The Eclipse series of anthologies edited by Hugo-nominee Jonathan Strahan are, as the flap copy says, “in the spirit of classic science fiction anthologies such as Universe, Orbit, and Starlight.” I look forward to them each year, because without fail, there will be several stories within their pages that take my breath away.

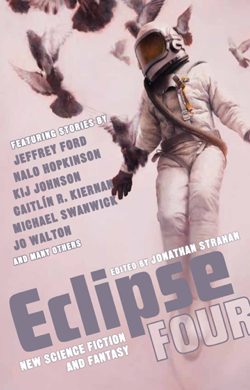

Eclipse Four has just been released (today, in fact) through Night Shade Books. Its table of contents contains writers such as Caitlin Kiernan, Emma Bull, Nalo Hopkinson, Jo Walton, and Kij Johnson—and that’s not even mentioning the rest of the stellar list of contributors. The stories range from mind-bending, strange science fiction to fantasy and everything in between. (It also has one of the prettiest covers I’ve seen in a long time, but that’s neither here nor there.)

Some spoilers below.

Strahan’s deft hand as an editor is at work in the arrangement and selection of stories for Eclipse Four. I found it to be a deeply enjoyable, challenging and varied anthology that explores everything from what a story is made of to what the afterlife could be to outer space.

The anthology is organized well. The stories flow into one another without any jarring juxtapositions, yet are also so widely varied that—despite the occasional theme that seems to crop up—they never feel like re-treads. The pieces are all original to this volume, which makes the variety and smooth transitions between stories even more impressive; it’s not like these pieces were selected reprints, which would likely have made them easier to work with. I applaud Strahan’s editorial choices.

As a whole, the stories themselves are excellent—most are complex and challenging in the best way, with gorgeous writing and gripping narratives. It’s the sort of anthology that it’s good to read with pauses between the stories to properly appreciate the depth and variety on display.

Story-by-story reviews:

“Slow as a Bullet” by Andy Duncan: Duncan’s offering is odd start, mostly because of the narrative voice. The told-tale story construction can be great, but it’s a hard trick to pull off, especially when playing with dialect. While I fell into the voice after a few pages, it began and remained slightly overdone—dialect at its best is unobtrusive yet convincing; Duncan doesn’t quite manage that. However, setting that complaint aside, the story itself is a strange, fun exploration of what magic can be made of. The arguments over what color is the slowest, for example, are intensely entertaining. The narrator’s view of the events color his telling of the tale, of course, but that’s what makes it interesting—reading between the lines.

“Tidal Forces” by Caitlin R. Kiernan: My immediate response to this story was a breathless oh, because there wasn’t much else I could find to say about it. This is a story that well and truly demands a second reading, and for the best possible reasons. Kiernan’s slow, tense, emotional buildup to the climax of the tale is perfect; the non-linear construction, the exploration of stories and linearity within the text, the shuffling of cards as a shuffling of days and memories, and the way the narrator dances around the inevitable all create a fascinating story that shifts and slips from the narrator’s hold as she tries to tell it. The strangeness, too, is welcome and lovely—a shadow of a shadow, and a black hole in a woman’s side. The images in the text are so well-wrought that they have a tendency to stick in the mind after the story is finished; the shifting of flesh around the edge of the hole, for example, or the way Kiernan describes sunlight, or the light of a muted television. The interplay between the narrator and her lover is also spot-on, full of emotion and the occasional bitterness that long-time partnership brings. “Tidal Forces” is a great story.

“The Beancounter’s Cat” by Damien Broderick: Broderick’s tale is one of the mind-bending SF stories previously mentioned. There are talking cats, a world where technology has become magic, AIs, space-construction, and all sorts of other things. The delicate touch Broderick uses for his world-building is at times wonderful and at times frustrating; there are several questions posed and very few answered by the end of the story, but in some ways, that’s what makes it interesting. Broderick’s story didn’t quite connect with me as thoroughly as I would have liked, but it was well-written and entertaining.

“Story Kit” by Kij Johnson: Johnson’s story is another stunner. It’s a cobbled-together metafictional piece about loss and coping (or, as it were, not coping), built out of asides, bracket-notes, “rewrites,” and chunks of story within chunks of a second story, all culminating in a sharp-edged, short final paragraph. The craft on display in “Story Kit,” which begins with Damon Knight’s six types of short fiction, is part of what makes it so impressive—but it was also the rich and visceral agony of loss that the narrator tries so hard to recapture, to dance around, and to put on paper without facing it head-on. The story is complex and layered, not a typical “this is how it goes” sort of piece, and the play with what a story can be is very well-wrought. This is another story that prompted me to put the book down and savor it for a moment after finishing. I applaud Johnson’s creativity with form and craft.

“The Man in Grey” by Michael Swanwick: Swanwick’s offering is a short tale about reality and what it isn’t through the eyes of the titular man in grey, who’s a sort of behind-the-scenes guy for the “great game” that is “real” peoples’ lives. It was an engaging read but not one of my favorites; though the construction of reality in the story is briefly interesting, the shine wears off before the story ends. It isn’t a flexible concept. “The Man in Grey” is a functional story, but juxtaposed with the other tales in the volume, it’s not terribly impressive.

“Old Habits” by Nalo Hopkinson: Ghosts and regrets are the central focus of Hopkinson’s contribution, an emotional story about an afterlife shopping mall. The mechanics of the afterlife for the ghosts trapped in the mall are heartbreaking and fascinating in equal measures—the “on the clock” moments where they relive their deaths, for example, and the blackness outside the glass doors, and the possibility of devouring the remaining life of another ghost. The final moments of the narrator’s life as he relives it, with his husband and son watching as he dies on the escalator, are absolutely wrenching, thanks greatly to Hopkinson’s liquid, effortless prose, including tight stream-of-conscious narration. “Old Habits” is an understated, brilliant story.

“The Vicar of Mars” by Gwyneth Jones: “The Vicar of Mars” is another great story, exploring faith, fear, and the Mars of a distant future through the eyes of an elderly alien vicar. Humans are somewhat tangential to this story, except the woman whose psychic distress has created monsters that outlive her—a terror which is oppressive and hair-raising throughout the story for the reader as well as Boaaz, the vicar. The weights of hallucination and terror are woven into a story rich with personal details, like Boaaz’s love for mineral-hunting, his friendship with the immortal Aleutian alien Conrad (which has sharp edges), and his interactions with his faith. The ending paragraph is a real stunner, also. There’s so much going on in Gwyneth Jones’s story that it’s hard to single out what makes it so gripping, but it truly is—beautiful world-building, slippery terror, well-written aliens with believable motivations…Jones does everything right here. I deeply enjoyed “The Vicar of Mars.”

“Fields of Gold” by Rachel Swirsky: Swirsky’s story is another about ghosts and the afterlife, which seems to be an unintentional theme cropping up here—three stories in a row. Hers is different from those that have come before, though; the after-death world for her ghosts is a series of parties, paired with a loss of self and the ability to make connections. The interesting world-building aside, though, it’s not a wonderful story—slow, for one thing, and hard to feel engaged by, for another. It’s still enjoyable, but it’s not top-notch.

“Thought Experiment” by Eileen Gunn: “Thought Experiment” is my least favorite of the volume. It’s not engaging or exploratory in the way I’ve come to expect from the other work included here; instead, it’s a same-old same-old sort of time travel story with a predictable “twist” at the end. The narrative skims too much for the reader to connect.

“The Double of My Double is Not My Double” by Jeffrey Ford: A strange and surreal story about doubles and doubles of doubles, Ford’s piece is comical and hard to get a grasp on. The worldbuilding has some glitches where bits don’t add up quite the way they should. I didn’t particularly like it, but there’s nothing functionally wrong with it, either.

“Nine Oracles” by Emma Bull: Bull’s story is about nine women who have been Cassandras—and in some of the shorts, how horrible it can be to be right when it’s too late for anyone to listen anymore. It’s an interesting series of vignettes, but I’m not certain it works quite right as a story. The emotional effect is weak in some of the shorts; the story as a whole ends up bland.

“Dying Young” by Peter M. Ball: Ball’s story feels like a “Weird West” tale in style but is actually SF, with dragons made from gene mutations and cyborgs and the like. The combination works well, mixing magic, tech and the adventure-story sensibilities of a western. The lead character has to make hard decisions and deal with protecting his town; familiar and engaging themes. The ending, where the dragon gets to walk out of town and the narrator’s the one who did the killing, is particularly satisfying after we’re led to believe the town’s about to go to ruin.

“The Panda Coin” by Jo Walton: Walton’s story has a fascinating setup, and the world she builds, with its tensions and castes, is hard not to be drawn into. There are so many unanswered questions as the story follows the coin, bouncing from person to person, but that only adds to the enjoyment. “The Panda Coin” is another story built of lightly connected shorts, but it works as a whole, with its own tensions and resolutions.

“Tourists” by James Patrick Kelly: “Tourists” is a follow-up to Kelly’s Nebula-nominated story “Plus or Minus.” As a sequel it’s fun, but as a stand-alone story it wanders. For a reader curious about what happened to Mariska, watching her grow into her future and form a relationship with Elan is pleasurable, but I find it hard to imagine that someone unfamiliar with the previous stories in the cycle would have much interest—there’s no real movement of plot; it’s an exploration more than anything. On a personal level, it was enjoyable, but critically, it doesn’t stand up well on its own.

*

Eclipse Four was thoroughly enjoyable. It’s well worth purchasing, especially for the absolute brilliance of the best pieces: Kiernan’s “Tidal Forces,” Kij Johnson’s “Story Kit,” and Gwyneth Jones’s “The Vicar of Mars,” among others. The few stories which were disappointing in comparison to the rest were still well-written; nothing in the collection is actually bad. Strahan’s Eclipse books are one of the best original anthology series published today, and this volume is no exception. It’s high-quality—challenging, intense, emotional and riveting at turns, and sometimes all at once. I expect to see several of these tales on next year’s awards lists.

Lee Mandelo is a multi-fandom geek with a special love for comics and queer literature. She can be found on Twitter and Livejournal.