What to make, in this day and age, of Clifford Simak, an SF writer born in a mold uncommon in this era, and uncommon even in his own? A midwesterner born and raised, living his life in rural Wisconsin and the modest metropolis of Minneapolis, Minnesota. That sort of environment gave him a midwestern, pastoral sensibility that infused all of his SF work, from Way Station to “The Big Front Yard,” both of which were Hugo winners and both merged the worlds of rural America with the alien and the strange. Simak’s fiction also featured and explored artificial intelligence, robots, the place of religion and faith, his love of dogs, and much more. There is a diversity of ideas and themes across his expansive oeuvre. It can be bewildering to find an entry point into the work of older writers, especially ones like Simak. Where to begin?

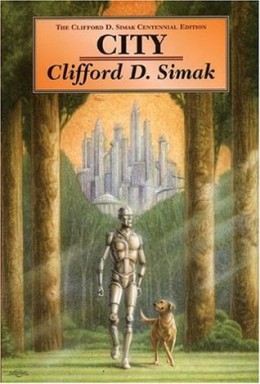

There is a simple, best place you can start though. A suite of stories that merges Simak’s love of dogs, his interest in rural settings and landscapes, use of religion and faith, and his interest in robots all in one package: City.

City is a fixup novel originally consisting of seven stories written between 1944 and 1951, and collected together in 1952. City charts the fall of Humanity’s (or the creature called “Man” in the stories) civilization, starting with his urban environment, and finally, of the fall of Humanity itself. As Humanity falls, so rises the successor to Man, the Dogs. As David Brin would later do to chimps and dolphins in his Uplift stories and novels, the story of the engineered rise of Dogs, and their supplanting of Man, is due to the agency of one family, the Websters. The growth and development of the Dogs is thanks to their agency, and the Dog’s continued growth is due to the help of Jenkins, the robot created as a butler for the Webster family who becomes a mentor to the Dogs and a through line character in the narrative.

When the stories were collected into City, Simak added interstitial material before each story in the form of looking back prologues from the point of view of the dog collecting the stories together into the collection. More than a mere metafictional technique to explain the existence of the collection within the world of the stories, the interstitial material comments on the stories and puts them into a context that the intended readers, the Dogs, can understand. This commentary and point of view gives the reader of the stories a perspective into what the Dog civilization has become, even as the stories themselves start long before the rise of that civilization. Too, this interstitial material provides an exterior counterpoint to the interior experience of what ultimately becomes a human apocalypse quite unlike most apocalypses in science fiction. We know, right from the first interstitial bit, that humans are long gone, and more than a little mythical. It is that context, with that inevitability that there is an end to Man, right at the beginning. It is not a nihilistic fatalism, but more in the sense that to everything there is granted a season, and the season of Humanity will inevitably come to a close.

Although the stories were written separately, together, with the binding material, they form a narrative, a future history of Humanity’s civilization from the 20th century and extending into the far future. Rather than using timelines and fixed dates for the stories as in the future histories of Robert Heinlein or Poul Anderson, the connections within are nebulous in terms of solid dates and intervals of time between them, expressing the march of history in terms of centuries and even thousands of years, as well as the Webster family, and Jenkins. This helps to reinforce the “tales collected and told” feel that the interstitial portions reinforce.

The first stories of the City cycle in many cases only touch tangentially, if at all, on the dogs that will inherit the earth. In “City,” the eponymous and first story, it is the end of the cities, the ruralization of America, the devolution of modern society that is Simak’s concern. Through “Huddling Place” and “Census,” Simak continues to build his world, his history, introducing the rise of the Dogs, the Mutants, and the changes in Human civilization after the dissolution of the cities. The stories focus on the generations of the Websters echoing forward through the years.

The heart of City, however the fulcrum point that all the stories revolve around is “Desertion,” originally published in 1944. Long before I ever knew that there were other stories in the sequence, I was struck by the power and pathos of the story. “Desertion” centers on an attempt to colonize Jupiter. By means of a device to convert a human into the best analogue on a particular planet, humans have been able to colonize the solar system. But when it comes to Jupiter, every man sent out in the form of a Loper, the dominant Jovian life form, has failed to return. It takes one man, and his faithful dog, to uncover the terrible truth. “Desertion” ends with an exchange of dialogue, four lines, that are for me the most potent ending in any SF story I have ever read.

After “Desertion,” the stories trend more and more into the lives of the Dogs who are inheriting the Earth, as Man retreats from the high point of his civilization. From “Paradise” through to “A Simple Solution,” Humanity retires to the fastness of Geneva, and in general give up the Earth to their inheritors. The dogs slowly grow and develop their own culture, their own mythology, their own civilization. And yet seemingly small events in the previous stories bear strange and unexpected consequences. As Humanity retreats and Dog advances, we see how Jenkins, and the remaining humans, do take pains to allow the Dog civilization to rise without the straitjacket and expectations and norms of the Human one they are supplanting. And we do quickly see that the world the Dogs build is a different world indeed, one with its own season of a rise and fall. By the end of “The Simple Way,” the full story of Humanity and the Dogs has been told. Or has it?

The last story in current editions of City, “Epilog” was written in 1973, more than two decades after “The Simple Way.” The title is evocative of the mood of the piece, as Jenkins, the one character that has persisted through the life of the Websters and the Dogs, faces the final end of the world—a wistful and elegiac look back at what they have done, and what they have left behind. It’s an intimate, tight story, a farewell to Jenkins, and to the world of the City cycle. It is hard to imagine the collection, frankly, without it. With an emphasis on the characters, the expanse of time, and the inevitable triumph, tragedy, and changes that Humanity and his successors will undergo, City remains as readable today to science fiction audiences as it did on its first publication. Combining all of the themes and ideas present in the various strands of Simak’s ideas, it is the first and best place for readers wanting to delve into the work of this seminal science fiction author.

An ex-pat New Yorker living in Minnesota, Paul Weimer has been reading sci-fi and fantasy for over 30 years. An avid and enthusiastic amateur photographer, blogger and podcaster, Paul primarily contributes to the Skiffy and Fanty Show as blogger and podcaster, and the SFF Audio podcast. If you’ve spent any time reading about SFF online, you’ve probably read one of his blog comments or tweets (he’s @PrinceJvstin).