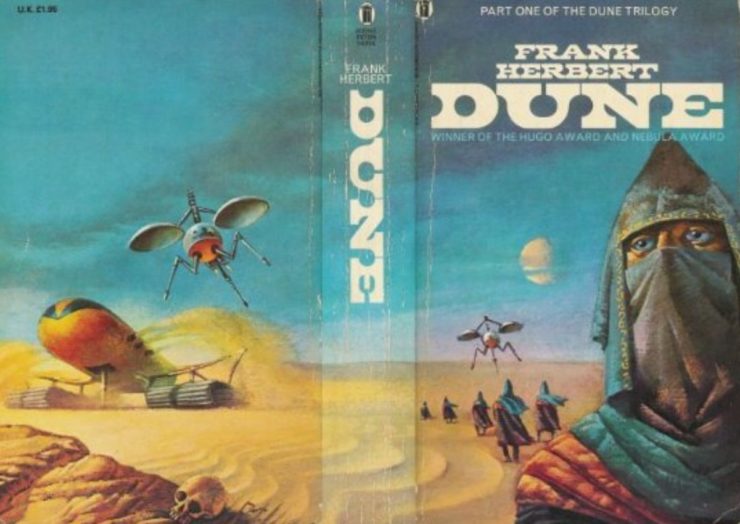

Frank Herbert’s Dune is rightfully considered a classic of science fiction. With its expansive worldbuilding, intricate politics, complex and fascinating characters, remarkably quotable dialogue, and an epic, action-packed story, it’s captured the attention of readers for over half a century. While not the first example of the space opera genre, it’s certainly one of the most well-known space operas, and indeed one of the most grand and operatic. In recent years, the novel is also gearing up for its second big-budget film adaptation, one whose cast and ambitions seem to match the vast, sweeping vistas of Arrakis, the desert planet where the story takes place. It’s safe to say that Dune has fully earned its place as one of the greatest space operas, and one of the greatest science fiction novels, ever written.

Which isn’t bad for a work of epic fantasy, all things considered.

While it might use a lot of the aesthetic and ideas found in science fiction—interstellar travel, automaton assassins, distant planets, ancestral armories of atomic bombs, and, of course, gigantic alien worms—Dune‘s greatest strength, as well as its worst kept secret, is that it’s actually a fantasy novel. From its opening pages, describing a strange religious trial taking place in an ancestral feudal castle, to its triumphant scenes of riding a giant sandworm, to the final moments featuring the deposing of a corrupt emperor and the crowning of a messianic hero, Dune spends its time using science fiction’s tropes and conventions as a sandbox in which to tell a traditional fantasy story outside of its traditional context. In doing so, it created a new way of looking at a genre that—while far from stagnant—tends to focus on relatively similar core themes and concepts, especially in its classic form (though of course there is plenty of creative variation in terms of the science, technology, and settings that characterize classic SF).

Before we dive into the specifics of Dune, we need to define what we mean by “epic fantasy.” Genre, after all, is kind of a nebulous and plastic thing (that’s kind of the point of this article) and definitions can vary from person to person, so it’s important to get everything down in concrete terms. So when I refer to epic fantasy, I’m talking the variety of high (or, if you prefer, “imaginary world”) fantasy where the scale is massive, the heroes are mythic, and the world is so well-realized there are sometimes multiple appendices on language and culture. The kind of story where a hero or heroine, usually some kind of “chosen one,” embarks on a massive globe-spanning adventure full of gods, monsters, dangerous creatures, and strange magics, eventually growing powerful enough to take on the grotesque villains and end the story much better off than where they started. There have been numerous variations on the theme, of course, from deconstructive epics like A Song of Ice and Fire to more “soft power” takes where the main character relies largely on their wits, knowledge of politics, and much more diplomatic means to dispatch their foes (The Goblin Emperor by Katherine Addison and Republic of Thieves by Scott Lynch do this sort of thing incredibly well), but for the purposes of this investigation, I’m going to do what Dune did and stick to the basic archetype.

Dune follows Paul Atreides, the only son of House Atreides, one of several feudal houses in a vast interstellar Empire. Due to some manipulation on his mother’s part, Paul is also possibly in line to become a messianic figure known as the Kwisatz Haderach, a powerful psionic that will hopefully unify and bring peace to the galaxy. Paul’s father Duke Leto is appointed governor of Arrakis, a vast desert planet inhabited by the insular Fremen and gigantic destructive sandworms, and home to deposits of the mysterious Spice Melange, a substance that heightens the psychic powers and perception of whoever uses it—a must for the Empire’s interstellar navigators. But what seems like a prestigious appointment is soon revealed to be a trap engineered by a multi-tiered conspiracy between the villainous House Harkonnen and several other factions within the Empire. Only Paul and his mother Lady Jessica escape alive, stranded in the vast desert outside their former home. From there, Paul must ally himself with the desert-dwelling indigenous population, harness his psychic powers, and eventually lead a rebellion to take back the planet from the Harkonnens (and possibly the Empire as a whole).

It isn’t hard to draw immediate parallels with the fantasy genre: Paul’s parents and the Fremen serve as mentor figures in various political and philosophical disciplines, the sandworms are an excellent stand-in for dragons, everyone lives in gigantic castles, and back in the 1960s, “psionics” was really just an accepted science-fictional stand-in for “magic,” with everything from telepathy to setting fires through telekinesis handwaved away through the quasi-scientific harnessing of “the powers of the mind.” The Empire’s political structure also draws fairly heavily from fantasy, favoring the feudal kingdom-centric approach of fantasy novels over the more common “federation” or “world government” approaches most science fiction tends to favor. Obvious fantasy conventions abound in the plot: the evil baron, a good nobleman who dies tragically, and Paul, the young chosen one, forced to go to ground and learn techniques from a mysterious, mystical tribe in order to survive and exact vengeance on behalf of his family—a vengeance augmented heavily by destiny, esoteric ceremonies, and “psionic” wizardry.

Buy the Book

The Last Emperox

This isn’t a simple palette swap, though. Rather than simply transposing fantasy elements into a universe with spaceships, force shields, and ancestrally held nuclear bombs, Herbert works hard to put them into a specific context in the world, with characters going into explanation of exactly how the more fantastical elements work, something more in line with the science fictional approach. It isn’t perfect, of course, but in doing things like explaining the effects and mutagenic side effects of spice, or by getting into the technical methods by which the Fremen manage to survive in the desert for long periods of time using specially-made stillsuits and other gear, or giving a brief explanation of how a mysterious torture device works, it preserves both the intricate world and also takes the book that extra mile past “space fantasy” and turns it into an odd, but entirely welcome, hybrid of an epic, operatic fantasy and a grand, planetary science fiction novel. The explanations ground the more fantastical moments of sandworm gods, spice rituals, and mysterious prophecies in a much more technical universe, and the more fantastical flourishes (the focus on humans and mechanical devices instead of computers and robots, the widespread psionics, the prominence of sword and knife fights over gunfights) add an unusual flavor to the space-opera universe, with the strengths of both genres shoring each other up in a uniquely satisfying way.

Using those elements to balance and reinforce each other allows Herbert to keep the border between the genres fluid and and makes the world of Dune so distinctive, though the technique has clearly been influential on genre fiction and movies in the decades since the novel was published. Dune is characterized above all else by its odd textures, that critical balance between science fiction and fantasy that never tips over into weird SF or outright space fantasy, the way the narrative’s Tolkienesque attention to history and culture shores up the technical descriptions of how everything works, and the way it allows for a more intricate and complex political structure than most other works in either genre. It’s not quite fully one thing, but not quite fully another, and the synergy makes it a much more interesting, endlessly fascinating work as a whole.

It’s something more authors should learn from, too. While a lot of genres and subgenres have their own tropes and rules (Neil Gaiman did a lovely job of outlining this in fairy tales with his poem “Instructions,” for example), putting those rules in a new context and remembering that the barriers between genres are a lot more permeable than they first seem can revitalize a work. It also allows authors to play with and break those rules, the way Paul’s precognitive powers show him every possible outcome but leave him “trapped by destiny,” as knowing everything that’s going to happen wrecks the concept of free will, or how deposing the Emperor leaves Paul, his friends, and his family bound by the duties of running the Empire with House Atreides forced to make decisions (like arranged marriages) based more on the political moves they have to take than anything they actually desire. In twisting and tweaking the familiar story of the Chosen One and the triumphant happy ending, Herbert drives home the ultimately tragic outcome, with Paul and his allies fighting to be free only to find themselves further ensnared by their success.

All these things—the way Dune merges the psychedelic and mystical with more technical elements, the way it seamlessly settles its more traditional epic fantasy story into a grand space opera concept, and the way it uses the sweeping world design normally found in works of fantasy to create a vaster, richer science fictional universe—are what make it such an enduring novel. By playing with the conceits of genres and inextricably blending them together, Frank Herbert created a book that people are still reading, talking about, and trying to adapt half a century after its release. It’s a strategy more authors should try, and a reminder that great things can happen when writers break with convention and ignore accepted genre distinctions. Dune is not only one of the more unusual and enduring epic fantasies ever to grace the genre of science fiction; it’s a challenge and a way forward for all the speculative fiction that follows it.

Sam Reader is a literary critic and book reviewer currently haunting the northeast United States. Their writing can be found at The Barnes and Noble Science Fiction and Fantasy Book Blog and their personal site, strangelibrary.com. In their spare time, they drink way too much coffee, hoard secondhand books, and try not to upset people too much.

Provided the laws of physics aren’t thrown entirely and blatantly out the window, I’m willing to accept that advanced science (e.g. psionics) may look like magic to me, so it’s still not necessarily fantasy for me at that point.

I picked up Dune in the school library when I was in high school, and Paul’s test with the gom jabar had me hooked. I think the movie attempt in the 80s strayed too far from the book and forgot why it drew readers in. I later saw a retconned version of the movie on TV with a new intro segment with a bunch of exposition on the history/ culture which didn’t improve it. You don’t start the book knowing all the details about the history and culture, but Herbert excelled at feeding them to you bit by bit in a way that never distracted from the story telling.

I also thought the first movie messed up by making the Baron too over the top and outrageous. Here’s hoping the new movie gets things right.

I disagree about the claims regarding genre: the line between soft science fiction and fantasy is a narrow one, but it is very important – Dune is SF.

The book is memorable for a number of reasons, including that its structure is fractal and that it attempts to convey the nature of a prophetic experience by giving the reader information out of sequence and context.

Odd double-posting.

I agree that the Lynch movie failed to capture the book’s spirit – although this may have been in part due to executive meddling. The miniseries did a reasonable job, considering the difficulties of shooting a novel in which the protagonist is supposed to go through puberty in the middle of the story.

I’m still slightly disappointed I read this book so young. One of the first books I ever owned and it’s set a standard that few sci-fi books have managed to meet. I like your revealing the elements that Dune has in common with high fantasy, but I would still very much argue this fits under the sci-fi umbrella, in that the fantastical elements presented are not at all presented at odds with science and the physical world, but as out-workings of highly advanced technological foundations.

Also…thinking of other classic sci-fi – in this case, could we also argue that Foundation fits in the high fantasy mold? A decline of a great empire into barbarism…the few that have wisdom to see the truth set up nuclei for a new and better humanity…ok, never mind, I don’t think I can talk myself into it. Foundation is still sci-fi. =)

The older I get the more I realize that genre is a limiting concept, and that really I like my sci fi with less sci and more characters, I think a lot of science fiction could stand to learn from Fantasy when it comes to how to progress a plot, while fantasy could probably try to be as creative in setting and theme as sci fi tends to be.

Funnily enough though, the earliest sci fi was a lot more like Dune than it was any other kind of science fiction. SF was about kings and epic destiny and prophecy and weird cultures and stuff way before it was about how quantum mechanics can be a metaphor for God or whatever. Dune is essentially just Flash Gordon but given a large amount of literary and creative heft, but it still fits squarely in this older more creative form of sci fi

I think the critical difference is that science fiction is concerned with the logical implications of the weirdness it establishes, while fantasy just permits magic to be incomprehensible.

I finished the book about a month ago. There are no psionics in the first novel, Dune. There is something called the voice which is not psionic. It is a tonal mechanism, not a psychic phenomena. There are also Paul’s shifting visions about the future. That is left to the reader to decide whether the visions are real or not.

I think we’d all get along better if we’d just agree that all of sci-fi is a subset of fantastic (read: fantasy) fiction, and stop worrying about genre classifications so much!

@6/melendwyr: That is a reasonable distinction to draw, but I think that on those merits Dune would stay on the fantasy side. In fiction deemed unambiguously SF, like, say, the aforementioned Foundation, characters’ searches for explanations of the weird phenomena around them are often the entire point of such stories. But in Dune, for the most part the characters don’t seek such answers, and the narrative often does not fill in the gaps.

Perhaps one of the reasons the book is a compelling read, though, is that the narrative is structured such that it can feel as if the text provides more definite answers than are actually there. Most readers probably get the gist of how interplanetary travel is supposed to work, even though such travel is never shown and only discussed in passing. The various powers and abilities associated with the spice and/or the Bene Gesserit—aspects that end up absolutely critical to the story—are foreshadowed by similar, lesser powers that feel sciencey enough to be believable, giving the reader a mental path to believe that the more plot-critical powers are not actually magic (e.g. maybe spice-powered prescience is really just sappho-powered mentat skills turned Up To Eleven). The cumulative effect is like a literary version of a trompe l’oeil painting: the illusion of SF-style expository depth where none actually exists.

(The above only applies when considering Dune on its own; the subsequent books certainly do offer SF-style explanations for some things the first book let slide. But that’s not always desirable: often the spell can be broken by trying to provide definite answers for how the midi-chlorians Heisenberg compensators phlebotinum-powered thingies work.)

Calling magic “psionics” or “the Force” doesn’t make it less magical. The apparently ineradicable need for some people to draw hard boundaries between literary sub-genres is curious.

@7, the Navigators use psionics to visualize where the ship needs to go by scanning the future to find the right path. Paul also has visions of the future after ingesting the Water of Life. The Reverend Mothers have psionic abilities as well, such as being able to communicate with all former Reverend Mothers and neutralize any poison or toxin. All of these are within the first book, though further elaboration comes in later books.

For some reason, I only got around to reading Dune after I had read the Wheel of Time series. Someone mentioned how similar they were, and that I might enjoy it too.

Similar doesn’t describe it well enough. It’s amazing how influential Frank Herbert’s work was to a variety of authors who followed him. As I read, I could see many parallels being drawn between characters and arcs, which only served to increase my enjoyment.

Also, considering our current concerns about global warming and climate change, the story seems even more relevant. When you have a civilization that spans across the universe, yet still relies so heavily on the resources of a single planet, we understand what the author was trying to say.

Sadly, I couldn’t get past the third book. Herbert never could recapture the effortless style of the first, and reading became more and more like a chore to me. Until I finally gave up. I did find out what happens later, so at least there’s some closure.

Still, that first book was incredible. And I can’t wait for the movie coming up soon!

The very point of this blog, and the discussion that follows it, misses the elements that make Dune great.

All the points about Fantasy and SF elements are fair enough. I would not contest any of them. However, none of them matter. Dune is mythology in the classic sense. IMHO, Dune’s most reasonable comparables are not Tolkien or Asimov or whichever other Great Name of contemporary genre fiction you care to name. Dune is alligned far more closely with works like the Tales of Gilgamesh, the New Testament, Greek and Norse Myths and the Bhagavad Ghita.

The reason it defies attempts to classify it is because your labels don’t fit. So don’t bother trying. It doesn’t matter if they fly thopters and spaceships of if they ride sandworms as they breach the shield wall and attack the castle-like fortress. That is just window dressing.

What matters about Dune is the examination of the cult of personality, the use of religion to manipulate people into propelling one person to the pinnacle of society and then how those foundations crumble over time. These are stories of human civilization, themes we see played out over and again through history and in our world today, and any attempt to label them as *this* or *that* is limiting and sad. Who cares if it’s in the SF section of the bookstore, the fantasy section or even the philosophy or literature sections. As long as people can find it…

I’m not sure that I would agree that Dune creates a melange of science fiction and fantasy; I’d rather say that, on a surface level, it hews close to certain aesthetics of epic fantasy, but right beneath that (and actually not hidden at all), it is all sf aesthetics. There’s no magic, and no, there are also no psionics in the dune universe; looking into the future and into parallel realities are strictly understood as functions of the workings of probability and cause and effect; things like Voice also work within the framework of a scientific aesthetic; and most importantly, religion and destiny are solely understood in terms of (collective) psychology. There’s absolutely nothing magical to religion in the Dune universe – quite the contrary, the “Missionaria Protectiva” is a most thorough deconstruction of the “magics” of religion.

This is actually something that makes Dune very different from the many works so clearly inspired by it, from Star Wars to role-playing game settings like Warhammer 40.000 and Fading Suns. Those all take the fantasy aesthetics of Dune and turn them into actual fantasy elements. Dune, in contrast, presents us with something that looks like a fantasy universe, but constantly makes clear that it is everything but.

@alex:

You’re arguing Dune’s themes versus its aesthetics, claiming the latter to be besides the point. However, there’s really no reason to do that. What’s wrong about examining Dune with regards to its fantasy and/or sf aesthetics? Why can’t these aesthetics be a part of what makes it a great novel? Does every article on Dune have to deal exclusively with the themes you outline to be worthwile? Yes, they are certainly elemental to Dune, but there’s no need to limit your examination to them.

@14, of course there are psionic abilities. The Reverend Mothers are able to psychically communicate with all the former Reverend Mothers (in later books, one is even able to talk with Baron Harkonnen); they are also able to convert any poison or toxin inside themselves into something harmless. Paul literally looks into the future to pick the path he wants to follow, as do the Navigators; they aren’t just weighing probabilities, they literally see the future. All of these abilities are granted through ingestion of Spice. Later books introduce more groups that use Spice to obtain abilities above and beyond what his human. There are characters that are capable of controlling the worms with their minds.

@Jakob,

I would contest your aesthetics vs themes supposition. IMHO, the way Dune echoes classical myth and literature is not merely thematic, but also structural; possibly even elemental. It’s like Herbert set out to prove Joseph Campbell’s hypothesis by telling a story that would be universal, only he did it well before Disney and Hollywood turned it into a commercial monster (and incidentally used it to limit creative storytelling). To be clear, I have no evidence that Herbert even read Campbell, but the structure of the story, the literary tools, the characters, the way protagonists and antagonists are depicted, the way good and evil are treated all lean on concepts that are much more universal than SF or Fantasy.

So, to you question: why shouldn’t people debate the SF/Fantasy question about Dune? And on this, obviously I failed to make my point clearly. I apologize for that. IMHO (again), Dune transcends the question itself. Merely to ask the question is to show that you don’t really understand the novel. That is not all that big a deal. Lots of people do and still enjoy the book for a wide range of reasons. But too many writers set out to tell a story and the first thing they do is box themselves in. They define themselves. They think not of the story they want to tell, but rather of the setting they want to exploit. They say “I’m gonna write a space opera” rather than “I’m going to tell a story about a young person’s journey of self discovery as s/he going from youth to national leader.”

Also, to me, this is very Sheldonesque thinking. Humans like to label and categorize things. We like to put them in neat little boxes, and it is almost a cliche that nerd culture would rather debate picayune points like this one than really absorb central truths in art. Again, there is nothing inherently “wrong” with this. If you want to dive in and debate this or that aspect of the novel, or the movie or miniseries or the upcoming Denis Villeneuve film, be my guest.

Perhaps I am being elitist or snobbish, but I find that small and a little sad. It feels very “Orange robe! Purple robe!” to me. I was disappointed to read yet another blog about Dune that rehashed the same kind of shallow nonsense that we’ve all read before. I remember having this very discussion as a teenager in the mid-80’s. That was fine for a bunch of unsophisticated 15-year-old SF/Fantasy nerds. Reading it again yesterday wasn’t nostalgic. It was uninteresting and even a bit irritating. And, as a reader of a blog like this one, I have the ability and the right, to tell the writer I feel he wasted my time and why.

Thanks for engaging with me. I very much appreciate your response. It’s always nice to be challenged on one’s thinking and forced to reexamine your reactions to something. :-)

@BonHed:

Well, all this is never described in terms of psionics. The Reverend Mothers don’t communicate with their predecessors; the access “genetic” memories passed down to them (with the water of life being the catalyst for this process). This might be hocus-pocus, but it is still firmly rooted in the sf aesthetics. And Sheeana in “Heretics od Dune” doesn’t command the worms with her mind; the worms “recognize” her because they retain parts of Leto IIs memories, and therefore spare her and try to communicate with her.

I admit that “Children of Dune” comes pretty close to mixing fantasy and sf with its Leto II superhero shenanigans …

Anyway, I have no issue with reading Dune as fantasy; I’m just saying that it feels wrong to may to say that Dune is mixing sf and fantasy, because it has a very unified aesthetics when it comes to how things are explained; and why I’d say that its more of an sf aesthetic to me, you could certainly argue that the amount of hocuspocus makes it fantasy, however “sfnal” Herbert presents his case.

@alex:

Thanks for your reply; to me, the article doesn’t really seem to try and pigeon-whole the novel (although, as I said, I have other issues with it …). I try to think of genres not as drawers, but as reading protocols that we can apply to texts and see what happens. It’s not arbout arguing whether the Handmaid’s Tale is a mainstream literary or an sf novel; it’s about seeing what happens if we read it in different ways.

Anyway, of course I totally accept that you feel that the article is dealing with one of the least interesting aspects of the novel. I’d even agree to a certain degree – “is it fantasy or sf” certainly doesn’t touch Dune’s core themes. But I can still relate to the question, and I’d say it has a few interesting implications for how the mystical is criticized and deconstruced in the novels.

I would note that Dune and Dune Messiah were serialized in Astounding before they were published as books. Campbell didn’t tend to publish any fantasy. :-)

“Only Paul and his mother Lady Jessica escape alive”

Gurney yHallack says hi.

#15 – I’m not sure that I would agree that Dune creates a melange of science fiction and fantasy

I see what you did there.

The technology of the Dune universe is presented as based on scientifically-understood principles that are simply beyond our current knowledge. So is the, for lack of a better term, ‘psionics’. It’s even pointed out that the “Ancients”, meaning us, investigated certain branches of knowledge that were lost in the destruction of Earth… and were probably the ones responsible for the creation of the sandworms.

So it’s not fantasy, it’s science fiction, if admittedly of a very soft bent. The actual speculation concerns itself more with sociology, psychology, and applied religion than physics… although Herbert well knew that the distinction is somewhat artificial. The Guild specializes in almost pure mathematics… and is the only faction capable of piloting ships through foldspace as a consequence.

That Dune draws on tropes from mythology, legend and fantasy is obvious. Whether that means it’s “actually” a fantasy novel (and not a science fiction novel?) is much more dubious.

My personal definition of science fiction is fiction that engages with the hypothetical implications of science or technology. Which Dune definitely does. (With its future setting, space travel and laser guns, it trivially fulfils more superficial definitions.) The original inspiration for the book was a project to stop the spread of sand dunes on the Oregon coast by planting certain types of grass. Frank Herbert extrapolated from this the idea of a project to turn a whole planet from desert to vegetation using natural processes: ecological engineering. That’s as pure a science fiction concept as you can get!

It is also very concerned with how societies and individuals are conditioned by technology, from the Fremen stillsuits and the shield-dependency of the Empire to the lack of computers and subsequent development of mental disciplines.

The universe in Dune reflects a bunch of ideas from social science, history and psychology (sometimes magnified beyond the realistic, but that’s the prerogative of fiction). Some of its observations are pretty much the epitome of what soft science fiction is all about. (“Pausing in the doorway to inspect the arrangements, the Duke thought about

the poison-snooper and what it signified in his society. All of a pattern, he thought. You can plumb us by our language—the precise and delicate delineations for ways to administer treacherous death. Will someone try chaumurky tonight—poison in the drink? Or will it be chaumas—poison in the food?“)

As for the “psionics,” I think there are two important points to be made. (1) While scientifically dubious (not to say nonsense) and arguably close to magic, this sort of thing has always been accepted in the sci-fi genre, from Foundation to Babylon 5 — in large part because John W. Campbell was fascinated by it. (2) Frank Herbert was writing in the sixties, at a time of high interest in exploring “higher states of awareness.” He appears to some extent to have believed in, or at least have had an open mind towards, the existence of such phenomena and that they would one day be within the reach of science.

Therefore, I would argue that Dune is at its core a science fiction novel, with some fantasy genre trappings, rather than the other way around.

What if we exclude prescience, and the mental abilities linked to the spice, from our analysis? Those things require alternate physics. What if we merely look at the mental and physical training possessed by various characters before the story shifts to Arrakis?

Clearly it’s science fiction, even though such conditioning is far beyond what current science understands.

@@.-@ I also encountered Dune at too young an age, and didn’t care for it at all. A bit too strange for a boy used to the logical and science-based stories I usually read in Analog.

@20 Actually, Campbell published a fair amount of what you might call “rigorous” fantasy in Analog. The Lord Darcy stories, which appeared at about the same time as Dune, were set in an alternate history where magic was real. And Campbell had a soft spot for the paranormal, which in my mind falls into the realm of fantasy, even if it is called the “science” of psionics.

In the mid-sixties, the first SF magazine I subscribed to was Analogue. The first issue I got featured Dune, starting in the middle. There was a brief synopsis of an earlier chapter. It only confused me.

It started with somebody was holding a knife on somebody, saying, “If you use the Voice I will kill you by reflex.” I didn’t know what was going on. But I soon got into the story.

Later I heard Herbert give a speech. He said the science he was exploring in Dune was ecology.

I’m always surprised that few people draw a comparison between Dune (1965) and Lawrence of Arabia as depicted in the David Lean film (1962).

A white man in the desert plots with a desert people against foreign rulers in the city… there’s even a sand worm in Lawrence of Arabia… but we recognise it as an attack upon a train. Not forgetting the valuable resource required by a large empire the locals could control… if only they could take control.

But the story is in the details and the Lawrence tale is very different from Paul’s.

@28

There’s also the fact that Lawrence of Arabia is a (mostly) true story. His exploits were well known decades before Dune was written.

Truly great story by any definition! Hopeful that the new vision behind upcoming movie will capture most of this. Direction,score,writing,all come together for a truly epic film version of a truly epic novel. P.S. Hans Zimmer gets super siren Lisa Gerrard to call forth Shai Hulud!!!…..BINGO!