Innumerable Voices is a monthly column profiling short fiction writers and exploring speculative fiction themes in their many permutations. The column will discuss stellar genre work from both fresh and established writers who don’t have short fiction collections or novel-length works, but who actively contribute to anthologies and magazines.Links to magazines and anthologies for each story are available as footnotes. Chances are I’ll discuss the stories at length and mild spoilers will be revealed.

In reading A. Merc Rustad’s catalog in preparation for writing this profile, I found myself reflecting on how I came to read speculative fiction and which characteristics fostered a full and unconditional adoration of the genre—one that has only found strength in subsequent years. Few other authors have proffered the exact conditions to revisit my initial, sublime surrender to SFF’s immeasurable potential and richness in possibility, which should already inform you about the powerful effect Rustad’s writing exerts.

I found myself both an adult, relishing in wickedness and tenderness alike, and a boy, as hungry and salivating at that first taste of wonder as any imaginative child on first introduction with science fiction and fantasy. Rustad takes the innate appeal of robots, labyrinths, monsters, and magic, and both elevates these familiar elements and offers critique when necessary in an honest, loving manner. In “Hero’s Choice”[1], they poke good-natured fun at the tired, genre-founding convention of “the Chosen One”, presenting an adoptive father-son relationship between the chosen one and the dark lord he’s supposed to slay. It’s both an overt parody that exaggerates the usual tropes and a clever subversion with honest moments of emotional connection between father and son. In a similar fashion, Rustad heightens the perils of enchanted labyrinths in “One With the Monsters”[2], but reinterprets the traditional roles of players and offers empathy in a place of desolation, while in “To the Monsters, With Love”[3], they invert the familiar narrative established in classic B-movies from the 1950s.

Another genre staple Rustad touches upon is portal fantasy in the charming “This Is Not a Wardrobe Door”[4], where they excel at crafting a believable child protagonist in Ellie, who’s been barred from returning to her magical land. Rustad writes their younger protagonists with honesty and generosity, whether it’s to capture a teen’s electrifying anger (“Where Monsters Dance”[5]), vulnerability and insecurity in (“Lonely Robot in a Rocket Ship in Space”[6]) or that purest form of innocence children possess when they simply don’t know of the horrible, cruel, senseless things that can happen in the world (“Goodnight, Raptor”[7]). For all its use of nanobots and a dinosaur, this last story is haunting due to its very young protagonist’s inability to grasp the situation, overlaid with the near-resignation of the raptor who comes to Benjamin’s aid.

Robots and AI in Rustad’s oeuvre are distinguished with empathy, a capacity for emotion, and rich inner lives—it’s a heartfelt reimagining of a concept in science fiction that often stands in for the absence of emotion and soul. These themes are best seen at work in two of my favorite stories, of those I encountered while preparing this profile—“The Android’s Prehistoric Menagerie”[8] and “Tomorrow When We See the Sun”[9]. Both stories are quintessential science fiction in the sense that they re-envision creation, stretch the possibility of reality, and are dense with story and creation, compressed worlds in one convenient bite. In the first, the android, Unit EX-702, is charged with saving and preserving “life and sapience” in the aftermath of a cataclysmic event. A straightforward narrative unfolds, but with each progressive scene Rustad questions the value we place on our human life as the only one worthy of sapience and challenges the reader to see intelligence in life forms we’d normally consider below us.

Unit EX-702 transforms its “menagerie” into a family unit and we witness yet again how the thoughtlessness of humans disregards the possibility of a life as equal and worthy as that of homo sapiens, building toward a truly magnificent finale. Beneath the obvious themes, Rustad touches upon atypical family models—specifically ones we choose and create for ourselves: a crucial survival tool for those of us who have been rejected by our own.

“Tomorrow When We See the Sun” follows the torturous path toward self-awareness and the concept of self through the experiences of a wraith, a type of organic drone, created for the sole purpose of serving as an executioner in the Courts of Tranquility under the Blue Sun Lord. Here Rustad performs triple duty—delivering lightning-quick, high-octane action that rivals the best that space opera has to offer; packing an abundance of worldbuilding imagery into a few choice words; weaving a complex and sincere story about claiming one’s humanity and achieving redemption through defiance and an act of renewing life. Identity and the power it holds function as a central binding agent for the story’s wealth as Mere, the wraith, upsets the order of things, challenges ultimate authority in the face of the godlike Sun Lords and in the process, rights a monstrous wrong: the erasure of the deads’ souls.

Identity as a theme, and its erasure, are a constant in Rustad’s stories again and again, which should not surprise anyone as Rustad themself is queer and non-binary. The freedom to live as one chooses, the sense of belonging we in the queer community seek out, and the debilitating effects of having our identities rejected and repressed are all things we have to live through on a daily basis, which is why stories like “Tomorrow When We See the Sun” and “Under Wine-Bright Seas”[10] affect me so much. In the latter, Rustad reveals the healing a prince undergoes as soon as a mysterious foreigner accepts him and liberates him from a life in which he’d have to cripple himself to fit the mold of a proper princess to satisfy his mother.

Acceptance is an act of liberation and empowerment further developed in “Iron Aria”[11]—a take on epic fantasy with strong elements of the single savior trope, but you can’t really mind when the writing is as gorgeous and evocative as this:

The mountain dreams pain. Cold iron vibrates purple-blue deep in the stone while tongues made from rot and rust bite and gnaw and hunger ever deeper.

The dam, buried like a tooth in the mountain’s narrow gums, holds back the great burgundy ocean. Otherwise it would pour into the Agate Pass valley and swallow up the mining town at the mountain’s toes.

[….]

The mountain is being devoured from the inside and it screams.

That which is deemed unconscious, unloving, is attributed its own secret sentience. The same extends to Kyru’s ability to speak to metal—a handy skill to have for a blacksmith in training. Suddenly, armor speaks its own silent language. This creates a double exposure of reality: one of metal laid over the one of flesh and bone. As the sole person privy to this hidden world, Kyru bridges the two and falls into a position to save his community, once he’s seen as a man and his abilities are believed by another like him—the Emerald Lion General, Tashavis.

If granting someone their identity is healing and empowering, then the opposite erodes and destroys the self, which is the case in the excellent “The Gentleman of Chaos”[12]. The hero in this story is imprisoned as a young girl, his death faked for the public and his identity used as a tool. This figurative death becomes literal in the philosophical sense as his name is taken and he is turned into the ideal bodyguard, until he’s just referred to as “She”—nothing here’s of his own choosing. In his line of duty, as imposed by his older brother, She’s stripped from his humanity bit by bit until She warps into a shell of a human. The brutality of it, of course, is layered—all told in Rustad’s preferred method of entwining two alternating storylines, which perfectly manipulates the reader’s emotions so that every nugget of information hits like a bullet. The end is dark as it is hopeless and satisfying.

A. Merc Rustad demonstrates enviable command over narrative, often opening with a grand statement that hooks you straight away; “The Android’s Prehistoric Menagerie” and “Tomorrow When We See the Sun” each have their first sentence double as a scene; “Thread”[13] opens with an arresting premise, which compels you to read. The storyline is then pulled taut from start to finish, as is the case in “Of Blessed Servitude”[14]—a wasteland futuristic western with a strong Mad Max vibe, where technology has twisted in such a way that it appears supernatural and the language strengthens this ambiguity, as witch-breath and sun demons share the same space with implants, scanners, and high-tech rifles. The story is rooted firmly in the here and now as two strangers cross paths under dire circumstances in the desert close to nightfall. Bishop is a take on the lone ranger type, who (metaphorically) rides into town and comes across Grace, the offering to the sunspawn crucified for loving another man—an explicit reminder of what happens to gay men in cultures where homophobia is acted upon. Effortlessly written violence ensues as the sunspawn arrives.

When they aren’t tightly coiling narrative tension, Rustad inhabits the story’s atmosphere fully, and in drawing out its weirdness finds ways to distill an entire character’s essence into a carefully selected scenes. This is the case with “To the Knife-Cold Stars”[15] (the sequel to “Of Blessed Servitude”) as it expands on this wasted, arid world with the introduction of the monstrous cityheart, which hungers for stimulation and novelty, and at the same time moves the reader with Grace’s loss, touched upon in the first story, now amplified in the wake of his self-sacrifice.

This is the efficient spell A. Merc Rustad crafts in their body of work: run wild with beloved concepts and images of speculative fiction until they turn into muscular, beastly things of grand proportions; readers try to follow along meticulously calculated trajectories, only to be then blindsided with deeper meaning and electrifying vulnerability. Speculative fiction has been hailed as literature without borders and without obstacles in front its authors. Rustad proves limits are optional. You come for the wonder and imagination, but stay for the heart.

Footnotes

[1] Serialized and collected in Silver Blade Magazine,

[2] Published in New Fables 2010.

[3] Published in Flash Fiction Online.

[4] Published in Fireside Fiction.

[5] Published in Inscription Magazine.

[6] Published in Cicada Magazine.

[7] Published in Daily Science Fiction.

[8] Published in Mothership Zeta, reprinted in Boing Boing.

[9] Published in Lightspeed.

[10] Published in Scigentasy.

[11] Available to read in Fireside Fiction.

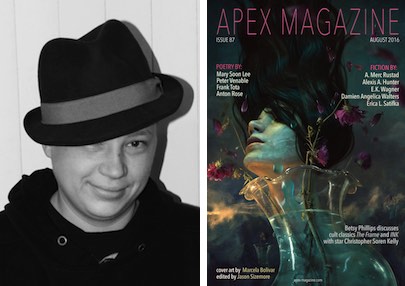

[12] Available to read in Apex Magazine.

[13] Available to read in Ideomancer.

[14] Available to read and listen to at Escape Pod.

[15] Available to read and listen to at Escape Pod.

Haralambi Markov is a Bulgarian critic, editor, and writer of things weird and fantastic. A Clarion 2014 graduate, he enjoys fairy tales, obscure folkloric monsters, and inventing death rituals (for his stories, not his neighbors…usually). He blogs at The Alternative Typewriter and tweets @HaralambiMarkov. His stories have appeared in The Weird Fiction Review, Electric Velocipede, Tor.com, Stories for Chip, The Apex Book of World SF and are slated to appear in Genius Loci, Uncanny and Upside Down: Inverted Tropes in Storytelling. He’s currently working on a novel.