Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

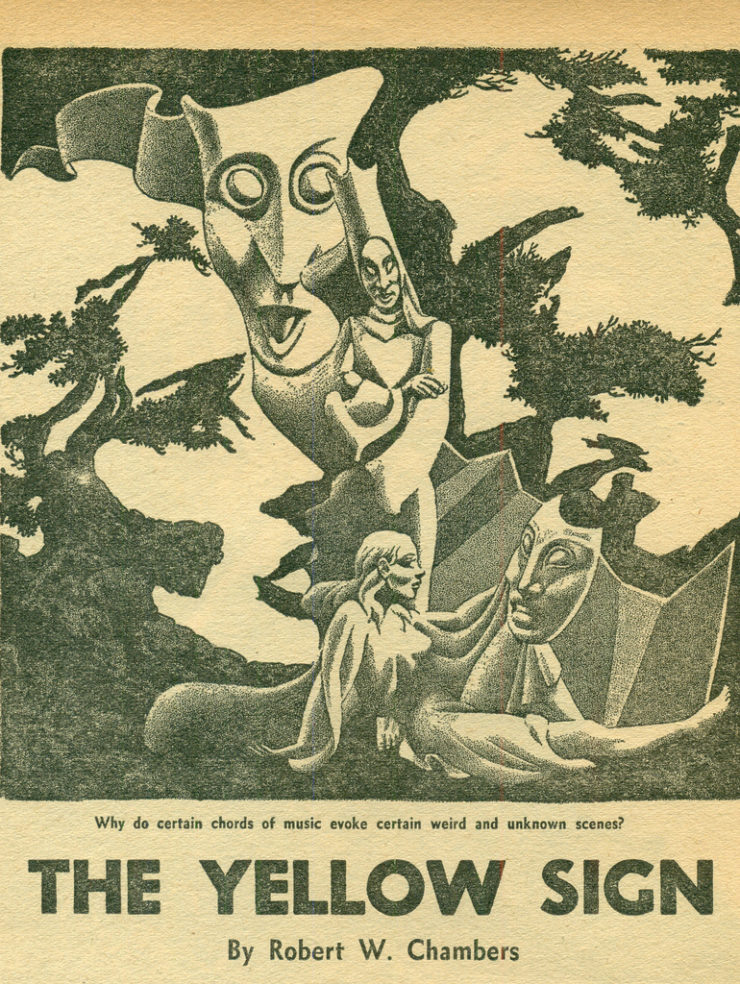

Today we’re looking at Robert W. Chambers’s “The Yellow Sign,” first published in his 1895 The King in Yellow collection. Spoilers ahead.

“Oh the sin of writing such words—words which are clear as crystal, limpid and musical as bubbling springs, words which sparkle and glow like the poisoned diamonds of the Medicis! Oh the wickedness, the hopeless damnation of a soul who could fascinate and paralyze human creatures with such words—words understood by the ignorant and wise alike, words which are more precious than jewels, more soothing than Heavenly music, more awful than death itself.”

Summary

New York, circa 1890, a decade about to get decidedly less gay (or maybe the same 1920s Chambers forecast in “The Repairer of Reputations“). Narrator Scott is a painter whose Washington Park studio neighbors a church. Lounging in a window one afternoon, he notices the church watchman standing in its courtyard. Idle curiosity becomes revulsion when the man looks up. His face looks like nothing more than a “plump white grave-worm.”

Scott seems to carry the impression back to his painting—under his brush, the nude study’s arm turns sallow, nothing like pretty Tessie, his model, who glows with health. He tries to correct the error, but instead spreads the gangrenous contagion. He’s not imagining it, for Tessie demands to know if her flesh really looks like green cheese. Scott hurls his brushes through the ruined canvas. With easy familiarity, Tessie chastises him. Everything went wrong, she says, when Scott saw the horrid man in the courtyard. The fellow reminds her of a dream she’s had several times, including the night before. In it, she’s impelled to her bedroom window to watch a hearse rumble down the midnight street. The driver looks up, face as white and soft as if he were long dead. Without seeing the occupant of the coffin, she knows it’s Scott, still alive.

Scott laughs off the macabre vision, even after Tessie claims the watchman’s face is that of her hearse driver. She’s been working too hard. Her nerves are upset.

Next morning Scott talks to Thomas, bellboy at his apartment house. Someone’s bought the church next door, but Thomas doesn’t know who. That “worm” of a watchman sits all night on the steps and stares at honest folk all “insultin’ like.” One night Thomas punched the watchman. His head was cold and mushy, and fending him off, Thomas pulled off one of his fingers. From his window, Scott verifies that the watchman’s missing a middle finger.

Tessie models for a new study, chattering about a young man she’s met. Scott ponders how he’s watched her grow from awkward child to exquisite woman, and how someone will carry her off as soon as she falls in love. Man of the world though he is, with no inclination to marry himself, he’s a Catholic who takes comfort in the forms of the church. Tessie’s Catholic, too. He hopes that will keep her safe from men like him.

At lunch, Scott tells Tessie about his own hearse dream, and yes, he does ride alive in the glass-topped coffin, and does see Tessie in her window, and he identifies the driver as the church watchman. He meant to illustrate the infectiousness of dreams, but Tessie breaks into sobs. She fears for Scott, and—she cares for him. Instead of deflecting her confession with laughter or fatherly advice, Scott kisses her. Tessie departed, he stews over the mistake. Oh well, he’ll keep their new relationship Platonic, and eventually Tessie will tire of it. That’s the best he can do since he lost a certain Sylvia in the Breton woods, and all the passion of his life with her.

Next morning, having passed the night with an actress, he returns home to overhear the watchman mumbling. He resists a furious urge to strike him. Later he’ll realize the man said, “Have you found the Yellow Sign?”

Scott starts the day’s session by giving Tessie a gold cross. She reciprocates with an onyx clasp inlaid with a curious symbol. She didn’t buy it—she found it last winter, the very day she first had the hearse dream. [RE: Y’all don’t want to know how easy these are to get online.] Next day Scott falls and sprains his wrists. Unable to paint, he irritably roams his studio and apartment under Tessie’s commiserating gaze. In the library he notices a strange book bound in snakeskin. Tessie reaches it down, and Scott sees with horror that it’s The King in Yellow, an infamous book he’s always refused to buy or even leaf through, given its terrible effect on readers. He commands Tessie to put it back, but she playfully runs off with it and hides. Half an hour later he finds her dazed in a storeroom, book open before her.

He carries her to the studio couch, where she lies unresponsive while he sits on the floor beside her—and reads The King in Yellow from cover to cover. Its words, “more precious than jewels, more soothing than music, more awful than death” overwhelm him. He and Tessie sit into the night discussing the King and the Pallid Mask, Hastur and Cassilda and the shores of Hali. Now that they know the onyx clasp bears the Yellow Sign, Tessie begs him to destroy it. He can’t, somehow. His communion with Tessie becomes telepathic, for they’ve both understood the mystery of the Hyades.

A hearse rattles up the street. Scott bolts his door, but its driver comes looking for the Yellow Sign. The bolts rot at his touch. He envelopes Scott in his “cold soft grasp.” Scott struggles, loses the clasp, takes a blow to the face. As he falls, he hears Tessie’s dying cry. He longs to follow her, for “the King in Yellow has opened his tattered mantle, and there was only God to cry to now.”

Scott writes this story on his deathbed. Soon he’ll confess to the waiting priest what he dares not write. Confession’s seal will keep the ravenous newspapers from learning more. They already know Tessie was found dead, himself dying, but not that the second corpse was a decomposed heap months dead.

Scott feels his life ebb. His last scrawl is “I wish the priest would—”

What’s Cyclopean: We hear much of the remarkable language of The King in Yellow, but never—thankfully—read any excerpts.

The Degenerate Dutch: Chambers’s watchman appears to have taken a page from Uncle Remus—but with an English immigrant rocking the heavy eye dialect. The probable satire is only a hair less sharp than in “Repairer of Reputations.”

Mythos Making: The King in Yellow was inspiration for the Necronomicon, which Lovecraft cited in turn as inspiration for Chambers’ creation of the fictional (?) play.

Libronomicon: You can get The King in Yellow bound in snakeskin. It’s probably snakeskin.

Madness Takes Its Toll: If The King in Yellow makes its way to your bookcase (mysteriously, possibly by drone delivery), you should not read it. Nor permit your guests to read it. Friends don’t let friends, etc.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Chambers messes with your head so wonderfully—perfect proto-Lovecraftian comfort food that leaves you wandering around asking what the hell just happened. Anyone who’s read The King in Yellow is, by definition, an unreliable narrator. And about to tell you something so horrific that you really wish you knew whether to trust it, but are kind of glad you don’t.

“Repairer of Reputations,” our previous Chambers read, takes place in 1920, unless it doesn’t, and involves a potential King-backed coup over a “utopian” (read “fascist”) United States, unless it doesn’t. “Yellow Sign” appeared in 1895, and seems to be contemporary, unless it isn’t. Our narrator is writing the whole thing down after reading the play, after all.

Though if enough people read the play, that might just result in the future portrayed in “Repairer.”

How is our narrator unreliable? Let me count the ways. From the start, he’s cagey about his past and self-contradictorily self-deprecating. He’s Catholic, gets comfort from confession, doesn’t like to hurt pretty women or leave them unmarriageable when he dumps them (all too easy in 1895). But he’s completely amoral, he assures us. Besides, his heart is with Sylvia, who is probably lost forever in the sunlit forests of Brittany. He’s unmarriageable, like a Trollopian heroine tainted by her first love. He lives in Hope. WTF happened in that backstory? How much of it is warped in his post-King retelling?

Then there’s the squishy watchman/hearse driver. An agent of the King? Entirely hallucinatory? He’s remarkably reminiscent of the folkloric tar baby. Joel Chandler Harris’s Uncle Remus collection came out in 1881, so an influence is very plausible. Remus’s bad rep post-dates Chambers—at the time it was one of the few windows a northern white dude was likely to have into Southern African American culture. But it certainly means something when Chambers chooses to translate the story from its original dialect into Cockney. Something sharp, I suspect.

The tar baby connection also provides hints about the watchman’s nature. Like the original, he has a knack for infuriating people by doing almost nothing. And like the original, acting on that anger is a bad, bad idea. It’s a trap! But set by whom? Is he, or his creator, responsible for the unsolicited book delivery? The purchase of the church? Tessie’s serendipitous jewelry acquisition? Another literary reference: Tessie plays the part of Eve here, persuaded to partake of forbidden knowledge, then sharing her Fall with the narrator. And so back to the narrator’s Catholicism, and his desire for confession.

I kind of love that the Fall doesn’t take the form of succumbing to the temptations of the flesh. That’s not even hinted at, even though it’d fit the narrator’s earlier protestations. Instead, they lose grace through… a late night book discussion. We’ve all been there, haven’t we? The joy of discovering someone who shares your fascination with Lovecraft, or Firefly, or Revolutionary Girl Utena… the strange synchronicity of opinions so in synch that they need not be spoken… the patina of debauchery imparted by sleep deprivation… There’s certainly nothing to compare with the intensity. It’s a wonder more stories don’t use it as metonymy for sin.

And then the ending. More WTF. Do we have murder by King’s agents? Murder-suicide? Multiple suicides? Has anyone actually died at all? We don’t even know whether to trust the narrator’s report of police reactions to the watchman’s body. If there is a body. If there was a watchman. Quis custodiet ipsos custodes? And who imagines them, trying to give form and face to an evil that might not, in fact, have either?

Anne’s Commentary

Here goes Yellow, once more associating its superficially cheery self with madness and decay. Mind-breaking wallpaper wasn’t enough for Yellow; no, in Chambers’ 1895 story collection, it clothes a terrible King and colors a Sign that exposes its owner (deliberate or accidental) to sinister influences and shattering knowledge. Yellow, how can I look at bananas and sunflowers the same way again?

The four dark fantasies in King in Yellow (“The Repairer of Reputations,” “The Mask,” “In the Court of the Dragon” and “The Yellow Sign”) were enough to earn Chambers very honorable mention in Supernatural Horror in Literature. Lovecraft felt they reached “notable heights of cosmic fear” and bemoaned the fact that Chambers later abandoned weird fiction for romance and historicals. Chambers could have been a contender, people. He could have been somebody, a “recognized master.” At least we have “The Yellow Sign,” which Lovecraft summarizes with zest and a certain odd omission or, shall we say, an obfuscation of a substantial subplot. That is, the GIRL.

Lovecraft tips his hand by sighing over Chambers’ “affected cultivation of the Gallic studio atmosphere made popular by [George] Du Maurier’s Trilby.” George was the grandfather of Daphne, and his Trilby was a turn-of-the-century blockbuster, selling 200,000 copies in the United States alone. Its depiction of bohemian Paris appealed to the romantic sensibility of a generation and urged young women to such depravities as smoking cigarettes, drinking wine, and reveling in unmarried independence. Just like Tessie in “The Yellow Sign.”

Tessie appears to have perturbed Lovecraft so much that she became literally unnamable. In his description of “Sign,” he thoroughly neuters her, or perhaps more accurately, neutralizes her presence as a sexual force. She’s known only as “another” who shares Scott’s hearse dream. Another what? Also, as “the sharer of his dream” and one of the “three forms” found dead or dying after the climax. I don’t know. Maybe Lovecraft was just worried about his word count and didn’t want to go into the whole Scott-Tessie relationship? Maybe he saw the romance as a disagreeable interruption of the shivery chills? Romance was certainly not his genre. We’ve already seen how little space the love stuff gets in his collaborations with Zealia Bishop and Hazel Heald; when it does break through, as in the truncated love-triangle of “Medusa’s Coil,” it seems a false note.

In Lovecraft’s solo work, falling in love is definitely no good thing. Look what happens to Marceline’s beaus, and Edward Derby, and Robert Suydam’s short-lived bride. Steady old couples like “Color Out of Space‘s” Gardners are all very well, though they too, um, fall apart in the end.

Best to leave the mushy stuff out whenever possible. [RE: Or at least avoid having pieces of it come off in your fist.] [AMP: Ew, ew, ew.]

Chambers doesn’t, though. That he would eventually make good money writing romance is presaged not only in the “non-weird” King in Yellow stories but by “Yellow Sign” itself. Scott’s evolving (and conflicted) connection to Tessie isn’t an afterthought; it shares about equal space with the scary elements. In fact it makes the scary elements scarier, the tragic outcome more poignant. In his own estimation, Scott’s kind of a jerk, the sort of man he hopes Tessie can escape. No marrying man, he’s taken advantage of women. He casually beds actresses. He’s annoyed when he doesn’t squelch Tessie’s love-confession instead of encouraging it with a kiss. He’s had his grand passion, still cultivates a flame for the mysterious Sylvia of the Breton forest. Yet he genuinely cares about Tessie, might have progressed beyond the Platonic relationship he intended for them, or, just as well, maintained that relationship with grace. Tessie is a charmer, after all. Audrey Hepburn could play her in the Ideally-Cast movie.

She’s also doomed, and why? Because she picks up a trinket in the street. A random event marks her with the Yellow Sign, and nothing’s random after that. She dreams the hearse. She dreams her beloved into a coffin, thus drawing him into the King’s web. She passes the Sign on to him, so of course the lethal book appears on Scott’s bookcase. Of course Tessie has to read it, and of course Scott does too, however forewarned.

Who buys the church, so the watchman can watch it? Who was he before he was dead and Death itself? What’s in that damn King in Yellow? Chambers dares let us decide and has the artistry to pull it off, so that even Howard overlooks the mushy stuff in the end and the King and Sign provoke our imaginations to this day. Why overlook the mushy stuff, though? Love and Death are an old, old couple, intricately knit one to the other, and picking at the stitches is one of the principal duties of art.

Next week, spend the end of your summer vacation in scenic Innsmouth: we’re reading Seanan McGuire’s “Down, Deep Down, Below the Waves.” You can, and should, find it in Aaron J. French’s The Gods of H.P. Lovecraft.

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Winter Tide, a novel continuing Aphra Marsh’s story from “Litany,” will be available from the Tor.com imprint on April 4, 2017. Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with the recently released sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.