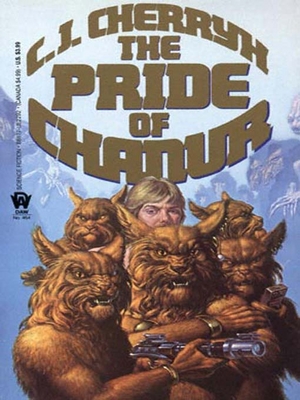

The Pride of Chanur (1981) is a standalone novel followed by a trilogy (Chanur’s Venture, The Kif Strike Back and Chanur’s Homecoming) and then another standalone volume, Chanur’s Legacy. If you view the trilogy as one book, and I certainly wouldn’t recommend starting those books without having all three of them right there, you can see it the whole series as a trilogy. The present way of publishing them in two volumes constituting The Pride of Chanur with the first half of the trilogy and then Homecoming with Legacy makes no sense as far as the story is concerned, though there may be useful marketing and bookbinding reasons for doing it that way.

This falls squarely in the middle of my very favourite subgenre of SF, the kind with aliens and spaceships. There’s a fairly standard way of writing a science fiction story in which one human is stranded amidst aliens, and it’s from the human point of view as the human learns the aliens. What Cherryh does in The Pride of Chanur is to write this backwards. She tells it from the alien point of view, and she does it brilliantly. There’s a Compact of different aliens—the pacifist stsho; the inquisitive mahendo’sat; the leonine hani; the piratical kif; and then the methane breathers who are really weird: the t’ca, whose messages are six part and can be read in any direction; the mysterious chi; and the knnn, who wail into their communications units and whose actions are quite incomprehensible. Pyandar Chanur is a hani captain, a trader, and she isn’t expecting an alien escaping the kif to run into her ship, bringing chaos in his wake to disrupt the whole Compact. I’d have liked this book from the human point of view, but from Pyanfar’s point of view, alien and comprehensible viewing human and other aliens, comprehensible and incomprehensible, it’s unbeatable.

There had been something loose about the station dock all morning, skulking in amongst the gantries and the lines and the canisters which were waiting to be moved, lurking wherever shadows fell among the rampway accesses of the many ships at dock at Meetpoint. It was pale, naked, starved-looking in what fleeting glimpse anyone on The Pride of Chanur had had of it. Evidently nobody had reported it to station authorities, nor did The Pride.

Cherryh always evokes rather than describes, and this first line is a really good example of that—it evokes the scene and draws you in. You want to know what the thing is—and of course it’s a human.

The thing people sometimes don’t like about these books is that they’re extremely complicated. The Pride of Chanur isn’t as bad as the trilogy for that. The Pride of Chanur is introducing the universe and the characters and the aliens and the spacestations, it moves fast and assumes you’re paying a lot of attention and never backs away from its point of view to explain what hani take for granted. I don’t find it hard to follow, but at this point I’ve read it a million times. It definitely is a book (and this goes double for the trilogy) where it makes more sense on a re-read where you understand what’s happening and know what’s coming. It’s definitely complicated, and it definitely makes no concessions, and it doesn’t give you time to catch your breath—but I remember loving it the first time I read it, and my son loved it when he was ten.

The Pride of Chanur is about the hani, mostly. The trilogy is about the kif, mostly—and kif really aren’t very nice. Legacy is mostly about stsho. The aliens are done very well, with all the complications and implications of what it would be really like to be like that. They’re definitely based on animal behaviour, and while this might make them less utterly imagined, it gets them into “stranger than you can imagine” territory. The hani ship crews are all female, because their males are pampered into being good for nothing but fighting each other. Pyanfar’s feelings on seeing her son and daughter overthrowing her husband and threatening her brother are not analogous to anything human. Cherryh has really thought through what it means to be an intelligent spacefaring lion, what it would feel like, and how you cope with things that are essentially intelligent spacefaring whales that breathe methane and have nothing in common with you at all.

This is a great story that begins a great voyage through alien territory.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published eight novels, most recently Half a Crown and Lifelode, and two poetry collections. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here regularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.