angry Robot, 2016) and Bald New World (JHP Fiction, 2014). His work has appeared in Electric Literature, Kotaku, Tor.com, and ZYZZYVA. He dreams of utopias at @TieryasXu.