When you play the game of thrones, you win or you die…

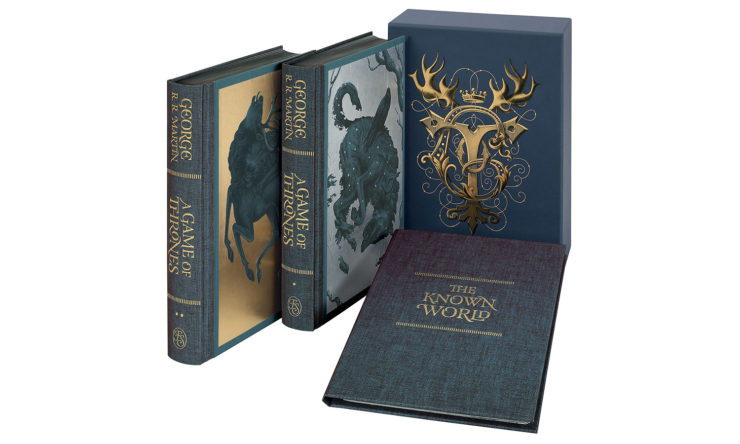

A publishing phenomenon; the biggest TV series in the world; a book that revolutionised a genre. A Game of Thrones is also, above and beyond all these things, a uniquely addictive piece of literature, claiming legions of fans and winning vast critical acclaim, and now The Folio Society presents the ultimate illustrated collector’s edition, with art by Jonathan Burton and a special introduction by fantasy author Joe Abercrombie.

The Seven Kingdoms are hedged in by enemies, riven by feuds, and sliding towards civil war. King Robert Baratheon’s closest adviser dies under mysterious circumstances and his old brother-in-arms Eddard Stark is offered little choice but to take the job. Powerful families strive for dominance, shadowy power-brokers jockey for advantage, dark powers rise beyond the borders, and Stark and his family find themselves thrust into a world of intrigue and treachery where honour is unlikely to carry the day. The results are shocking, bloody, and very, very dark . . .

In 1996, when George R. R. Martin’s A Game of Thrones was first published, darkness alone was nothing new in fantasy. In the 1930s Robert E. Howard’s Conan the Barbarian was dark and muscular with a dash of kinky. In the 1950s Poul Anderson’s The Broken Sword was dark and tragic with a streak of Viking fatalism. In the 1970s Michael Moorcock’s Elric of Melniboné was dark and brooding with a side order of doomed decay.

But those were generally shorter, more focused stories. By the 1980s and 1990s the commercial juggernaut dominating the speculative shelves was epic fantasy—big series of big books about swords and wizards and dragons in detailed, medieval-style invented worlds, and the bigger and more detailed the better. Those kinds of books were still very much in the shadow of J. R. R. Tolkien’s definitive fantasy colossus, The Lord of the Rings.

So it was that when I was growing up fantasy seemed to consist of series striving heroically to out-Tolkien Tolkien in the grandeur of their setting, the clarity of their morality, and the familiarity of their plot and characters. You could say the genre had become just a tad predictable. You knew who the good guys were, you knew who the bad guys were, and the reader was left with little doubt about who was going to beat who. Which is one reason why I started to drift away from the genre and, by the early 1990s, more or less stopped reading it.

When a few years later a friend handed me the considerable weight of A Game of Thrones saying, ‘You used to be into fantasy, you should give this a try’, I looked at the font on the cover—with the shiny knight and the big castle—and I smiled indulgently. Please, I thought, I know how THIS goes. What Martin gave me, of course, was the best kind of slap in the face.

Originality is a wonderful thing. But it’s like salt. Too much can ruin a meal. What’s brilliant about A Game of Thrones is the way it mixes the well- loved with the radical, the way it feels just familiar enough to make you think you know what’s coming. It’s the execution, and the combination of elements, that adds up to something new. Something truly shocking, even. ‘You’re safe,’ it seems to say, ‘you’re among old friends.’ Like many of its most dangerous characters, it comes with a smile. Then it sticks the knife in.

Martin conjures up a huge, rich world with lashings of history and detail. He drops in an ancient evil returning and bloodthirsty savages beyond the edge of civilisation. He delivers an epic sweep of love and war featuring kings and queens, lords and ladies, a little dark magic, a whole lot of swords, and, of course, a handful of dragons.

So far, so (relatively) familiar, but the actual style of writing was one I’d never seen applied to fantasy before. Martin writes in limited third person, as it’s sometimes called, where each chapter remains rooted in the specific point of view of a single character. There’s a large rotating cast, but at any one time everything is seen through the eyes of one person, delivered in their voice, coloured by their prejudices, suffused by their attitudes, memories, hopes, and failings.

I was used to a more stately storytelling style, an omniscient narrator who floats above the action, occasionally dipping into thoughts and feelings but generally keeping aloof—narration by dignified wizard. Combined with the focus on setting that epic fantasy tended to aim for, that produced stories which felt like they were told all in wide-shot: vast and magnificent sweeps of countryside lovingly rendered, but with tiny little cardboard cut-out characters lost in the distance. A Game of Thrones squashes us right up against a vivid and diverse cast; it puts us right in their heads, lays bare their dreams, reveals their secrets. It’s epic fantasy, sure, but one told in intimate, visceral, uncomfortably tight close-up. Each chapter is even titled with the name of the character we’ll be with. This, it seems to say, right from the start, is about PEOPLE.

And what a cast. They’re a mess of contradictions sometimes half embracing fantasy clichés, sometimes stomping all over them, sometimes both at once. They’re not just heroes or villains (though there are plenty of heroics in the book and no shortage whatever of villainy), they’re all capable of being both, depending on the circumstances and the viewpoint from which they’re seen.

Eddard Stark, the closest thing to a central character in A Game of Thrones, is fundamentally a good man struggling to do the right thing, but the strict sense of honour that might be a cardinal virtue in another book becomes a fatal flaw. Queen Cersei, by contrast, seems vile, but is driven to cruelty by an abusive husband, a domineering father, and a desperate need to keep her children safe. Her brother Tyrion is perhaps Martin’s definitive character—a scheming dwarf held in contempt even by his own family, a man as far from the knightly ideal as could be, but through his own eyes we see him to be thoughtful, witty, loyal, capable of warmth and self- sacrifice.

In The Lord of the Rings, and the many fantasy epics that followed where it led, there is an objectively right and a wrong side. Sauron is evil, and to resist him is good. Characters can only be morally ‘grey’ in the degree to which they fail to resist Sauron, or are tempted into alliance with him. So Aragorn has his worries and his weaknesses, his concerns over whether he’s the right man for the job, but he never really has to question the cause. It’s never in the reader’s mind that Gandalf might be wrong. The nature of the world doesn’t allow for it.

In A Song of Ice and Fire—the series of which A Game of Thrones is the first part—there are few such certainties. The world is murky, full of doubts and unknowns, packed with ambiguous characters, necessary evils, lose–lose choices, and mixed motives. It is a world beset by supernatural perils, to be sure, but also one in which the greatest evils are man-made. There is no ultimate truth, no unqualified right side. To quote Martin himself, ‘In real life, the hardest aspect of the battle between good and evil is determining which is which.’

And the dirt in Martin’s Seven Kingdoms is not just of the moral kind. At first it seems a place of shiny pageantry, buffed-up heraldry, tourneys and banquets galore, but it isn’t long until the glitzy veneer starts to peel away, revealing something as rotten, violent, and corrupt as anything in literature. There is sex and there is violence, lots of it, all treated in the same unflinching, unromantic, unapologetically adult way. There is a brutal honesty about everything; a sense of realism, or at least of being shown an unpleasant aspect of reality that wasn’t often present in fantasy before.

It’s a world that doesn’t care whether you’re one of the good guys or the bad, whether you’re an extra or part of the key cast. A world that is in-different to your pain. A world closer to our earth than Middle-earth.

And the thing about Martin, he doesn’t just pay lip-service to the idea of a gritty narrative. He doesn’t just take the same old heroic storylines, sprinkle them with sewerage, add a wound and a plague sore or two, and proceed to the happy ending. Martin follows through. The book is packed with the brutal randomness of real life, with shocking betrayals and devastating consequences. The narrative refuses to run on the usual rails in very much the direction we expect. Rather we are soon clinging on white-knuckle tight as it veers and bounces like an out-of-control mine cart, and central characters are horribly disgraced, irreparably maimed, and frequently killed.

The death of a certain key character (I’ll do my best to avoid spoilers) remains shocking to this day, but it’s hard to convey how truly ruthless and radical it seemed at the time. I can remember reading it, convinced that it couldn’t happen, sure there’d be some last-minute reprieve, then the disbelieving smile spreading across my face as I realised that fantasy had become dangerous again. As someone who’d read and loved the genre their whole lives, it was a light-bulb moment. It demonstrated that you could do something shocking and character-focused while still writing epic fantasy.

Twenty-three years after the book was first published, the TV adaptation, Game of Thrones, has become, of course, a cultural phenomenon. It’s been amazing, as a fan of the books, to see something that always seemed so resolutely rebellious and personal achieve such wild success. When the person in the street thought of epic fantasy ten years ago, they thought of Lord of the Rings. Now they think of Game of Thrones too. It’s expanded people’s notions about what fantasy on screen can be. Not only epic, magical, heroic, but adult, shocking, and dangerous too. But this book, and its sequels, had already changed what fantasy could be for a new generation of writers, and ushered in a new era of character-focused realism, moral murk, and unrepentant grit.

–Joe Abercrombie

Artist Jonathan Burton on illustrating the Folio edition of George R. R. Martin’s A Game of Thrones: