I’ve decided I need a theme for what’s left of June and July. Inspired by the Pride Month Storybundle and the recent publication of the latest Astreiant novel, that theme is going to be Melissa Scott.

Over the next few weeks, I’m going to be reading several of Melissa Scott’s novels for the first time, and writing about them here. Starting with The Kindly Ones, originally published by Baen Books in the late 1980s and recently reissued by the author as an ebook.

In Greek mythology, the Kindly Ones—the Εὐμενίδες—is a euphemism for the Furies, the goddesses who “take vengeance on anyone who would swear a false oath” (Hom. Il. 19.260), or those who commit gross impiety like a child who murders their parent, or a host who injures their guest. And often, they’re invisible to all but their target, who is driven mad. The Kindly Ones is the title of the third play of Aeschylus’ “Oresteia” trilogy (originally performed in 458 BCE), and these furious goddesses form a part of the action in a different ancient Athenian playwright’s take on the tragedy of the children of Atreus, Euripides’ Orestes. (And likely many more, but only a tiny fraction of ancient Greek drama has come down to us.)

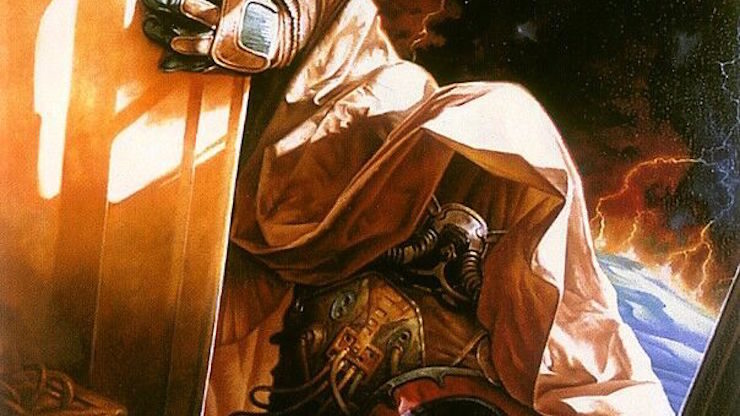

Buy the Book

The Kindly Ones

The title of Melissa Scott’s 1987 science fiction novel The Kindly Ones forbodes a reckoning, especially as it sets itself on two inhabited moons of the uninhabitable planet Agamemnon. Those moons are called Orestes and Electra, cold, harsh, and inhospitable. They were settled from a crash landing, and these unwilling colonists survived through the imposition of a strict social code. Life has grown a little easier: while at one point all violations of the code were punished with death, now in most cases only “social death” is required. Every Orestian city has a community of these “ghosts,” ostracised from family and community of origin, and none of the “living” may speak to them or acknowledge them in any way save through the office of an official “medium.” Alongside the ghosts are an intermediate class of people, self-selected outcasts to whom the Orestian social code doesn’t apply, who may speak to both the living and the ghosts, but who no longer have the protection of their original families, and who are looked down on by the rest of Orestian society.

Orestes and its smaller sister moon have been isolated from the galactic mainstream for a long time, but recently there’s been a lot more contact with the outside. Economic disruption plays into existing tensions in Orestian society, leading to feud and outright war—but when the highest families in Orestian society bend the code to their own purposes, an army of ghosts may use the code themselves.

The Kindly Ones follows three characters, all in some way outsides: Captain Leith Moraghan, retired from Peacekeeper Command and now flying a mailship that regularly calls at Orestes; Guil ex-Tamne, an Orestian outcast and pilot, and Moraghan’s friend; and Trey Maturin, a mediator, originally from off-planet, now working as a medium for one of Orestes’ most powerful families. Trey is, perhaps, the main character: we spend the most amount of time with him as he becomes more and more entangled and emotionally involved in Orestian politics—when a feud erupts, he becomes central to an Orestian war and its resolution.

His relationship with a male actor is well done, and their interactions highlight—as the novel’s title does, by reference to Aeschylus—the way in which narratives can be used and re-used. (The Kindly Ones doesn’t strongly emphasise this metacommentary, but it’s both interesting and there.) And to my delight, this is a very queer book: in addition to Trey, Moraghan and Guil are obviously lovers, though the novel never says so in as many words.

(Melissa Scott’s work really makes me wonder how I managed to go through the late nineties and early 2000s before I read a SFF novel that had an explicitly queer protagonist. Was there a backlash? Did no one publicise anything that had queerness in it? As far as I can tell, by the late 1990s, The Kindly Ones was already long out of print.)

With compelling characters, an atmospheric setting, and excellent pacing, The Kindly Ones is a fantastic novel. I really enjoyed it, and I thoroughly recommend it.

Liz Bourke is a cranky queer person who reads books. She holds a Ph.D in Classics from Trinity College, Dublin. Her first book, Sleeping With Monsters, a collection of reviews and criticism, was published in 2017 by Aqueduct Press. It was a finalist for the 2018 Locus Awards and is nominated for a Hugo Award in Best Related Work. Find her at her blog, where she’s been known to talk about even more books thanks to her Patreon supporters. Or find her at her Twitter. She supports the work of the Irish Refugee Council and the Abortion Rights Campaign.