Before I looked for girls or boys, I was looking for doors first.

It made sense, being born under a Nebraska sky that went on for miles: farm boy land. A dust bowl town was not a place for a queer girl-child; the whicker of wind through corn stole your breath if you tried to breathe too deeply, feel too much. It wasn’t a town for being yourself. It was a town for being farm girls, waiting for their farm boys. Farm boys, farm girls, and nothing in-between. Certainly not farm girls who crushed too hard on their best friends, and were then crushed in return. There was no escaping the endless plain. Not in a cornfield that was a kingdom and stalks rattled like dried bones in the night.

There was only one way, one kind of book, where farm kids got the kind of story I needed.

The kind of story where the world opened and the endless sky let you breathe. Say what you will about the farm boy trope, but it gave hope. Dorothy Gale and Luke Skywalker were my lifelines, and I spent years looking for my doorway—not just off the farm, but out of the world that was wrong in ways I didn’t have words for. One that didn’t have words for me.

I wasn’t given the word for queer, but I was given many words for wrong.

Doorways were elusive, but I knew where to go for more words. Even a small farm town had a library—squeezed in and forgotten between the shadows of the courthouse and church steeple. It had a haphazard fantasy collection—McCaffery, Gaiman, Lackey, among others—and I read it dry. Acquire enough words, I thought, and I could find the ones that would overwrite the ones that didn’t fit right. Look in enough books, and surely I’d find the right doorway. I kept looking long past the cusp of adulthood.

The words that became real doorways would come later, in furtive glowing screens and the burgeoning and delightfully unrestrained nascent internet of the late 90s and early 2000s. I learned words for what I was, and made up stories with friends of what those stories could be—all of them with happy endings. Growing up queer, searching for doorways, and the way it kept me alive became just a muddle of a ‘fantasy nerd’ childhood, almost cliche at this point.

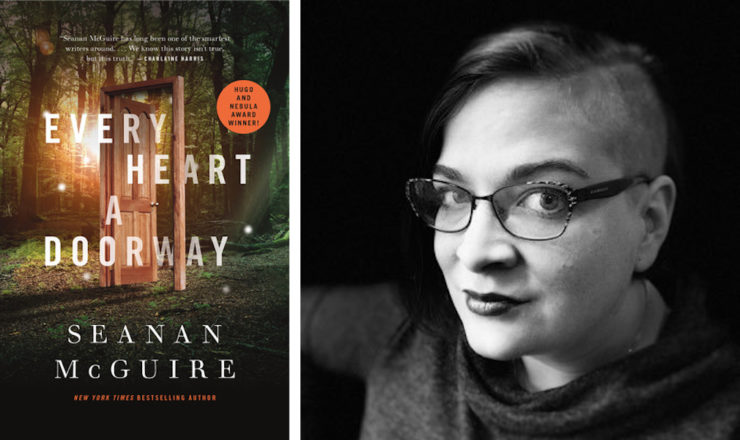

Every Heart a Doorway, a novella by Seanan McGuire, was published in 2016. It tells the story of Nancy, the newest arrival at Eleanor West’s Home for Wayward Children. Nancy isn’t lost. She knows exactly which way she wants to be wards. She just needs to find the magical doorway that will send her back to the fantasy world where she belongs. And at Eleanor West’s school, in this she’s not alone.

I was thirty-three years old, and had made fantasy a craft instead of a lifeline. Nonetheless, reading the book was a sucker punch—a heartfelt, healing sucker punch—to see someone lay it out so clearly. There are plenty of fantasy books that understand isolation, plenty of fantasy books that understand escape, even. But this was the book that stated the tender truth that all queer children and children of doorways learn:

“For us, the places we went were home. We didn’t care if they were good or evil or neutral or what. We cared about the fact that for the first time, we didn’t have to pretend to be something we weren’t. We just got to be. That made all the difference in the world.”

In McGuire’s novella, doorways don’t choose just proper farm boys or girls. Nancy is ace, and there’s Kade, a boy who was exiled from his doorway when the world realized they got a prince instead of a princess. Not every doorway in McGuire’s world keeps you, but every doorway makes you more of who you are.

Buy the Book

The Library of the Unwritten

I’d long ago found my doorway, found my words and my people, and built the world beyond it with my own heart. But if I’d had a book like McGuire’s, a book that bound together all the allusions and fables, and stated plainly what it took to survive…well, I wouldn’t have stopped looking for doorways. That’s not what we do. But I might have known I wasn’t the only one looking.

I was thirty-three years old in 2016, reading the book written for my past self. I was also an aunt, and that was also the year one of my niblings came out as queer. It was no surprise—not to me, at least. We doorway children know each other, don’t we? But even while I celebrated with them, I ached for another queer kid surviving the cornfields.

They have it easier in some ways—of course they do. The cornfields are still there, but there are also doorways, doorways at every turn. They carry a doorway in their pocket, whenever they need it. They have the words, words that are common now, if not always accepted. But that doesn’t make the search easier, or the waiting.

For Christmas, that year, I sent them a copy of Every Heart a Doorway. A copy for them, and a promise. I return to the fields, when I can. They know their queer aunt, and know one doorway, at least, will always stand open. It’s not enough—not nearly enough when the cornfield has closed in around them in the last few years. When doorways get spray painted with swastikas and red hats walk the fields.

I fear for them, of course I do. That’s what adults are supposed to do in these stories. But McGuire’s novella has grown-up doorway children, too. If I’m to be an Eleanor West, an adult that understands, protects, and guides while the young find their own doorways, then my story isn’t over yet. Every Heart a Doorway was a book written for my past self, but it is also written for the future. For all us doorway children, queer kids who grew up.

The doorways aren’t done with us. It’s our turn to tell stories, stories that teach how to find doors, how to open them. It’s our job to hold them open, for as long as we can, for as many children as we can, and promise the doorway is always there. There’s always a door to the land where you can be yourself. Sometimes that door will find you when you’re twelve, sometimes when you’re thirty. But it’ll be there. Doorways are stories, and doorways are hope. You need both to survive in this world, or any other.

Originally published in July 2019.

Amanda is a magpie of plots, bad ideas, and spite. She is a queer speculative fiction writer who writes contemporary fantasy as A. J. Hackwith and sci-fi romance as Ada Harper. Her writing has appeared in Uncanny Magazine and various anthologies, and she’s an alumni of Viable Paradise workshop. Her novel The Library of the Unwritten publishes October 1st with Ace.