The big literary book of the season, it seems, is the much-acclaimed Lincoln on the Bardo, by the much-acclaimed literary SF-nalist George Saunders. In this text, all of the action happens among the dead that accumulate around the cemetery where they are buried. These stubborn ghosts often refuse to acknowledge that they are even dead, referring to their coffins as their “sick-box” and await the time they heal and emerge from their “illness.”

This text has been widely reviewed (including at Tor.com) and the most striking element to me, when I read the text, was this seemingly unique way of approaching the narrative of life through the cemetery, and the ghosts, therein. The dead place resembles a neighborhood, and the ghosts who may not have known each other in life form friendships, talk to each other, tell each other the stories of their lives. The dead are more alive than when they were alive, for they are closer to their sense of self, separated from the realities of the world that bound them up into cages of pain and suffering and injustice. Their madness, if they are truly, deeply unhinged, is able to be more purely present in death than was permitted in life. Their love, if they are truly, deeply loving, is exacerbated by the absence of their beloveds—either friends or family. I was reminded, deeply, of a classic of American poetry, The Spoon River Anthology.

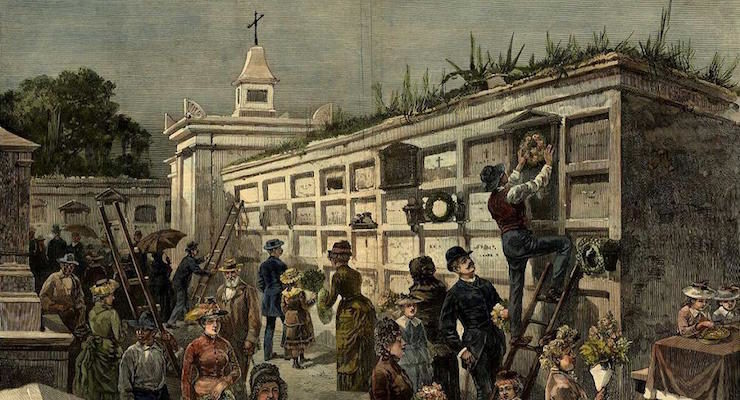

The way cultures imagine death says a great deal about the culture in life. There exists a consistent narrative that pops up in American media of a “little village of the dead” that allows individuals to continue conscious existence inside the walls of their cemetery, unable to impact the world at large directly, but speaking to the truth of their self, honed down to an essence, regardless. This conception has appeared over and over again in our books and stories. Here are just five examples, beginning at the edges of the idea, up to and including the ubiquitous midwestern bardo of the Spoon River.

Our Town by Thornton Wilder

A beloved play of cash-strapped theatre troops, one of the most heartbreaking moments comes in the third act when Emily Webb, whose wedding occurred just moments ago on the stage, is in the cemetery of Grover’s Corner, gazing back upon the living and upon life and trying to make sense of what she experienced, what it meant, and what to do with her consciousness now that she’s gone. She was the womanly emblem of young love, of living in the moment and experiencing all the joys and surprises of life. In death, she becomes the voice of the author, expressing the themes of the play from the perspective of the immutable endings, and all becoming a transient memory. Her acceptance of this state of being culminates in her return to the cemetery, lying down in her plot among the fellow Grover’s Corner residents at rest, quietly. It’s potentially a powerful and moving moment, depending on the quality of the performances, naturally. I am led to believe by my old English teachers that most theatre troupes are quite challenged to pull it off successfully without making the scene feel like a mere tearjerker.

The Graveyard Book by Neil Gaiman

Written by a British author who has lived in America for many years, and inspired by Rudyard Kipling’s famous Jungle Book, it is arguable that this is not an American book. But, it was written in America, and was very successful here. In the book, the dead are stuck in the moment, so to speak. They are done changing, done growing. They are still themselves, and they can make new friends out of newcomers as they like, but they are unchanging. A central theme of young adult literature, including The Jungle Book, involves learning from others, incorporating those new ideas into the self, and growing up. Bod’s adventure growing up among the dead is full of notions of life being growth, and death being still. The many ghosts that populate the cemetery will pick up their relationship with Bod as he reaches an age that is enjoyable to them and put it down when Bod moves on from that age. The various ghostly neighbors centered around the child and his main role model, vampire Silas—Mr. and Mrs. Owens, Mister Pennysworth, and Ms. Lupescu—form a cohesive village of decent folks, that together socialize and raise the lost boy, Bod. Except for Jack Frost and the terrible evil attempting to break through, it seems like an idyllic place for a child, in its way.

The Frighteners, directed by Peter Jackson

Preceding his later and superior work in The Lord of the Rings trilogy of films, The Frighteners was mostly forgettable and had some difficult to reconcile scenes and narrative decisions. However, one of the bright spots in the film comes when the psychic portrayed by Michael J. Fox walks through a cemetery, where ghosts hang out as if at a park. The guardian of the cemetery appears to defend the peace of the place in the form of the acclaimed character actor R. Lee Ermey! He steps out of his tomb as the classic Ermey-esque drill sergeant and takes command of the scene, upholding the natural order of everything, in which ghosts remain in the cemetery and psychics that upend the status quo are pushed and punched and shouted away. It paints a vivid portrait, indeed, of the notion that in death, we become our most authentic self. Each appearance of this ghostly drill sergeant is one of command, order, and vigorous defense of the “unit” of his fellow dead among the graves. It’s hard to imagine this spirit doing anything but shouting and marching and soldiering on, a reflection of the most authentic version of the man’s nature, stripping away pain and mortal necessities. His is an expression of brave love for his fellow men, his fellow dead, that would never be a whisper in the dark.

“Ancestor Money” by Maureen McHugh

In this breathtaking short story by a modern master of speculative fiction, our heroine lives in an afterlife of comfort and stasis, where her soul resides in a bardo state, not unlike George Saunders’ Buddhist reinvention of American history. It isn’t necessarily a cemetery, in my understanding of the text, but it can be read as such, with her burial separated in life and death from a husband she left behind at a young enough age for him to remarry and start another family. Instead resides with an uncle who was also present in her neighborhood of the afterlife, so to speak, along with some geese. In this spiritual state, she is bequeathed “Ancestor Money” by a descendent of hers whom she never knew that had gone on to live in China; the offering is made as part of a Chinese ceremony to honor ancestors. Her perfect, peaceful, little farm of the afterlife is upended as she leaves for China to acquire her gift. Having lived out an existence totally isolated from ideas of Buddhism, it upends her notion of the afterlife and seems to push her on to a new state of consciousness, where her remaining self is trying to reconcile all that she learned with all that she was. I mention this text, though it doesn’t contain the explicit cemetery village notion directly, because it echoes the bardo state of Saunders’ novel, as well as Our Town’s young Emily, taken so soon, attempting to reconcile what happened to her in life and in spirit. It is an artful approach to Emily’s same spiritual and practical dilemmas.

Spoon River Anthology, by Edgar Lee Masters

Ubiquitous among high school and junior high reading lists, Spoon River Anthology is a free verse poetry collection widely hailed as an American classic, and any vision of ghosts in a cemetery opining on their lives will be held up against it, just as any tale of chasing metaphorical white whales will be held up against Moby Dick. It is of great interest to genre readers, still, in that it is fundamentally a story of ghosts talking, and speaking of both injustice and the wider narrative of how their dreams brushed up against the weight of the real. For example, an aging married woman struggling to conceive arranges the adoption of her husband’s illegitimate child—born of what appears to be statutory rape—and raises that child up to be the mayor of the town. The real mother of the boy never forgets, stands in the crowd, and dreams of the day she can shout the true identity of her child to all with ears. Death releases them all of the obligation to mask what really happened. The hidden sins of the otherwise respectable town are on display, and the idyllic village of small town, midwestern America is revealed to be a place of misery, missed opportunities, cheats, liars, lovers, and a few decent men and women. It feels like what it might be like if brains could be uploaded to machines, and the soul of the machine abandons all the facades required by material folks who must move through society and make peace with it to survive. In death, there is no peace without truth. In the village of the dead, all come to the reader to tell the truth.

Joe M. McDermott is best known for the novels Last Dragon, Never Knew Another, and Maze. His work has appeared in Asimov’s, Analog, and Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet. His latest novel, The Fortress at the End of Time, is available from Tor.com Publishing. He holds an MFA from the University of Southern Maine’s Stonecoast Program. He lives in Texas.

Joe M. McDermott is best known for the novels Last Dragon, Never Knew Another, and Maze. His work has appeared in Asimov’s, Analog, and Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet. His latest novel, The Fortress at the End of Time, is available from Tor.com Publishing. He holds an MFA from the University of Southern Maine’s Stonecoast Program. He lives in Texas.