In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

In the 1930s, from the thriving jungles of the pulp magazines, a new field appeared. A number of names were bandied about before one coalesced: science fiction. And at the same time, one magazine, Astounding, and one editor, John W. Campbell, emerged as the leading voice in that new field. You could easily call Campbell the father of the science fiction field as we know it today. And like all fathers, his influence evokes a whole gamut of emotions.

My own father started subscribing to Analog when he returned from Europe after World War II, and I started reading the magazine at the age of 10 or 11. In addition to finding much entertainment, my thinking about science, exploration, and many other subjects was shaped by what I read. And I quickly found my father also inherited many of his views, or had them validated, by John Campbell’s editorials. As I grew older, I began to see some of those views as narrow, but they continued to challenge my thinking. It was only later, through this collection, published in 1976, that I was exposed to Campbell as a writer and not just an editor.

About the Author

John W. Campbell (1910-1971) was a science fiction author and editor who had a profound effect on the genre. His fiction was rich in ideas, although his plots and prose often had the stiffness typical of the pulp fiction of the day. His most famous story was “Who Goes There?”, a gripping tale of terror published in 1938, which inspired three movies: 1951’s The Thing from Another World; 1982’s The Thing, directed by John Carpenter; and 2011’s prequel movie, also titled The Thing.

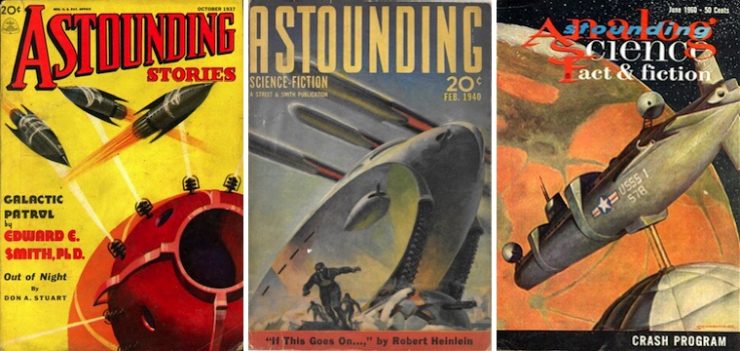

His real mark on the field was as an editor. He was selected to lead Astounding Stories magazine in 1937, and quickly changed its name to Astounding Science-Fiction, the first of a number of changes that eventually led to the name Analog Science Fiction and Fact. The first decade after he joined the magazine is sometimes referred to as the “Golden Age of Science Fiction,” as Astounding became the most influential science fiction magazine of its time. While other magazines like Thrilling Wonder Stories, Startling Stories, Planet Stories, and Captain Future continued to pump out lurid pulp stories of “scientifiction,” Campbell promoted a more thoughtful and mature approach. He bought the first science fiction stories from a number of future greats, including A. E. van Vogt, Robert A. Heinlein, and Theodore Sturgeon, and paid on acceptance to attract the top talent. Other authors who appeared in the magazine during the period included Isaac Asimov, L. Sprague de Camp, L. Ron Hubbard, Henry Kuttner, Murray Leinster, C. L. Moore, Lester del Rey, Clifford D. Simak, E. E. Smith, and Jack Williamson. Science fact columns were a regular part of the magazine, with contributors like L. Sprague de Camp, R. S. Richardson, and Willy Ley.

Campbell also established the fantasy magazine Unknown in 1939. While the magazine lasted only four years, it brought to fantasy the same rigor and attention to detail seen in Analog.

As the decades went on, Campbell continued to find strong writers for Analog, including Poul Anderson, Christopher Anvil, Hal Clement, Gordon R. Dickson, Harry Harrison, Frank Herbert, H. Beam Piper and Mack Reynolds. Campbell won eight Hugo awards for best editor, and would have no doubt won more if the award had been in existence in the earlier years of his tenure. Campbell continued to edit Analog until his death in 1971.

Each year since 1973, in Campbell’s memory, the John W. Campbell Memorial Award has been presented for best science fiction novel. The award was established by Harry Harrison and Brian Aldiss to honor Campbell’s contributions to science fiction, and to encourage the best from authors. The award is selected by a committee of science fiction authors.

Like many authors of his era, there are works by Campbell which have gone out of copyright, and are available to read on the internet, like these stories, available via Project Gutenberg.

Father Complex

I always thought of my father as a typical Analog reader, an assumption validated when we later started attending science fiction conventions together. My father was bespectacled and shy, worked in research and development for an aerospace firm, and always wore a pocket protector filled with colored pens and pencils, and a miniature slide rule he used for rough calculations. He loved to challenge me intellectually, enjoying a good thoughtful discussion.

We are all shaped by our parents, sometimes by their presence or absence. We model ourselves on them, adopting their strengths and their weaknesses. And as we emulate those strengths, we spend years fighting to avoid copying those weaknesses. The term “father complex” describes the unconscious reaction we have to the idea of a father, which can be either positive or negative, or both, depending on our experience. While I never met the man, John Campbell and his ideas were often intertwined with the discussions I had with my own father. So I naturally grew to think of Campbell as a father figure for the field of science fiction.

Under Campbell’s direction, Analog exhibited a strong “house style.” It celebrated independence, logic and self-reliance, with its typical protagonist being referred to as the “competent man.” The human race was usually portrayed as more clever and inventive than alien races, even those who had superior technology. And when I later read a collection of Campbell’s letters, it was apparent he kept a heavy hand on the helm, insisting writers conform to his notions about the way the world should work. Campbell wanted characters that acted like real people, instead of the cardboard characters of the pulp age (although the fact those real people were almost always engineers or technocrats became a new cliché of its own). He also insisted on rigor in the science that was portrayed. You could present science and technology beyond what we know today, but you had to do it in a consistent and logical manner, and not in conflict with accepted scientific principles. If pulp science fiction tales were driven by the Freudian id or emotions, the stories of Analog were driven by the ego, super-ego, and logic. Campbell almost single-handedly dragged the science fiction field into being a more respectable genre, and when new magazines like Galaxy Science Fiction and The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction emerged in the 1950s, they emulated this more mature model rather than the pulp sensibilities of the past.

Campbell, however, was not without his flaws and foibles. Like many in his era, Campbell displayed an insensitivity on racial issues. In his essay “Racism and Science Fiction,” Samuel R. Delany tells how Campbell rejected an offer to serialize the novel Nova, “with a note and phone call to my agent explaining that he didn’t feel his readership would be able to relate to a black main character.” I remember reading Campbell’s editorials on racial problems in the 1960s, and being struck by the implicit assumption a person of color would not be reading he had written.

Campbell’s Analog was overwhelmingly dominated by men, both male writers, and male protagonists. Off the top of my head, I can think of only two female leading protagonists I encountered in Campbell’s Analog: the linguist in H. Beam Piper’s “Omnilingual,” and Telzey Amberdon, the telepath whose adventures were written by James H. Schmitz. I know there were more, but they were few and far between.

Campbell also developed a penchant for ideas from the fringes of science, and even pseudo-science. He was fascinated by telepathy, and the idea human evolution would lead to the ability of humans to control their environment with their thoughts. He also was an early supporter of “dianetics,” the ideas of L. Ron Hubbard that eventually led to the establishment of the religion of Scientology. Despite growing evidence to the contrary, he long argued against the dangers of smoking. He promoted a kind of perpetual motion device known as the “Dean Drive.”

Campbell was very sure of himself and his conclusions, valuing ideas more than relationships, and parted company with many authors over the years. To say his politics were conservative would be an understatement. He could be a very polarizing figure.

While Campbell quite rightly deserves respect and admiration for his positive impact on the field of science fiction, we cannot ignore the fact he also introduced attitudes the field has spent decades outgrowing. Like our relationships with our parents, the field’s relationship with John Campbell is complex.

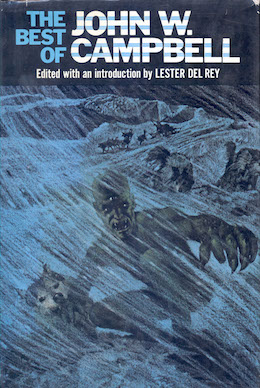

The Best of John W. Campbell

In his introduction, author and editor Lester del Rey divides Campbell’s career into three phases: the author of straight-ahead pulp adventure stories, the author of more thoughtful and moody stories, and finally the editor of Analog. He only includes one story, “The Last Evolution,” from the first phase, a story of alien invasion where humanity is destroyed, but succeeded by our robotic children. While much of the story is predictable, the humans meet the invading dreadnaughts not with mighty ships of their own, but with tiny autonomous drones, an idea far ahead of its time. And the idea of robots as intelligent successors was also unique for the time.

In his introduction, author and editor Lester del Rey divides Campbell’s career into three phases: the author of straight-ahead pulp adventure stories, the author of more thoughtful and moody stories, and finally the editor of Analog. He only includes one story, “The Last Evolution,” from the first phase, a story of alien invasion where humanity is destroyed, but succeeded by our robotic children. While much of the story is predictable, the humans meet the invading dreadnaughts not with mighty ships of their own, but with tiny autonomous drones, an idea far ahead of its time. And the idea of robots as intelligent successors was also unique for the time.

The second story, “Twilight,” is packed with gloomy ideas about a human race that has lost its drive and curiosity, and hints at the evolution of robots. While the ideas are compelling, the format is infuriating to a modern reader used to authors “showing” instead of “telling.” The story is structured as one man telling another about a story he heard from a hitchhiker who turned out to be a time traveler, removing the reader from the action by several layers.

The next three stories together form a trilogy. The first, “The Machine,” portrays a humanity coddled by a powerful machine that decides its influence is more negative than positive, and turns itself off. Only a few machine-picked survivors are left to rebuild civilization. The second story, “The Invaders,” describes how an alien race, the Tharoo, conquers the Earth, and begins to use eugenics to build the human race into better servants. And in the third story, “Rebellion,” the humans take the eugenic principles of the alien invaders, and breed into themselves the capabilities needed to exile the alien invaders. These stories were written in the 1930s, and I doubt they would have been written in quite the same manner after World War II, when Nazi racism and genocide discredited the very idea of human eugenics.

“Blindness” is a sardonic story about a gifted researcher and his assistant who exile themselves to a close orbit around the sun for three years to uncover the secrets of atomic power. But upon their return, they find their sacrifices are not valued as they had expected. “Elimination,” is another story with a twist, when the ability to predict the future becomes a curse rather than a blessing. In “Forgetfulness,” explorers find a planet they think has fallen from the heights of civilization, only to find the aliens have forgotten less than they thought.

The following two stories represent halves of what is essentially a short novel. In the first, “Out of Night,” an alien matriarchy, the Sarn, has conquered Earth, and proposes converting the human race into a matriarchy as well, killing males so they make up a smaller portion of the human population. The Sarn attempt to play human factions against each other, but in the end, the humans convince them a human god, the Aesir, has arisen to oppose them, and they back down. The Aesir is actually a hoax, which uses a telepathy and a new scientific development to shield an ordinary man from their attacks. The next story, “Cloak of Aesir,” shows the Sarn beginning to bicker among themselves, and fail in their attempts to subjugate the humans. In the end, the humans use their growing mental powers and the threat of Aesir to sow doubts among the Sarn, leading to their eventual retreat.

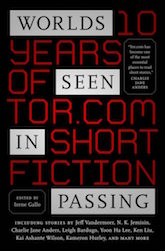

Buy the Book

Worlds Seen in Passing

The final story in the collection, “Who Goes There?”, is clearly Campbell’s finest authorial work, a taut and gripping tale of suspense. The difference in style between the first story in the collection and this one is like night and day. A polar expedition finds an alien creature frozen into the ice, and in trying to thaw its crashed spaceship, accidentally destroy it. They decide to thaw the creature for research, which leads to disastrous results. Not only has the creature survived being frozen, but it has the ability to take over and mimic other living things. The researchers try various methods of determining which of them have been replaced by the alien, encountering shocking deaths and setbacks at every turn. Only a few will survive, and only by the skin of their teeth. It is obvious why this story has since appeared in so many collections, and inspired numerous movie versions.

One of Campbell’s editorial essays is included: “Space for Industry.” It explains how, if the human race expands into the solar system, its efforts will not focus on the planets, and resources trapped at the bottom of gravity wells, but instead on asteroids and other small objects that can be more easily exploited. But it also states “…any engineering development of space implies a non-rocket space drive.” So, since rockets are all we have, and indeed, all we may ever have, in the eyes of the father of science fiction, a large-scale move of humanity into space may not be likely.

The final entry in the anthology, “Postscriptum,” is an essay by Mrs. Campbell, written after his death. It gives us a glimpse into the human side of a man known to most only through his work, a loving husband and father missed by those he left behind.

Final Thoughts

John Campbell’s influence on the field of science fiction was huge. His editorial work brought the field a maturity and respectability that had been lacking. And his writing, as exemplified by the works in this collection, shows the growth and transformation of the field from its pulp fiction origins. At the same time, he left a complex legacy.

And now I turn the floor over to you. Have you read this collection, or any of Campbell’s other tales? Have you, like me, been a reader of Analog? What are your thoughts on the man, his work, and his impact on science fiction?

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.

I have read quite a few Campbell stories including those reviewed here (though not in this specific collection). I prefer Don A. Stuart to John W. Campbell and generally find his fiction more academically interesting than literarily engaging. Campbell has always been a figure of science fiction’s past to me and one to treat with great ambivalence: I liked many of the writers he developed but hated his peddling of junk science and contrarian posturing. I also think he stayed at least a decade too long as Analog editor: not all fatherly advice, however warmly intended, is applicable to the next generation and Ben Bova’s takeover was long past time.

In one of those odd coincidences, the piece I am working on mentions the Best of Campbell in passing. May I add a link to your piece?

I think you summarized my opinion in the article: Campbell was a talented writer and a great editor. The latter dominates the former.

In addition to his by-current-standards abominable racism (Campbell lived through the Presidency of hideous racist Woodrow Wilson), SchuylerH has correctly pointed out that Campbell seemingly lacked the ability to distinguish between real science and absurd anti-science.

I try not to comment on the social issues as I have always thought it unfair to hold a 1940’s author to 2018 social standards. I have read his work both as Campbell and as Stuart; I have a fondness for Classic (not modern) space opera, and his Arcot-Wade-Morey books run a close second to Skylark (less so compared to Lensman). I did read Analog back in the day (probably post-Campbell) and I have read many of the authors he edited and mentored (and most of them were very grateful).

Again, on the basis of his writing I think he was very good. On the basis of his editing he gets full marks for the time/mixed marks for today. Joe Bob says “check him out.”

I’m a regular over at the Galactic Journey, where it’s always 55 years ago, and every month when Analog comes around, I tell myself not to read Campbell’s editorial, and all too often I fail to heed my own advice. They read as though handed down from on high and he brooks no contradiction. And yet they are full not only of the pseudoscience already mentioned (including an astrological weather forecast!), but also a number of logical fallacies exacerbated by his stubbornness. In a lot of ways, he’s the precursor of Internet edgelords who delight in “playing devil’s advocate” and “just asking questions”. His argument against serializing Nova is absurd, given that he had published Mack Reynold’s “Black Man’s Burden” in 1961/82 and it was rather well received.

His influence as an editor is unassailable. Science fiction would not be where it is without him, might not even still exist as a genre in its own right. But he’s deeply uncomfortable. A bit like your horribly racist grandfather, who taught you lots of wonderful things when you were a kid, but who you can’t let anybody outside the family actually meet.

John W. Campbell as “edgelord” (a more pungent term comes to mind) makes sense as an insight!

@2 By all means, James, feel free to link to the article. I always look forward to your articles.

Did Campbell ever knowingly buy a story from a black person?

Thank you! Interestingly, Campbell isn’t the most right wing author mentioned in the upcoming piece.

I always liked the urban legend about Campbell initiating/publishing Cleve Cartmill’s “Deadline” in 1944 and getting a visit from the government because of its description of the atomic bomb. I never really knew if it was true or not (or which parts were true) but that didn’t matter to me. I just liked the idea of a science fiction story hewing so close to reality that it spooked the government.

I don’t know enough to comment I will read more and and get back to you all

I like John Campbell but I have to disagree. I still feel Jules Verne is the father of modern sci-fi. Many of the things he postulated in his stories have come true like space travel and submarines. IMO anyway.

I always thought that the mother of Science Fiction was Mary Shelley. A lot of the novel structure and power of science came from there. The guys from Extra Credits made a video about it:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DnSmGFmP8qU

@11, @12 I will freely admit that my thoughts about Campbell being the father of SF are very subjective, and tied to the timing of my own introduction to the field. I can see arguments in favor of both Verne and Shelley as parents of SF, especially Verne. If anyone has other thoughts on who might be worthy of consideration as a parent of SF, I’d be interested in hearing them. In addition to discussing Campbell, of course.

@9: I recall “Deadline” was a case of Campbell writing a story by proxy to get a reaction. The story is atypical for Cartmill: Campbell apparently primed him with large amounts of publicly available material on atomic weapons (which was later his get-out clause when questions were asked). See also Heinlein’s Sixth Column and Godwin’s “The Cold Equations”.

@13: Lucian of Samosata!

@james:

That’s a good question, but then you have to ask how many writers of color there were at all during his tenure. I don’t know of any besides Delany, which certainly doesn’t mean there weren’t any.

As to Campbell as the father of modern science fiction, I think that’s stretching things a bit far. He certainly helped shape it and bring out of the Pulp Era, but he was building on something that was already there. More like Newton’s standing on the shoulders of giants. Father, no. More like its elementary or middle school teacher. He got it ready for what came after, but he didn’t handle its further maturation very well. (Much like he seems to have had problems with the way science itself changed even before the War.) He had a transformative vision, but he got locked into it and couldn’t really see beyond it to the next transformation.

Instead of suggesting Campbell as the father of modern science fiction, I would consider him one of the wet nurses (along with such people as Frederick Pohl and Hugo Gernsback, among others). You can have one father, but plenty of wet nurses, as needed.

@16 You make a good point, although I chuckle when thinking about how Campbell might react to being called “The Wet Nurse of Science Fiction.”

Mary Shelly is DEFINITELY the creator of science fiction.

This is a really interesting piece – in high school I took a sci fi class, and in college I was part of a group that studied/analyzed old pulp sci fi as part of an initiative so I have some passing knowledge. And I think you capture here the conflicting feelings that arise when looking back at authority figures who were flawed and products of their time.

The only way to judge Campbell is to look at what science fiction was like before he took over Astounding and what it was like after. He was a huge influence on everything that came after. I can also remember his monthly column, “Brass Tacks” IIRC, where among other things he discussed the merits of various methods of dowsing. One thing he did do was raise the quality of the writing. Science fiction changed for the better because of him. He did a lot of things wrong too but he did some things right.

I have this book (with a different cover from the one pictured) but I’m not sure if I ever read it. Some of the stories you mention sound familiar, while others don’t ring any bells. Del Rey/Ballantine published a series of “Best of…” books (Edmund Hamilton, C.L. Moore, Fritz Leiber, etc.) back in the 70s, of which I have about a dozen; some read, some not. I will definitely have to read (or reread) this one soon.

I remember reading a comment from Asimov that he decided to not introduce aliens in his stories because, being published by Campbell, he would had to treat them in a way he was uncomfortable with.

Also, apart for the already pointed racist and pseudoscience stuff, I remember from his Aarn Munro novels, he liked genocide as a solution to problems a bit too much… although never as much as EESmith, admittedly.

Coincidentally, I just happened to read Sam Moskowitz’s profile of Campbell the writer in the August, 1963 issue of Amazing. He talks about Campbell’s upbringing, and it shed some light on his personality. His father was very authoritarian, and teenage John would have to resort to logical tricks and traps in order to obtain permission to do things. It’s the sort of thing you see him doing in his editorials that led me to make that “edgelord” comment upthread.

I see Campbell as being not so much the father of American genre science fiction (for that’s arguably the old hack the WSFS named the award after) as a vital catalyst in the reaction for transmuting pulp into gold. Much of the top talent from the early days of Astounding consisted of authors who were already taking science fiction seriously, among them contributors of “thought variant” stories in F. Orlin Tremaine’s tenure. Campbell was able to bring them together and distribute their work to a wider and more mature audience through a slickly produced magazine, then use these draws to introduce new authors amenable to working in his house style.

The question of the progenitor of science fiction (assuming that such an entity ever existed) is quite irresolvable as it amounts to “which author wrote the first work I would recognise as science fiction”.

@22: The exception being “Blind Alley”.

@16 LouW I definitely also believe you have to bring in Gernsback as well. Pohl I think became an editor after SF had already built up a certain style and number of conventions, mostly because of Campbell’s influence.

I think of John Campbell as being the most influential SF editor ever, and one that pushed SF in the direction it needed to catch on as something more than niche pulp. But as a writer? Contrary to other posters above, I don’t think I’ve ever read anything of his I really enjoy except maybe Who Goes There. The Arcot stories are certainly nowhere near as entertaining as Doc Smith’s Skylark stuff.

@9: See http://blog.nuclearsecrecy.com/2014/03/07/death-dust-1941/ for information about the Campbell FBI incident (with https://web.archive.org/web/20130618175748/http://www.asimovs.com/_issue_0310/ref.shtml and https://web.archive.org/web/20141006183638/http://www.asimovs.com/_issue_0311/ref2.shtml for more).

@25: I liked the Arcot stories when I was a teen. I think that Harrison’s “Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers” is as much a parody of Campbell as it is of Smith.

I think it’s much more defensible (and accurate) to cite Campbell as “the father of modern science fiction.”

@21 There are actually two “The Best of John W. Campbell” anthologies out there; a British one with an introduction by James Blish, and the one I reviewed, edited by Lester del Rey (and they contain different stories). The book also appeared as part of Del Rey Books “Best of” series, but I think that is simply the del Rey edited version with another cover in paperback form. There was also a “John W. Campbell Anthology” with different contents.

Father of American SF, maybe. American post-pulp-but-before-galaxy-and-F&SF SF.

The absence of a particular name on the list of parents of sf gives me an idea for a piece, a somewhat overlooked but interesting classic…

@29 James Davis Nicoll I defer to you regarding SF history, but wouldn’t you say that Galaxy and F&SF were in part a reaction to Astounding, and maybe also taking advantage of the increased market and interest that Astounding had created, by moving into niches where Campbell was not interested? I tend to think that Astounding also discovered and nurtured many talents that went on to later write for Galaxy and F&SF.

Actually, now that I think of it, I’m not sure where I would place Amazing in this family tree. I haven’t read enough stories from it (that I know of) to have any strong opinion.

@26: Thank you for the links.

@30: Amazing’s tone and quality has varied extensively over its long run: I think Howard Browne’s Amazing would be the most Campbellian incarnation (at least, when he had the budget for it).

@31: No problem.

@13 AlanBrown: I’d submit H G Wells as a candidate. Verne and Wells were how I got hooked – Twenty Thousand Leagues and Time Machine were my first fixes of science fiction.

wrt parenting: did anyone before Campbell coach authors as much as he did? He was legendary for long letters dissecting submissions that he thought had promise but weren’t publishable as they were, and even for coaching and nudging authors in extending their universes. E.g., Asimov credited Campbell with pointing out the 3 Laws of Robotics as implicit in the first robot story, and McCaffrey spoke of him saying (summarized) “And?” every time she added a facet to Pern. Where Shelley, Verne, Wells, etc. set examples, he in effect parented much of a generation of authors. IIUC, this coaching became more and more tyrannical as he aged, and there were many authors he could do nothing for.

I would have sworn I made a comment re Campbell’s 1939 classic, Cloak of Aesir .

Did it get lost in the spam bucket? And I see I’ve never read (if memory serves) its 1937 prequel, “Out of Night.” Except, erm, I own that collection. Should dig it out. It’s a worthy one: http://www.isfdb.org/cgi-bin/pl.cgi?449232

Along with Shelley, Verne, and Wells — science fiction AND the magazines would be entirely different today were it not for the hyper mercurial John W. Campbell.

I am rather shocked to see no reference to this upcoming book

https://www.amazon.com/Astounding-Campbell-Heinlein-Hubbard-Science-ebook/dp/B074M6QRMP/

Astounding: John W. Campbell, Isaac Asimov, Robert A. Heinlein, L. Ron Hubbard, and the Golden Age of Science Fiction

by Alec Nevala-Lee

I never subscribed to Astounding/Analog — I was a Galaxy man — but I cut my teeth on reprints of the great anthologies of the late Forties and early Fifties, with copyright pages that were wall-to-wall “Street & Smith”.

“In his essay ‘Racism and Science Fiction,’ Samuel R. Delany tells how Campbell rejected an offer to serialize the novel Nova, ‘with a note and phone call to my agent explaining that he didn’t feel his readership would be able to relate to a black main character.’”

But @5/DemetriosX points out:

“His argument against serializing Nova is absurd, given that he had published Mack Reynold’s ‘Black Man’s Burden’ … and it was rather well received.”

To me, it sounds like the black protagonist explanation was a story told to Delany by his agent. The real reason may have been that Campbell regarded Nova as weird stuff his readers wouldn’t like (which is my recollection of the book). While Reynolds was a terrific storyteller in a more traditional sense.

In an early-Fifties corporate history of Street & Smith, it’s noted that the Campbell Astounding sold particularly well in Harlem, though the reason is unclear.

As well as establishing the John W. Campbell Memorial Award, Harry Harrison edited a tribute anthology intended as a last classic issue of Campbell’s Astounding:

Thought those reading this thread would be interested: at Worldcon there will be a panel, “The Astounding John W. Campbell, Jr.” Among the speakers will be Robert Silverberg, Joe Haldeman, and his successor Stanley Schmidt.

Ben Bova was Campbell’s immediate successor. Schmidt didn’t take over until towards the end of the 1970s.

Interesting thread I was asked by my present publisher, AbsolutelyAmazingeBooks.com, to write an introduction to some of Campbell’s earliest pulp fiction tales, and found them enjoyable. The volume still is up for sale on Amazon, (Modest plug there.) I was extremely fortunate early in life to encounter Campbell. He purchased my first novel within a month of my submitting it, at 90,000 words–and then went ahead and encouraged me to add another 30,000 words. I had feared writing much above 90 as a brand-new writer. He essentially said nonsense, the story is too good, let it roll. I submitted a first (additional) chapter. He said okay you’ve got it, keep writing and send it when you’re done. He never asked me what color my skin was or how old I was, just “where the hell have you been hiding?” Then he “sold” it to Doubleday for hardback publication with one phone call. That’s the influence he wielded. When I signed my Doubleday contract and my newspaper managing editor witnessed it, that was the day I was promoted from copy boy to reporter, setting my newspaper career in motion. All attributable to Campbell. Never met the man, though we exchanged numerous letters. He always–always–opened his letters with “Dear Mr. Burkett.” Which impressed a callow youth no end. Now I am older than he was when he died, and probably a curmudgeon. But all this revisionist nonsense about him reminds me of how we used to make fun of the Soviet Union for “vanishing” their heros/leaders when the Politburo winds shifted, and were constantly rewriting history. Campbell was the first person to suggest to me that before I was dead I’d see Russia acting more like America, and America becoming more totalitarian. The first part was sort of true after the Evil Empire collapsed, when the Wild Wild East erupted. But Campbell’s prediction failed because he did not envision an individual like the KGB thug who is rebuilding the Iron Curtain. He should have–Ike Asimov, after all, featured “The Mule” as a mutant interrupting the flow of Harry Seldon’s foundation and empire. Campbell’s place in literary history should be secure if there is any justice. But as Niven coined, “TANJ”

@41 — You must be referring to Sleeping Planet, one of my favorites from the Sixties.

As extensively discussed upthread, no one denies Campbell’s influence or the many writers whose careers he launched or boosted (to use a space metaphor). That doesn’t mean people have to be comfortable with his (by current standards) sexism, for instance.

As a science guy, I have always been put off by his habit of promoting horrible nonsense like the Dean Drive, Dianetics, and psychotronics.

@43 — The tragedy of John W. Campbell, as I see it, is that after a certain point he was not satisfied to be science fiction’s leading editor.

He wanted to, er, midwife a scientific revolution; thus the excursions into pseudoscience.

Failing that, he could at least be the courageous iconoclast who tells truth to power; thus some of his more extravagant and unpopular positions.

Another way of putting it is that he constantly dug smaller and smaller ponds to be the bigger and bigger frog in.

Of course, some positions he took that sound outlandish to 21st century ears were the “settled science” of the time, or views then held by a majority of educated people; e.g., eugenics