My foray through Lois McMaster Bujold’s backlist on my site—a foray nowhere near as detailed as Ellen Cheeseman-Meyer’s ongoing reread—reached Komarr recently. One of the elements of the setting impressed me: Bujold’s handling of the centuries-long effort to terraform the planet.

Terraforming is, of course, the hypothesized art of converting an uninhabitable rock into a habitable world. Jack Williamson coined the term in his Seetee-related short story, “Collision Orbit”, published under the pen name Will Stewart in the July, 1942 issue of Astounding Magazine. While Williamson invokes non-existent super-science in order to make the task seem doable, he probably felt confident that terraforming would someday make sense. In the short run, we have seen humans shaping the Earth. In the long run—well, Earth was once an anoxic wasteland. Eons of life shaped it into a habitable planet. Williamson suspected that humans could imitate that process elsewhere…and make it happen in centuries rather than eons. Perhaps in even less time!

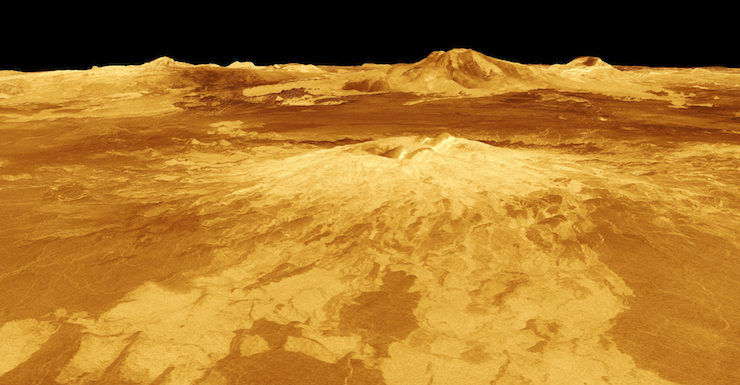

Other SF authors picked up the notion and ran with it. It had become clear that Mars and Venus were hellworlds, not the near-Earths of earlier planetary romances. Perhaps the planetary romance could be recuperated if Mars and Venus could be terraformed? And if we made it out of the solar system and found a bunch of new inhospitable planets… well, we could fix those, too.

Back in the 1970s, SF fans could read reassuring articles like Jerry Pournelle’s “The Big Rain,” which proposed terraforming Venus. Invest a hundred billion dollars (half a trillion in modern dollars) and wait a couple of decades. Voila! A habitable planet. We’d be stupid not to do it!

Of course, it’s never as easy in real life as it is in the SF magazines, which is why pretty much none of the Disco Era predictions of crewed space exploration panned out. Though they did produce some pretty art.

Venus can’t be terraformed as easily as Pournelle supposed, in part because he was drawing on a 1961 paper by Carl Sagan—by 1975 it was clear that Sagan had underestimated the extreme hellaciousness of Venus. Also, Pournelle’s estimate that it would take twenty years to do the job turned out to be, um, a smidge too optimistic. Even if all the sunlight hitting Venus could be used to crack carbon dioxide, it would take much, much longer than twenty years to do all the cracking necessary1. Algae isn’t 100% efficient. The process would sputter to a stop long before Venus became the planet-sized bomb I describe in the footnote below.

This should not be surprising. After all, it took well over two billion years for oxygen-producing organisms to produce a breathable atmosphere on Earth. Granted, nature wasn’t trying to produce a breathable atmosphere. It just sort of wobbled in that direction over billions of years. Directed effort should—well, might—be able to knock a few zeroes off that time frame. Lamentably, “incredibly fast on a geological scale” still translates into pretty goddamn slow as humans measure time2.

Komarr—remember I mentioned Komarr at the beginning?—acknowledges the time issue. Komarr is a lot closer to being habitable than any world in our solar system, but the people who settled it have invested vast sums as well as centuries of effort and the place is still far from being anywhere close to Earth Mark II. Or even Leigh Brackett’s Mars Mark II. It’s even possible that Komarr will never be successfully terraformed, and that better uses for the money will be found long before Komarr ever gets close to being as pleasant as Precambrian Earth.

Although all too many SF authors handwave fast, easy terraforming, Bujold isn’t alone in recognizing the scale of the problem.

Williamson’s aforementioned “Collision Orbit” only mentions terraforming in passing, but it’s clear from passages like—

Pallas, capital of all the Mandate, was not yet completely terraformed — although the city and a score of mining centers had their own paragravity units a few miles beneath the surface, there was as yet no peegee installation at the center of gravity.

—that despite being armed with super-scientific paragravity, transforming small worlds into living planets is a monumental task even for governments.

Walter M. Miller, Jr.’s 3 “Crucifixus Etiam” embraces the magnitude of the effort to turn an implausibly benign Mars4) into a new home for humans. He imagines this as a sink for the economic surplus that might otherwise undermine the global economy. It’s essentially Europe’s cathedral projects re-imagined on a vastly greater stage: a project that will take eight centuries.

Pamela Sargent’s Venus trilogy (Venus of Dreams, Venus of Shadows, and Venus’ Children) imagines a near-magic technology that can deal with Venus’ spin (or lack thereof5). The author does acknowledge that even with super-science, the project would be the work of generations, and the people who set the effort in motion would not live to see project’s end.

If one consults an actual scientist (using Martyn Fogg’s Terraforming: Engineering Planetary Environments, for example), one learns that the time scales required for the creation of Garden Worlds6 might range from “The Time Elapsed Since the Invention of Beer” to “The Average Lifespan of a Vertebrate Species.” Depressing, yeah? Has any organized human group effort lasted as long as The Time Elapsed Since the Invention of Beer? Certainly not for The Average Lifespan of a Vertebrate Species.

One unorganized human effort, Australian Aboriginal Fire-Stick Farming (which reshaped an entire continent’s ecology), appears to be a serious contender for The Time Elapsed Since the Invention of Beer, if not longer. Perhaps that should give us hope. And perhaps it’s not unreasonable for SF authors to explore what sort of cultures could successfully carry out terraforming projects of realistic duration.

Buy the Book

Worlds Seen in Passing: Ten Years of Tor.com Short Fiction

1: At the end of which you would have a mostly-O2 atmosphere on top of bone-dry carbon dunes. It would be wise to discourage smoking among any colonists.

2: Just look at how long it took the combined might of Earth’s industrial nations to crank up the CO2 levels in Earth’s atmosphere from 280 ppm to 400 ppm. I am as enthusiastic as the next person about seeing if we can pull off a remake of the Carnian Pluvial Event, but I fear I may not live to see this glorious experiment’s conclusion.

3: Better known for A Canticle for Leibowitz, which also features a global effort to radically alter a world’s habitability.

4: Mars seems to be revealed as more hostile every time we look at it. A recent paper suggests terraforming the place with local resources just cannot be done. Cue gnashing of teeth from Elon Musk.

5: Spinning Venus from its current hilari-stupid rotation rate to one with a night less than months long requires enough energy to melt the crust of the planet. Which would be counter-productive.

6: Fogg does suggest that Mars (as it was thought to be in the 1990s) could be transformed from a world that would kill a naked human in a few minutes to one that would kill a naked human in a few minutes in a very slightly different way. That amount of terraforming progress would take a mere 200 years. But his guesstimate was based on an outdated model of Mars; see footnote 4.

In the words of Wikipedia editor TexasAndroid, prolific book reviewer and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll is of “questionable notability.” His work has appeared in Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews and Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis). He is surprisingly flammable.

Well, there is the effort dedicated to the consumption of said invention.

Isaac Asimov in The Martian Way (1952) described fetching a chunk of water-ice from Saturn’s rings and bringing it to Mars. With present-day knowledge he would probably have added comets to his shopping list. That should provide enough material for a Martian atmosphere.

John Barnes’ “The Sky So Big And Black” depicts a several-generations-long terraforming of Mars as a crash program.

It has been suggested that learning how to terraform other planets could pay off later. Since by the time we learn how to do it, we may need to terraform the Earth.

And no sooner do you succeed in terraforming a planet than somebody goes and drops a beanstalk on it.

@1 –

I don’t think that effort could be described as “organized” though.

Also, how do you write that many words about terraforming in SF without even mentioning Dune?

If we do ever create the ability to leave our solar system in a reasonable time frame, it would seem to me that we would be better off putting our efforts into finding habitable or near habitable planets elsewhere rather then trying to change a Mars or Venus.

Besides from a purely environmental moral standpoint should we do terraforming on a planet wide scale. I mean think about it, here in California it can take years of environmental impact studies just to get permission to build a new stadium. Should we even consider drastically changing the natural environment of any planet?

@6 Sure, why not? If no one’s living there, then what’s the harm?

At the end of which you would have a mostly-O2 atmosphere on top of bone-dry carbon dunes. It would be wise to discourage smoking among any colonists.

Given that the article is called “The Big Rain”, I am not sure where you got the “bone-dry” bit from. Or the “carbon dunes” bit, which makes it sound like you expect all the carbon to exist in the form of charcoal rather than organic debris (dead algae).

Yes, a surface covered in flammable organic debris plus an oxygen-rich atmosphere does sound dangerously explosive. One wonders how we survive.

@7 Think of the efforts Star Fleet went through in order to insure there was NO life on a rock moon so Genesis could be tested. Even today we spend a lot of time, effort and money ensuring there are no biologicals on any of our Mars landers. I always thought why bother for a lifeless planet? Well because we are not sure it is lifeless and we don’t want to ‘contaminate’ Mars if there is, and how can we ever be sure there is NO life already there?

Personally I would have no problem if we could terraform Mars or Venus but there are plenty of people who would. Just because you can do a thing does not mean you should do that thing and I am just asking what we should ask before we even go down that road.

You skipped the Mars trilogy (Red, Green, and Blue).

Will Jenkins was Murray Leinsters real name, not a pen name for Williamson.

1: At the end of which you would have a mostly-O2 atmosphere on top of bone-dry carbon dunes. It would be wise to discourage smoking among any colonists.

Okay, so no H. Beam Piper characters need apply.

Heinlein’s ‘Farmer in the Sky’ hand waves the atmosphere issue but goes into great detail about the soil conditioning process.

Babylon 5 has a terraformed Mars where you have to wear a heavy parka and an oxygen mask to walk around in the open air and the weather can kill you. So, technically like parts of Terra.

True, but the story was actually bylined “Will Stewart,” which was used by Williamson.

@5 I agree Dune would be a good candidate for this. However it does kind of amuse me that Arrakis as described in the book is still way way more habitable than any planet besides earth we’ve ever discovered. You can go out naked in the desert and survive for more than a minute! Compare that to Mars where you will immediately begin to asphyxiate or Venus or Mercury where you will be baked in a second.

So basically we should get a really long hose and stretch it between Venus and Mars and pump some of Venus’ CO2 into Mars’ atmosphere. Kill two birds with one stone. A siphon wouldn’t work, so a pump would be needed, but if we’re making a119,740,000km+ hose, we could pop for a pump too.

Also, seeing all that sulfuric acid work on Mars’ iron laden soil would be really interesting.

@15: Thanks–the post has been updated!

The problems facing terra forming are indeed formidable when looking at Mars and Venus. Mars would require moving volatiles from the outer system and Venus would require, as was pointed out in the above essay, biocracking CO2 to oxygen and then sequestering the carbon.

However, Venus is already “habitable” in the sense that there is a level of the upper atmosphere that is near 1 Barr pressure and near Earth average temperature such that a floating habitat would be very viable. Oxygen and nitrogen would serve as lifting gasses in the much denser CO2 atmosphere. Maintaining a biosphere in floating habitats on Venus are not only doable, but practical for various purposes.

OK, shameless plug: In my recently self-published SciFi novel, there is a large habitat in that exact situation. It’s purpose is to provide a near 1G environment down a gravity well to isolate extensive genetic engineering labs where they may be very safe from accidental release of organisms into Earth’s ecosystem.

One of the tasks of the labs is to engineer the organisms that will be used by seed ships to be sent to the stars… to bioterraform carefully selected worlds that may be more easily terraformed than either Venus or Mars. The key is to find worlds that look halfway between Mars and Venus… an atmosphere with lots of N2 and H20… and too much CO2. Those worlds would be cloud seeded with “floaters”… engineered symbiotic colonies that look much like kelp with gas bladders filled with oxygen. As the atmosphere is converted, the “leaves” drop to sequester the carbon as biochar then as leaf litter. The litter would contain extremophiles that would slowly convert rock into soil. The floaters eventually end up on the surface, but continue to float on the oceans as the “global cooling” allows the water to rain down and wash the “leaves” into the ocean sediments… This all takes millenia to happen.

When the worlds are ready for more complex ecosystem development, the synthetic minds on the seed ship engineer appropriate lifeforms… eventually introducing Earth standard organisms including humans.

My first novel “All The Stars Are Suns” the first of a series dealing with the ugly politics and personal issues of launching these seed ships. I’m currently writing the next in the series “Raven’s Roost” about the lives of the first culture to develop on the first terraformed world to explore what it would be like to live on such a world with a bioengineered ecosystem and advanced biotechnology… but stone-age / early metal working (no smelting available) technology in every other way. The story also deals with issues nearly every other SciFi story fails to discuss… how DIFFERENT a world with a different gravity and atmospheric composition would be and still allow humans to thrive.

And then you have the terraforming in Joan Slonczewski’s Fold novels (The Door into Ocean and sequels). In this universe it’s possible to traverse the distance between solar systems through something called the Fold, but all the habitable planets that were found so far already had some type of local fauna or other. So “Terraforming” means boiling the planet’s surface from orbit until all of the local biologicals are dead (well, atomized), waiting for the planet to cool off, and reestablishing a terran biosphere.

Niven and Cooper’s _Building Harlequin’s Moon_. IIRC it involved 60,000 years of coldsleep so that those who started the process can see the end. Granted that book is a bit more ambitious than most about what the terra-forming involves…

There is a problem when trying to accurately project the time scales of these efforts from our current point of view. The advancements of our species and the growth in the mass and energy under our influence is increasing exponentially. Not to mention engineering projects that amount to extreme multipliers of this effort. Have you ever heard of orbital rings? You know, the newer idea for a megastructure that would put space elevators to shame and would make it affordable to commute to low earth orbit? I recommend finding Isaac Arthur’s youtube video of that name, because its potential to cheapen and accelerate work is ludicrous You can imagine it being used as a launch railway for spaceships, reducing the need for fuel by many kilometers of delta v. Or, it can be used to launch gases across the solar system such as from Venus to Mars, or hydrogen from Jupiter or even then sun such that we have the ingredients for water. The cost to get the first ring started? A few tens of billions. Kinda affordable when you think about it. The cost to build another or many more? Vastly less since the first could be used to lift material into space. The point being that making these time and cost judgements from our perspective is hard because our perspective is wrong especially if we keep getting our ideas from old Sci fi.

@17: Hose? That’s so last century. What you need is a wormhole. Though I’m not sure the pressure gradient has been thoroughly worked out.

Posting on behalf of James (the original poster) to say that he’s currently offline and unable to join in the discussion until later tonight, but will respond to questions and other comments as soon as possible!

@5, or Kim Stanley Robinson’s Mars series, which is basically entirely about terraforming Mars, as well as 2312 which contains some very interesting theories about & techniques for terraforming various celestial bodies in the solar system.

@17,

If we don’t have a pump, maybe we could put someone at the Mars end to start the suction.

@13 The biggest flaw in Farmer in the Sky was the assumption that, once you got the temperature up to Earth normal, Ganymede had pretty much the same composition as Earth, and once the soil was conditioned, you would be good to go. Actually, the moon is thought to have proportionately a lot more water than Earth, enough so that if it melted, there might not be much, if any, dry land to farm.

My biggest concern about terraforming is un-terraforming, which is what we seem intent on doing to Earth.

2: I’ve always wondered why Asimov went for the rings and not a more distant moon of Saturn. Escape velocity from the rings is root two times 17 to 75 km/s. There are much easier places to get water, which is not especially rare in the Solar system, than the rings.

There are at least two issues with cometary ice. One is that it’s far away: orbits from the Kuiper to Mars take decades, which I admit should not be an issue for someone planning in centuries or millennia. The other is that comets show up at cometary speeds, which raises the possibility impact might blow off more material than it delivers. I can think of at least one trick to manage this (send payloads in gravitationally bound pairs, with flybys such that one ends up slowed wrt Mars and the other zooms off; basically what may have happened with Triton) and there are probably others.

8: from the fact Venus has, iirc, about 20 ppm water in its atmosphere, about the same fraction as Neon in Earth’s atmosphere. Granted, that’s 20 ppm of a much dense atmosphere but if I’ve done the numbers correctly, that’s a hundred thousandth the amount of water as Earth has.

Apparently there was a panel on the economics of terraforming at Worldcon. Did anyone attend? Is there a business case? Not that everything worthwhile needs a business case but it would be pleasing if there was one.

A lot of SF tropes are kneecapped in the real world by our short livespans and how fragile we are. We really need to be more like immortal tardigrades. Someone get to work on that.

It may not be long before we get a crack at “terraforming” Antarctica and/or Greenland.

Starting small is probably a good idea.

The upside of terraforming being slow is that unraveling terraforming may also be slow. For example of the downside of easy, fast terraforming, see the backstory to Paul Preuss’ Re-Entry, where a lot people died when ecosystems collapsed.

Try The Forgotten Planet, by Murray Leinster. It was published in 1954, but based on stories from 1926 and 1927. Most of it is a men-vs-monsters story, but the prologue describes what is clearly terraforming, though the word is not used. It takes centuries, even starting with the improbable advantage of breathable atmosphere and fresh water, but no life at all. During a move, a card file (!) Is upset, and the planet’s only record is lost. This sets up the monster bit (giant arthropods and fungi), but also makes the valid point that interrupting terraforming would likely not be a good idea. The word “ecological” is used.

In Against Infinity Gregory Benford had colonists terraforming Ganymede with biological machines. Naturally the animals mutate, and mutated animals are counterproductive to the terraforming effort, so the colonists have to go out and hunt the mutants. Benford has said, I think, that this book’s starting point was a desire to revisit Farmer in the Sky and do it better.

29. Asimov probably thought that moving a cubic mile block of ice from the rings would be easier than moving one of the known moons of the outer planets (or breaking off a sufficiently large chunk from one of them).

@30: You’re probably thinking about Jesper Stage, a Swedish professor in economics. He has held several lectures where he takes various economic theories and cross them with various science fictional concepts. I was at his lecture last Swecon on Economics of Terraforming, and it was basically an introductory lecture on long-term investments as applied to terraforming, and the surprising conclusion was that sf authors in this case are better at economics than they are at physics or biology.

You might find his article Not long before the end? SF and the economics of resource scarcity in Fafnir interesting.

@19: Considering that the 1 bar region of Venus’s atmosphere is right in the middle of Venus’s sulfuric acid cloud layer, building a floating platform that would not corrode away would be an *interesting* engineering challenge.

Warm up almost any moon outside of the asteroid belt, Io being a significant exception, and you get a deep ocean world for as long as it takes all the volatiles to vanish thanks to the low escape velocities. It might be tricky setting up an Earthlike ecosystem on a Warm Europa, for example, because there would be hundreds of kilometers of water (and maybe a layer of weird ice) between sunlike and where the nutrients would be.

Still, useful skills to develop given that deep ocean exoplanets seem to exist.

@34: There’s an interesting take on this in Stirling’s planetary romance books (The Sky People and In the Courts of the Crimson Kings). They’re set in an ATL in which Terran astronomers confirm early suspicions that Venus is a super-lush jungle-and-ocean planet, while Mars is a desert laced with canals. Later explorers discover that both were terraformed, as in literally made living using organisms from Earth. But the laws of physics still apply; Mars, unable to hold onto its engineered atmosphere, is slowly dying, its people genetically engineering themselves and local animals and plants in order to eke out more generations of existence while aware that eventually their best efforts must fail.

And then there’s a lot of plot that I won’t spoil because the books are quite good.

all the volatiles to vanish thanks to the low escape velocities

This is a century-old shibboleth based on geological timescales and James Jeans. Then most science fiction writers forgot that it was applicable to geological timescales, and imagined it happening over a few millennia.

(it’s bitten us recently scientifically, as astronomers have been shocked to find hydrogen planets closer to their sun than Mercury is to ours. Turns out they don’t evaporate to nothing just like that, if you go back to the calculations. The impossibility of a hydrogen planet close to a star was based on the traditional cultural trope of cotton-candy volatiles, rather than anyone doing the numbers)

Richard R Vondrak showed in the 70s that a volatile atmosphere on a low-escape-velocity body could persist for millions of years. We don’t see that in the solar system because it’s been much more than millions of years.

Also, you need to include Jupiter’s own escape velocity, which is a factor (I think it’s the root-sum-square of the moon and the planet) and that’s not a small escape velocity.

Aside from Hal Clement’s Noise, are there any novels about deliberate ecopoiesis on a deep ocean world?

@43

Alison Sinclair’s Blueheart is about terraforming a waterworld. Maybe not quite what you were asking, though.

The unappreciated point about terraforming is that the energetics for making an atmosphere out of regolith is similar to the energy to propel fast starships. If you can do one, then you can do the other. A 50 petawatt beam to push a 1,000 ton sail to 0.5 c can also pyrolyse oxygen out of regolith and make an atmosphere in a couple of decades. Moving a 100 billion ton payload of N2 from Triton to Mars needs a delta-vee of 15 km/s and the same energy as pushing a 1,000 ton Starship to 0.5 c.

In Seveneves By Neal Stephenson, the Earth is (re)terraformed back to a survivable level, although that was mostly a question of waiting for it to cool back down after being bombarded by the moon and adding back some water.

Full terraforming takes a long time and a lot of effort. But partial terraforming, providing a thicker and warmer atmosphere (what I call proteroforming, after the proterozoix period) that makes paraterraforming large volumes a lot more practical, and enables unpressurised greenhouses to be used for life support, should be a lot easier, whilst still providing most of the benefits. Imagine Mars with a ~100mb CO2 atmosphere and surface water at certain times of the year. Homesteading would be a lot more practical – particularly if the atmosphere contains a few mb of free oxygen that can be efficiently extracted. People wouldn’t need pressure suits to work outside, and certain hardy (engineered?) plants could grow without needing greenhouses. A Mars of genetically engineered taiga forest and tundra?

26: To channel Martin Prince, I am aware of KSR’s work. He’s a good example of someone who compresses the time needed to transform Mars for narrative convenience. But I guess if someone is looking for warmed-over Co-Evolution Quarterly material, KSR is a good bet.

I always enjoy giving people unlabeled quotations and getting to guess which are by KSR and which by Jerry Pournelle.

Fascinating read

@43: stop doing that :-) There’s the planet where all Earth’s cetaceans went – probably without assistance from Douglas Adams – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cachalot_(novel)

“irritating alien creatures found on the planet”, but that may be a spoiler ;-)

It’s a good while since I read it, but I don’t suppose they have fish flown in… surely?

I was sure this article was going to mention KSR’s Mars Trilogy. I’m on the third book and while it’s a great read, even non-science-savvy me is pretty sure this is about 1,000 faster than terraforming would actually successfully occur. Although I would definitely trust us to be better at warming up a planet than cooling one down.

There’s the original Total Recall where Arnie pushes a button and Mars gets an atmosphere in moments. Alien tech at its finest..

The insta-terraform scene in Total Recall is evidence Arnie’s character is still in that chair in the We Can Dream It For You office.

Mos def! And so is that final fade out to white! (Also a rare case where the modern remake is a bit better — at least more watchable —than the original film.)

When I was a kid, I worked up a rough calculation of what an even division of the planet and its resources would look like — my math and research was bad enough I won’t mention any numbers, but it raises the question — how do we tell folks that they aren’t allowed to have ~1/8,000,000,000,000th of the world’s resources?

Consider the hard limits — there’s one day’s worth of sunlight over half the planet each day — the other half of the planet when shadowed can only radiate off so much heat into space — are there any circumstances which should allow a person to use more than their share of either number? (either using more energy than the sun applies to a human sized share of the earth’s surface, or generating more heat than the earth can radiate off).

https://dothemath.ucsd.edu/2012/04/economist-meets-physicist/

4 centuries ~ 10^4 increase in energy use? That’s _twice_ what I thought the limit was before envenusification is an issue. Whoot!

At a conservative 5000x present day energy consumption, it’s interesting to see how quickly we use up non-renewable energy resources. Even treating granite as U and Th ore….

If fusion happens at all, it will use D + T and we make T from Li + n. Li too is a non-renewable resource.

Anyway, it’s an argument in favour of using incident solar because at least that way the raw heat won’t kill us all (since the sunlight was going to hit the Earth anyway). Or if you do have to use fission or fusion or SPS or total conversion, remember to use an asteroid to transfer momentum from Jupiter to Earth so our orbit moves farther from the sun enough to reduce incident light by the amount we’re adding heat.

Nice article! I wish it had been longer and included some mention of KSR’s Red, Green, Blue Mars trilogy and also the terraforming effort by the Dusters in The Expanse.

If they are part of the one percent. Simply use one’s social and economic power to force the 99% to use as little power beyond what is needed to make biochemistry function. It is a simple and just solution, bearing in mind it’s the one percent who get to define the legal definition of just.

Radiating heat, btw, is the sole Killer App (aside from information) that I can think of for space industrialization. Pretty much any other resource available in space is available cheaper on Earth but there’s a hard cap on how much heat the Earth can radiate.

Of course, another route is the population decline talked about elsewhere. It seems within the current behavior of humans that rational economic and personal decisions carried out over generations will result in low tfrs and negative growth rates. Populations do have inertia but minus pop growth can shrink populations surprisingly quickly (and of course the occasional nuclear exchange with not only provide abrupt decriments, they will almost certainly contribute to people’s disinclination to have kids.).

Red, Blue, Green Mars uses a ludicrously short timescale but at least it distracts from the ethnic stereotyping and KSR’s dubious grasp of orbital dynamics.

The Expanse has as a plot point one of the big challenges in terraforming, that the time needed means economic realities may evolve such that the project no longer makes sense. When they began terraforming Mars in the Expanse, Earth was the only garden world humans had, plus of course there were a lot fewer space horrors planning to eat our brains.

can shrink populations surprisingly quickly

Citation needed

Read most of the Mars Trilogy by KSR, but half way through Blue (the last) it was revealed that “living dirt,” or actual soil, could not be produced in a laboratory due to its complexity.

Killed the whole series dead. Mind you, that’s 1700 pages into a 2000 page epic.

You would think someone would have tested that before even beginning the trip to Mars.

Wasted a fair amount of life on something that sounded good, but was wholly implausible.

Well, take Japan: 127,974,958 people in 2015, 127,185,332 in 2018, if online sources can be trusted. Down 789,600ish people just because the number of people dying is bit higher than the number being born.

Roger Zelazny’s “The Keys To December” is a description of possible unintended consequences of terraforming a planet that starts out habitable, just not habitable by the terraformers. Even in this scenario it takes centuries; Zelazny makes the case for deciding to take millennia instead.

45. A petawatt laser is by definition a WMD. This is a case of the Law Of High Energy Launch Systems: they can be used as weapons or can become planetary industrial accidents. This makes the politics of building launch systems much more complicated than it would seem at first blush.

58. The other use for space industrialization is to move the generation of toxic byproducts away from a so-far undestroyed biosphere (though we are trying hard).

Re the acid on Venus – maybe someone could figure out a way to spray the atmosphere with an akaline liquid!

I’ve been putting off reading the KSR Mars series for years, but was looking forward to it someday. After the previous comments I’m wondering if I should give it a skip. Looks like it might be a bit disappointing for me.

Ah, well. Plenty of other books at the library

@65

The process of terraforming is bound to be complex, and aside from the highly-accelerated time frame, I think that KSR’s exploration of it is interesting. Certainly the intermediate ecologies that he proposes are worth a look, and if you’re interested in how a biosphere works, he considers this at some length.

I haven’t looked at Blue Mars in a long time, but I find nothing erroneous about “living soil” being impossible to synthesize in the lab. Soil’s an ecosystem – getting the mixture of clay, organic material and minerals right is one thing, but getting the balance of nematodes, collembolans, fungi and bacteria right is going to be tricky. And these organisms can’t be synthesized in the lab, certainly not now and not likely at any envisionable point in the future.

@66: Thanks. That’s kinda why I mentioned it… see if anyone thought they were still worth reading. Maybe I’ll just move them down what has always been a huge TOREAD list

@28,

It is, of course, much easier to break something than build it. The current un-terraforming project is, in geological terms, about as fast as a car crash, but, more importantly, provides instant rewards to some.

@43 Novels about deliberate ecopoiesis on a deep ocean world: how about Greg Egan’s “Oceanic” (novella)? The ecopoiesis already happened so long ago that no one understands it anymore, but people in the story are studying and trying to figure it out.

I may have missed that particular Egan. Well, it’s not like my Mount Tsundoko is threatening to topple and crush me.

wyrdsmythe @65:

I think the first two books of the Mars trilogy are brilliant; the third is more problematic, but has much that is good and interesting in it. (And, in my opinion, it’s possible to read the first two as forming a complete story, without really needing to read the third.)

(Also, I’m an astronomer, and I don’t get a sense of KSR being particularly bad at science. For what it’s worth, I find him to be one of the very few writers I’ve read who understands how science works as a social and intellectual process.)

@71: Thanks, that makes me feel much better about reading them. As my science skills are likely sharper than my literary skills (without claiming great acumen in either), I tend to be more sensitive towards bad science than bad writing.

@70: As a lover of diamond-hard SF, and as someone with a fascination for theories of consciousness, Egan is one of my very favorites.