Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

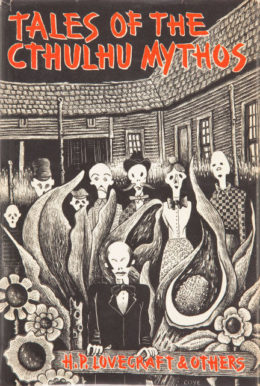

Today we’re looking at Colin Wilson’s “The Return of the Lloigor,” first published in August Derleth’s 1969 anthology, Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos. Spoilers ahead.

“The Lloigor, although infinitely more powerful than men, were also aware that optimism would be absurd in this universe… So they saw things clearly all the time, without he possibility of averting the mind from the truth, or forgetting.”

Summary

Paul Lang is a professor of English Literature at the University of Virginia and long-time editor of Poe Studies. At 72, he’s finally old enough to ignore the threat of colleagues’ dismissal; hence the story that follows.

For some years Lang has puzzled over the Voynich Manuscript, discovered in an Italian castle by rare book dealer Wilfred Voynich. A letter found with the book attributed it to 13th-century monk Roger Bacon. It’s written in apparent inscrutable cipher and includes astronomical diagrams and drawings of plants, cells and microbes that suggest microscope access centuries before Leewenhoeck. In 1921 Professor W. Romaine Newbold announced he’d deciphered passages, but later microscopic examination indicated the “cipher” was simply characters half-effaced by time.

Though Lang experiences a strange sense of “nastiness” on examining the Voynich Manuscript, he has photostats made, then high-definition photographs that help him see and transcribe the effaced characters whole. An Arab scholar identifies the script as a form of Arabic. Breakthrough made, Lang discovers the manuscript is actually transliterated Latin and Greek, easy to translate. It turns out to be “a fragment of a work that professes to be a complete scientific account of the universe, its origin, history, geography…mathematical structure and hidden depths.” From internal references, he learns the book’s real name is the Necronomicon.

Imagine his surprise when he learns that his newly-translated tome is referenced in Lovecraft’s fiction. He reads Lovecraft and recognizes ties to Arthur Machen’s work in mentions of the “Chian tongue,” and “Aklo letters” – also mentioned in the Voynich Manuscript! On vacation in his native England, he decides to visit Machen’s home territory in Wales. Caerleon, he’s sorry to see, is now a “dreary, modernized little town.” Its residents have forgotten their famous townsman and the legends that fueled his work, but Lang hears of Colonel Lionel Urquart, a “funny chap” steeped in local folklore. He wrangles an invitation from the curmudgeonly old fellow, author of books like The Mysteries of Mu.

The legendary continent sank in the Pacific, but Urquart insists its major relics lie in Wales and Providence, RI! He shows Lang a green stone inscribed with unknown characters and the image of a sea monster. That’s Ghatanothoa, Mu’s chief god. Lang must understand, though, that Mu’s rulers were invisible in their natural state, “vortices of power.” Alien to Earth, their instincts and desires were completely unlike ours, for they were fundamentally pessimistic. The Lloigor enslaved humans and punished rebellion with (to our minds) barbaric cruelty.

Lang’s impressed, even if he doesn’t quite get Urquart’s contention that it was the “optimism” of the young Earth’s subatomic energy processes that finally weakened the Lloigor and forced them deep underground and underwater. Occasionally they erupt in destructive spasms like the sinkings of Mu and Atlantis, for they hate their old slaves.

As evidence that the Lloigor persist in Wales, Urquart points Lang toward the high crime rate around Caerleon. Murder, rape and perversion flourish here, along with suicide and madness, as the Lloigor influence susceptible humans.

The local papers back Urquart up, as do Lang’s alarming encounters with a seductive hotel maid and a boy who seems to contemplate shoving him into a river. Meanwhile Urquart tumbles down cellar steps. The Lloigor, stronger under surface level, pushed him! As for Lang’s would-be attacker, that must have been Ben Chickno’s grandson. Chickno’s a “gypsy,” head of a half-idiot clan suspected of many sordid crimes. Avoid him like a “poison spider.”

Lang’s response to this warning is to take Ben Chickno to a pub and ply him with rum. The old man warns Lang to return to America. See, “they” aren’t interested in Lang, only the overly acute Urquart. If Urquart thinks they don’t have the power to harm him, he’s a fool. “These things aren’t out of a fairy story,” Chickno confides. “They’re not playing games,” but mean to come back and reclaim the Earth! Drunk, Chickno lapses into inarticulate—and perhaps alien—muttering.

Evidently Chickno himself is too talkative—overnight his clan encampment’s destroyed by an anomalous explosion, leaving nothing but scattered body parts and debris. Authorities pronounce it a detonation of nitroglycerin stockpiled for criminal purposes. But Urquart and Lang investigate the site and believe the Lloigor “punished” their unruly servants. Where did they get the energy? Lang thinks they drew it from inhabitants of a nearby village, who felt drained and flu-ish the next day.

After Lang and Urquart both experience a similar “draining,” they flee to London and continue to research the Lloigor together. News stories convince them the Lloigor are moving all over the world, causing explosions, earthquakes, homicidal madness and witchcraft outbreaks. They gather journalists, academics and other professionals to view their cautionary evidence, but earn only ridicule. Even mysteriously vanishing planes, gone for much longer than their crews experience, don’t sway the doubters.

The pair have better luck with American correspondence—a senator friend of Lang’s arranges a meeting with the Secretary of Defense. Lang and Urquart fly to Washington, but their plane disappears en route. Lang’s nephew concludes Lang’s truncated account with his own explanation: Urquart was a charlatan who tricked his naïve uncle into believing in the Lloigor. Either that, or his uncle was in on the elaborate hoax too. Because surely the Lloigor can’t be real. Right?

What’s Cyclopean: The word of the day is, sadly, “degenerate.”

The Degenerate Dutch: We are all descendants of the Lloigor’s slaves, but especially the Welsh. You can tell because of their high crime rate and surplus consonants. But scary-looking Romany, Polynesians, and people from not-Innsmouth are also likely to serve their ends.

Mythos Making: The Lloigor are elder gods by any other name. The Voynich Manuscript turns to be the Necronomicon by any other name. And Lovecraft and Machen knew what they were talking about…

Libronomicon: Along with the Necronomicon and Mysteries of Mu, this week’s shelf is full of everything from The Cipher of Roger Bacon to Lovecraft’s The Shuttered Room to Hitchcock’s Remarks Upon Alchemy.

Madness Takes Its Toll: The narrator is accused of being delusional, if he’s not merely a con man or practical joker.

Anne’s Commentary

I thought I’d read this story before, but I find I was confuddling Wilson’s Lloigor with Blackwood’s elementals in “The Willows” and Derleth’s Cthugha in “The Dweller in Darkness.” Oh well, Derleth did have a hand (along with coauthor Mark Schorer) in Lloigor’s creation: In “The Lair of the Star-Spawn” (1932), Lloigor is another of Shub-Niggurath’s kids, along with his twin obscenity Zhar. No Wilsonian energetics, this Lloigor and Zhar are prototypical tentacle-embellished Mythos monsters. Way back when the Welsh called their land Cymry, they called the land of the Britons Lloegyr, which looks a lot like Lloigor. Makes sense, since the Britons were foreigners, too, to the medieval Welsh. And there’s a Lloigor the Crazed in my favorite game, Diablo III, who’s related to Zhar the Mad in Diablo I! And “lloigor” has sometimes been used to refer to all the Great Old Ones, and even Outer God Yog-Sothoth.

Are we all confuddled yet?

Ahem and onward. I probably neglected to read “Return of the Lloigor” when I first devoured Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos as a teenager. Too much preliminary academic stuff, which put me off in those days. I’m old and wise now, so much more susceptible to the charms of “literary research stories” of the sort Lang attributes to his friend Irakli Andronikov. Google informs me that Andronikov (1908-1990) was a Russian literary historian, philologist and media personality. You know, a REAL person. So Wilson emulates Lovecraft in what Lang terms the fantasist’s method of “inserting actual historical fact in the middle of large areas of purely imaginary lore.”

“The Call of Cthulhu” was Lovecraft’s first great experiment in “fact insertion” and the larger strategy of using the painstaking research techniques of academic/scientist characters to temper his incredible material and thrill the reader with the sheer plausibility of it all. It’s appropriate, then, for Wilson to mirror “Call’s” structure in his tale of a professor plunging too deep into the TRUTH for his own good. A chance encounter tips professor off to potential worldview-shattering mystery (in Angell’s case, the wild dreams and bas relief of sculptor Wilson; in Lang’s case, Andronikov’s mention of the Voynich Manuscript.) Both professors get obsessed with their new interests, and increasingly alarmed by what they uncover. They amass historical data and employ news clipping services to gather relevant modern material. Alas, they attract the antipathy of cultists and even the cultists’ bosses, which means they must die, or maybe worse, disappear into torturous captivity.

A fundamental difference between the stories is what happens after the literary executors of the unlucky professors get hold of their notes. Angell’s executor is a grand-nephew, Lang’s a nephew, a nice parallel detail. But Francis Thurston comes to accept Angell’s conclusions about the clear and present danger of Cthulhu, while Julian Lang thinks his uncle was either the dupe of charlatan Urquart or Urquart’s accomplice in the Great Lloigor Hoax of 1968. Thurston opines that his great-uncle wouldn’t have published his findings, nor will Thurston do so. After all, it’s good that “we live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far.” Whereas Professor Lang and Urquart work hard to convince human authorities that the Lloigor are real, damn it, and COMING BACK. Crazy, Julian Lang thinks, but meh, he’ll go ahead and publish Uncle Paul’s story as the introduction to his already-planned book of selected cautionary clippings.

It’s interesting how Wilson borrows the basic premise of the Cthulhu Mythos without using Lovecraft’s fictive New England. Innsmouth is only Lovecraft’s invention, not a real place. On the tome side of things, the Necronomicon exists—Lang even has a fragment of it in the Voynich Manuscript—but where does the unabridged version live? There seems to be no more Arkham than there is Innsmouth, no Miskatonic University. What’s more, Lang and Urquart visit two other lairs of the infamous grimoire, the British Museum and the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris, without finding their Holy Grail. That Wilson mentions both libraries looks like a deliberate joke. Could he be implying that poor Lang and Urquart just didn’t know the secret password for Necronomicon access at these august institutions? How ironic.

Final thought: Wilson’s characters suppose that Lovecraft used the Rhode Island village of Cohasset as a model for Innsmouth. This isn’t one of his interpolated “real” facts, since as far as I know or can find with very moderate research, the only New England Cohasset’s in Massachusetts, and it’s uncertain that this once-dilapidated fishing village is the proto-Innsmouth, rather than say, Gloucester. However, Wilson’s right about the existence of Quonochontaug and Weekapaug, and really, how could he resist the you-couldn’t-make-it-up Rhode-Islandness of those majestic names? There’s the spice of authenticity for you!

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Despite occasional appearances, I really do love weird fiction. Make me shiver at the power of deep time, convincingly portray the terror of an impersonal universe, give me truly alien aliens with truly inhuman motives, and I’m yours. The problem is that this stuff is hard, and I’m really picky. Unimaginable depths of history that barely scratch the bottom of the British Empire, or the inane xenophobia of all-too-human stereotypes, kick me out of the cosmic and force me to entertain myself through sarcasm.

“Return of the Lloigor” is that rare story that manages to invoke both reactions. I spent the first several pages unable to get beyond the narrator’s excruciatingly bad research technique. But then he meets the Colonel, and all of a sudden we’re on a conspiracy-to-explain-everything rant worthy of Lovecraft on his most manic all-nighter, connecting Fortean phenomena, turn-of-the-century black magic cults, timelost airplanes, and… the Grand Canyon as obvious atomic crater? I’m sorry, have you ever seen a river? Then while I’m still recovering from the imaginative geography, the Colonel comes out with a truly stunning explanation of the Lloigor’s alien nature that evokes those rare shivers, and redeems the whole story through force of cool.

Or would, if he didn’t then insist that you can easily tell the descendants of slaves, aeons later, by their crime rates. It’s all a bit of a roller coaster ride.

First, the excruciating research technique. As last week, one bit of realism is the narrator’s fear of being scooped. And he’s right to fear it: the idea that no one has ever noticed that the Voynich Manuscript is simply faded medieval Arabic is… how shall I put this delicately… stupid. If I erased random bits of your familiar Latin alphabet, you would recognize them instantly. That’s how pattern recognition works. As an explanation for one of the most magnificent puzzles in literature, it leaves something to be desired. This isn’t the first time we’ve heard about the Manuscript in the reread, because it’s awesome. “Lloigor” turns down the weirdness volume well below the threshold of the real thing.

Then the glorious description of Lloigor psychology. It’s deceptively simple, and if you know how humans think, it’s terrifying: the Lloigor are realists. They engage in no self-deceptive biases, believe no stories about love or justice or morality. They look their own flaws square in the face. They accept the universe as chaotic and meaningless, and act accordingly.

My specialty as a research psychologist was wishful thinking, and I’ve come to appreciate its value. Self-deception motivates us to act—and push on till we succeed. It can make us more virtuous, and may be a necessary outgrowth of our ability see larger patterns in seemingly unrelated events. The same optimistic illusions can also completely screw us over, but it’s hard to imagine how we’d think without them. As an inconceivably inhuman mode of thinking, honest pessimism is mind-blowing.

Ah, but then we come to one of the less delightful aspects of humanity’s self-deception: we just love to find simplified ways of explaining other people. We particularly want our enemies to be easy to spot, and clearly much worse than we are. Degenerate, even. The Welsh and the Romany are both relatively common targets, and the quietly perverse and crime-ridden rural village a trope Lovecraft himself was all too fond of. Why should the Lloigor’s slaves so clearly fall into categories familiar to a casually bigoted author?

I’d rather just focus on the pessimistic god-things who can blow up your town by draining the energy and motivation of everyone nearby. It’s such a fascinating core idea that I’m tempted to overlook the story’s flaws, but some of them are about as big as the Grand Canyon.

Next week, not all songs in lost Carcosa die unheard. Join us for Damien Angelica Walters’s “Black Stars on Canvas, A Reproduction in Acrylic,” from Joseph Pulver’s Cassilda’s Song anthology.

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Winter Tide, a novel continuing Aphra Marsh’s story from “Litany,” will be available from the Tor.com imprint on April 4, 2017. Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with the recently released sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.