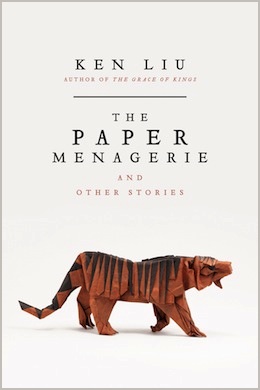

The first collection from Ken Liu, The Paper Menagerie and Other Stories, brings together fifteen stories of lengths ranging from brief short to novella. Liu’s work has been a staple in recent years in the sf world; he’s prolific as well as clever and striking in his creations. The titular piece of short fiction, “The Paper Menagerie,” was the first work of fiction to win the Nebula, Hugo, and World Fantasy Award in the same year—so, he’s no stranger to critical acclaim.

Liu notes in his introduction that he’s shifted more of his attention to long form fiction these days, but the impressive heft of this collection points to the amount of time he spent on short work over a relatively brief period of time. While fifteen stories sounds rather like an average amount for a first collection, The Paper Menagerie and Other Stories runs an upward of four-hundred pages (with relatively small type). There’s a lot here, to say the least.

As these are collected works, I’ve discussed several of them before in various short fiction columns—for example, the titular story “The Paper Menagerie,” as well as others like “The Litigation Master and the Monkey King” and “A Brief History of the Trans-Pacific Tunnel.” “Good Hunting” I’ll have to recuse myself on since I happened to be one of the editors who’d selected it back in my tenure at Strange Horizons. That still leaves the rest, though, and it’s a complex bunch of pieces.

SAGA Press, an SF imprint of Simon and Schuster that is just over two years old, has a mark to make in its design, presentation, and tone. In that department, there’s also the book as an art object to consider, and it is rather handsome and streamlined in its design: stark colors, a certain upmarket look that’s appealing and professional. It was pleasant to handle, pleasant to read.

The stories themselves are also of solid though somewhat variable quality. Liu’s aesthetic tendency is toward stories that revolve around an idea or concept—fairly traditional sf—and then explore the personal implications that the execution of the concept would have on individuals. Occasionally, this results in more of a pleasant thought-experiment than a gripping or memorable narrative; it’s a hard task to balance those tendencies against each other. When it works, though, it works astoundingly well (see “The Paper Menagerie,” which is utterly spectacular): Liu has a real talent for rendering families, domestic life, and human attachment of various sorts. When he’s working in those veins, there’s a vibrancy and color to the characters that’s hard to ignore. It brings to life the “what if” of the story’s given conceit and lets it breathe.

Some of the best examples of this are the longer stories, where Liu has more room to work. “All The Flavors: Tale of Guan Yu, the Chinese God of War, in America” is a novella, a bit shy of one-hundred pages in the volume, and it’s one of the ones I liked best. As a story, it mostly charts the integration of a small community of Chinese immigrant men into the mining town of Idaho City. It has a great deal of charm and movement in the narrative structure, and the tantalizing hint that the older man, Lao Guan (or “Logan”), is actually Guan Yu gives it a supernatural sort of significance. Lily, our young protagonist, and her family learn a great deal about their neighbors as the communities come together. It’s domestic, historical, and also somehow grand: the inclusion of folk stories and food and celebration as key divergence points makes this more than just a story about a handful of people learning to get along.

“The Man Who Ended History: A Documentary” is another long piece, and also perhaps the perfect one to close the volume. Dealing as it does with the brutal, terrible history of World War II-era conflict between Japan and China, centered around the horror of Pingfang and the “experiments” performed on Chinese prisoners there, this piece allows Liu to work at a scale both personal and political with issues of ethics, genocide, and the inestimable human potential for cruelty. However, he also approaches his characters and their struggle with a paradoxical gentleness: this is horror, but it is horror with context and a message about our tendencies as a species, across a broad spectrum. It’s a stunning piece, and absolutely a powerful last story to round out the retrospective of this collection.

I’d also note that part of the variation herein is likely a result of a great deal of productivity spread over a relatively short time frame: it’s impossible to hit it out of the park each time, and quantity is a different virtue. But even when Liu’s work doesn’t blow the reader out of the water, it’s well-done and entertaining. I rarely felt disappointed with the stories in this collection. While I sometimes also didn’t feel strongly about them, it nonetheless was a compelling experience in terms of prose. “The Perfect Match” is an example of one of the middling stories of the bunch: the plot is predictable and the exploration of corporate surveillance isn’t necessarily a fresh take, but the characters are interesting enough that their interaction gets the reader through. It doesn’t linger on the palate afterwards, for sure, but it’s decent.

Liu’s collection is a good purchase for a reader curious about the range—in several directions—he has as a short fiction writer; it’s also hefty and certainly delivers on reward for cost, given that expansiveness and inclusiveness. Four-hundred pages plus of short fiction takes some time to meander through, and I appreciated doing so. I also appreciated the juxtaposition of these stories and their ideas, these stories and their human narratives—Liu has a good hand with balancing the curious concept (what is your soul was an object outside of you?) and a living exploration of it (Amy, the girl whose soul wasn’t the cigarettes in the pack but the box they came in). It doesn’t always strike sparks, but it’s generally pleasant, and more than worth pursuing for the moments when it does. Those moments, hands-down, make this a strong collection.

The Paper Menagerie is available now from SAGA Press. An earlier version of this review noted that the early review copy did not contain the original publication history of individual stories, but this information does appear in the published collection. The post has been updated accordingly.

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic, and editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. She can be found on Twitter or her website.