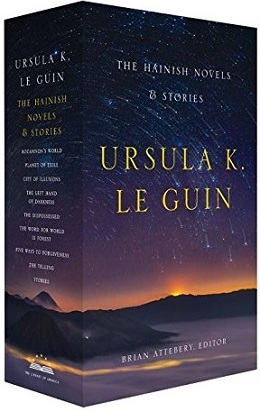

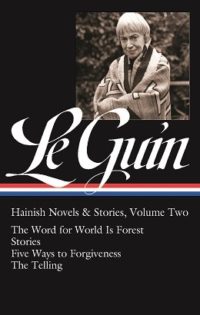

A year after their release of Ursula K. Le Guin’s complete Orsinia works, the Library of America has released a stunning two-volume set collecting the author’s most famous sci-fi works. The Hainish novels and stories do not unravel like a traditional series—the author even chafes at their common designation as a “cycle”—but they are, at least, connected by a shared universe, pieces and fragments of a shared history, and an ethos of exploration and compassion that is arguably the touchstone of Le Guin’s entire oeuvre. The Hainish worlds (including our own Earth, or Terra) were propagated millennia ago by the people of the planet Hain, and are now gradually reuniting under the interplanetary alliance of the Ekumen. From anarchist revolution to myth-inspired hero tales, the stories of the Hainish planets are as wide and variable as their inhabitants. And yet it was only a matter of time that they be collected in one place.

The Left Hand of Darkness and The Dispossessed, both included in Volume I of the collection, are two of Le Guin’s most widely read, studied, and praised works of fiction. Placed alongside some of her earliest novels and lesser-known stories, the novels are cast in new and stunning light. They become pieces of a story bigger than themselves. Doubt is thrown on their truths and authoritative readings. Where other compendiums and collections might serve to build a more solid and definitive world-building project, Le Guin’s stories become weirder and more complex when placed side-by-side. This strangeness—in a collection whose theme is often uniting under strangeness—is as fitting and thrilling as it is messy.

[More thoughts on authority, plus the Table of Contents]

I wrote in my review of the LoA Orsinia collection that the new edition lent Le Guin’s fictional European country a certain authority or reality. It has been noted time and time again that Le Guin’s works are anthropology-inspired; but maps, timelines, linguistic notes, and shared cultural touchstones make the collection feel even more like an anthropological study than it would on its own. It should also go without saying that a large, well-regarded publisher like LoA all but inducts its selections into an American literary canon (however problematic the concept of a canon might be). The Orsinia collection thus becomes an authority text not just because of its realistic claims to a fictional history and culture, but because it is definitive and well-regarded by a literary elite. This all holds true for the Hainish collection as well. No matter that planets like Werel and Yeowe are more obviously unreal than the nation of Orsinia—they are presented in a minimalist designed hardback edition with appended notes on their language and natural history, and are as real as any fictional pair of planets could hope to be.

And yet Le Guin cheerfully troubles her own waters. She freely admits in the collection’s introduction and appendices that she never intended the stories to form a canon, and that she changed her mind multiple times in the thirty plus years of their writing. Universe-changing concepts like mindspeech appear and disappear, depending on the story. Timelines are muddled. Gender roles and social commentaries shift and flow. If you read the Hainish novels and stories over the course of thirty years, or even over the course of one, it might not be as noticeable. But reading them as a collection is its own unique experience. For one thing, readers will see the tides of change in our own twentieth century history reflected in Le Guin’s changing ideas (her 1987 redux of the 1976 essay “Is Gender Necessary?” is an amazing example of this). They’ll find a naturally talented author sharpening her skill over time, honing her voice into something unique and vital. They’ll also hopefully discover something that the Hainish stories were saying all along: that there are no authoritative texts, and that we create meaning piece-by-piece, story-by-story, even when those stories are contradictory.

Maybe the best example of this is the last story in the collection, Le Guin’s 2000 novel The Telling. The somewhat graceless and rushed novel seemed to me at first to be a bad note to end on. It hurries along plot points in favor of heavy-handed social commentary, and its ending leaves a lot to be desired. But, thematically-speaking, the novel also perfectly wraps up the rest of the Hainish stories. In it, the protagonist Sutty struggles to complete her work as a historian of the Ekumen while on the planet of Aka. She has arrived on the planet after a cultural revolution wiped out much of their peoples’ written history and literature; a new language has replaced the old, and a ceaseless push towards scientific progress has eradicated philosophy and religion. Authority, on the new Aka, is delivered from the top-down. Gradually, Sutty uncovers the Aka that has gone into hiding, a religion most accurately called the Telling. In the Telling, people share stories with one another—sometimes contradictory, sometimes short and sometimes epic. The morals of these stories are not always clear, but their meaning is this: to listen, to share, and to collect.

The LoA Hainish collection, like the history of Aka, lacks a central or hierarchical authority. The meanings it presents are many and various, and open for interpretation. The fact that the stories sometimes contradict one another or change throughout their tellings, is not a flaw, but instead their central strength. Even without the beautiful meanings that it unfolds, the LoA Haicollection would be worth seeking out for purely aesthetic and practical reasons. But rest assured, too, that you’ve never read Le Guin’s Hainish tales quite like this.

The full table of contents, along with the dates of publication and featured Hainish planets are listed below.

Ursula K. Le Guin: The Hainish Novels & Stories is available from Library of America.

Read Le Guin’s new introductions to both Volume One and Volume Two of the collection here on Tor.com

Table of Contents

Vol. I

Vol. I

- Introduction

- Rocannon’s World (1966, Fomalhaut II)

- Planet Of Exile (1966, Werel)

- City Of Illusions (1967, Terra)

- The Left Hand Of Darkness (1969, Gethen)

- The Dispossessed (1974, Anarres | Urras)

- Stories

- “Winter’s King” (1975, Gethen)

- “Vaster Than Empires and More Slow” (1971, World 4470)

- “The Day Before the Revolution” (1974, Urras)

- “Coming of Age in Karhide” (1995, Gethen)

- Appendix

- Introduction to Rocannon’s World (1977)

- Introduction to Planet of Exile (1978)

- Introduction to City of Illusions (1978)

- Introduction to The Left Hand of Darkness (1976)

- “A Response, by Ansible, from Tau Ceti” (2005)

- “Is Gender Necessary?” Redux (1987)

- “Winter’s King” (1969 version)

Vol. II

Vol. II

- Introduction

- The Word For World Is Forest (1972, Athshe)

- Stories

- “The Shobies’ Story” (1990, M-60-340-nolo)

- “Dancing To Ganam” (1993, Ganam)

- “Another Story Or A Fisherman Of The Inland Sea” (1994, O)

- “Unchosen Love” (1994, O)

- “Mountain Ways” (1996, O)

- “The Matter Of Seggri” (1994, Seggri)

- “Solitude” (1994, Eleven-Soro)

- Story Suite: Five Ways To Forgiveness

- “Betrayals” (1994, Yeowe)

- “Forgiveness Day” (1994, Werel)

- “A Man Of The People” (1995, Yeowe)

- “A Woman’s Liberation” (1995, Werel)

- “Old Music And The Slave Women” (1999, Werel)

- Notes on Werel and Yeowe

- The Telling (2000, Aka)

- Appendix

- Introduction to The Word for World Is Forest (1977)

- “On Not Reading Science Fiction” (1994)

Emily Nordling is a library assistant and perpetual student in Chicago, IL.