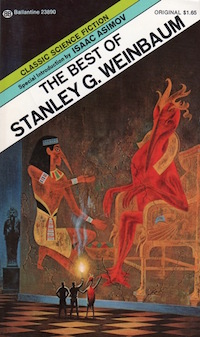

Sometimes, a story hits you like a ton of bricks, and you immediately resolve to look for more by that author. For me, “A Martian Odyssey,” by Stanley G. Weinbaum was one of those stories. I read it in an anthology I’d found at the library, but couldn’t find other books by him on the shelves. Years later, though, I came across a collection with his name on it and immediately shelled out $1.65 to purchase it. And then found out about Weinbaum’s untimely death, which explained why I couldn’t find any of his other works. It was soon apparent that he was not a “one-hit wonder,” as every story in the collection was worth reading.

In the mid-1930s, when Stanley Weinbaum started writing science fiction, the field was considered the pulpiest of pulp fiction. The stories were full of action and adventure, but thin on character, realism, and science rooted in reality. John Campbell was still a few years away from taking the editorial reins at Astounding Science Fiction and bringing respectability to the field. Weinbaum’s stories immediately stood out as different. His characters felt real and acted realistically. There was romance, but the women did not exist only as objects to be captured and/or rescued. The science was rooted in the latest developments, and thoughtfully applied. And most of all, the aliens were not simply bug-eyed monsters existing to invade the planet or threaten humanity. They felt real in the same way the human characters did—and yet seemed anything but human in the way they thought and acted.

In Weinbaum’s hands, a genre that was known for immaturity had grown up, but in a way that didn’t sacrifice any of the humor, fun, and adventure. You could read the stories for the sense of thrilling adventure alone, but those who wanted more found that as well. Unfortunately, Weinbaum barely had time to make an impact on the genre, as shortly after his first story appeared, he was dead.

About the Author

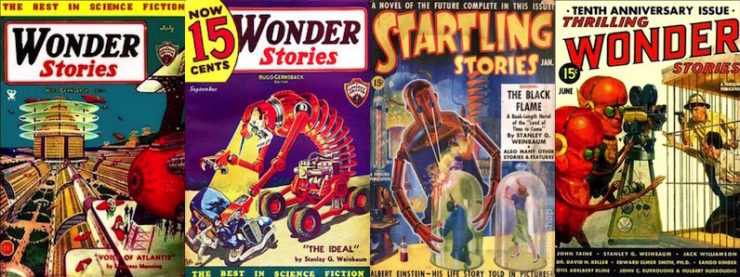

Stanley G. Weinbaum (1902-1935), was one of the greatest science fiction authors to emerge in the period between the two World Wars. An internet search reveals very little about his life; websites with information on the man tend to repeat the same basic facts. His greatest story, “A Martian Odyssey,” was printed in July of 1934, and only a year and a half later he was dead of lung cancer. He studied chemical engineering, then English, but did not graduate from college. Most of his stories were published in Wonder Stories or Astounding, and all of the science fiction works that appeared before his death were short stories. Under a pen name, he had also written a romance novel, and about half of his total output appeared only after his death. Longer works that later surfaced showed that he was also adept in novel writing. His work was very well received (to say the least), and his premature death viewed as a tragedy for the science fiction community.

Stanley G. Weinbaum (1902-1935), was one of the greatest science fiction authors to emerge in the period between the two World Wars. An internet search reveals very little about his life; websites with information on the man tend to repeat the same basic facts. His greatest story, “A Martian Odyssey,” was printed in July of 1934, and only a year and a half later he was dead of lung cancer. He studied chemical engineering, then English, but did not graduate from college. Most of his stories were published in Wonder Stories or Astounding, and all of the science fiction works that appeared before his death were short stories. Under a pen name, he had also written a romance novel, and about half of his total output appeared only after his death. Longer works that later surfaced showed that he was also adept in novel writing. His work was very well received (to say the least), and his premature death viewed as a tragedy for the science fiction community.

Testimonials

The Best of Stanley G. Weinbaum appeared in 1974 as the first volume of a “Best of…” series by Ballantine Books. In addition to bringing many of Weinbaum’s stories to the attention of a new audience, the volume gives us information not available from other sources in the two essays that serve as the introduction and the afterword. The first, “The Second Nova,” was written by Isaac Asimov. Asimov contends that there were three “novas” who burst on the science fiction field in its infancy, changing it forever. The first was E.E. Smith. The third nova was Robert Heinlein. And the second was Stanley G. Weinbaum, whose “Martian Odyssey” set the field on its ear with the quality of the writing and uniqueness of its alien creatures. Asimov argues that the tale had all of the qualities that people associate with the fiction Campbell became known for editing, and speculates that if Weinbaum had lived to produce more, the “Campbell revolution” that brought realism and humanism to SF might have instead been called the “Weinbaum revolution.”

The Best of Stanley G. Weinbaum appeared in 1974 as the first volume of a “Best of…” series by Ballantine Books. In addition to bringing many of Weinbaum’s stories to the attention of a new audience, the volume gives us information not available from other sources in the two essays that serve as the introduction and the afterword. The first, “The Second Nova,” was written by Isaac Asimov. Asimov contends that there were three “novas” who burst on the science fiction field in its infancy, changing it forever. The first was E.E. Smith. The third nova was Robert Heinlein. And the second was Stanley G. Weinbaum, whose “Martian Odyssey” set the field on its ear with the quality of the writing and uniqueness of its alien creatures. Asimov argues that the tale had all of the qualities that people associate with the fiction Campbell became known for editing, and speculates that if Weinbaum had lived to produce more, the “Campbell revolution” that brought realism and humanism to SF might have instead been called the “Weinbaum revolution.”

The essay that ends the anthology is “Stanley G. Weinbaum: A Personal Recollection,” by Robert Bloch—the same Robert Bloch who achieved fame as a writer in a wide range of genres, as well as working on TV and movie scripts (Bloch wrote the book that Hitchcock adapted as the movie Psycho, and also wrote the Hugo-winning tale “That Hell-Bound Train,” one of the finest stories ever penned). As a teenager, Bloch joined a Milwaukee-based writing group, the Fictioneers. Weinbaum, at 32 years of age, was already a member of the group. Despite that age difference, Bloch and Weinbaum became close friends. Bloch’s essay describes Weinbaum in glowing tones, not just as a writer, but as a gifted storyteller. He praises his empathy, his sense of brotherhood, and his sense of humor, all qualities that come through in his writing. Bloch describes Weinbaum continuing to spin out ideas right up until his death of from cancer, and ends by calling him a “charming, witty, gentle and gracious friend.”

The Best of Stanley G. Weinbaum

After Asimov’s initial essay, the book opens with Weinbaum’s masterpiece, “A Martian Odyssey,” which describes the first expedition to Mars by a four-man international crew. The Mars they land on is typical of stories of the time, a world with a barely breathable atmosphere, crisscrossed by canals, and marked by what appear to be the ruins of cities. The creatures the story describes, however, are anything but typical. Jarvis, missing for ten days, describes how he spent that time accompanied by a Martian called Tweel, a birdlike creature with the characteristics of both plant and animal, as tall as a human, who travels in massive leaps that end with his long beak embedded in the ground like an arrowhead. Jarvis rescues Tweel from the tentacles of a strange beast, and the two begin an odd and compelling friendship. They develop a pidgin language, and Jarvis realizes that Tweel is not only intelligent, but has a fair amount of scientific knowledge. In their travels, they discover a creature with a silicon-based biology, as well as a telepathic creature who lures its victims with scenes from their fondest dreams. They encounter a city of strange and hostile creatures, and Jarvis is rescued by one of his companions as Tweel leaps to safety and is lost. The story is fascinating, brimming with humor, and Tweel is at once likeable and incomprehensible.

The next story, “Valley of Dreams,” is a direct sequel to the first, and while it is good to meet our old friends again, the story suffers by repeating many of the same themes. The crew learns more about Tweel’s people and their efforts to keep the dying planet alive. In a decaying city, they find a mural that suggests that Tweel’s ancestors traveled to Earth and inspired the legend of the ancient Egyptian god Thoth. In the end, the crew gives Tweel’s people the secret of atomic energy, in the hopes that the technology can give the Martians the edge they need in their endeavor.

“The Adaptive Ultimate” is a horror story in the mold of the superhero origin stories that filled comic books in following decades. Two doctors inject a dying woman with a serum drawn from fruit flies, hoping to help her adapt to, and overcome, the disease that is killing her. She soon proves adaptable to any situation or surroundings, irresistible to men, and totally amoral in dealings with humans she now considers her inferiors. Fearing that she may soon rule the world, the doctors cleverly use their scientific knowledge to subdue her and return her to normal.

The tale “Parasite Planet” is set in the twilight zone that encircles a tidally-locked Venus, a zone teeming with aggressive plant and animal life. Weinbaum’s Venusians are every bit as interesting as his Martians. We meet “Ham” Hammond, who is collecting x’ixtchil spore pods, priceless because of their rejuvenating properties. Ham’s camp is destroyed by a mud spout, and as he escapes, he discovers the camp of Patricia Burlingame, a biologist who considers him a poacher. When a creature destroys her dwelling, the two of them set out toward safety, which they eventually find, along with love, emerging only after many twists and turns in their relationship. Patricia is refreshingly plucky and resourceful—Ham’s equal in every respect, which makes her meekness when they finally profess their love somewhat disappointing.

In “Pygmalion’s Spectacles,” a young man meets a scientist who has developed a device that immerses the user in another world. While the story does not use the term, Weinbaum outlined the concept of what we now call “virtual reality” years before the technology ever existed. The young man falls in love in that alternate world and, surprisingly, finds a way to pursue that love back in the real world.

“Shifting Seas” deals with climate change. A young American geologist barely escapes in his gyrocopter when the Pacific “Ring of Fire” cuts loose, destroying the Isthmus of Panama. This disrupts the Gulf Stream, and soon the nations of Europe are freezing and looking to evacuate. Other nations are not open to these plans, and before long war is looming. And, since our hero’s fiancée is the daughter of a British emissary, these events threaten his romantic life as well. Driven by hormones as much as altruism, he comes up with an idea that can restore the status quo, and love conquers all.

In “The Worlds of If, ” we meet young industrial heir Dixon Wells, who is perpetually late, and his former teacher, the comically and insufferably arrogant Professor Haskel van Manderpootz. Dick misses a passenger rocket to Russia, and finds that the Professor has developed a machine that allows a person to experience what would have happened had their life turned out differently. Dick uses the machine, and finds that, if he had not missed the rocket, he would have fallen in love with a woman during the journey. He is crushed until he realizes she is not listed among the dead after the ship crashes into the ocean. But then finds she also fell in love with someone during the rocket trip, someone who wasn’t him—he was too late again.

“The Mad Moon” is set on the Jovian moon Io. In the 1930s, there were theories which held that Jupiter might emit enough heat to make its moons habitable. Grant Calthorpe is an adventurer looking to harvest ferva leaves in the moon’s jungles, despite the threat of white fever. He sees a woman in evening dress, Miss Lee Neilan, daughter of the man he works for, and assumes she is a hallucination (and she assumes the same of him). But she actually wrecked her rocket plane while flying to a party. As is often the case in situations like this, the two of them survive many strange and menacing creatures until they are rescued, and fall in love in the process.

The story “Redemption Cairn” follows the adventures of Jack Sands—a rocket pilot whose reputation was ruined when he crashed on an expedition to Europa—who is then asked to pilot a rocket back to that site. He is partnered with female rocket pilot Claire Avery. The two of them dislike each other from the outset, although their adventures put them on a course toward true love. Jack finds there is a sinister secret behind this new expedition, but also a chance for redemption.

“The Ideal” (Wonder Stories, 1935) returns Dixon Wells and Professor van Manderpootz to the stage. This time, the professor has developed the “idealizator,” a machine that shows the viewer an idealized version of whatever is on their mind. Dixon naturally think of the ideal woman, and is delighted to find she is based on his early memories of an actual woman, whose daughter Denise is about his age. He and Denise hit it off until he shows her the machine; he leaves her with it and is late returning to check on her. She has used the machine to visualize the ultimate evil, and seeing his face on the heels of this horror, can no longer bear to look at him. Poor Dixon is too late once again.

In “The Lotus Eaters,” we again meet newlyweds Ham and Patricia Hammond. They are on a joint expedition to explore the night side of Venus. They discover wildly intelligent creatures with a collective mind, who learn English within a few hours. These intelligent plants are another of Weinbaum’s intriguing aliens, whose thought processes are described in a fascinating and compelling manner. But when Ham and Pat begin to fall into the passive mindset of the plant creatures, they encounter a threat more dangerous than any they have yet faced.

“Proteus Island” takes us back to Earth, to an unexplored South Sea island. The story is marred by a portrayal of Maori men as superstitious and ignorant, and by a racial slur uttered by the protagonist, a zoologist named Carver. The Maori men strand Carver on the island because of a taboo, and he finds that every plant and every animal on the island is different. He sees all sorts of odd and interesting creatures, and then a beautiful girl—but he wonders, in the midst of so much strangeness, if she is as human as she seems. The situation presents him with mystery after mystery, until Carver finally discovers the secret behind them: a scientist who had used the island as a laboratory for genetic engineering experiments. Again, Weinbaum delivers a tale far ahead of its time.

Final Thoughts

This collection makes it clear Weinbaum’s untimely death was indeed a tragic loss for lovers of science fiction. The summaries I have offered above cannot begin to capture the charm of his stories. His writing is smooth, his characters compelling and appealing, and underlying it all is a good-spirited worldview and sense of wit. His aliens are truly alien, and cleverly portrayed. While some of the science will set modern teeth on edge, the tales were solidly rooted in the knowledge available at the time they were written. And in predicting and speculating about future scientific issues like virtual reality, climate change, and genetic engineering, Weinbaum showed a knack for many scientific areas and disciplines.

As always, it is now your turn to have a say. I would imagine that because of the age of the stories, many of them might be available for reading on the internet, and if anyone has any idea how to find them, I would welcome your comments. And what are your thoughts on Weinbaum and his work? Were you as captivated by his stories as I was?

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.