Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

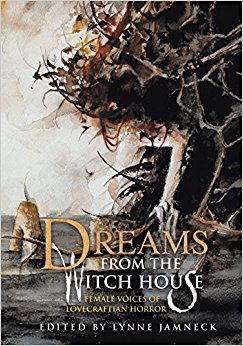

Today we’re looking at Sonya Taaffe’s “All Our Salt-Bottled Hearts,” first published in 2015 in Lynn Jamneck’s Dreams From the Witch House anthology. Trigger Warning for suicide attempts. Spoilers ahead.

“Under its dripping gloss of water, her skin was milky as old ice, so translucent across the promontories of cheekbone, collarbone, ribcage and hipbone that he wondered that she had not simply broken in his grasp, glassy as an abyssal fish.”

Summary

Anson Penders, a laid-off chemistry teacher, travels from Boston to Gloucester to “Samaritan” a suicidal stranger. His paramedic cousin Tony has rescued a girl trying to drown herself in the frigid February ocean; from certain anatomical features, like her webbed toes and emergent gills, he recognized her as another cousin and took her not to the hospital but to a “safe house” apartment. Anson arrives to find the girl, Gorgo Waite, crawling head-first into the bathtub. He drags her coughing and “lung-wracked” to safety. She is not grateful, and he soon realizes why. Her metamorphosis from air to water dweller is partial, permanently incomplete. Though the sea whispers her home both awake and dreaming, she can never claim the eternal life more fortunate children of Innsmouth share.

This is a predicament Anson can appreciate. Genetics have favored his siblings with an eventual “sea change,” while at thirty-eight he remains entirely a creature of the land. He’s watched his mother and other deep kin transition and slip beneath the waves. He’s listened to his brother and sister describing their vivid dreams of Y’ha-nthlei and of ocean-returned relatives—the kind of dreams he’s never had. Hell, he’s not even much of a swimmer. But he’s still better off than Gorgo, who is visibly stranded between two worlds, a freak. Who does dream of Y’ha-nthlei, which she’ll never visit in the flesh.

Over the course of the day Anson thinks of cousins he’s helped through the change. Gorgo confides that her father never finished his own change, dying of cancer first. He left her a journal, which may still be on the rocky beach where she left her duffel the night before. In need of fresh air, they leave the apartment to comb the beach for Gorgo’s things.

They don’t find them. As they search Anson remembers his cousin Isobel, a painter whose studio he emptied after her change. Among all her canvases, finished and unfinished, he found five small ones with bits of Innsmouth scripture scratched into their heavy impasto: come deep-spawning father come mother of endless waves come treasurer breaker of all our salt-bottled hearts.

He remembers that other cousins didn’t grieve for Isobel as he did. Isobel wasn’t dead to those who could dream their way to her, who would one day meet her again in Y’ha-nthlei.

Gorgo slips rocks into her pocket. “More weight,” she says. Anson suggests another form of suicide, entering the lottery of sea-blooded cousins, one of whom will be sacrificed at “the hinges of the year…for the mother and the father, for the sun and the moon, for the earth and the sea.” Not that he’s ever entered that lottery himself.

No, Gorgo says. If she wants the sea to have her blood, she’ll do it her way.

Anson thinks of the day when he’ll watch Tony go into the water. It’s harder to imagine life without his obnoxious cousin than without the boyfriend who’s reconciled him to life on land, but he knows it will happen. He’ll remain on the shore, as he does now, knowing that the sea gives back nothing that was not already the land’s.

Gorgo has wandered up the beach, “windblown at the waves’ edge with her hands full of salt and her eyes as huge and black as time.” Anson follows, “looking despite himself for drowned books, bottles, hearts rolling on the tide.”

What’s Cyclopean: “Imperishable,” in the English version of Innsmouth’s prayers, is “the unwieldy, inadequate translation of nineteenth-century hymnals for a word that shone like incorruptible gold in the devouring salt of the ocean, like the translated bodies of her children that time could not slow or slacken or kill.”

The Degenerate Dutch: Taaffe doesn’t mince words: the Innsmouth raid was “a tiny little genocide, right here in the heart of open-minded Massachusetts.”

Mythos Making: Diasporic Deep Ones are a dissertation waiting to happen.

Libronomicon: Gorgo’s father left her a book, the sort of mind-bending journal that often leads Lovecraftian protagonists to bad ends. It seems to have annoyed her mom.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Gorgo’s father doesn’t seem to have had great judgment, but also seems to have suffered from society’s failure to distinguish an inability to shut up about his amphibious ancestry from schizophrenia.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

I’ve read this story twice in the past week, after being blown away by the flashback sequence at Necronomicon, and I’m still not sure I have much coherent to say beyond “This is amazing.” Obviously “All Our Salt-Bottled Hearts” is up my alley to begin with–after the readings, Sonya pointed out that if we can get one more person to write about queer Jewish Deep Ones, we’ll have a genre. But it’s the language that ultimately gets to me, the way that every word builds world and mood and character. I am a little incoherent with awe.

Elsewhere at Necronomicon, a panel moderator suggested that Deep Ones were a bit overused in Mythosian fiction. I find this claim dubious, and at the same time have to admit that it sure is easier to find Deep Ones stories than tales of Yith or Mi-Go or K’n-yan or sorcerer worms or lizard ghosts or… Aside from Miskatonic University and the core deities, Innsmouth is the point on the Lovecraft Country map that draws us back, over and over, like a new-gilled woman seeking the sea. Maybe it’s because the story works so perfectly from both sides. Whether you’re terrified of discovering something inhuman in your ancestry or whether you yearn for it, “Shadow Over Innsmouth” will get under your skin. You might be invited (consensually or otherwise) to visit the Archives or Yuggoth, but Deep Ones are different. They’re part of you, whether you seek the connection or flee from it. And as Taaffe ably and subtly demonstrates, there’s horror to be found in both perspectives.

Lovecraft lived in the day of the one drop rule, and it echoes in Zadok Allen’s claim that “everything alive come aout o’ the water onct, an’ only needs a little change to go back agin.” One of the less acknowledged corrosions of white supremacy is that it puts those in power in a Lovecraftian universe: living on the thin skin of illusion that they matter, aware that the smallest violation might toss them down into the chaotic and horrifying depths below. In contrast to true cosmic horror, they make those depths themselves—but that truth wouldn’t have changed Lovecraft’s awareness of how swiftly and easily someone could lose their status as human. The same holds for many “taints,” from mental illness to the risk of poverty, equally capable of puncturing the fragile veneer of privileged reality.

The one drop rule is no longer on the books, but these fears haven’t vanished. You may have noticed.

Those of us who identify with Lovecraft’s monsters see a different horror. That’s probably why sympathetic Deep Ones—my own, Taaffe’s, McGuire’s—find it a little harder to go back to the water. In these versions it’s assimilation that terrifies, the loss of culture and tribal cohesion that follow on the heels of genocide. It’s the delicate negotiation of the mixed marriage, the question of whether your children will really be able to fit among your parents’ people. Taaffe perfectly embodies those challenges with a mixed Jewish/Dagonish marriage, where both sides must have shared those fears. I would happily read a whole other story, or novel, consisting solely of Anson’s parents discussing holiday customs.

No, not quite. The conversation I really want to read is the one about the sacrifices. On the hinges of the year, with the lottery of consenting family members—but always, somehow, even post-diaspora, they always have enough volunteers to anoint their newly aquatic with the blood of fishes and the blood of humanity. It adds a perfect edge to the story, and Anson’s family and culture are so fully drawn that I really want to know what his father thought about that aspect of his wife’s heritage. It’s not exactly the same thing as watching your spouse eat bacon on Saturday mornings, is it?

If I were Ron Penders, I would have sat shiva.

Anne’s Commentary

As mentioned in last week’s comments on NecronomiCon 2017, Ruthanna and I had the privilege of hearing Sonya Taaffe read from her work. She began with poems, then followed with a selection from “All Our Salt-Bottled Hearts,” which she said was her only truly Lovecraftian story. Talk about knocking the ball a couple miles out of the park in one time at bat and one swing!

Some “prose poetry” we can rightly describe as a shade of purple, from trembling pale violet to midnight aubergine. “Salt-Bottled Hearts,” on the other hand, has the vivid intensity of poetry, the striking use of image, without reading as overwrought or precious in the least. Here poetic sensibility serves a narrative well-suited to its strengths because well-suited to the protagonist’s habit of introspection, to the stream of memory and epiphany (or re-epiphany) which his encounter with a similarly thwarted “cousin” starts flowing. It’s the kind of story that deserves rereading, that merits pausing to leaf through its layers and allow its precise description to bloom into terrible beauty. Take, for example, this passage about cousin Isobel and her parents:

“Fabulous as a unicorn, twenty years old and already lashless and browless, the bones of her skull warping beneath her skin like the grinding drift of tectonic plates, her father’s blood nearly bursting her veins in its eagerness to reach the sea. Her mother had gone willingly to a bride-bed of rockweed and clamshells and borne her much-wanted sea-child in a haze of antipsychotics, already dissociating at the smells of salt and blood; her scars had nearly healed in nine months, but they shocked the obstetrician anyway.”

Whoa, that tectonically warping skull! That wedding couch of weed and shell! Those doc-shocking scars, presumably made both by shells and spousal claws! In a paragraph, Taaffe conjures by implication another whole tale of Deep One-human relations, the horror and the eroticism, the “haze of antipsychotics” suggestion of pre- and/or postnuptial madness, the lure of the sea for the inhabitants of both sides of the shoreline, for ocean-born blood that bursts veins to return, for a sea-child much-wanted by her landbound mother.

I could fill the rest of my allotted space with examples of the way Taaffe uses poetic technique to characterize Anson and heighten the poignancy of his situation—his genetic tragedy, so to speak. His genotype makes him one of the scattered children of Innsmouth, but “the fall of Mendel’s dice” has left his Deep genes unexpressed, his phenotype entirely human. He’s not as unfortunate as the partially-changed Gorgo. She dreams of an undersea life of immortal glory, the sea draws her with cruel intensity, only to reject her. Anson tells himself the smell of the sea is only “distance and salt” to him. But it’s also “wild as a gull’s cry on the wind.” Wind can also carry to him a “salt damp…like iridescence off a scale.” Names “rill” from his mother’s tongue “like a net of bubbles.” Gorgo’s laugh is “bitter as brine.” Tony’s voice runs on “like the tireless line of the sea,” dispelling Anson’s “choppy” dreams, waking him enough to notice a deep-sea bioluminescence in the clouds. Tony’s sigh, too, is like “a backwash of spindrift.” Frost on a window is like “a sea-spell over sand.” A man’s bracelet runs “against his dark skin like a meltwater of pearls.” Again, again, again, Anson perceives the world, makes his similes, in oceanic terms. Is he less painfully stranded than Gorgo after all? Gotta wonder.

“All Our Salt-Bottled Hearts” tackles an aspect of the Deep Ones infrequently addressed in, ahem, any depth, and that’s the biological and psychological details of the Change. Also the variable expression of Deep One exogenes in the human hybrid offspring, down the generations. The other story in which we’ve seen it profitably examined is Seanan McGuire’s “Down, Deep Down, Below the Waves.” In keeping with the tone of semi-muted tragedy in “Salt-Bottled Hearts,” Taaffe offers no options for stranded hybrids Anson and Gorgo. McGuire’s protagonist, on the other hand, will leave no potential Deep One behind, or even delayed, not if Science can offer an intervention! Which, in her capable hands, it apparently can.

Not that Taaffe’s story, darkly gorgeous as it is, needs any alteration. Still, just for fun, let’s suppose that McGuire’s Violet Carver should run out onto the Gloucester beach with a parmesan-loaded pizza in hand. Well, Anson and Gorgo must be pretty hungry after all that wandering in the cold salt-spray. A few slices of Violet’s pie would probably go down sweet, maybe with a side of Mama Carver’s chowder, and then?

Could be Y’ha-nthlei, here we come!

Next week, Gemma Files takes on the legacy of Marceline Bedard in “Hairwork.”

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots (available July 2018). Her neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Dreamwidth, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.