A group of friends, a pair of lovers, and the tussle between love, addiction, and what comes next. Otto, a former addict, grateful and indebted to his lover Trevor, is faced with temptation and the threat of disaster, but he’s fighting it. Fighting it in a future where matter can be reprogrammed and anything could happen, good or bad.

Vashti’s polymer was purple-flecked, fist-sized at normal density, and we all watched dutifully while she tapped at her phone and cycled through the rather stale parlor tricks of turning the lump of soft pseudo-styrene into a tiny dinosaur, a sword, a little stripper who shrank to the size of a quarter and then ballooned to Labrador-Retriever proportions. The roast was taking too long and Trevor was in the living room being charming instead of mixing up the salad dressing—and why did I have to have such a charming boyfriend?— and the doorbell was ringing and no one was answering it and I huffed my way to the door and forced a smile onto my face as I wrenched it open.

As soon as I saw him, I knew I was doomed.

“Hi,” he said, “I’m Aarav.”

“Vashti’s brother,” I said, seeing his bear-beard and wolf-smile and feeling my stomach plummet, “of course.”

His hand was hot in mine.

I’d been doing so well. I’d fought temptation at every turn. I’d never cheated on Trevor, not once, never mind how every stroll down a Chelsea block flashed a couple dozen lean-and-hungry golden-boy-or-silver-fox grins at me, and surely just once wouldn’t hurt—except that I knew, from the still-raw psychic wounds of my momentarily-vanquished crystal meth addiction, that once was all it took to bring your life crashing down into the gutter. Not because one snort would wake you up covered in blood at Central Booking or Lincoln Hospital, but precisely because it would not, because you’d get away with it, and remember how magnificent it was, and forget every awful consequence, and keep doing it, until you’d lost everything.

And now Once had walked into my living room, his ass perfect and his eyes alive with the knowledge of what a weak creature I was. And I was doomed.

I led him into the living room.

“Your polymer is impressive,” Fennis was saying to Vashti in a superlatively unimpressed voice—but then again he’d never liked her, and why had we invited him again? —and produced his own polymer, a jagged solid jelly in a glass jar, marbled and muddied with a mix of clear first-generation inert polymer and the darker second-gen stuff that could change color, cast light, play videos, and he opened the app on his phone and we watched it come to life, writhing and thrashing and then elongating, sharpening, shattering the glass with a single explosive motion. It penetrated Vashti’s polymer, which denatured and was assimilated into Fennis’s. Before her cry of protest was completed his polymer spat hers back out and both stood there as though the whole thing had never happened. His finger swirled on his phone screen and the thing took a wobbly bow. Everyone applauded.

“Field control assertion like that must have cost you a pretty penny,” she said sourly.

“Not really. Some boys on my block are battlers, they love sharing their new tricks.”

“Otto is working on a story about polymers,” said Trevor, patting my thigh proudly when I came to hover over him and silently command him to return to the kitchen. He was using That Tone, the one that said Be chatty, be witty, be handsome, perform. “About the dangers. Aren’t you, honey?”

“I am,” I said, doing my best to simultaneously smile at our guests and glare at him.

“Vastly exaggerated, those dangers,” said Aarav, who I’d been doing a damn good job of not looking at since he walked in the door, except now he was talking so I had to look, and, yes, damn, there it was, those broad chunky shoulders, that ample bottom he was surely standing in three-quarters profile precisely to best display, and I hated Vashti so much in that moment, for calling that morning to plead with us to make space for him at our annual vernal equinox supper—“He just moved to New York, he hardly knows any other gay guys, I feel so bad for him.” I gave him the most withering smile I could find. He continued, “No more dangerous than cell phones or networked microwaves, and no one’s writing articles about that.” His face was warm, almost sad, and the multiplex of my mind stuttered to life with a dozen different pornographic scenes starring only us.

“You should interview Aarav for your story,” Vashti said. “He works on polymers!”

“Not exactly,” he said. “I do communications for Verizon. My unit does focus a lot on polymer-related promotions. The kaiju battle community is a very important demographic.”

“You two talk,” Trevor said. “I’ll go make the dressing.”

And what could I do, but be seated, beside Aarav, and curse the smallness of our couch, because I could feel the heat of his leg where it pressed against mine, and surely everyone in the room would know, at once, how badly I wanted him, what a disgusting pervert I was? And, of course, matters were made immeasurably worse by his wisdom and sense of humour—he had everyone giggling, which meant I had to giggle too, lest someone wonder why I wasn’t.

“I heard that hammer sales are plummeting,” someone said.

“Screwdrivers too,” said someone else.

Ten people at our party, and suddenly everyone had something to say about nanopolymers. I didn’t care one way or another about the damn things. They assigned me the story because I’d cultivated relevant contacts on previous articles. I drank my gin and tonic in one long gulp and switched to wine.

Aarav would not let me stay silent. When I failed to weigh in on whatever theory or fact or opinion was passing around the room, he touched my arm and said, “What do you think, Otto?” Was that because he was a kind and generous person? Or did he know the game I was playing—the game of hunger, of lust, of trying to be good—and could play it just as well as me? The problem with returning to the smiling happy world of dinner parties and office jobs and responsible adults after a long addiction is that you’ve seen people at their worst, especially yourself, and it’s hard to assume the best about anyone.

“When my old broom wore out, I didn’t buy a new one,” someone said. “So much easier to just download broom instructions and beam them into your polymer.”

“Dinner!” Trevor called, and I sprang from the couch. He frowned at the glass in my hand, made stern eye contact.

“We never buy new toys for Tripp anymore,” said Fennis, leading the troupe into the dining room. The oven had heated the whole place up so high that we’d had to open a window, and an undercurrent of cold city winter wind tugged at our sleeves. “Whatever he wants, we can just make it on the spot. Now the problem is, he keeps on begging us for more and more putty! Quite the status marker at school, how big your total polymerload is.”

“Kids are so insufferable with it,” someone else said. “I made the mistake of calling it ‘magic clay’ the other day and my seven-year-old said ‘It’s not clay, it’s a plastic-based gel. And it’s not magic, it’s got millions of tiny machines inside of it that respond to commands from wireless devices.’ Can you imagine?”

We could all imagine.

“So is your article about the death of the manufacturing sector?” Aarav asked, sitting down beside me, and his eyes were immense, so light they looked like gold. “They say we’re less than five years from polymer automobiles. Imagine being able to upgrade to the latest car model with just a software update!”

“That’s ridiculous,” someone said. “Toys and simple tools are one thing, but shape-memory polymers are a long way from being able to emulate complex machinery. Nanite stereolithography doesn’t even do batteries very well—the storage capacity is shit, they overheat…”

“I don’t know,” someone else said. “I spun mine into a laptop, on a business trip last month. Wasn’t winning any beauty contests—battery was like a weird bloated tumor on the back, and it kept, I don’t know, writhing—but it got the job done.”

“They let you take programmable matter on a plane?”

“No, of course not,” she said. “But Virgin is doing this thing now where you can give them your polymer at the gate and get a bar code voucher, and then when you get off at your destination they give you the exact same amount back. They even get the blend of first-gen and second-gen stuff precisely right.”

“Delta, too,” someone said.

I prayed for them to stop. I drank a third cup of wine praying it, practically chanting it out loud. I wanted them to be quiet and I wanted them all to get the fuck out. Especially Aarav.

Of course it was silly. No one could see the filthy thoughts I was thinking, how precarious this lavish scene of domestic virtuosity truly was. No one suspected how unhappy I was, how hungry. No one but Trevor, who put his hand out to stop me when I picked up the bottle of wine.

Trevor was older, wiser. He’d picked me up out of the gutter—or, more accurately, picked me up off the floor of a dark room at a particularly nasty sex party. It was his apartment we were in; his job that bought the roast and the good wine and the cheeses on the platter. And I loved him. I truly did. But he was good and I was bad and his smile said he knew I was a fraud, and loved me anyway.

“So?” Aarav asked. “Your article. You haven’t said what dangers you’re covering.”

“Hacking,” I said, passing the rolls, pleased with how perfect they’d come out, how brown. The roast, on the other hand, lying in a dish of its own blood, was a different story. Our oven heated unevenly. One corner was blackened and burnt. Absolutely everything in the world was wrong.

“What, like that whole thing about how terrorists might make your polymer bracelet turn into a razor blade and slit your wrist open? I thought people gave up on that kind of hysterical scare-mongering two years ag—”

“Not that, so much,” I said. “There’s this whole new wave of what they’re calling aggregative malware, which could in theory cause polymers to compulsively link up. Predictives anticipate some pretty destructive scenarios as a result. Especially once the third-gen stuff comes out…”

“Interesting,” he said, his sturdy forearm innocuous on the table beside mine. Against mine.

“Not sure I buy it, myself,” I said. “Though lots of smart people do.”

“Thinkpieces will be the death of us all,” Fennis said. “Every other day people are trying to tell you we’re sowing the seeds of our own destruction with some stupid thing. No offense, Otto.”

“None taken. Anyway, I’m with you. Even if it’s true, what are we supposed to do about it?”

Everyone agreed that we were helpless, guiltless.

Trevor turned his head in a slow circle, his smile immense, proud, blissful at what we’d built, what a life we had, what wonderful friends, what a stable glorious home he’d made for me. For us. I tried my best to smile back.

I loved him. So, what was I hungry for? What did I still want, why couldn’t I keep from imagining ravaging Aarav in the wreckage of our living room?

“It is inherently less secure,” someone said. “You can’t encrypt them in the same way. Your shaping app can lock the nanites, but only until something with a stronger field comes along. It’s fundamental to how the distributed CPU functions.”

“I went to a kaiju battle last week,” Vashti said. “That’s the whole point of them, that struggle for control. Some pretty big mother fuckers.”

“I’ve only ever seen the web videos. And that awful reality competition show.”

“It’s so much fun,” she said. “Grimy, and a little bit scary. Some of these creatures look like something from a nightmare. Most fights, there’s this part at the end, what they call the death roll, where it’s essentially one big Silly Putty blob wrestling with itself to see which one has the stronger field control. People sitting in the front rows say they can feel their polymers moving in their pockets.”

“Did you read that article, The Future of Hunger in the Age of…”

Everyone had read that article.

“Good lord,” Trevor said, finally. “This is worse than lunch with the straight guys from work, hearing them talk about football!”

“Have you guys seen I Can See Right Through You yet?” I asked, because Trevor had me well-trained, and nothing derailed a boring conversation better than a controversial art/horror film. “That guy they got to play the demon lover was hot.”

The night went on like that. Everyone happy but me—or everyone doing just as good a job as me of faking it. Snow and wind hammering at our windows. People peeling off, departing with regrets as the night got longer and the storm got worse. Me doing my damnedest not to make eye contact with Aarav, not to notice how smart he was, how once he’d voiced an opinion on something it just felt right, like my own, like it had always been my own. I tried, too, not to notice how nice it was to hang out with another gay guy who wasn’t Trevor, Trevor whose prim paranoia about my inherent weakness kept us from all but the most unfuckable friends.

“Shit,” Aarav said, past two, the last guest, long after his sister had left, seeing the snow of an early-spring surprise storm stacked against our glass. “It’s piled up so much!”

“Subways run all night,” I said, cheering inside as I went to get his coat. “Best part of New York City life, newbie.”

“I have my car,” he said. “I know it’s not practical for the city, but I just can’t bring myself to get rid of it.”

“That sucks,” Trevor said. “It isn’t safe to drive in this. Should be all plowed and cleaned-up by morning.” His eyes flitted to mine, made the smallest frown, a fraction of a second, long enough for me to read whole oral epics into it—he could see my weakness, knew what I ached to do to Aarav, saw how unwise it would be to have him in our house for a single unnecessary extra second. But he could see, too, with his exquisite WASP etiquette, that there was no other option than to say to him: “You can crash here for the night, if you want.”

“You sure?” Aarav asked, looking to me, and I was conveniently taking a long sip of wine at that point, screaming inside, No don’t do this, but eventually the sip had to end, and I nodded as enthusiastically as I could.

He did the dishes. We made up the guest bedroom. We all watched polymer videos online, saw the terrifying monsters and fancy clothes and seawalls and emergency shelters that people had built from nanopolymer, watched trailers for three or four new polymer-based reality competition shows. We placed our polymers and our phones in a heap by the charging hub. I was furious with Trevor for extending the invitation, with myself for getting so drunk, for enjoying the husky sound of Aarav’s laughter so much.

“You shouldn’t drink so much,” Trevor said, once the bedroom door was shut behind us.

“What?” I stammered, all false innocence, because, of course I shouldn’t. “Why?”

“You embarrassed yourself. Practically drooling over Aarav.”

“I was not!” I said, reddening, from alcohol and guilt, shame and defensive anger.

Trevor shrugged and undressed, like it was all too obvious and inconsequential to argue over. I’d been surprised, when we first started dating, when we had The Talk about our sexual parameters, that he insisted on monogamy. “Addicts never stop with just a little,” he’d said, and what could I say to that? What could I say whenever he brought that up, which was often—whenever he wanted to end an argument? And what could I say now? Because any argument I offered would be a lie. He was right and I was wrong, he was perfect and I was wretched. I slid into bed beside him, felt the whisper of the wind from where we’d left the window open, heard the clanking of our radiators trying too hard. I touched his hip with one hand, which he seized, and held.

He had been right, too, about my having had too much to drink. I slept poorly, in and out of hungry dreams—burnt meat and hairy barrel chests—too dizzy to lay still, until I sat up with my head spinning and my stomach doing its best to expel the charred corner of the roast that I’d taken for myself so none of our guests would eat it and think less of us.

Dawn, almost. The sky just starting to brighten past the normal city luster of snowy winter nights. Everything else a blur. Was I home? Was I back in the hallway of that filthy apartment building where a john had kicked me out and I’d fallen asleep outside his door? I staggered towards the bathroom, imagining myself projectile vomiting absolutely everything absolutely everywhere.

I had to puke. This much was true. But was that why I was out of bed? I walked slowly, silently, suspecting in my groggy fuddled state that this was all an elaborate ruse to watch Aarav sleep, taunt myself with his tantalizing profile and hope for a glimpse of a furry bare arm or the sheet-hidden outline of an erection. But would I be able to stop myself there, in the doorway, watching?

Is this me? I wondered, peering into the dark. Am I capable of this?

What I saw was so much better than mere sleeping nudity. And so much worse.

His ass. Bare, damp with sweat in the overheated apartment, moving, a dire implacable rhythm. The chubby, perfect, naked bulk of him. My boyfriend beneath him. Trevor’s groans of pleasure. Aarav’s hand, clamping over Trevor’s mouth to quiet him.

They didn’t hear me. I’d never seen Trevor eyes look like that. I didn’t move. I watched helplessly, wanting to, not wanting to want to. Memorizing what I saw, for the long lonely nights to come. Bracing myself for the apocalypse that was on its way, almost here, that would arrive the moment I opened my mouth to shout hate and rage at them. Wondering why I couldn’t open my mouth.

#

Coffee in the camps was always a crap shoot, most mornings merely warm brown water the color of iced tea when half the ice has melted, but once in a while they’d get a donation of decent stuff, several bins of Folgers sent by fundie jocks or soccer moms in some idyllic safe small town who did a Kickstarter or bake sale to send toiletries or pleasantries to the poor benighted New York refugees, and that’s what kept us coming back, every morning, the hope that we’d get something other than shit—Upper West Side dowagers and Brooklyn graffiti virtuosi waited in line together, sweaters held tight against the wind, and then we drank the coffee we were given, and shivered together in the long windy tents, beside the stripped-bare orchard, and tried not to think about what lay behind us, or what lay ahead . . . and it was there, in the Canajoharie resettlement area, in a forest two hundred miles north of the crater where my city used to be, cradling a cup of so-called coffee, that I saw Aarav for the second time.

As soon as I saw him, I knew he was doomed.

Six months had passed, since the last time I saw him—the night he spent in at our apartment. Six months, since polymer kaiju stomped New York City into rubble. He’d lost weight, wore dark sunglasses now. The rest of him was unmistakable.

I won’t lie: my first emotion was happiness. To see someone I knew, a memory of my vanished world. My mouth opened, eager to call out his name. But happiness faded fast, replaced by lust, which triggered rage.

“And to think,” someone was saying, “we used to think it’d be rising ocean levels that would wipe us out!”

“Stop being melodramatic,” said someone else, because everyone was an expert when it came to the polymer kaiju uprising, and these breakfast-table conversations were interminable, “We’re not wiped out. All those attacks barely made a dent in the total human population of the planet. Rising ocean levels still have plenty of time to destroy us.”

“All our fault, either way.”

“Is it?”

“You don’t think so?”

“What else could we have done?”

“That’s exactly the problem. Keep telling yourself you’re helpless, pretty soon you’ll start to act like it.”

“They’re still out there,” Aarav said, and his voice was just as wise, just as insightful—except now I could hear his wisdom for what it was, what all of us were doing when we tried to sound like we understood what was going on around us. Cave men at the campfire trying to feel less afraid. “Just because we can’t see them, doesn’t mean they’re not coming.”

Rage lit me up inside. Revenge plots percolated. Bloody murder tingled in my fingertips, aching to be let out.

And it felt…familiar. Murder wasn’t meth, not exactly, but it brought back the old buried joy, the bliss when I’d scored enough to last me through the whole weekend, the ecstasy before the first hit, when my head was still full of perfect scenarios, the thousands of sexual partners and the endless dance floor hours and the loud howling down late-night residential streets. I looked at Aarav and I felt alive in a way I’d spent years trying not to feel. Except that now there was no reason not to. No Trevor telling me to stop. No police waiting to arrest me for possession or prostitution.

Because what else did I have? After all I’d lost, here, at last, was something I could do. Something I could control.

What are the odds, I thought, but I knew the odds, could do them in my head, math had always been my strong suit, back when math mattered—two thirds of the city’s population made it out alive, half of them ended up in a camp, and there were four possible camps. So, approximately an 8.33% chance that we’d both survive, both have nowhere else to go because our nearest relatives lived too far away for the perilous land trek, and he would end up in the same camp as me.

Shouts, from a corner of the tent. Kids fighting over the radio. Music came and went, replaced by a tired-sounding woman reading bad news. Beside me, a bandaged man read a newspaper whose front page sported a particularly gnarly spider woman kaiju.

I thought of hiding from Aarav. Keep my distance, bide my time while I concocted some spectacular revenge.

But why should I hide? He didn’t know that I knew. That I’d seen. The next morning, over coffee and complaints of hangovers, he and Trevor certainly hadn’t said anything about it.

And neither had I. Not that day, and not the next. I waited. Heart and mind breaking from the stress of wondering when it would happen, when Trevor would tell me it was over, he’d found someone new, he was tired of my weakness and my damage.

Five days later, when it was clear that he wouldn’t be bringing it up, I resolved to bring it up myself. My nerve failed at dinner, that night, but the next day, surely—

The next day Trevor died in the ring of radioactive fire that took out a third of us.

So: I would not hide. I moved closer. Aarav’s arms, like mine, were taut and muscular from running the hand-cranked generators that powered the radio, the medical equipment, batteries for approved non-networkable electronic devices.

Somebody ate the bacon off his plate, and I saw that Aarav was blind.

The first kaiju assault was an accident. A faulty German software update rolled out in select markets; conflicting code in a bloated proprietary phone manufacturer operating system; aggregative commands accidentally exploiting field-control backdoors to cause polymer to seek out polymer. No shape, no animating intelligence, just an ever-increasing plasticine blob of horror that bored through walls, crushed buildings, leveled streets until it had assimilated every shred of shape-memory polymer animated by the same operating system and come to a sated stop. At which point forty German cities were mostly gone.

After that, everything happened so fast. Four hundred million tons of styrene polymers in active use worldwide. The software update in question was easy to copy, change, twist.

“Aarav!” I said, standing over him, enjoying several milliseconds of him smiling and looking confused and ashamed.

“I’m so sorry,” he said, gesturing to his sunglasses. “I’m—”

“Otto!” I said, and took his hand. “Otto Trask? You stayed—”

“Otto!” He cried, his mouth a trembling crooked rhombus of happiness, his face darkening like he was about to cry. No flicker of shame, no hint of guilt. He stood and hugged me, hard. “Is Trevor…”

“No,” I said. “Probably the same blast that took your eyesight.”

Aarav hugged me harder. He smelled good. I hated him worse for it.

“And Vashti?”

It took him so long to answer me. “Gone too. Where were you, when it happened?”

“Home. Writing.” In the room where you fucked my boyfriend.

Leaves had piled up at our feet. The forest smelled sharp and smoky. I smiled for what felt like the first time. When Trevor died, all my anger at him turned on myself. I’d been such a bad boyfriend. I’d been so hungry. He’d been smart enough to see it. My fault, that he’d fucked Aarav. My hunger.

One week after Germany, Ukrainian resistance fighters gave six hundred thousand dollars to the nineteen-year-old kid who came in third on the second season of Polymer Kaiju Prime, a crowd favorite with a twelve-foot-tall version of a certain famous Japanese movie monster. He gave them a flash drive with his monster’s schematics on it. Then they pegged it to a more aggressive form of the aggregative software and added in a remote control. The next day the residents of Russia’s two largest cities found that something was compelling their polymers to move on their own, heading straight for the nearest storm drain or toilet. Breaking through whatever they used to try to contain them. That evening, two four-hundred-foot-tall clear Godzillas rose out of the Moskva and Neva Rivers. They couldn’t breathe fire, back then, but they didn’t really need to. Helicopters dropped bombs on one of them, and they did almost as much damage as the monster did. The monster’s polymer fragments re-assembled and she continued on her merry way.

“What’s your plan?” Aarav asked, his hand holding mine, with no lust or lewdness this time, just fear and hunger and loneliness and need, and I smiled, at it, at his weakness, at the knowledge of how I could use it to destroy him.

“Watch my money dwindle. Pick up odd jobs where I can.”

“Yeah,” he said. “Me, too.”

Dogs barked. So many people in the camp had dogs. A gunshot in the distance: upstate boys hunting deer, like this was any other autumn, which for them it pretty much was. Girls in leather and camouflage swapped packages. Black marketeers, officially tolerated because they filled in the gaps that the under-resourced camp administration couldn’t.

Corporations, governments, out-of-power political parties, local militias—everybody started building their own monsters. People stockpiled polymer. Nations took steps to ban or destroy it. When the mayor of Quezon City ordered wholesale surrender from his own citizens, the subsequent stockpile was stolen by—or possibly sold to—a street gang, who made a handful of mid-sized monsters and used them to break their members out of several prisons.

Old hierarchies of power were inverted. Mighty nations were powerless to stop the rogue kaiju of terror cells and coder collectives. But we were being melodramatic, when we called it an apocalypse. Only a few big cities had been hit. Most kaiju dust-ups took place in geopolitical hot spots, contested spaces where conventional violence had been powerless to rupture the status quo: Kashmir, Tibet, Chiapas, the Northwest Passage, the Diaoyu Islands, Jerusalem. The North Cali/South Cali border. Easy to see them as monsters, to look in their eyes and see a malevolent intelligence, but they were still just machines, masterpieces of programming, doing what humans had programmed them to do.

“You have people who know you’re here?”

He shrugged. “Supposedly they keep people informed. But most of my people are in big cities, and who the fuck knows what’s really going on there?”

Every day now was chillier than the one before. New York fell in late March, and we’d been blessed with warm weather ever since. Almost October, now, and I felt it in my tightening testicles: the fear of winter, the stripped-down human animal whimpering in the wind.

I shut my eyes and I could see it, as it had been in the thousands of photos that people had taken and shared in the instants before they died. A three-headed white wolf, forty stories tall. Flames spiraling in the ruins at its feet. Stomach aglow in the dusk, burning brighter as its auto-generated nuclear reactor went critical.

“You know what I miss most?” he said. “About New York?”

“Getting stuck behind slow people on the subway escalator?”

He chuckled. “No. Worse.”

“The thoroughly-reasonable rents?”

“Shake Shack.”

“Fucking tourist.”

“I know!” he said, and laughed. “I’m sorry, I love a milkshake. It was my guilty pleasure. I’d only go late at night, when I was by myself, so no one would know.”

“It’s a damn shame,” I said. “You became a New Yorker just in time to lose the city forever.”

His laughing lowered, and wobbled, and somewhere along the way it became crying.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “I’ve just been so lonely. You can’t imagine.”

“I think I can,” I said.

“It’s so good to find you again.”

“Likewise,” I said, and meant it, my smile sincere, because here, finally, was something I could do, even if that something was murder.

I hugged him. He hugged me back, hard, grateful; blind, as Trevor had never been, to the wickedness inside my head.

I took in the scene around us, assessing my options. Looking for ways to make it look like an accident. Forest brightening with fall. The high cliffs above the Mohawk River.

Those. Those would do.

“Now you wouldn’t happen to have a stash of real coffee squirrelled away somewhere, would you?”

I laughed. “I wish.”

I didn’t do it just then. I could have. If I asked him, “Wanna go for a stroll,” promised him a blowjob or a cask of Amontillado, he’d have taken my hand and followed me anywhere. But I wasn’t ready. Had to plan. Write my lines. Rehearse.

And besides. We were in the crowded dining tent. People had seen us. Security in the camps was minimal, practically non-existent, but in the remote chance that his water-logged body turned up not far from here, was traced back to the camp, and someone came looking, I didn’t want to be the last person seen with him.

That’s what I told myself, anyway. That I was being smart. Not weak. Not hesitant. Not waiting for a way to talk myself out of it.

Not wrestling with myself over how badly I still wanted him.

“I gotta go,” I said. “It’s my shift at the hand-cranks.”

“Okay,” he said, looking crestfallen.

“Shift ends when the sun sets,” I said, squeezing his shoulder.

“I’m in Tent 57!” he called, and I heard him, and I did not respond.

I didn’t have a hand-crank shift. I scouted the location, the bluff where I’d bring him. I practiced what I would say.

I didn’t think about Trevor.

Every day, I thought about Trevor. Too-good-for-me Trevor. Comforting myself with the knowledge that I never did a single one of the awful things he’d always been expecting me to do.

I found the spot. I mapped out our steps. I waited until everyone had gone to dinner, and Aarav remained, alone in Tent 57, waiting for my return, like I knew he’d be.

“Wanna go for a stroll?” I asked, and watched him brighten.

Is this me? I wondered, while we strolled. Am I capable of this?

We walked between the trees. Leaves fell all around. None struck us. He was not as sexy as he’d been that night. He’d lost heft, and confidence. But I could feel his heat when we walked together. Smell his body. Feel myself stiffen.

And why shouldn’t I have him? Before I murdered him? I had denied myself this pleasure, before, for love, for stability, for the sake of my happy home, and look where that had gotten me. I had been so good.

When we got to the cliff, when we stood at its edge and only I could see how close he was to doom, I grabbed him by the shoulders and pulled him into a kiss.

It lasted a long time. But it didn’t last long enough. Because when it was over he said, “Why didn’t you say anything?”—and I knew, from the tremble in his voice, exactly what he was talking about, but of course I had to say:

“Say anything about what?”

“About what you saw. That night. Me and Trevor.”

“You knew?” I said, and the rage was back, grown to kaiju proportions, and my grip tightened on his shoulders, slid down to take hold of his biceps and squeezed to stop my arms from shaking. River wind roared up hungrily from far below.

“Trevor heard you. Behind us. He told me later.”

“Trevor? He…?”

“He knew. Of course he knew.”

He knew. Of course he knew.

“I’m sorry,” Aarav said. “I can’t believe I did that. There’s no excuse. I’d had a lot to drink that night, and I woke up to him kissing me, and—”

“Don’t,” I whispered. The wind stood still. The river went silent.

“Shit,” he said. “Sorry. I’m sorry.”

We were so close to the edge. The most effortless pivot of my hips was all it would take. So why couldn’t I move?

“I called you,” he said. “The next day.”

I said “Liar,” but wasn’t sure if any sound came out at all.

“I did. On your cell. Trevor answered. That’s how I know he knew you knew.”

It wouldn’t have been the first time Trevor had taken a call meant for me and told them to go to hell, and purged the call from my cell phone log. Dealers, usually, but sometimes exes who he feared would pull me back into the life. And sometimes friends. “Aren’t you the chivalrous adulterer, making the gallant gesture of rubbing my nose in how you’d fucked—”

“Otto, no,” he said, and there was a realness in his voice, a gravity, and I knew that he was going to tell me the truth, a truth I didn’t want to hear but could not escape. “I called to tell you that you deserved better. Better than Trevor.”

“Stop,” I said, again. The wind was back, strong, screaming. My grip relaxed. Tears gathered.

“What you two had, that wasn’t healthy. He was awf—”

I dropped to my knees because it was the only thing I could think of. To stop him talking, to silence the wailing inside my head. I expertly unbuckled his belt. Because he was right, about Trevor, and I’d always known it, and I’d told myself I was wrong, that it was my weakness talking, my wickedness.

“Up,” Aarav said, gruff and tender, pulling me off my knees. “Stand up.”

Moments later I was up against a tree, arms embracing it, the bark rough and good against my face, his hips grinding against my backside. I felt him fatten, expand, and I had a ridiculous and irrational flashback: Vashti’s purple-flecked polymer. The little dance it did. How harmless it seemed. How small. How secure we all felt, in that too-warm living room.

They add up, the tiny harmless things we harbor, the little guilts and baby sins, the crimes we think we only commit against ourselves. The indignities we suffer. The stories we tell ourselves about how wicked we are. Or how helpless. They can crush cities, raise seas.

“You want it?” he asked, poised to enter.

“I want it,” I said, because I did, I wanted, because all I was was wanting, was hunger. But hunger is no crime. And I was no monster.

A low rumble shook the air. I turned my head, looked up. The moon was full, illuminating the winter cloud cover. But something was up there: silent, immense, jet black, like a wound in the bright sky. Something flew. High; so high. Far to the west of us. A manta ray kaiju; a flying polymer as big as the George Washington Bridge. Massive fin-wings propelled it through the sky with slow majestic strokes.

“What is it?” Aarav asked, his breath hot in my ear.

“Nothing,” I said, staring into the sky. The monster flew, free as any animal could ever be, and my heart soared with it. What was it doing? Where was it going? I watched it diminish into the distance, moving leisurely for all its speed, like a lifted burden leaving me behind.

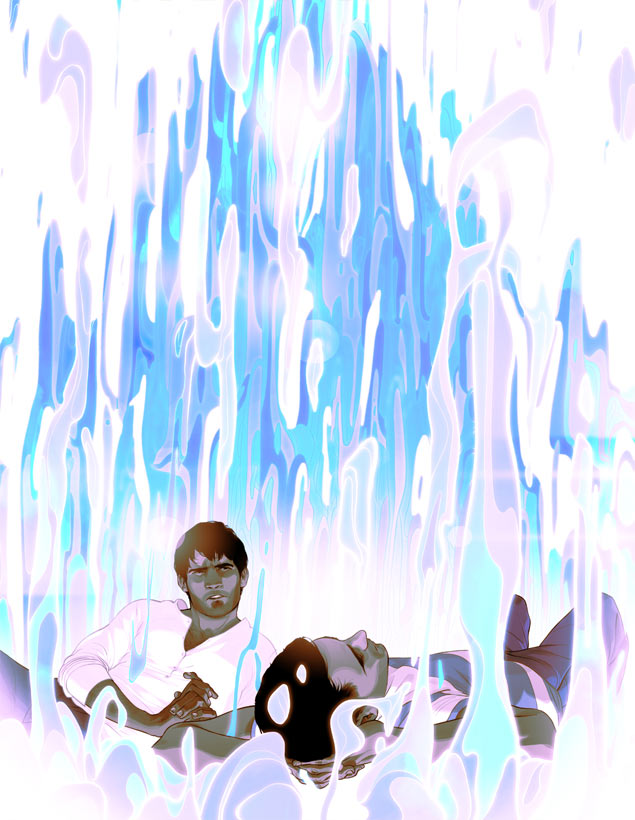

Copyright © 2017 by Sam J. Miller

Art copyright © 2017 by Goñi Montes

The phone controlled polymers were a very cool concept.

I’m glad the author and Otto acknowledged by the end that Trevor (?) was not actually acting like a good boyfriend with his controlling and judgmental stuff.

Great concept and I live the way the macro and micro stories reinforce each other.

I’m not convinced the polymer kaiju would be as big a menace as described though. Bombs might not work well, but it wouldn’t take the military long to get onto the idea of solvent weaponry. Electricity and heat would probably be effective too.

I liked this story a lot, mainly because of the interesting, complex, and nuanced characters. It also made me feel very uneasy, as it explores Otto’s and Trevor’s relation, with honesty and without holding back.

I am looking forward reading more by this author. Also a shout out to Goñi Montes for the beautiful cover.

Well, this was excellent. Probably my favorite short. I loved the dual storylines, and how Otto finally realized the truth.

I can’t believe only 4 comments, I just re-read this and was totally taken aback at how much deeper the story had become, how fascinating. The 1st time my attention was caught by the story itself, the 2nd by the nuanced development that added depth and dimensionality. I was left wondering if this was an intro to something longer?

Wow. Did not see that time jump coming or what happened in the interim, despite it being foreshadowed so nearly.

I suspect a lot of people stop reading before getting to that. Hence the lack of comments. Otto’s self-loathing, Trevor’s controlling nature and the self-absorption of the whole dinner party set the up the second part effectively, but makes the first part difficult reading. I found it hard to empathise with Otto’s murderous impulses in the second part as well.

But the mirrored themes of self-destruction in the micro and macro plots are well handled.

I guess this is my new favorite genre! “Vaguely Erotic With A Very Compelling Sci-fi Concept” – keeps your blood pumping and your brain enthralled!

This exploration of programmable matter was marvelous, Otto seeing Trevor’s betrayal of him hit hard, and I’m always happy to read a story that doesn’t mishandle queerness.

Although, I can’t help but think that companies would try anything to make people pay for those tons of downloads. “Pay 99 cents or your broom expires” or “Get premium models under this plan..!”

Malware might also manifest a camera in your teddy bear, eh?

Overall, a joy to read!

I find myself surprised and delighted that such thought-provoking and beautifully written erotica has finally found itself in the mainstream. At last!

Great story. Bitter complexity kept building, then it all tied together, and a healthy ending emerged.