Promethean Brides

Poe was a child of the Romantics, and devoured works by Lord Byron, John Keats, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and Mary Shelley. Under these Romantic influences, Poe cultivated a natural philosophical appreciation for the metaphysical possibility and potential that scientific inquiry implied. However, distrusting any claim of “progress” that science offered to material man, he worried that it threatened the imagination, as the juvenilia “Sonnet—To Science” expressed: “Why preyest thou thus upon the poet’s heart, / Vulture, whose wings are dull realities?”

Despite his distrust of the Industrial Revolution, he could not help but study science and join his contemporaries in looking to it for answers. If science could put man on locomotives and harness electricity, who knew where man could go next—perhaps to the moon, or to a higher plane?

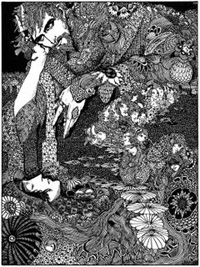

It is this unknown terrain that appealed to Poe, and became more pertinent as he grew older and watched more loved ones die. Within his forty years, Poe would witness the demise of his mother, foster mother, brother, and wife. Without religion, the uncertain hereafter gnawed at him and expressed itself as the overarching theme of his canon. While “Ligeia” used alchemy to show the full potential of the imagination, as well as perhaps a metaphor for equality among the sexes, its true hope was that love could be reunited and the Conqueror Worm overcome. However, Poe disbelieved mysticism, only utilizing it as a thought-experiment/literary device exploring what not even science could conquer: the afterlife. Poe, whether with feminist or masochistic intentions, used the feminine as the control group for various thought experiments. “Berenice” tested the faults of memory and objectification; “Ligeia” hypothesized the alchemical process; whereas “Morella” explores the metaphysical concepts of change and personal identity.

After Birth

“Morella” and “Ligeia” are similar tales. “Morella” can be seen as the prototype, or the mother of “Ligeia,” a more verbose and calculated tale than her predecessor. Their main difference culls upon how the two heroines escape death. Both are not only distinguished by their beauty but by their intellect, which is always more vast and perhaps terrifying to the narrator husband, who, in both tales, describes himself as resigning to their knowledge and leading an existence more akin to pupil than lover: “Morella’s erudition was profound .her powers of mind were gigantic. I felt this, and in many matters, became her pupil. I soon, however, found that she placed before me a number of those mystical writings which are usually considered the mere dross of the early German literature.”

While Ligeia obsessed over the philosopher’s stone and an alchemical marriage, Morella and her husband were more preoccupied with the individual: “ the notion of that identity which at death is or is not lost for ever—was to me, at all times, a consideration of intense interest; not more from the perplexing and exciting nature of its consequences, than from the marked and agitated manner in which Morella mentioned them.”

The narrator cites John Locke as a major influence. His views on identity held, according to Oxford’s Carsten Korfmacher “that personal identity is a matter of psychological continuity.” According to this view, “in order for a person X to survive a particular adventure, it is necessary and sufficient that there exists, at a time after the adventure, a person Y who psychologically evolved out of X.”1 Person Y would have overlapping connections of memory, habits, resemblance, and knowledge of X. Which leads to the quintessence of the issue: can one person become two? This is the question Morella dwells upon, and when she, like Ligeia, becomes stricken with an illness while also, unlike Ligeia, conceiving a child, she becomes mysteriously pensive. Morella comes to view motherhood as a path of continued existence: “The days have never been when thou couldst love me—but her whom in life thou didst abhor, in death thou shalt adore.”

The narrator cites John Locke as a major influence. His views on identity held, according to Oxford’s Carsten Korfmacher “that personal identity is a matter of psychological continuity.” According to this view, “in order for a person X to survive a particular adventure, it is necessary and sufficient that there exists, at a time after the adventure, a person Y who psychologically evolved out of X.”1 Person Y would have overlapping connections of memory, habits, resemblance, and knowledge of X. Which leads to the quintessence of the issue: can one person become two? This is the question Morella dwells upon, and when she, like Ligeia, becomes stricken with an illness while also, unlike Ligeia, conceiving a child, she becomes mysteriously pensive. Morella comes to view motherhood as a path of continued existence: “The days have never been when thou couldst love me—but her whom in life thou didst abhor, in death thou shalt adore.”

As her prophecy foretold, Morella expires as she gives birth to a daughter who becomes the narrator’s world. Even so, he avoids naming her, and as she begins to show only her mother’s traits, and none of her father’s, his love turns to dread:

And, hourly, grew darker these shadows of similitude, For that her smile was like her mother’s I could bear; but then I shuddered at its too perfect identity—that her eyes were like Morella’s I could endure; but then they too often looked down into the depths of my soul with Morella’s own intense and bewildering meaning . in the phrases and expressions of the dead on the lips of the loved and the living, I found food for consuming thought and horror—for a worm that would not die.

When the child turns ten, the narrator is coaxed into baptizing and naming her. The only moniker he can think of is the dead mother’s. When he speaks Morella out loud, the namesake becomes disturbed: “What more than fiend convulsed the features of my child, and overspread them with hues of death, as starting at that scarcely audible sound, she turned her glassy eyes from the earth to heaven, and, falling prostrate on the black slabs of our ancestral vault, responded—’I am here!’ ” The child dies.

When the narrator takes her to Morella’s tomb, he finds the mother’s body gone, of course implying that the child was the body of the mother, and the mother was the soul of the child, therefore reinforcing Locke’s view.

However, you cannot give Poe full philosophical credit. He does not provide an argument, but merely a thought experiment showing how the Lockean concept could apply. In fact, it could be argued that the Poe Girl stories provide a series of arguments on personal identity. In “Berenice” and “The Oval Portrait,” there is reinvention of the self as an object, and in “Ligeia” and “Morella” there is not only present the gaze-destructing feminism of women who refuse objecthood, but single-handedly uncover man’s “great secret.” While “Ligeia” could be read as the final draft of the Poe Girl stories, “Morella” initiates the metaphysical question of personal identity, body, and soul that are better expressed through the alchemical process in “Ligeia.”

There is one thing none of these stories thoroughly touch upon: a woman’s love. While matrimony bound all the characters discussed thus far, most of their marriages were out of convenience or weak wills. The relationships, perhaps excepting “Ligeia,” were minor details compared to the larger metaphysical hypotheses. Part IV will delve into the simple depths of a Poe Girl’s heart to see whether she can also forgive.

1

Korfmacher, Carsten. “Personal Identity”. The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 29 May 2006. Accessed 14 Sept. 2009. <http://www.iep.utm.edu/person-i/>.

S. J. Chambers has celebrated Edgar Allan Poe’s bicentennial in Strange Horizons, Fantasy, and The Baltimore Sun‘s Read Street blog. Other work has appeared in Bookslut, Mungbeing, and Yankee Pot Roast. She is an articles editor for Strange Horizons and was assistant editor for the charity anthology Last Drink Bird Head.