Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

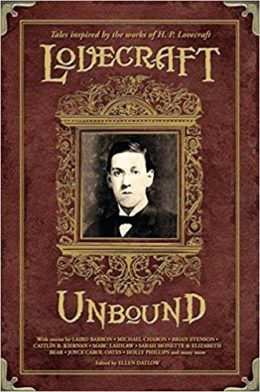

Today we’re looking at Marc Laidlaw’s “Leng,” first published in Ellen Datlow’s Lovecraft Unbound anthology in 2009. Spoilers ahead.

“No adventurer has ever followed lightly in the footsteps of a missing survey team, and today’s encounter in the Amari Café did little to relieve my anxiety.”

Summary

Being a selection from the “Expeditionary Notes of the Second Mycological Survey of the Leng Plateau Region,” a rather grandiose title given that Unnamed Narrator is a fungus enthusiast rather than a mycologist and his expedition consists of himself and guide Phupten. The “First Mycological Survey” consisted of Drs. (and spouses) Danielle Schurr and Heinrich Perry, who’ve gone missing.

In Thangyal, Tibet, narrator and Phupten visit Mr. Zhang, a restauranteur who befriended Danielle and Heinrich and tried to dissuade them from exploring Leng. The Chinese government issues no permits to visit the plateau, though Zhang won’t say why. Narrator risks sneaking in, lured by the exotic mushrooms on display in the Thangyal market, including the prized Cordycepssinensis or caterpillar fungus. This oddity overwinters in the body of a spore-inoculated caterpillar; in summer, it sprouts from its withered host like a single blade of grass, bearing fresh spores.

The only pass into Leng is guarded by Bu Gompa, a temple even older than the pre-Buddhist faith Bon-po. Its current priests, Buddhists of a sort, still guard Leng.

Beyond Thangyal, our “expedition” presses on with pack horses and Tibetan drivers. Narrator is surprised but pleased to discover that the two horse-drivers are as intrigued by mushrooms as he is. They understand (unlike most Westerners) that a fungus’s fruiting bodies are a tiny fraction of the mass hidden below ground.

Narrator and party reach Bu Gompa; the monks welcome them as if their expected. Besides the usual Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, the temple’s painted hangings show the “patron” of Leng’s original priests: “a ubiquitous shadow…amorphous, eyeless, mouthless, but not completely faceless.”

The horse-drivers make offerings at the temple shrines. Out of courtesy, narrator moves to do the same. Phupten draws him aside. Notice, this temple has no pictures of the Dalai Lama. That’s because he’s called their protector deity an unenlightened demon. Narrator asks why this doesn’t stop their companions

Before Phupten can answer, more monks arrive. One is Caucasian. He shocks narrator by announcing that he’s the missing mycologist Heinrich Perry!

Heinrich explains that the “First Survey” was never lost. On reaching Bu Ghompa, he decided to remain with the monks. Danielle went down to Leng and made discoveries of her own. Returning, she went into meditative retreat in a cave above the monastery.

Narrator’s sorry both his idols have retreated from field work into spiritualism, but who’s he to judge? Their loss increases his own determination to penetrate Leng’s mycological mysteries. But viewing the fabled plateau from a balcony, its mystic beauty overwhelms him: “It struck me as a dreamland, suspended in its own hallucination of itself, impervious to the senses.”

Before retiring, narrator drinks tea in which is steeped Cordyceps lengensis. Heinrich explains its host worm is called phowa bu, the Death or Transcendence Worm. In the true practitioner of phowa, a blister forms at the top of his head and a channel opens there just wide enough to hold a single stalk of grass—so the inoculated worm, with its Cordyceps fruiting body “antenna”, is the “emblem” of the sacred practice.

Um, okay. At least the tea helps narrator sleep well–until Phupten wakes him up to run for it. Their horse-driver/guides are joining the temple, he says. When they pass the main hall, the two are at the central altar. A veiled priest prods a fat gray lump that bathes them in smoke or…dust? The priest approaches narrator and pulls aside his veil. It’s Heinrich. He leads narrator outside, toward the caves. There’s a richer, deeper way of knowing than cataloging the contents of Leng, Heinrich says. Ask Danielle.

In the cave, a hunched-over woman mumbles unintelligibly. A single gray filament juts from her skull. He pulls, and the top of her skull comes off with it. No, her whole body explodes, like a kicked puffball fungus, filling the cave with spores. Narrator gasps, inhaling.

He flees toward Leng. Heinrich and the other monks let him go. Phupten wanders off into the sea of grass to sit motionless, like Danielle in the cave. Leng lures narrator. It “stretches out forever, and beneath its thin skin of grass and soil waits a presence vast and ancient but hardly unconscious…The twilight hour, the gate of dreams. All these would be all that is left of me, for all these things are Leng of the violet light.”

Narrator walks toward Phupten, crosses a threshold, tears a veil, beholds Leng, “spread to infinity before me, but it was bare and horrible, a squirming ocean beneath a graveled skin,” aspiring only to “spread, infect and feed.” He took one step too far. Stepping back has done no good. Leng compels him to write, to lure others. He prays you (any future reader of the notes) have not touched him. He prays the power has [notes end]

What’s Cyclopean: The adjective of the day—maybe the adjective of every day from now on—is “yak-fraught.” It’s only used once; it only needs to be used once.

The Degenerate Dutch: Leng is “almost completely bypassed by civilizing influences;” Narrator speculates extensively about why the Chinese avoid it amid their push to modernize Tibet. Narrator also mansplains mushrooms to people whose culture revolves around them, although to his credit he realizes his error quickly.

Mythos Making: The masked high priest of Leng confronts Randolph Carter in “Dream Quest of Unknown Kadath.” Lovecraft’s version probably wasn’t hiding the face of a fungus-possessed American tourist behind that yellow mask, but then you never know.

Libronomicon: Mycology, Leng, and the mycology of Leng are discussed in Schurr and Perry’s Fungi of Yunnan, Gallardo’s Folk and Lore of the Forbidden Plateau, Journals of the Eldwythe Expedition (which our humble narrator forgot to pack)

Madness Takes Its Toll: Too much enlightenment, too quickly—our narrator suspects even before learning for himself—can be “more than a weak mind could encompass.” “Were there not perhaps monks who, at the moment of insight, simply went mad?” Yep.

Anne’s Commentary

While leafing through Ellen Datlow’s Lovecraft Unbound anthology, I needed one word to bring me to a skidding halt at Marc Laidlaw’s “Leng,” and that word was “mycological.” Fungi? Mushrooms? Those endlessly fascinating things that suddenly sprout through leaf-mulched forest floors or bark-armored tree trunks or logs ripe for rotting? And a mycological expedition to Leng, that is, the high plateau of Tibet? Excuse me while I get some buttered tea. This cannot wait.

You may know the chestnut-scented saying that there are old mushroom hunters and bold mushroom hunters but no old bold mushroom hunters. I myself am a very nervous mushroom hunter. I will gladly stare at and poke and smell even the most gelatinous of fungi, but I will only eat the most innocuous of them, the common puffballs and the practically unmistakable Laetiporus or chicken-of-the-woods. The one you see below is Laetiporus cincinnatus, or the white-pored chicken. This specimen was growing from the roots of an ancient oak mere yards from Butler Hospital, where two Lovecrafts died, and less than a mile from Swan Point Cemetery where three Lovecrafts lie buried. Coincidence? I think not. (That’s my foot in the photo. I wear a size eleven shoe. This tells you how MASSIVE that chicken clump was.)

Laidlaw’s narrator strikes me as a fairly young mushroom enthusiast and an extremely bold one. However, he has the book-learning and field-experience of a much older shroomophile and so can confidently munch on what he picks along the way to Leng. Where boldness goads him too far is in compelling him to Leng in the first place, which he semi-acknowledges. Chasing seasoned explorers who’ve vanished, not the safest choice. Chasing them to one of the last truly isolated places on earth, forbidden by legend and a current government not known for coddling scofflaws? Because you’re a young bold so-far-unpoisoned mushroom hunter excited by all the fungus-riddled worms on display in the marketplace?

Oh, why the hell not. What could go wrong?

About the worms, or rather caterpillars. Gotta come back to them. Genus Cordyceps is a real thing. Cordycepssinensis (or Ophiocordycepssinensis) is a real species found in the mountains of Nepal and Tibet. It and its many relatives around the world are called entomopathogenic fungi for parasitizing the larvae of insects. C. or O. sinensis likes the ghost moth caterpillar; their vegetable-animal union is supposed to produce a perfect yin-yang balance prized by medical herbalists. Supposedly the fruiting body enhances energy, libido, brain performance, endurance and who knows what all. I wouldn’t be surprised if there are many valuable compounds in cordyceptine biochemisty, but since the raw fungus often contains arsenic and other heavy metals, I’m not eager to sprinkle handfuls of it on my salad.

I’m not eager to get close to any C. lengensis products either. Without knowing it, narrator observes a whole sea of its fruiting bodies when he looks out over the Leng plateau—that’s no prime grazing land. But what insect’s larvae does C. lengensis parasitize? The shriveled specimen in his tea gives him no clue, looking like nothing more than a shred of ginseng. Maybe that’s because C. lengensis’s host is too big to fit in a tea bowl. Maybe you just need a wee little snip of it. Off an ear, say. Because—because—its host is PEOPLE, you fools! People inhale the spores, they incubate the fungus, grow a grass-blade monoantenna**, then slowly become that awful gray eyeless and mouthless but not quite faceless grub in the temple hangings. Finally, properly poked, they sporulate and infect others!

The deliciousness of edible mushrooms aside, which a great many humans appreciate, fungi do cast some dark shadows across the human imagination. Lots of them pack deadly poison in their spongy tissues, as subtle assassins through the ages (and the ghosts of overbold mushroom hunters) can testify. Lots are saprophytes, living on dead and rotting things. This is a laudable biological niche, rationally speaking, but emotionally speaking, high ick factor. Lovecraft never fails to strew fungi liberally around his graveyards and decaying manses and transPlutonian planetscapes. Not to mention the dirt floor of the Shunned House basement. And the kinda-sorta Fungi from Yuggoth. As for those fungi that are outright aggressive, or pathogenic, if you will, there’s this story, which makes the real ruler of Leng not that iconic yellow-masked priest but its vast fungal underpinnings. Probably the yellow-masked priest is just another fruiting body? And most recently there’s a novel by David Walton, The Genius Plague, in which a fungal organism infects human hosts who gain in intelligence but may become its pawns rather than independent symbionts.

Maybe I don’t want mushrooms on my pizza after all? Aw, why not, I could use some mind expansion, make it double C. leng, please, hold the anchovies.

** Ah hah! The grass-like monoantenna is a dead giveaway! C. lengensis hosts are really avatars of Nyarlathotep, like everyone’s favorite platinum-haired alien Nyaruko!

Ruthanna’s Commentary

I’ve been listening recently to the Writing Excuses podcast, using their insights on structure and theme to prod my thinking on my own work. In their discussions of “elemental genre,” horror is the element where you know everything is going to go wrong, and can see the moment where a character’s logical (or at least true-to-self) choices lead inevitably to Certain Doom. “Leng” is… elemental.

The expedition itself, for a start, is a whole map marked “bad idea,” though Narrator can be forgiven for not being genre-savvy enough to realize this. He is, after all, a mycologist, and used to thinking of mushrooms as a source of academic interest and culinary delight, rather than eldritch horror beyond human ken. When I’m in my kitchen I tend to agree with him. My larder currently includes fresh portabellas and shitakes, as well as dried woods-ear and black trumpet. Certain Doom, you may imagine, is imminent next time I make an omelet. So the “attraction” half of this week’s attraction-repulsion tango was thoroughly persuasive for me, as I drooled over the garlicky yak-and-mushroom stew t.

Then there’s staying overnight at a heretical temple—which is, of course, unavoidable once you’ve decided to explore Leng. But if the Dalai Lama says a place is bad news, you should probably listen. Plus—if any religious organization seems to be really good at getting converts, just run. Definitely don’t talk to someone who can explain everything.

And if you do talk to someone who can explain everything, and they have a hole in their forehead with a tendril coming out of it… you guys, this is why we teach kids not to pull hair. You never know when the whole attached head might come off in a puff of infectious sporulation. I joke, but this is in the running for the single creepiest image I’ve encountered in our Reread, and the most likely to give me actual nightmares. “I knew I must not breathe… but of course I already had gasped.” Yeah, me too.

The whole thing is made worse because Laidlaw hasn’t made up the cordyceps—only this story’s particular variant. The tropical variety is better known as “that creepy fungus that mind-controls ants” or the “zombie ant fungus.” The slender reproductive stalk really does grow out of the ant’s head. This is me not watching any of the videos that show up in response to a web search, because some types of horrible wisdom really do challenge the bounds of sanity.

For Lovecraft, knowledge is double-edged—irresistable and soul-destroying. His narrators quest obsessively after answers, and shrink from them as soon as they arrive. This tension between attraction and repulsion can be more or less believable, and more or less exasperating for the reader. Here, it works. While Narrator is still immersed in the attraction of Leng’s mystery, he already hopes that others don’t follow in his footsteps—not because he thinks they’d get in trouble, but because he fears the mystery’s more thorough loss. The desire for others to avoid the place simply gets more desperate as attraction flips to repulsion. And yet, driven by the controlling fungus, he still writes. Presumably a lama will come down later to retrieve that diary, sending it out into the world as further bait. Much like Muir’s cave from a couple of weeks ago, or our speculation about the true source of the final narrative in “Hounds of Tindalos.”

As Laidlaw suggests in his afterward, it can be easy for Lovecraftian writers to focus on the more obvious aspects of the Mythos, missing the power of the vast fungal body beneath that surface. Perhaps we should all embroider “eschew arbitrary tentacles” on samplers to remind ourselves. Laidlaw falls prey to no such tentacles—this is a powerful Mythosian tale not because of the lingering resonance of Kadath, but because it captures perfectly the elemental loss of control that makes cosmic horror horrifying.

Next week, we’re off for the holiday(s) along with the rest of Tor.com. On our return, you’ll get a duo: Algernon Blackwood’s “The Willows” along with Nathan Carson and Sam Ford’s recent graphic adaptation.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots (available July 2018). Her neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Dreamwidth, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.