Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

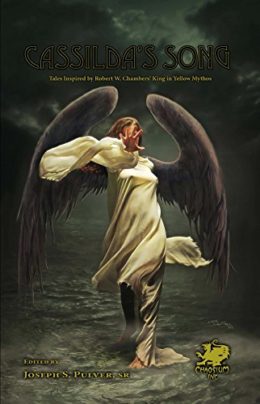

Today we’re looking at Damien Angelica Walters’s “Black Stars on Canvas, a Reproduction in Acrylic,” first published in Joseph S. Pulver, Senior’s 2015 anthology Cassilda’s Song. Spoilers ahead.

In the beginning was the word: six letters, two syllables. Unmask, the word like a totem on her tongue. She next ponders the word unmask. Unmasking is “peeling off a façade” to reveal reality. Doesn’t the artist do that by painting what’s real within her?

Summary

Painter Neveah has often heard rumors, whispers, stories of a patron who “changes the shape of one’s life” from unrecognized poverty to wealth—and more. If you can pass his audition, the Yellow King (obviously a pseudonym to protect his identity) can make a good artist great, a great artist a genius. He can grant perfection itself. Yeah, nice fairy tale, she thinks. Surely nothing more.

Then she receives a cryptic invitation: a card with a yellow symbol on one side, the single word unmask on the other. Though the yellow is bilious, sickly, “full of wrong,” she accepts the challenge of deciphering it. She’s heard this “King in Yellow” lives somewhere called Carcosa. Probably the name of his estate. She studies the yellow symbol, but finds she’s unable either to copy it or to reproduce the exact shade of its hideous color, though reproducing colors is one of her strengths.

Neveah starts painting and “slips into that curious fog of paint and brush, the emotions bubbling up and taking shape.” She produces a landscape of crumbling buildings, cobbled streets and hazy sky peopled with black stars and sun. That unreproducible yellow flashes in a corner of the canvas, despite the absence of yellow on her palette. She hears fabric on cobblestones, drops her brush, steps through a doorway that opens inside her. Silk brushes her skin. She has an “exquisite sensation of spiraling into perfection,” of floating weightless, “elsewhere.” The sound of a door slamming brings her back to her studio, shivering and clammy with sweat.

She tries to reopen the inner door by reproducing her original painting. No luck, she can’t get the reproductions exact enough. Was she only to get one chance with the King in Yellow? At a party, someone slips her a scrap of paper with a name and phone number on it. She calls Ivy Milland, who may have received the same royal invite as herself. Can Ivy give her any advice about passing the King’s “audition”? But Ivy only tells her to throw out the invitation and forget the whole matter.

Easily said. Impossible to do. Neveah realizes that the original painting needs not replication but expansion. Starting with the incomplete building at the edge of the original, she paints on in “a symphony of creation, of beginning.” The inner door opens. The bit of strange yellow in the first painting ripples, like the hem of a robe. Neveah slips back into the longed-for state of pleasure, perfection, transcendence, as if slipping back into a silken embrace. More “expansion” paintings reveal a second black sun, a dark lake. Then Ivy Milland asks to meet Neveah at a bar. She looks wasted, with dilated pupils like a drug addict’s. With startling anger, she demands to know if Neveah has found the doorway into Carcosa. Yes, Ivy answers herself, because his mark is in Neveah’s eye, a dark mote in her iris. Well, he can take that mark away, can take it all away, in an instant, discarding her as he’s discarded Ivy and leaving her with a “black hole” inside which nothing can ever fill again.

Neveah flees back to her studio. She keeps painting, producing eleven pictures of Carcosa that form a circle, complete. Standing in the center, she watches a flicker of yellow pass from canvas to canvas, as if inspecting them. It resolves into a robed and hooded figure. The inner door opens, but then slams shut with a force that drops Neveah to her knees in despair.

She smears paint over the Carcosa paintings and lapses into days of mindless drinking and sex. But “no narcotic, no orgasm, no fantasy, can fill the hollow [the King in Yellow]’s left behind.”

Eventually she revisits her studio and the smeared-over paintings. Moving them, she sees paint flake away to reveal the real Carcosa, still waiting for her. She scrapes at them, unpainting, unmasking. Carcosa expands to replace the studio, and she touches its bricks, walks barefoot on its cobbles, smells its lake. Silk rustles: The King reappears and stares at her with hidden eyes. He’s there for her, with the command to “unmask.”

Neveah understands at last. She strips, covers herself with paint, then scrapes it away from her skin, peeling back the false to bare “real black stars [taking] shape in her veins and twin suns [burning] in her eyes.” It feels “a little like dying, a little like lust and barbed wire entwined. She is everywhere and nowhere, everything and nothing, undone and remade and undone again.”

The King takes her hand as the last paint flakes from Neveah. Whether this is the right ending, she’s unsure, but it is an ending, and “all endings are also beginnings.”

What’s Cyclopean: The sign is “hideous, bilious yellow.” Apparently not a color you can find at your local paint store.

The Degenerate Dutch: Much degeneracy (or at least decadence), but no dismissive differentiation among human kinds this week.

Mythos Making: The Chambers references are sparse but central: Carcosa itself, and its infamous King moonlighting as artistic patron.

Libronomicon: No books, only paintings worthy to share a gallery with Pickman’s best work.

Madness Takes Its Toll: The King has unfortunate effects on those who fail his audition.

Anne’s Commentary

Did I tell you I’m easy prey for stories about artists, especially the haunted and/or tortured and/or doomed and/or transcendent variety? No? Well, then, just did. I love Richard Upton Pickman, for example, even though he’s so cheerful about his situation and leaves all the angst for his critics and secret-studio visitors. Thus it’s no surprise I love Damien Angelica Walter’s “Black Stars on Canvas.” The artist protagonist aside, I much enjoyed her debut novel (as Damien Walters Grintalis), Ink. That one involved a tattoo artist of diabolic genius and a man who learns it’s not at all a good idea to drink and then get one’s skin indelibly embellished.

It’s not really that cool to die for your art, kids. Or for someone else’s art. Or wait, is it?

What would Neveah say? That’s the question this story leaves me pondering. It’s also the question Robert Chambers leaves us concerning his King in Yellow. The painter protagonist of “Yellow Sign” loses his love interest to the mysterious monarch and ends up on his own deathbed after seeing the King’s “tattered mantle” open. Not so good for him, I guess. But is Tessie’s last cry one of terror or ecstasy? Dying and orgasm are often paired, metaphorically. Maybe in reality, for those with dangerous fetishes.

Like painting? The arts in general?

Walters writes with the richly sensuous imagery we can imagine Neveah creating via brush and pigments. As I’d love to see Pickman’s ghoul-portraits, I’d love to see her circular panorama of Carcosa, complete with the flitting yellow-clad figure she’s invited in to judge it. His raiment, if it’s indeed separate from his own physical/metaphysical substance, is described as the nastiest of yellows: bile, subcutaneous fat, pus (and not just any pus, gonorrhea discharge.) Eww, eww, eww. And yet, is this Kingly yellow nasty in Carcosa or sublime? Maybe it doesn’t register in full glory to our earthly eyes—like that Color Out of Space! Maybe it’s not “yellow” at all, hence Neveah’s difficulty in reproducing it. Maybe it’s only real when unmasked, under its own black suns.

When it’s true, real, art reveals the artist, or so Neveah believes. To whom does it reveal the artist, though? The door that opens for Neveah is inside herself, not in any other viewer. But as she discovers in the end, the physical object of her creation remains a shaky metaphor, not quite enough for the King in Yellow, the apparent avatar here of transcendent perfection. It’s not enough to reproduce Carcosa (her Carcosa) in acrylic. She must make herself the ultimate metaphor of unmasking, painting her own skin and then scraping off the disguise, the false color. Only then does Carcosa, black stars and twin suns, become part of Neveah. Or part of her again? Leaving her worthy of the King’s eternal embrace.

Transcendence, baby, like those last driving chords of Beethoven’s Ninth. Be embraced, you millions! This kiss is for the whole world!

Ahem, though. Beethoven’s transcendent kiss is a loving Father’s. Walter’s, the King’s, is a lover’s kiss, for sure. One of the nicest parts of this story is that intimation of the sexual and ecstatic woven through it. When Neveah’s “door” opens, she’s lost in timeless sensation. When it closes, she’s sweaty, she groans, but with satisfaction. Bereft of Carcosa and her King, she unsuccessfully seeks a similar high in boozy anonymous sex. It doesn’t work that way, girl. Not for a true artist like you. A dreamer, like Lovecraft’s many seekers, never content with the mundane.

And, definitely, this King in Yellow is anything but mundane. For good or ill, gotta like that in a guy. I wonder, though, how deep Neveah scrapes when she unmasks herself. Does she flay her own skin? Do black stars enter her veins because she’s cut them open? Is this ending her physical death? I kind of think so. That, or at least the death of her earthly sanity, her grip on this reality.

All endings are beginnings, however, and so death or madness are beginnings, too, the sort of doors into other realities for which doomed (or blessed?) dreamers are ever willing to pay a high price.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

We roll Chambers’ King in Yellow setting into Lovecraftiana by retconned honor, one of many authors whose influence on HP is obvious and explicit. And yet, it’s almost unique among those in that it has a mythology of its very own, compatible with the Mythos more by mood than by details. In some ways the two settings are complementary: Carcosa focused where the Mythos sprawls, tightly planned where the Mythos springs organically. And like the Mythos, it still horrifies and inspires decades later.

Chambers’s original stories, sweet and bitter as dark chocolate, are (if you’re me) shiver-inducing comfort food. But where modern Mythosian riffs are as common as drug store candy bars, finding sequels to that most scandalous play can be a challenge. So it took me about five minutes from learning of the existence of Cassilda’s Song—all Chambers riffs, all by women—to dropping hints to my blogging partner that I really, really wanted an excuse to pick it up. Fortunately Anne is understanding. And fortunately this new box of truffles promises some rich and intriguing flavors.

“Black Stars” isn’t clearly set in Chambers’s universe—or at least, we don’t hear anything about the infamous play. Instead, we’re reminded that writing is hardly the only art form that can induce madness. And the artist risks her own sanity to communicate that madness. Worse, the effect of failing to communicate it can be devastating. For some, the ultimate horror is when the words just sit there, or the paint is only paint.

Last week we talked about romantic poets, and their possible connection with eldritch abomination. This week the artistic decadence of those poets seduces the bastard offspring of “The Yellow Sign” and “Pickman’s Model.” No one lies debauched on a couch with their poet’s shirt half unbuttoned, but they’re probably doing it just off-screen, and there’s absinthe in the first paragraph.

The flavors meld just fine for most of the story. Inevitably, however, the conclusion has to be either poetic or cosmically horrible. Walters chooses poetry, at least if you think nirvana-ish oneness with the King in Yellow sounds like a pleasant fate. The story certainly treats it that way; a reader familiar with the King’s other hobbies can’t help feeling a little nervous.

Neveah’s frustrations ring true: overtly desirous of a patron who can overcome the “starving” part of her starving artistry, what she really wants is a patron who can bring her to her full potential. And more than that, to the experience of filling that potential. Plenty of artists would sell their souls to hit that elusive state of creative flow for just a little longer, just a little more consistently.

So is the audition test, or temptation? It’s not entirely clear how Ivy fails, or why painting over and then chipping off a masterpiece is the key to success. Is it the willingness to destroy, or understanding that the destruction is only a mask, that brings Neveah into the King’s approval? And is he a true patron, or does he have some ulterior motive? After all, her mysterious disappearance can only encourage other artists to keep flinging themselves on Carcosa’s altar. I can’t help wondering whether it’s the failures, and not the successes, that are the point of this strange exercise.

Perhaps those little calling cards aren’t so different from Chambers’s play, after all.

Next week, Fritz Lieber’s “Terror from the Depths” proves, yet again, that Miskatonic University is a terribly unsafe place to study the nature of dreams.

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Winter Tide, a novel continuing Aphra Marsh’s story from “Litany,” will be available from the Tor.com imprint on April 4, 2017. Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with the recently released sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.