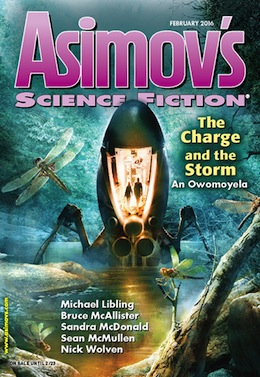

Welcome back to the Short Fiction Spotlight, a space for conversation about recent and not-so-recent short stories. In our last installment, I discussed the recent Queers Destroy Fantasy! special issue edited by Christopher Barzak and Liz Gorinsky—a decent mix of familiar and unfamiliar writers for me. This time around I’d like to look at the issue of Asimov’s that just arrived in my mailbox, February 2016, which fits a similar descriptive bill.

The February issue features short stories from Michael Libling, Bruce McAllister, Sarah Gallien, Sean McMullen, and Sandra McDonald, as well as two novelettes: one by Nick Wolven and one by An Owomoyela. This is Gallien’s first sf publication, though as her bio notes, she has been previously published in literary fiction circles; the others here aren’t new voices in the field, but also aren’t necessarily all folks I’ve read before.

The first story is Michael Libling’s “The Grocer’s Wife [Enhanced Transcription],” a cautionary tale told in excerpts as if from a transcript. Our protagonist works for a government agency that secretly infects targets’ brains with what appears to be early-onset Alzheimer’s; however, his recent target appears to be nothing but a grocer. When the protagonist realizes that the man has been targeted unfairly, he tries to go public with the story. Unsurprisingly, he is then himself targeted and no one believes him. The relationship the protagonist perceives himself to be developing with the target’s long-suffering wife as he tries to decide why she loves the grocer so much is the most interesting bit, but overall, the story reads a bit flat and predictable to me. The “twist” is far too obvious from the first, so it lacks the emotional impact it might otherwise have as we see the protagonist’s own girlfriend trying to deal with his development of the disorder at the close.

Then comes Bruce McAllister’s “Bringing Them Back,” a brief exploration of a world near extinction through the reflections of one man. The ecology of our planet has collapsed, mass extinctions wiping out the population, and he attempts to sketch and “bring back” the lost creatures one at a time—just for himself—including his wife and children, and finally himself. The concept is fairly well-trod, but the inclusion of the sketches and the idea of bringing the lost back through a catalogue is personal enough to add a touch of freshness. The prose could use a bit more punch and a bit less over-explication, though, for that emotional arc to have a better impact.

Sarah Gallien’s “In Equity” is developed from a novel excerpt, and it’s clear that that’s true from the structure of the piece itself: a section cut from larger cloth, showing us a significant moment without the build in either direction to make the arc feel complete. The descriptions here are good, though; the case worker’s teeth and shabby intensity are memorable, as is the house of the women who are looking to take in our young protagonist to send him off to a research school and take the reward fee for themselves. I think the work on class, identity, and the dystopian wealth-gap future could be more developed—and I assume would be in the novel-length version of the piece. This feels like a second chapter more than a short story, but I found it interesting enough to keep reading nonetheless.

Nick Wolven’s “Passion Summer” is about a more class-stratified future where people induce “passions” in themselves chemically; for kids, it’s a first-love choice of sorts, but adults often use it just to be able to make it through their daily work lives. Wolven develops a mother-son relationship that I thought was complex and engaging, while at the time giving a good amount of depth and time to the boy’s relationships with his young female friends. It’s very much a story about a kid with some typical daddy-issues realizing that he’s been looking at his parents’ failed relationship too simply, but that works here. The only thing I found frustrating was the intentional elision of the fact that our protagonist gets a passion for passions until almost the close of the story—it doesn’t add a damn thing to the emotional arc to make us wonder what he’s chosen, and it ultimately feels narratively artificial.

In Sean McMullen’s “Exceptional Forces,” a Russian scientist has discovered a colonizing alien world and a female assassin is sent after him to keep him from telling people. However, he and the assassin strike up a game-conversation and she ultimately decides to give up her whole life to be his “manager” of sorts and help him and the other few social savants take over the world and guide humanity into a greater future (where they can defend against those aliens). I found this, to be honest, tedious and a little offensive; the assassin’s character seems to be a caricature of a sexpot killer, and that trope in and of itself is enough to make me roll my eyes—more so when it isn’t handled with complexity.

Another rather short piece is Sandra McDonald’s “The Monster of 1928,”a Lovecraftian romp about a young person who identifies as a “fella” more than a young lady, living in the Everglades and encountering a monster out of myth. It’s also about class, race, and the cost of lives in the South as much as it is monsters—particularly when the hurricane comes through and nearly wipes out the protagonist’s family and community due to lack of warning or concern. I thought the casual allusions to historical record were the strongest part of the story, as well as the juxtaposition of actual monsters from the depths and the monstrous national white supremacist tendencies that lead to the cataclysm of the storm.

The stand-out piece of the issue is hands-down An Owomoyela’s “The Charge and the Storm.” The piece does solid work with issues of ethics, scarcity, and colonization. It’s a frame Owomoyela often works in, to good effect, and this story is no exception. Our protagonist, Petra, has a complicated relationship to the alien world she is living on and trying to belong to in a way that works for her and the human species at large. She’s also got a very complicated relationship to the other humans in the story due to her bridge-like role between the humans and the Su, who head the colony. Owomoyela’s prose is sparse where it needs to be and lush at the correct moments as well. I get a good sense of world, character, and concept alike; plus, I found myself actually engaged in the conflicts and their resolution. A worthwhile and thought-provoking story, overall.

As a whole, this was not one of the stronger issues of Asimov’s in recent memory. The Owomoyela story makes it worth picking up and the McDonald is reasonably engaging; the rest I found lackluster. There was a certain flatness of affect, here, and a lack of development in the stories in terms of character and emotional arc alike. I do hope that this is a fluke, and the stories will be back to usual in the next installment.

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic, and editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. She can be found on Twitter or her website.